Worthy of Notice

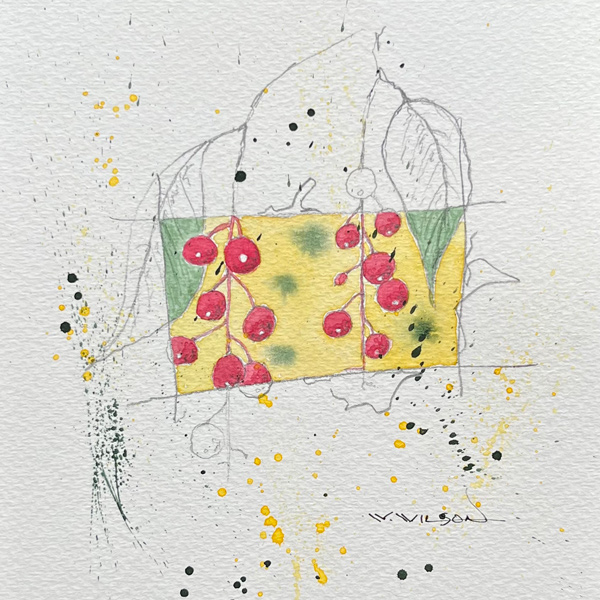

Black Chokecherry Leaves and Raceme

Prunus virginiana, var melanocarpa

© 2011Thayne Tuason. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Lewis begins his journal entry of 29 May 1806 with “No movement of the party today worthy of notice.” Pvt. William Bratton, toddler Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, and an old Nez Perce chief are recovering from various ailments. Unknown to Lewis, Pvt. Robert Frazer is trading an old razor for two Spanish mill dollars at a Nez Perce salmon fishing camp on the Snake River.[1]See Frazer’s Razor and Ordway’s Salmon Fishing Trip. As for himself, Lewis was far from idle. He wrote about the short-horned lizard and added four plants to his collection: cascara buckthorn, Frangula purshiana; creambush oceanspray, Holodiscus discolor; bitter cherry, Prunus emarginata; and black chokecherry, Prunus virginiana var. melanocarpa. All these were new to science and certainly worthy of notice.

The day at Long Camp wasn’t Lewis’s first encounter with the black chokecherry, Prunus virginiana, var melanocarpa, which grows in Montana, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington.[2]U.S. Department of Agriculture, “PLANTS Database,” plants.usda.gov/home/plantProfile?symbol=PREM, accessed 18 March 2023. Waiting for snow to melt at Long Camp provided his first opportunity to observe the plant’s spring blossoms, and his description of the racemes being “from 4 to 5 inches in length” defines the only variety of P. virginiana that grows along Idaho’s Clearwater River. The two wild cherry specimens collected on this day are harder to identify. The two surviving specimens from Lewis’s plant collection—most likely bitter cherry and black chokecherry—are in poor condition and may have been that way when they arrived in Philadelphia. This may be why Frederick Pursh failed to recognize them as a new species and subspecies, respectively.[3]A. Scott Earle and James L. Reveal, Lewis and Clark’s Green World: The Expedition and its Plants (Helena, Montana: Farcountry Press, 2003); 165; James L. Reveal, Gary E. Moulton, and Alfred E. … Continue reading

Ripe Black Chokecherry Fruit

© 2013 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

The mature berries in the above photograph were growing below the Clearwater Canoe Camp in early October—the same time of year that the Lewis and Clark Expedition passed this location.

Lewis’s Decoction of Simples

An intriguing encounter with wild cherries—most likely the black chokecherry, the only variety of P. virginiana that grows in Montana—occurred the day Lewis and his “little party” left Decision Point to find the Falls of the Missouri. They reached a viewpoint on present-day Rowe Bench overlooking the slender Vimy ridge that separates the Missouri from the Teton River—”the point where Rose [Teton] River a branch Maria’s River approaches the Missouri so nearly.” They then pursued a herd of elk and were able to shoot and butcher four of them.[4]See also Harvesting the Hunt. As they prepared to have their midday meal, Lewis writes:

I was taken with such violent pain in the intestens that I was unable to partake of the feast of marrowbones. my pain still increased and towards evening was attended with a high fever . . . .

