On this day with Lewis & Clark

December 11, 1803

St. Louis fanfare

From Cahokia, Clark takes the boats across the Mississippi and arrives in St. Louis under full sails and colors. Many people come to the landing to greet them.

December 11, 1804

Sun dogs

At Fort Mandan below the Knife River Villages, rings appear around the sun when its light hits ice crystals suspended in the air. Due to the cold, Clark orders all the hunters to return to the fort.

December 11, 1805

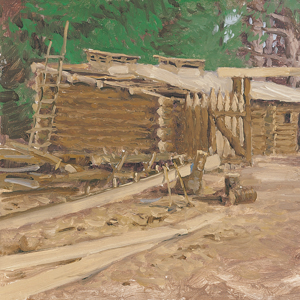

Putting up huts

At the Fort Clatsop construction site on the present Lewis and Clark River, rains are constant as the men put up the huts. Several of the enlisted men are sick or injured.

Up the Mississippi

14 November—11 December 1803

On 20 November 1803—after the expedition encamps nearly a week at the mouth of the Ohio—the barge and boats are moved against the Mississippi current.

The crews work their way to Fort Kaskaskia—recently constructed in the Illinois Territory to support the transfer of the Louisiana Territory—ceded to France on 30 November yet still controlled by Spain. At Kaskaskia, the captains recruit twelve soldiers. They are also told that Spain will not allow them to continue up the Missouri until at least the next spring.

In early December, Lewis negotiates winter arrangements with the Spanish governor in St. Louis. Then, on 11 December, Clark arrives with the boats displaying full sails and colors. The American soldiers could visit the city, but the expedition would not be able to build winter quarters there.

Day-by-Day Pages In-depth Articles

Winter at Fort Mandan

26 October 1804–6 April 1805

On 2 November 1804 below the Knife River Villages, work begins on the expedition’s winter fortification. The men’s quarters, storage rooms, and the 16-foot pickets, are designed for defense against hostile Indians, especially the Sioux, who would be quite troublesome, although they never attacked the fort directly. “This place we have named Fort Mandan,” Lewis recorded, “in honour of our Neighbours”—their kind and congenial Mandan Indians. Here they celebrate their second Christmas and New Year’s Day.

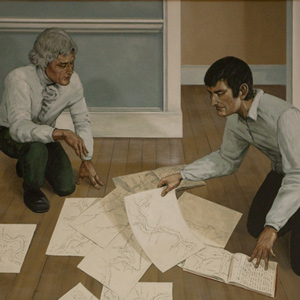

On 28 February 1805, sixteen enlisted men are assigned to hew six canoes from cottonwood logs, and they finish them in 22 days. Meanwhile, the rest of the men make rope, leather clothing and moccasins, cured meat, and battle axes to trade for corn. Lewis prepares botanical, zoological, and mineralogical specimens for shipping back to President Jefferson. Clark works on his Fort Mandan maps.

By the time they are ready to leave Fort Mandan, they add some key members to the permanent party: Toussaint Charbonneau, his wife and infant son—Sacagawea and Jean Baptiste, and French trader Jean-Baptiste Lepage. Each would play critical roles in the expedition’s journey to the Pacific Ocean.

Day-by-Day Pages In-depth Articles

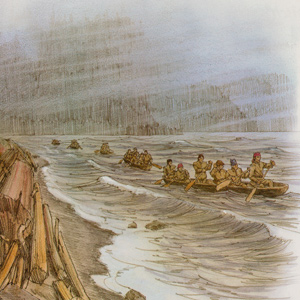

Winter at Fort Clatsop

7 December 1805–22 March 1806

The expedition leaves Tongue Point on 7 December 1805, and immediately upon their arrival at a small point of land above the Netul River, begin to construct winter quarters. They would name it Fort Clatsop in honor of their neighbors.

The weather is sometimes snowy, sometimes icy, but almost always rainy. Their diet is typically elk, which quickly spoils in the warm, wet climate. Visiting Clatsops and Kathlamets sell them sturgeon, wapato, and eulachon as well as woven mats, bags, and waterproof conical hats.

A saltworks near present Seaside, Oregon is established to make salt by boiling seawater. In early January, Clark visits the salt works on his way to get blubber from a beached whale. Sacagawea, who hadn’t yet seen the ocean, insists she be included in his group.

After the dark and damp coastal winter and nearly two years since leaving St. Louis, everyone is anxious to head back.

Day-by-Day Pages In-depth Articles

Featured Members

Hugh Hall

Private

As if to confirm the captains’ poor evaluation of the new arrivals from Fort Southwest Point, a scant nine days after his arrival, Hall was among a group of six or seven men who got drunk on New Year’s Eve.

Thomas Howard

Private

On 23 January 1806, Lewis dispatched Howard and Werner to the Salt Camp on the ocean beach, to bring back a supply of salt. When they had not returned by the 26th, Lewis feared they had gotten lost.

