Jean Baptiste Charbonneau’s education began in a Hidatsa village. In St. Louis at the age of five or six, his classical education began under the guardianship of William Clark.

Knife River Villages

If William Clark had his way on 17 August 1806, the Charbonneau family would have left the Knife River India Villages and continued with the Lewis and Clark Expedition to St. Louis. St. Louis offered income for Toussaint Charbonneau, European comforts for Sacagawea, and a formal education for Jean Baptiste Charbonneau. Clark did his best to persuade them in a letter dated 20 August—see An offer to Raise Jean Baptiste. Regarding Jean Baptiste, Clark proposed:

As to your little Son (my boy Pomp) you well know my fondness for him and my anxiety to take and raise him as my own child. I once more tell you if you will bring your son Baptiest to me I will educate hime and treat him as my own child . . . . [1]Clark to Toussaint Charbonneau in Donald Jackson, ed. Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents: 1783-1854, 2nd ed., (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 315–16.

Jean Baptiste’s parents had agreed to bring the lad to St. Louis after he had aged another year. By that time, the Arikaras had made travel between the Knife River Villages and St. Louis difficult. The Charbonneaus would not arrive until late 1809. Jean Baptiste’s toddler years were, therefore, shaped in the villages at the Knife River, likely the Hidatsa village Awatixa where his parents lived before his birth on 11 February 1805.

His Hidatsa early childhood education layed the foundations for hunting, horsemanship, and ceremonial ways such as games, rituals, dances, and prayers. The Knife River Villages were also a trading hub where the toddler would have been around individuals from other Native Nations—namely the Crows and Assiniboines—who made annual trips to trade at the Knife River. Also at the villages were European and Metis traders from the Hudson’s Bay Company and North West Company as well as a handful of independents. Here, Jean Baptiste was exposed to several languages and cultures. All this would come into use during his long and colorful life—see Jean Baptiste, Mountain Man and Jean Baptiste, Military Guide, and Jean Baptiste in California.

Setting Up in St. Louis

From written records, we know that the Charbonneau family was in St. Louis by December 1809—See The Charbonneaus in St. Louis. Nearly a year later, Toussaint would try his hand at farming, but after five months, he sold his land back to Clark and with “sickly” Sacagawea headed back up the Missouri to work for Manuel Lisa as a trader and interpreter.[2]Harold P. Howard, Sacajawea (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1971), 156, archive.org/details/sacajawea00howa; “sickly” comes from Henry A. Brackenridge, Journal of a Voyage Up the … Continue reading Jean Baptiste, now six years old in April 1811, remained in St. Louis under the care of William Clark. There also was Toussaint Jusseaume—the teenage son of expedition interpreter René Jusseaume and indentured servant of Meriwether Lewis. He was 13 when he arrived in St. Louis in 1809. We do not know if either Jean Baptiste and Toussaint Jusseaume lived in the same house as Clark and his new wife, Julia. [3]Susan M. Colby, Sacagawea’s Child: The Life and Times of Jean-Baptiste (Pomp) Charbonneau (Spokane, Washington: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 2005), 91n36; Albert Furtwangler, … Continue reading

On 20 December 1812, sometime after the birth of his sister Lizette, Jean Baptiste’s mother was reported to have “died from a putrid fever” at Manuel Lisa’s Fort Lisa.[4]John C. Luttig, Journal of a Fur-trading Expedition on the Upper Missouri 1812–1813, Stella M. Drumm, ed. (St. Louis: Missouri Historical Society, 1920), 106; confirmed by Clark’s note … Continue reading Conditions among the Indians deteriorated such that the fort’s clerk, John Luttig, wrote “we are constant watching in our careful Situation, we hear and see nobody from all around us, and are like Prisoners in Deserts to expect every moment our fate.”[5]Luttig, 127. While Toussaint Charbonneau was out trying to calm things down among the Hidatsa and Arikara, Luttig abandoned the fort. He brought Lizette to St. Louis and on 11 August 1813 had a Missouri court give him guardianship of both Lizette and Jean Baptiste.