Unable to continue, camp was made, and Lewis reached into ‘nature’s medicine cabinet’ to find a remedy:

having brought no medecine with me I resolved to try an experiment with some simples[5]A simple, often the plural simples, was used here as a synonym for herbs: “a plant or herb employed for medical purposes.” Oxford English Dictionary, 1933 ed., s.v. “simple.”; and the Choke cherry which grew abundanly in the bottom first struck my attention; I directed a parsel of the small twigs to be geathered striped of their leaves, cut into pieces of about 2 Inches in length and boiled in water untill a strong black decoction of an astringent bitter tast was produced; at sunset I took a point [pint] of this decoction and abut an hour after repeated the dze by 10 in the evening I was entirely releived from pain and in fact every symptom of the disorder forsook me; my fever abated, a gentle perspiration was produced and I had a comfortable and refreshing nights rest.[6]Meriwether Lewis, 11 June 1805, Journals, 4:277–78.

Lewis may have learned to use the wild cherry as a gastrointestinal aid from his herbalist mother Lucy Marks. She in turn may have learned from the Mohegans who used the black cherry—Prunus serotina, the dominant species in Virginia—as an anti-diarrheal, cold remedy, and as a general tonic. As recorded by Gladys Tantaquidgeon, fermented black cherry juice was a Mohegan and Delaware remedy for dysentery and a spring tonic was made by steeping black cherry bark, sweet birch bark, dandelions, and several other roots.[7]Gladys Tantaquidgeon, “Mohegan Medicinal Practices, Weather-Lore and Superstitions” (Smithsonian Institution—Bureau of American Ethnology Annual Report, 1928), 43:264–270, … Continue reading When these botanical curatives were being recorded, there was considerable interchange between Eastern Tribal herbalists and herbalists of European descent. It is highly likely that a respected herbalist like Lucy Marks would be attuned to Native medicinal practices.[8]Lloyd G. Carr and Carlos Westey, “Surviving Folktales and Herbal Lore among the Shinnecock Indians of Long Island,” Journal of American Folklore 58 no. 228 (Apr.–Jun., 1945): 117, … Continue reading According to ethnobotanist Jeff Hart, “the drug from the chokecherry bark was introduced into American medicine about 1787 and appeared in the United States Pharmacopoeia about 1820.”[9]Jeff Hart, Montana Native Plants and Early Peoples (Helena: Montana Historical Society Press, 1976), 88.

Historic Uses

The Cheyennes and Yanktons were known to eat the fresh berries and preserve them in pounded cakes—pits and all—for winter use. The Cheyennes also added the dried berries to their pemmican. So important was this food source that the time to harvest the cherries was called by the Dakotas CHANPA SAPA WI—Ripe cherry month.[10]George Bird Grinnell, The Cheyenne Indians—Their History and Ways of Life, Vol. 2 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1972), 177, archive.org/details/cheyenneindiansv0002grin; Melvin R. … Continue reading In the American Southwest, black chokecherry was widely used for food and medicine similar to that described above. Additionally, the Navajo cooked the berries with cornmeal to make a mush even though the plant is not commonly found on their reservation.[11]Edward E. Castetter, “Uncultivated Native Plants Used as Sources of Food,” University of New Mexico Bulletin 4 no. 1 (1 May 1935), … Continue reading The Great Basin People made red dye from the fruit and red-brown dye from the inner bark. Southwest Tribes also used the wood to make bows, hoops, prayer sticks, and baskets.[12]Daniel E. Moerman, Native American Ethnobotany (Portland, Oregon: Timber Press, 1988), 448. Much of the ethnobotany for the Native Nations encountered by the Lewis and Clark Expedition, have been integrated with the record for the common chokecherry, Prunus virginiana.

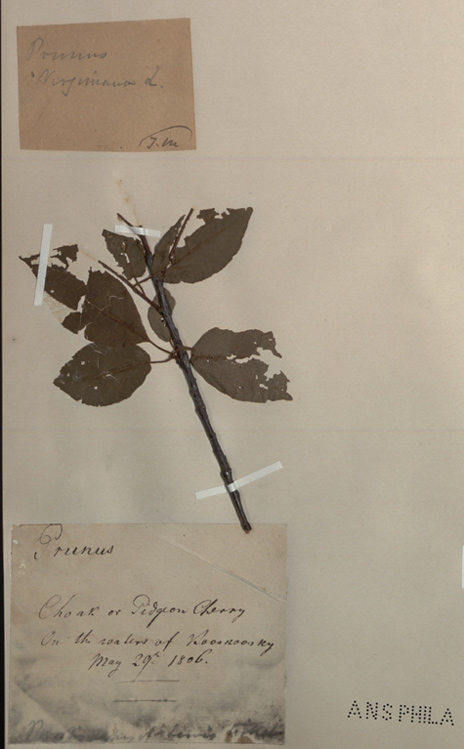

Lewis’s Specimen and Description

Lewis pressed the plant and wrote the botanical description on 29 May 1806, something he rarely did on the same day. The specimen survived the trip to St. Louis and is now housed in the Lewis and Clark Herbarium at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. Over the years, many botanists worked with the expedition specimens, and some of their notes can be seen in the accompanying figure which has been cropped for clarity. All the notes on the sheet are transcribed as follows:

Stamp: Deposited by American Philosophical Society

Handwritten Label

Prunus virginiana L.

T. M [Thomas Meehan]

Handwritten Label

Prunus

Choak or Pidgeon Cherry

On the waters of Kooskoosky

May 29th 1806.

Pursh’s copy of Lewis Ticket

Typewritten Label

Academy of Natural Sciences

Prunus virginiana var. demissa (Nutt.) Torr.

Det: Erica Armstrong Date: 17 May 1994

Handwritten on sheet: Moulton 141a

Printed Label

American Philosophical Society.

LEWIS & CLARK HERBARIUM.

FROM THE ATLANTIC TO THE PACIFIC.

Handwritten: Prunus Virginiana L.

[Locality, No., and Date left blank]

Perforation: ANS PHILA[13]Journals: Herbarium, 46, Plate 141a.

In his Long Camp description, Lewis used 39 botanical terms consistent with Benjamin Smith Barton‘s 1803 edition of Elements of Botany, one of the books in what historians call the “Traveling Library.” Most of Lewis’s botanical vocabulary can also be found in John Miller’s translation of Linnaeus, a two-volume set also in the traveling library.[14]Stephen Dow Beckham, Doug Erickson, et al., The Literature of the Lewis and Clark Expedition: A Bibliography and Essays (Portland, Oregon: Lewis & Clark College, 2003), 47–48, 52–53. President Thomas Jefferson asked Barton to mentor Lewis[15]See Lewis’s Friends and Mentors. in a letter dated 27 February 1803 and there is no doubt Barton and Miller influenced this description:

The Choke Cherry has been in blume since the 20th inst. it is a simple branching ascending stem. the cortex smooth and of a dark brown with a redish cast. the leaf is scattered petiolate oval accute at its apex finely serrate smooth and of an ordinary green. from 2½ to 3 inches in length and 1¾ to 2 in width. the peduncles are common, cilindric, and from 4 to 5 inches in length and are inserted promiscuously on the twigs of the preceeding years growth. on the lower portion of the common peduncle are frequently from 3 to 4 small leaves being the same in form as those last discribed. other peduncles ¼ of an inch in length are thickly scattered and inserted on all sides of the common peduncle at wright angles with it each elivating a single flower, which has five obtuse short patent white petals with short claws inserted on the upper edge of the calyx. the calyx is a perianth including both stamens and germ, one leafed fine cleft entire simiglobular, infrior, deciduous. the stamens are upwards of twenty and are seated on the margin of the flower cup or what I have called the perianth. the filaments are unequal in length subulate inflected and superior membranous. the anthers are equal in number with the filaments, they are very short oblong & flat, naked and situated at the extremity of the filaments, is of a yelow colour as is also the pollen. one pistillum. the germen is ovate, smooth, superior, sessile, very small; the Style is very short, simple, erect, on the top of the germen, deciduous. the stigma is simple, flat very short.—[16]Meriwether Lewis, 29 May 1806, Journals, 7:303.

Analysis of Botanical Terms

The table below gives a brief analysis of the botanical terms Lewis used to describe the black chokecherry. The first column is the term with Lewis’s alternate spellings—when they exist—given in square brackets.

| Term | Definition | Barton Count | Miller Count | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| acute [acutely, accute] |