John Shields

Private

During the damp winter at Fort Clatsop and throughout 1806, the journals speak more and more often about Shields’ life-sustaining work as gunsmith. Certainly the guns had seen hard use.

Quick Links

Meriwether Lewis William Clark Sacagawea York Jean Baptiste Charbonneau Seaman All Members

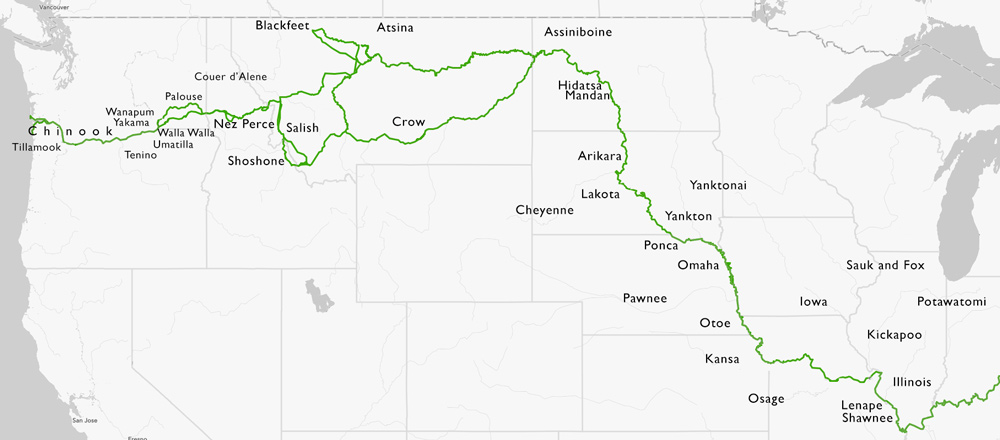

Native Nations Encountered

Northwest Coast

Plateau / Southwest

Northeast

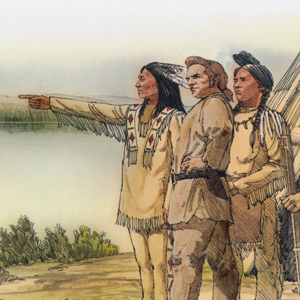

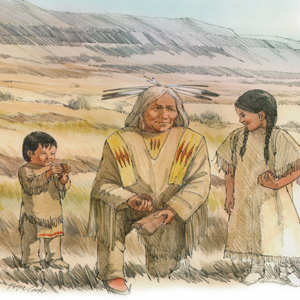

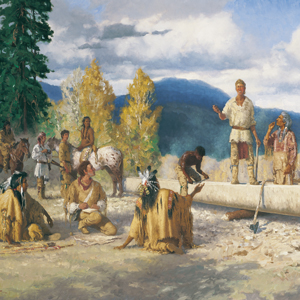

Featured Artist Roger Cooke

The Yakima River

The Dismal Nitches

First Salmon Ceremony

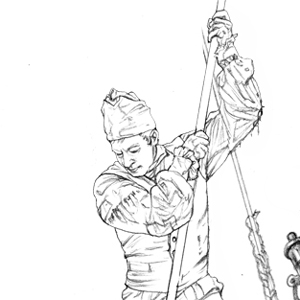

Historical artist Roger Cooke worked with the Washington State Historical Society to recreate several Lewis and Clark scenes of their trek in Washington and Oregon. His art is featured on many interpretive signs at waysides throughout this area of the historic trail. Cooke’s works bring people to the forefront of the Lewis and Clark story. His illustrations feature not just the expedition members but Nez Perce, Palouse, Yakama, Wanapum, Walla Walla, Umatilla, Tenino, Wishram, and various Upper and Lower Chinook Peoples. He displays a full spectrum of emotions—even smiling Indians!—and multi-generational families near their villages. These are stories that modern cameras and digital editing cannot capture.

More

The Fur Trade

Given President Jefferson’s directive to establish commerce, the captains worked extensively within a long-established network of North American fur trade. Part of their mission was to help establish the United States of America’s position within that industry.

Other Topics

Other topics include music, holidays, High Potential Historic Sites, and an index of articles from We Proceeded On.

Synopsis of the Expedition

by Harry W. FritzCalendar

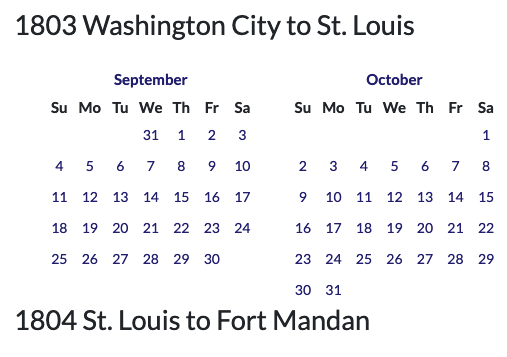

Expedition Calendar

Links to every day-by-day page in a calendar format spanning 31 August 1803 to 26 September 1806. A page every day!