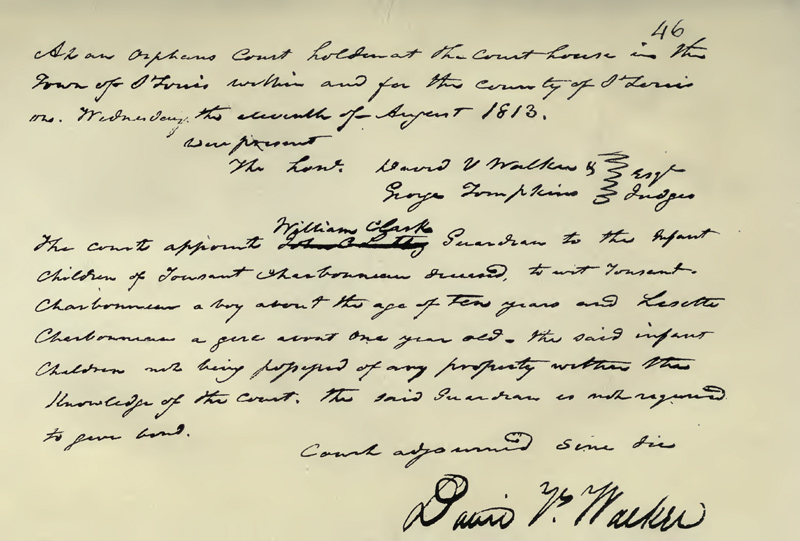

Transcript of the Orphans Court document (see figure):

46

At an Orphans Court hold[ing?] at the Court house in this Town of St. Louis within and for the county of St. Louis [on?] Wednesday this eleventh of August 1813.

here present

The hone. David V. Walker &

George Tompkins

Esq. Judges

The court appoints John C. Luttig William Clarke Guardian to the Infant children of Tousant Charbonneau deceased, to wit Toussant Charbonneau, a boy about ten years old, and a girl, Lisette Charbonneau, about one year old. The said infant children not being [disposed, possessed] of any property within the Knowledge of the Court, the said Guardian is not required to give bond.

Court adjourned Sine die

[DAVID V. WALKER][6]Luttig, facing page 106.

For many years, the name “Tousant” on the court record led some early historians to believe there was a second Charbonneau son named Toussaint. Most historians, however, believe that Toussaint and Jean Baptiste are one and the same. By July 1815, Luttig had died, and the guardianship was assigned to William Clark.

Jean Baptiste, now 10 years old, continued under Clark’s guardianship, but of his schooling and boarding during this time, little is known. There were no public schools in St. Louis until 1838, so his education most likely came from tutoring and private schools.

Private Schooling

Not until the establishment of Bishop DuBourg’s—also found in literature as Duborg, Du Bourg and Dubourg—St. Louis College in 1818 can one get a fuller picture of Jean Baptiste’s St. Louis education. DuBourg came to St. Louis with impeccable credentials and an Enlightenment attitude. Clark helped secure financing for the school and sent two of his own sons there.[7]Colby, 93.

What little we know of Jean Baptists private schooling comes from Clark’s 1820 list of expenditures as Superintendent of Indian Affairs. These have been assembled into the following table.[8]“Abstract of Expenditures by Captain W. Clark as Superintendent of Indian Affairs,” A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774 – 1875, … Continue reading

| Date of payment. | No. of vou. | Payments, to whom made. | Nature of the disbursements. | Amount. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1820. | ||||

| [Jan.] 22 p. 291 | 118 | J. E. Welch | For two quarter’s tuition of J. B. Charboneau, a half Indian boy, and firewood and ink | 16 37 1/2 |

| April 1 | 128 | J. & G. H. Kennerly[9]Clark’s records for 1820 and 1821 include several purchases of Indian gifts and supplies purchased from brothers James and George Hancock Kennerly. James Kennerly came from Kentucky to St. … Continue reading | For one Roman History for Charboneau, a half Indian, $1 50; one pair of shoes for ditto, $2 25; two pair socks for ditto, $1 50; six yards coarse linen, $3; ten yards domestic, $5; one quire paper and quills for Charboneau, $1 50; one Scott’s Lessons for ditto, $1 50; one dictionary for ditto, $1 50; one hat for ditto, $4; four yards of cloth for ditto, $10 . . . one slate and pencils, 62 cents, for Charboneau . . . six yards corduroy for Charboneau, $5 25; one hat for Charboneau, $4; one pair of shoes for ditto, $2 50 . . . . | 368 47 |