“ending in an acute angle” Barton 32; “sharply pointed” Kew 7 | 9 | 69 | |

| anther | “a capsule or vessel, destined to produce or contain a substance [i.e. pollen] whose office is the impregnation of the germ, or female organ” Barton 161; “the part of the stamen holding the pollen” Kew 12 | 121 | 205 (Latin forms counted) | |

| apex | “tip or end . . . farthest removed from the base of insertion” Barton 43 | 18 | 71 | |

| calyx [calyx, calix] |

The group of outer leaves of the flower, Barton 107; Kew 24 | 193 | 270 | |

| claw | “the lower part of a many-petalled corolla, by which it is fixed to the receptacle” Barton 133; today the narrow part at the petal’s base, Kew 29 | 6 | 2 | |

| cleft | “cut into . . . segments or divisions” Barton 109 | 22 | 2 | |

| cortex | “Outer Bark” Barton 20; “bark or outer layer [antiquated term]” Kew 33 | 13 | 3 | |

| cylindrical [cylindric, cilindric, cilindrical, celindrical] |

“formed into a cylinder, or equal tube” Barton 165 | 26 | 47 | |

| deciduous | “falling off with the flower, that is the petals, the stamens, and the style” Barton 111 | 12 | 21 | |

| erect | “upright” Barton 72 | 11 | 106 | |

| filament [filaments, fillaments] |

“the more slender, or thread-like part of the stamen which supports the anther, and connects it with the flower” Barton 159 | 72 | 120 | |

| germ [germ, germen] |

“The Germen . . . the rudiment of the fruit in embryo-state” Barton 171; “the structure that holds the seeds—today called the ovary” Reveal. | 93 | 160 | |

| horizontal (root) [horrizontal, horizontal] |

“extends itself under the surface of the ground, nearly in a horizontal direction” Barton 14 | 10 | 0 | |

| inferior | “when the germ is above the base of the perianth” Barton 111; below the calyx, Kew 63 | 13 | 12 | |

| inflected | “bent upwards, at the end, towards the stem” Barton 42 | 7 | 7 | |

| margin | “edge” Barton 33 | 21 | 0 | |

| membranous | “flexible and thin” Kew 72; Barton 192 | 30 | 26 | |

| naked | “a stem devoid of leaves and hair” Barton 22 | 55 | 13 | |

| oblong | “longer than broad” Kew 78; Barton 162 | 14 | 147 | |

| obtuse | “blunt” Barton 32 | 15 | 84 | |

| ovate | “egg-shaped” Barton 31 | 14 | 114 | |

| patent | “spreading” Barton 160, as patens | 5 (as patens) | 51 | |

| peduncle | “a partial stem, or trunk, which supports the fructification, without the leaves” Barton 71 | 51 | 21 | |

| perianth | “flower-cup” Barton 107; “collective term for the calyx and corolla” Kew 86 | 111 | 95 | |

| petiolate [petiolate, peteolate] |

“growing on a petiole or foot stalk” Barton 41; “with a leaf stalk” Kew 87 | 4 | 1 | |

| pistillum | “the female part of the vegetable . . . . it consists of three parts, the Germen, the Stylus, and the Stigma” Barton 170–1; today the pistil with “ovary, style and stigma” Kew 90 | 5 | 109 | |

| pollen | “fecundating powder of the stamens,” Barton 99; “powder-like fertilising agent” Kew 91 | 51 | 12 | |

| scattered | “without any regular order” Barton 71 | 6 | 2 | |

| semiglobular | semi-spherical, Kew 53, 107; Barton 134 (globular) | 0 [globular used 19 times] | 0 [globular used 5 times] | |

| serrate | “toothed like a saw” Barton 32 | 8 | 7 | |

| sessile [sessile, sissile] |

generally meaning attached directly without a stalk, Barton 41; Kew 108 | 25 | 13 | |

| simple | “not divided” Barton 172 | 11 | 92 | |

| simple branching | “does not divide” Barton 22 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| smooth [smooth, smoth, mothe] |

“beardless” Barton 91; not rough or hairy, Kew 110 | 17 | 13 | |

| stamen | the male organ, Barton 108, “the filamentum, and the anther” Barton 158 | 240 | 188 | |

| stigma | “the summit or top of [the] female part of the plant . . . destined to receive the influence of the pollen, and transmit it to the germ” Barton 175 | 55 | 121 | |

| style | “the middle portion of the pistil, which, in many plants, connects the stigma with the germ” Barton 172 | 71 | 128 | |

| subulate | “awl-shaped” Barton 89 | 12 | 60 | |

| superior | “attached above, as an ovary that is attached above the point of attachment of the other floral whorls” Harris 117 | 14 | 13 |

The above definitions come primarily from:

- Benjamin Smith Barton, Elements of Botany: or Outlines of the Natural History of Vegetables (Philadelphia: 1803), www.google.com/books/edition/Elements_of_Botany_Or_Outlines_of_the_Na/Hk0aAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0.

