Since 2016, Kristopher K. Townsend has been the webmaster and editor of this site, Discovering Lewis & Clark®. He has been actively photo-documenting the Lewis and Clark Trail since 1995. He attempts as closely as possible to re-create scenes as described in the journals including the same time of year, natural state, location, and weather. He has contributed numerous photos throughout the Discovering Lewis & Clark website.

Kris taught several years as a tenured instructor at Spokane Falls Community College. His courses included Internet programming and other information technology and computer science courses. During that time, he was also the series editor and an author of a popular college textbook series on Office Technology.

Shortly after the advent of the World Wide Web, he managed a web server featuring digital photos, digital video, and articles created by his Glenwood Heights Primary students. Topics included historical sites of Clark County (Washington State), wildflowers and birds of Clark County, and how-to videos for school’s physical education program.

Contributions

Making Pemmican

by Kristopher K. Townsend

This staple Indian food was adopted by northern explorer Alexander Mackenzie, Lewis and Clark, and the North American fur trade. This article explains how it was made, why it worked well for travelers, and how it was made and eaten. Recipe included.

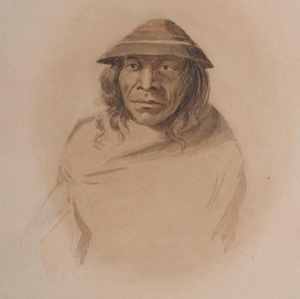

The Tillamooks

by Kristopher K. Townsend

The Tillamook Indians, cordial hosts and friends to the visiting Americans in 1806, may have numbered about 2,200 persons at that time.

The Shawnees

by Kristopher K. Townsend

As soon as the expedition boats arrived at the Mississippi River, the captains began counting Shawnee people. The Estimate of the Eastern Indians reports that 600 “Shawonies” were living on the “apple River near Cape Gerardeau.”

The Kathlamets

by Kristopher K. Townsend

The expedition journalists recorded several encounters with the Kathlamets, or Cathlamets, during their stay at the Pacific coast during the 1805–06 winter. On 11 November 1805, while hunkered down in a “dismal nitch” on the north side of the Columbia, a canoe “loaded with fish of Salmon Spes. Called Red Charr” pulled to shore. After buying 13 sockeye, Clark marveled.

Wild Cherries

by Kristopher K. Townsend

As the expedition moved across the Northern American continent, Lewis took particular notice of the changes he saw in the wild cherries. For a deeper dive into the Lewis and Clark Expedition’s encounters with wild cherries, see these four articles.

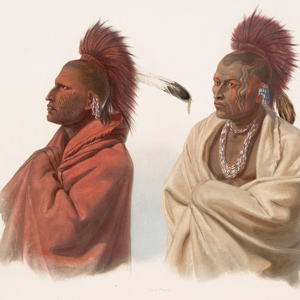

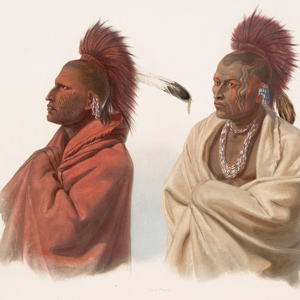

The Sauks and Foxes

by Kristopher K. Townsend

To outsiders in 1803, the Sauk and Fox people living on the Mississippi River in Illinois, Iowa, and Wisconsin were seen as one people. Both peoples spoke the Sauk-Fox-Kickapoo dialect of Algonquian and had similar cultures and economies.

The common sunflower as a staple food among the Mandans and Lemhi Shoshones did not escape the attention of the journalists. Includes two traditional Hidatsa recipes.

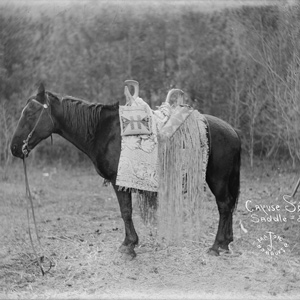

The Cayuses

by Kristopher K. Townsend

Clark’s name for the Cayuse, the Ye-E-al-po Nation, may have been his phonetic spelling of the Nez Perce name for them—Waiilatpu. The people are noted for their namesake horses and the 1847 murders at the Whitman Mission.

The Lower Chehalis

by Kristopher K. Townsend

The Lewis and Clark Expedition encountered the Lower Chehalis mainly during their stay at Station Camp on Baker Bay. In the journals, the people’s name is spelled Chieltz and Chiltch.