| [April] 11 | 132 | J. E. Welch | For one quarter’s tuition of J. B. Charboneau, a half Indian boy, including fuel and ink | 8 37 1/2 |

| May 17 | 139 | F. Neil | For one quarter’s tuition of Toussaint Charboneau, a half Indian boy | 12 00 |

| [June] 30 | 170 | L. T. Honoré[10]On 30 October 1819, Louis Tesson Honoré was one of several community members who signed a document authorizing the Catholic Church to build a house for lodging “the Clergy of our Church, and … Continue reading | For board, lodging, and washing of J. B. Charboneau, a half Indian boy, from 1st April to 30th June | 45 00 |

| Oct. 1 | 203 | L. T. Honoré | For boarding, lodging, and washing of J. B. Charboneau, from 1st July to September, 1820, at $15 per month | 45 00 |

| [Dec.] 31 | 233 | L. T. Honoré | For boarding, lodging, and washing of J. B. Charboneau, from 1st October to 31st December, 1820, at $15 per month | 25 00 |

DuBourg Hall

St. Louis University

© 2005 by Wilson Delgado. Released by the creator to the Public Domain, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Slu_dubourg_1888.jpg.

DuBourg Hall was built as a tribute to the institution’s embryonic years as DuBourg’s St. Louis College. Construction started in 1888 at a new location, now the oldest building of Saint Louis University.[11]“Saint Louis University,” Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saint_Louis_University, accessed 6 June 2023.

James E. Welch was a Baptist missionary who opened an academy near the Post Office in 1818. The Reverend Francis Niel, under the direction of Bishop DuBourg, opened an academy on 16 November 1818.[12]Billon, 80. By 1820, it was called “Bishop Dubourg’s College” and had eight professors working under Niel. It eventually became St. Louis University and claims Jean Baptiste as an alumnus.[13]Billon, 81; Colby, 94.

Duke Paul Wilhelm of Württemberg, who visited the United States in 1823 and changed the trajectory of Jean Baptiste’s life—see Jean Baptiste in Europe—described DuBourg’s school in favorable terms:

The houses recently erected as also the church are built of brick. The interior of the church is decorated with a few paintings which Mr. Du Bourg brought along from France, and in the bishop’s dwelling a library, quite large for St. Louis has been collected. With praiseworthy generosity this genteel man has not withdrawn these books from public use.

The bishop’s house is very much crowded, since a part assigned to Mr. Du Bourg himself has been surrendered by him for school purposes . . . . Besides these schools under the direction of the Catholic clergy in St. Louis, several other educational institutions that headed by Americans and Englishmen.[14]Paul Wilhelm, Duke of Württemberg, Travels in North America 1822–1824, Savoie Lottinville, ed., trans. W. Robert Nitske (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1973), 200–201, … Continue reading

Of special interest is that Clark asked the U.S. Government to pay the expense of boarding and educating Jean Baptiste. This is very different from Clark’s original offer in 1806 to “raise him as my own child.” At the time, the Indian Department was increasingly active in educating young Native Americans and the idea of Indian Schools was percolating within inner circles in Washington City. It is not inconceivable that by submitting these expenses, Clark was following his superior’s expectations rather than trying to squeeze a dime from the government.

The year 1820 was especially difficult for Clark. His wife Julia passed away, and he lost his bid for governor of Missouri. Also notable is that the last expense listed is only $25. The full quarter’s boarding would have been $45. This suggests Jean Baptiste may have moved out of Honoré’s care in mid-November. He would have been 15, so it is possible that he started his employment with Auguste Chouteau at this time.