The Arts

Because of the literate journalists, historians and visual artists can tell the Expedition’s story. When they celebrated with song and dance, we too can share in the experience.

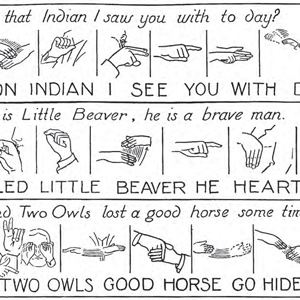

Language

From clichés and colorful sayings of the time to Native American languages, these pages feature the art of language.

Medicine on the Trail

From major crisis such as the death of Sgt. Floyd, Lewis’s gunshot wound, and the illness of Sacagawea to minor events such as sexually transmitted diseases, mosquito-born illnesses, and deep cuts, the medical aspects of the Lewis and Clark Expedition provide an interesting topic of study.

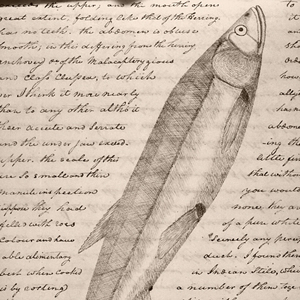

Hunting and Fishing

Although hunting and fishing were often considered a ‘gentleman’s sport’ especially in Europe, hunting and fishing for Native Americans and Americans alike were a matter of survival. The success of the Lewis and Clark Expedition depended on the success of its hunters.

Related Explorers

Lewis and Clark were among several significant explorers of North America both before and after the expedition.

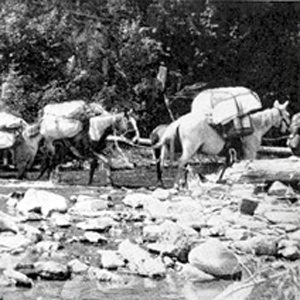

Horse Travel

To cross the Rocky Mountains, the Lewis and Clark Expedition needed horses and the skills to manage them. Despite their seemingly constant struggle to find missing and stolen horses, as a kind of calvary unit, they left hoof prints on approximately 1,500 miles of western terrain.

Native American Nations

The Lewis and Clark Expedition benefited from the Indians’ knowledge and support. Maps, route information, food, horses, open-handed friendship—all gave the Corps of Discovery the edge that spelled the difference between success and failure.

A Military Corps

Throughout the expedition the soldiers were expected to conform to the rules and routines of the frontier soldier of 1803.

Trail Diplomacy

Lewis and Clark left behind among many Indians a legacy of nonviolent contact. Those who came later enjoyed that legacy and too often betrayed it.

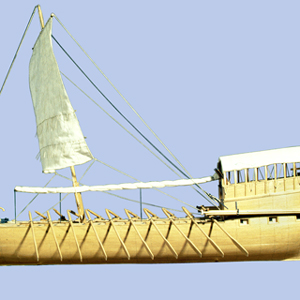

The Boats

Starting at Pittsburgh, traveling to the Pacific Ocean, and then returning to St. Louis, the Lewis and Clark Expedition traveled approximately 10,600 miles. Of that, 85%—over 9,000 miles—was by boat. To understand travel in the early 1800 American West is to understand the boats and challenges of river navigation.

People

The success of the Lewis and Clark Expedition was due to its many members and the people they met, including politicians, Eastern gentleman scientists, traders, and the many people already living in the American west.

Expedition Members

Scientific Explorations

Their work in the emerging fields of botany, ethnography, geography, geology, and zoology are now considered classics of early American scientific literature.

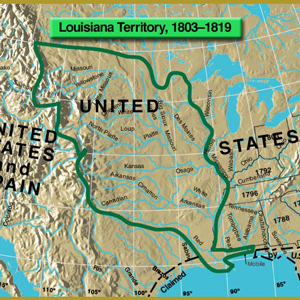

Louisiana’s Purchase

The President’s representatives in Paris had bargained successfully with Napoleon’s bureaucrats not only to buy the port of New Orleans, then the keystone of the continent, but also to acquire, at three cents an acre, an area extending from the Mississippi River to . . . where? No one knew until Meriwether Lewis stood at the crest of the Rocky Mountains at a place known today as Lemhi Pass, on 12 August 1805.

Legacies

Legacy is a very slippery sort of term. If we could erase our myth concepts of Lewis and Clark … it might reawaken something really extraordinary in our national consciousness.

The Trail

Starting with its genesis in Jefferson’s Monticello, Lewis’s training and preparations in Philadelphia, and the barge’s excursion down the Ohio River, the route they took, often called the Lewis and Clark Trail, crosses the continent weaving an epic tale of western exploration treasured by many today.

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.