The Otoes and Missourias

by Kristopher K. Townsend

At the time of the expedition, the nation from which the Missouri River derived its name were so reduced by smallpox and attacks that they had abandoned their villages and merged with other tribes—Kansas, Osages, but primarily, the Otoes.

Two widely separated branches of Salishan languages developed prior to 1800, Coastal and Interior. Lewis and Clark encountered several nations from both of these branches.

The Clatsops

by Kristopher K. Townsend

The creek where Coyote built his legendary house—today’s Neacoxie Creek—flows north to south bisecting nearly the length of the Clatsop Plain. A village at the estuary created by the ocean, Neacoxie Creek and the larger Necanicum River is Ne-ah-coxie Village. Nearby were three other Clatsop villages, and for a short time, a salt works built by soldiers from the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

Everybody liked the abundant serviceberry fruit—the Lemhi Shoshones were living on them, the enlisted men “regaled themselves,” and Lewis was the first to collect a specimen for science.

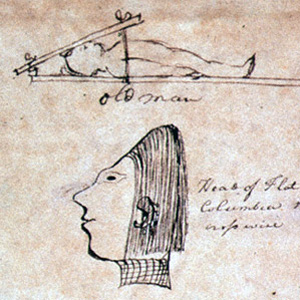

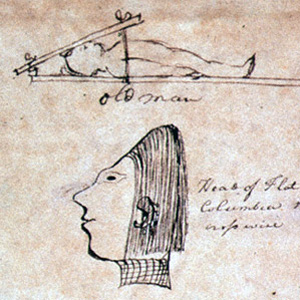

The most remarkable trait in the Clatsop Indian physiognomy, Lewis wrote on 19 March 1806, was the flatness and width of their foreheads, which they artificially created by compressing the heads of their infants, particularly girls, between two boards.

Before signing off in his last journal entry, Lewis had to botanize one last time. He concludes with an accurate description of the pin cherry, Prunus pensylvanica.

Lewis collected a specimen of bitter cherry, Prunus emarginata, while at Long Camp on 29 May 1806 and described it on 7 June 1806. He wrote that “the natives count it a good fruit”.

The Blackfeet

by Kristopher K. Townsend

They commonly called themselves saokí•tap•ksi meaning ‘prairie people.’ The meaning ‘people with black feet’ comes from exonymns—the names given by other, external tribes. Historically, several related groups comprise the Blackfoot or Blackfeet people.

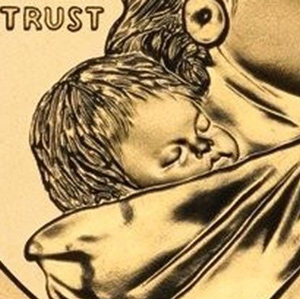

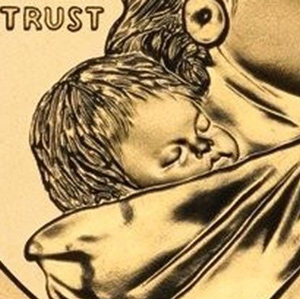

Jean Baptiste in Europe

by Kristopher K. Townsend

Jean Baptiste’s European experiences with Duke Paul of Württemberg were the capstone of an education that started in a Hidatsa village and developed in St. Louis under the sponsorship of William Clark.

Whether they be boatmen, interpreters, traders, privates in the U.S. Army, diplomats, or cultural guides, the contribution of the French men already living in the Illinois and Louisiana region was “mission critical.”

The Yankton Sioux

by Kristopher K. Townsend

The Yankton along with the Yanktonai make up the Western Dakota division of the Dakota People. Although the Yankton and Yanktonai sometimes considered themselves to be one people, their separate locations resulted in a unique history for each.

The Poncas

by Kristopher K. Townsend

On 5 September 1804, the captains sent John Shields and George Gibson to the Ponca villages. The privates reported that the people were away hunting buffalo and that they had not planted their gardens.

The Arikaras

by Kristopher K. Townsend

Spelled variously in the expedition journals, Clark sometimes called the Arikara people Pawnee due to their similar linguistic origins—both were Caddoan-speaking people. Weakened by smallpox and Sioux attacks, they would have significant impact on American fur trade interests on the Upper Missouri and affect the lives of several expedition members.