When appropriate, additional modern definitions have been given for additional clarity or when today’s definition has changed. The modern definitions come from:

- Henk Beentje, The Kew Plant Glossary: An Illustrated Dictionary of Plant Terms (Royal Botanic Gardens: Kew Publishing, 2012).

- James G. Harris and Melinda Woolf Harris, Plant Identification Terminology: An Illustrated Glossary (Spring Lake, Utah: Spring Lake Publishing, 2009).

- James L. Reveal, on this website in Camas. See also by Reveal, Lewis as Botanist.

When not enclosed with quotation marks, the definition has been paraphrased from the given source.

In the two columns of word counts, every effort has been made to count only those instances where the intended meaning is the one given in the definition. Alternate forms—for example, claw, claws, clawed—have been counted. Latin equivalents have been excluded from the count except when they are used exclusively by the author.

John Miller’s counts come from his two-volume translation:

- John Miller, An Illustration of the Sexual System, Of Linnaeus (London, 1779), books.google.com/books/about/An_Illustration_of_the_Sexual_System_Of.html?id=ak8-AAAAcAAJ.

- John Miller, An Illustration of the Termini Botanici of Linnaeus (London, 1789), archive.org/details/illustrationofse02mill.

Notes

| ↑1 | See Frazer’s Razor and Ordway’s Salmon Fishing Trip. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | U.S. Department of Agriculture, “PLANTS Database,” plants.usda.gov/home/plantProfile?symbol=PREM, accessed 18 March 2023. |

| ↑3 | A. Scott Earle and James L. Reveal, Lewis and Clark’s Green World: The Expedition and its Plants (Helena, Montana: Farcountry Press, 2003); 165; James L. Reveal, Gary E. Moulton, and Alfred E. Schuyler, “The Lewis and Clark Collections of Vascular Plants: Names, Types, and Comments,” Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 149 (29 January 1999), 41; Journals, Gary Moulton, ed., 7:307n2. |

| ↑4 | See also Harvesting the Hunt. |

| ↑5 | A simple, often the plural simples, was used here as a synonym for herbs: “a plant or herb employed for medical purposes.” Oxford English Dictionary, 1933 ed., s.v. “simple.” |

| ↑6 | Meriwether Lewis, 11 June 1805, Journals, 4:277–78. |

| ↑7 | Gladys Tantaquidgeon, “Mohegan Medicinal Practices, Weather-Lore and Superstitions” (Smithsonian Institution—Bureau of American Ethnology Annual Report, 1928), 43:264–270, library.si.edu/digital-library/book/annualreportofbu43smithso; Gladys Tantaquidgeon, “Folk Medicine of the Delaware and Related Algonkian Indians,” Anthropological Series No. 3 (Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Historical Commission, 1972), archive.org/details/folkmedicineofde00tant_0/. |

| ↑8 | Lloyd G. Carr and Carlos Westey, “Surviving Folktales and Herbal Lore among the Shinnecock Indians of Long Island,” Journal of American Folklore 58 no. 228 (Apr.–Jun., 1945): 117, https://www.jstor.org/stable/535500. |

| ↑9 | Jeff Hart, Montana Native Plants and Early Peoples (Helena: Montana Historical Society Press, 1976), 88. |

| ↑10 | George Bird Grinnell, The Cheyenne Indians—Their History and Ways of Life, Vol. 2 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1972), 177, archive.org/details/cheyenneindiansv0002grin; Melvin R. Gilmore, 1913, “Some Native Nebraska Plants with Their Uses by the Dakota,” Collections of the Nebraska State Historical Society 17: 364–65, www.usgennet.org/usa/ne/topic/resources/OLLibrary/collections/vol17/v17p358.htm. |

| ↑11 | Edward E. Castetter, “Uncultivated Native Plants Used as Sources of Food,” University of New Mexico Bulletin 4 no. 1 (1 May 1935), digitalrepository.unm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1022&context=unm_bulletin. |

| ↑12 | Daniel E. Moerman, Native American Ethnobotany (Portland, Oregon: Timber Press, 1988), 448. |

| ↑13 | Journals: Herbarium, 46, Plate 141a. |

| ↑14 | Stephen Dow Beckham, Doug Erickson, et al., The Literature of the Lewis and Clark Expedition: A Bibliography and Essays (Portland, Oregon: Lewis & Clark College, 2003), 47–48, 52–53. |

| ↑15 | See Lewis’s Friends and Mentors. |

| ↑16 | Meriwether Lewis, 29 May 1806, Journals, 7:303. |