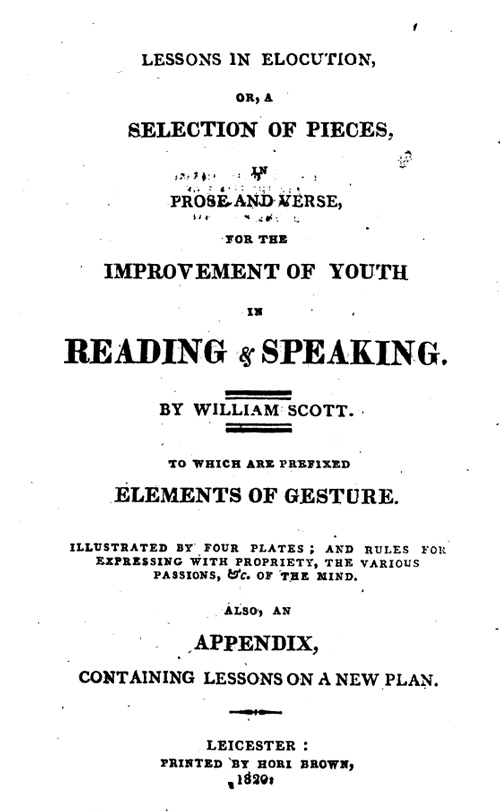

Jean Baptiste’s Lesson Book

Clark’s expense ledger for 1 April 1822 lists one “Scott’s Lessons for ditto [Jean Baptiste], $1 50.” The 1820 edition of this textbook is titled:

Lessons in Elocution

or, a

Selection of Pieces,

in

Prose and Verse,

for the

Improvement of Youth

in

Reading & Speaking.

by William Scott.

to which are prefixed

Elements of Gesture.

Illustrated by four plates; and rules for

expressing with propriety, the various

passions, &c. of the mind.

A cursory examination of Scott’s Lessons—available online—reveals the classical nature of Jean Baptiste’s education at DuBourg’s St. Louis Academy.[15]William Scott, Lessons in Elocution . . . (Leicester: Hori Brown, 1820) www.google.com/books/edition/Lessons_in_Elocution_Or_A_Selection_of_P/8p8AAAAAYAAJ.

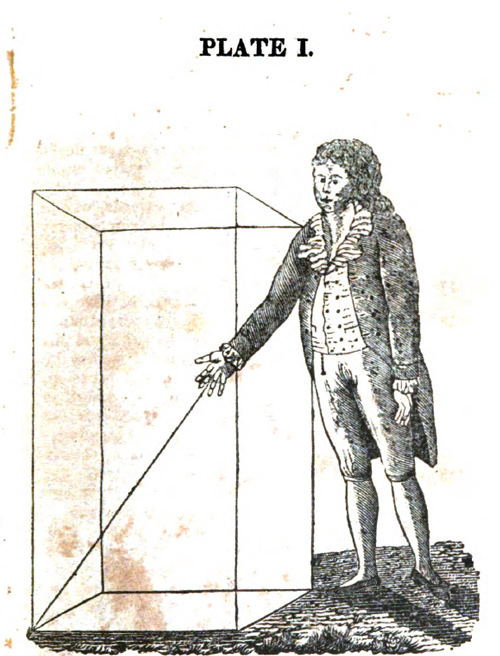

Scott’s Elements of Gesture

The textbook begins with a 37-page section titled “Elements of Gesture” that provides detailed instruction for presenting oneself during public speeches. Below are two of the four plates and excerpts of the text that accompanies them.

Scott’s Lessons, Plate I

From Scott’s Lessons, 1820 edition.

Plate I, represents the attitude in which a boy should always place himself when he begins to speak, He should rest the whole weight of his body on the right leg; the other, just touching the ground, at the distance at which it would naturally fall, if lifted up to show that the body does not bear upon it . . . . The position of the arm, perhaps will be best described, by supposing an oblong hollow square formed by the measure of four arms as in plate I, where the arm in its true position, forms the diagonal of such an imaginary figure, So that if line were drawn at right angles from the shoulder, extending downwards, forwards and sideways, the arm will form an angle of forty-five degrees every way.

When the pupil has pronounced one sentence, in the position thus described, the hand, as if lifeless, must drop down to the side, the very moment the last accented word is pronounced; and the body, without altering the place of the feet, poise itself on the left leg, while the left hand raises itself, into exactly the same position as the right was before, and continues in this position till the end of the next sentence, when it drops down on the side as if dead; and the body, poising itself on the right leg as before, continues with the right arm extended, till the end of the succeeding sentence; and so on, from right to left, and from left to right, alternately, till the speech is ended.[16]Scott, 10, 15.

Scott’s Lessons, Plate I

From Scott’s Lessons, 1820 edition.

When the pupil has got the habit of holding his hand and arm properly, he may be taught to move it . . . . the whole arm, with the elbow, forming nearly an angle of a square, should move upwards from the shoulder, in the same position as when gracefully taking off the hat . . . . when it approaches to the head, the arm should, with a jerk, be suddenly straightened into its first position, at the very moment the emphatical word is pronounced. The coincidence of the hand and voice, will greatly enforce the pronunciation; and, if they keep time, they will be in tune, as it were, to each other; and to force and energy, add harmony and variety.[17]Scott, 16.