The Wahkiakums

by Kristopher K. Townsend

The Wahkiakums exemplify the complexities encountered when trying to classify Chinookan peoples. Linguistically, they spoke the Upper Chinookan Clackamas dialect. Culturally, they were related to the Lower Chinookan Clatsops and Chinooks proper. They resided primarily along the north side of the Columbia between Grays Bay and Cathlamet, Washington.

The Kansas

by Kristopher K. Townsend

Known in the journals as Kanzas, Kansas, Kansias, Kansies, Kar sea, and Kah they are popularly called the ‘People of the South Wind’. At the mouth of the Kansas River, the captains ordered a defensive wall built, but no Kansa warriors appeared.

Jean Baptiste in California

by Kristopher K. Townsend

After a brief service as Alcalde of San Luis Rey, Jean Baptiste moved to the gold fields around Auburn, California where he lived for 19 years.

The Hidatsas

by Kristopher K. Townsend

Prior to the expedition, the Hidatsa had settled in three villages just north of two Mandan villages in a complex now called the Knife River Villages. There, they practiced horticulture and hunting in the manner of the Plains Village tradition.

The Potawatomis

by Kristopher K. Townsend

By 1800, the Potawatomi had successful traded with the French to the north and the Spanish in St. Louis. They resided in a large region surrounding the southern half of Lake Michigan between the Mississippi River and Lake Erie and extending south to the mouth of the Illinois River.

The Lenape Delawares

by Kristopher K. Townsend

About 1784, a small group of Shawnee and Delaware migrated from Illinois to southeastern Missouri. Ten years later, the Spanish encouraged members in Illinois to migrate the Cape Girardeau area as a way to protect their own settlements from the Osage.

The day Sacagawea gathered Indian breadroot, Lewis wrote a detailed ethnobotanical description. The specimen he prepared a year prior is now used as the primary identifier of the species.

This variety of the common chokecherry gave Lewis his decoction of simples and was the subject of his botanical scrutiny.

The Skilloots

by Kristopher K. Townsend

The Skilloot were an Upper Chinookan group that spoke the Clackamas dialect of the Chinookan language. They were located on both sides of the Columbia River above and below the mouth of the Cowlitz. At first, the captains applied the name over a much wider area, perhaps misinterpreting a similar expression meaning ‘look at him!’. Cape Horn, a few miles east of Washougal, was named sqúlips, and could be the origin of the tribe’s name.

Jean Baptiste, Mountain Man

by Kristopher K. Townsend

Jean Baptiste’s 17-year career as a mountain man comes from a scattering of writings from some of the most notable trappers of the era.

Lewis collected buffaloberry specimens which were new to science and Clark had them in a delightful tart. Native Americans had been eating the bright red berries for generations.

Lewis’s Suet Dumplings

by Kristopher K. Townsend

When making suet dumplings during the portage around the falls of the Missouri, Lewis demonstrated a unique and magnanimous act of leadership. This article includes a recipe.

Justified by the ethnobotanical record, the captains went to unusual lengths to preserve and document echinacea. Most—if not all—the Tribal Nations encountered along the Missouri River used the plant to treat snakebites in the manner described by the two captains.

Jean Baptiste Charbonneau

by Kristopher K. Townsend

This 9-page series examines the life of Jean Baptiste Charbonneau—the infant son of Sacagawea who traveled across the continent with the Lewis and Clark Expedition. He was educated in St. Louis and Europe, a mountain man, military guide, and California miner.

Jean Baptiste Charbonneau’s education began in a Hidatsa village. In St. Louis at the age of five or six, his classical education began under the guardianship of William Clark.

The Osage were experienced traders, exchanging horses and Indian slaves for French guns, knives, axes, kettles, and other metal objects. After the 1760s, the Osage adopted a new economic system of planting gardens in permanent villages, summer hunts in the plains, and fur-trapping in the winter.

The Iowas

by Kristopher K. Townsend

Iowa culture blended lifeways and customs of their neighbors: Horticulture and a well-defined, patrilineal class system was learned from the Sioux, a clan system was adapted from Algonquian-speaking neighbors, and like the Plains culture, they practiced the summer village method of hunting the American bison.

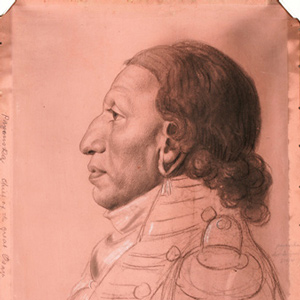

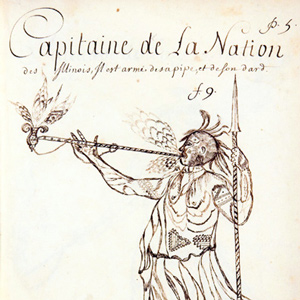

The Illinois Tribes

by Kristopher K. Townsend

The expedition set up camp near a town named after the Cahokia, one the Illinois tribes. The captains reported that Missourias, the Illinois, Cahokias, Kaskaskias, and Piorias were nearly destroyed by the Sauks and Foxes.

The Assiniboines

by Kristopher K. Townsend

The Assiniboines were nomadic hunter-gatherers roaming primarily along the rivers in Saskatchewan and western Manitoba. They often dropped south into present-day Montana and North Dakota, especially in their role as middle-men between the English trading companies and the Hidatsas to the south.

Siouan Peoples

by Kristopher K. Townsend

On 31 August 1804, Clark, frustrated in his attempt to draw a clear picture of the Sioux, summarized what he did know. “This Nation is Divided into 20 Tribes possessing Seperate interests . . . .”

The Cheyennes

by Kristopher K. Townsend

Many, including the expedition members, misheard the people’s name as ‘chien’—French for ‘dog’. Their name actually comes from the Sioux exonym shahíyena, perhaps meaning ‘people of alien speech’. The captains thought that they might make good trading partners.

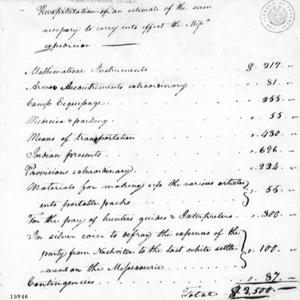

Lewis’s Estimate of Expenses

by Kristopher K. Townsend

Prior to Jefferson’s annual message to Congress on 15 December 1802, Lewis prepared a roughly itemized estimate of $2500 as the cost of the expedition.

The Lakotas

by Kristopher K. Townsend

Presently known as the Lakota people, Lewis and Clark most often called them the Tetons. There were three main groups: Oglala, Brule, and Saone. The bands typically lived separately, hunted freely within each other’s territory, and came together for community events.

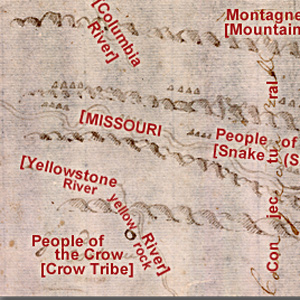

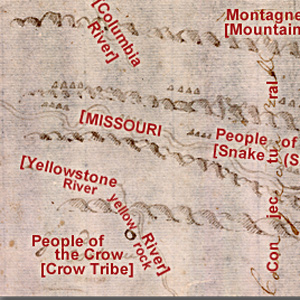

The Mountain Crow and Awatixa Hidatsa share a common ancestry as do the River Crow with the Hidatsa proper. During the expedition, no one would see any Crow people, but those people certainly noticed the expedition passing through stealing all the horses Clark had with him.

The Clackamases

by Kristopher K. Townsend

The Clackamas people had about twelve villages south of the Columbia River, along the Clackamas River, and at Willamette Falls in what is now Portland and Oregon City. They spoke the Clackamas dialect as did nearby Multnomahs and Skilloots. On 2 April 1806, two young Clackamas men came to “Provision Camp” near present-day Washougal and sketched a map of the Willamette River, the mouth of which the expedition captains had failed to find.

The Omahas

by Kristopher K. Townsend

The captains appeared eager to meet with the Omaha. They tried to find them at their two biggest villages and planted a flag at the gravesite of the chief who for many years had controlled trade in the region, the infamous Blackbird.

As they traveled up the Missouri in the summer of 1804, the journalists took note of a wild cherry different than the wild cherry of their homes. It was the common chokecherry, which grew on bushes instead of trees.

The Mandans

by Kristopher K. Townsend

After the 1781 smallpox epidemic, the Mandan had moved into to a more defensible position in two villages immediately south of the Hidatsa at the Knife River. The Mandan-Hidatsa alliance had developed many years prior, and the two tribes previously shared their large hunting territory to the west.

Perhaps he was seeking new gold fields, maybe California was getting too crowded, or maybe he simply wanted to see the mountains and prairies of his mountain man days. After a long life, the journey would be his last.

La Vérendrye’s 1728 name for Spirit Mound contains several puzzling statements. Pako’s reference to that “very fine gold-coloured sand,” suggests the “little mountain” was located in a fabulous land, an Eldorado, of precious natural riches.

What did the captains mean when they say they stopped to jerk their meat? At the time of the expedition “jerk” simply stood for “dried meat.” This article includes a recipe.

As a military guide in the U.S.-Mexican War, Jean Baptiste and the Mormon Battalion were involved in a defining moment in the American Southwest.

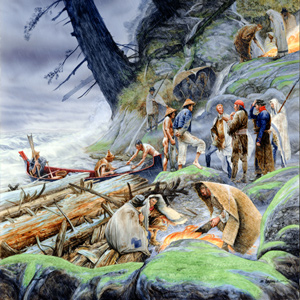

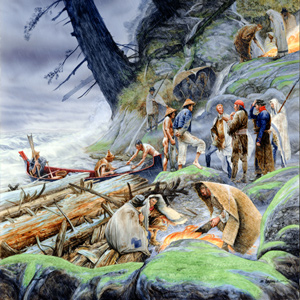

The Watlalas

by Kristopher K. Townsend

Watlala was the name of a key Upper Chinookan village at the Cascades of the Columbia. The name has been extended by many to mean the tribe more often called the Cascades. The captains called them the Shahala, meaning ‘those upriver.’ The natural constriction of the river provided the people with a fishery and a good measure of control over those who traveled up and down the river. As a result, the Cascade Clahclellah village which the expedition visited on 31 October 1805 and 9 April 1806 was a major trade center before and during white contact.

Making Candles

by Kristopher K. Townsend

Early in 1806 while wintering at Fort Clatsop, the last candles burned down, and Lewis described how they would make new candles out of tallow rendered from elk fat. This is the process.

One of the tasks assigned to the expedition was to replace the French, Spanish, and English peace medals previously gifted to North American Indians with those from the United States. The gifts symbolized mutual loyalty in trade and, at least to the Indians, military protection.

The Multnomahs

by Kristopher K. Townsend

When interviewing William Clark and George Shannon to prepare his condensation of the expedition journals, Nicholas Biddle wrote in his notes that “The Multnomah nation is placed on the Wappatoe Island opposite the mouth of the Multh. river and the inlet which forms the island. . . . the neighbors speak of the Multnomah nations as great &c.”

Wind Mountain was at the western extent of a series of Upper Chinookan villages called by Lewis and Clark the “Chilluckkittequaw nation.” Apparently, when asked for a tribal name, the captains were given the word for ‘he pointed at me’. Chilluckittequaw was adopted as their name a century later by early ethnographer Frederick Hodge. Between Wind Mountain and Hood River, nine villages have been identified, some overlapping with Klickitats

The Atsinas

by Kristopher K. Townsend

Today, they are called the Atsina or Gros Ventre, but their names in the historical literature—Big Bellies, Gros Ventre and Minnetares—cause confusion even to this day. The expedition never met them, but their presence affected the expedition in several ways.

Perhaps more than any North American people, the Kickapoo exemplify the transitory nature of the native nations encountered during the Lewis and Clark Expedition. In 1803, there was at least one village near Ste. Genevieve on the Mississippi River.

The Chinooks

by Kristopher K. Townsend

Today, Chinook often refers to the politically united Lower Chinook, Clatsops, Willapas, Wahkiakums, and Kathlamets. To Lewis and Clark, the Chinook were the people living on the north side of the Columbia River’s estuary. When Lewis and Clark met them, the people of Baker Bay had been trading with European ships for more than a decade.

The Nez Perce

by Kristopher K. Townsend

First encountered September 1805 when John Colter met them on Lolo Creek near Travelers’ Rest, they would remain with the expedition in one way or another until 25 October 1805 saying their goodbyes at Rock Fort at The Dalles of the Columbia River. They were together again between 23 April 1806 and 4 July 1806, the expedition’s longest period of contact with any Native American Nation.

John Evans provided maps of the Missouri River and Rocky Mountains, the most significant outcome of the Mackay-Evans Expedition.

The captains’ journals give us a small glimpse into the experiences of Jean Baptiste Charbonneau as he traveled with the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

The French explorer Samuel de Champlain found the vegetable growing in Indian gardens along the Saint Lawrence seaway and carried specimens of it back to France in 1603, where its root soon became a staple food for humans.

François Saucier

by Kristopher K. TownsendFrançois Saucier established a settlement at Portage des Sioux, a strategic part of the St. Charles district.

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.