One can only wonder if Jean Baptiste followed Scott’s advice while telling stories with fellow campers in the frontier west. Did he assume the stance shown in Plate 1 when telling tales to trappers, guides, hunters, soldiers, emigrants, and gold miners? Whether he did or not, we know that many though him an engaging presenter.

Scott’s First Lesson

Following “Elements of Gesture” is the section titled “Lessons in Reading.” Below is the beginning of the first lesson—sentences selected from Introduction to the Art of Thinking by Henry Home, Lord Kames’ (1695–1782).[18]Kames’ original text is available at archive.org/details/introductiontoa00kamegoog/.

- Man’s chief good is an upright mind, which no earthly power can bestow, or take from him.

- We ought to distrust our passions, even when they appear the most reasonable.

- It is idle as well as absurd to impose our opinions upon others. The same ground of conviction operates differently on the same man in different circumstances, and on different men in the same circumstances.

- Choose what is most fit; custom will make it the most agreeable.

- A cheerful countenance betokens a good heart.

- Hypocrisy is a homage that vice pays to virtue.

- Anxiety and constraint are the constant attendants of pride.

- Men make themselves ridiculous, not so much by the qualities they have, as by the affectation of those they have not.

- Nothing blunts the edge of ridicule so effectually as good humor.

- To say little and perform much, is the characteristic of a great mind.

Scott’s Table of Contents

Scott’s table of contents reveals inclusion of many great minds, from Homer to Chesterfield. For example:

- “The honour and advantage of a constant adherence to truth” from Percival’s Tales

- “Impertinence in discourse” by Theophrastus (c. 371–c. 287 BC)

- “Advantages of History” by David Hume (1711–1776)

- “Awkwardness in company” by Philip Dormer Stanhope, Earl of Chesterfield (1694–1773)

- “On the order of nature” by Alexander Pope (1688–1744)

- “Lamentation for the loss of sight” by John Milton (1608–1674)

- “Parting of Hector and Adromache” by Homer (born 8th century BC)

- “Cicero for Milo” by Cicero (106–43 BC)

- “Hannibal to the Carthaginian army” by Robert Hooke (1635–1703)

- “Aeneas to Queen Dido” by Virgil (70–19 BC)

- “Speech of Henry V. at the siege of Harfleur” by Shakespeare (1564–1616)

There is no record of Jean Baptiste quoting the classics during his tenure in the frontier west, but several people he would meet mentioned he had classical training. For many mountain men, classical literature was a highly desired and welcome diversion.

Notes

| ↑1 | Clark to Toussaint Charbonneau in Donald Jackson, ed. Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents: 1783-1854, 2nd ed., (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 315–16. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Harold P. Howard, Sacajawea (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1971), 156, archive.org/details/sacajawea00howa; “sickly” comes from Henry A. Brackenridge, Journal of a Voyage Up the Missouri River Performed in Eighteen Hundred and Eleven (Baltimore: Coale and Maxwell, 1816) 32–33, archive.org/details/br00ackenridgesjoubracrich/; The Mountain Men and the Fur Trade of the Far West, Le Roy Hafen, ed. (Glendale, California: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 1969), 9:57. |

| ↑3 | Susan M. Colby, Sacagawea’s Child: The Life and Times of Jean-Baptiste (Pomp) Charbonneau (Spokane, Washington: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 2005), 91n36; Albert Furtwangler, “Sacagawea’s Son as a Symbol,” Oregon Historical Quarterly 102, no. 3 (2001): 303, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20615158. |

| ↑4 | John C. Luttig, Journal of a Fur-trading Expedition on the Upper Missouri 1812–1813, Stella M. Drumm, ed. (St. Louis: Missouri Historical Society, 1920), 106; confirmed by Clark’s note 1825–28, “Men on Lewis & Clark’s Trip,” in Letters, Donald Jackson, 638. |

| ↑5 | Luttig, 127. |

| ↑6 | Luttig, facing page 106. |

| ↑7 | Colby, 93. |

| ↑8 | “Abstract of Expenditures by Captain W. Clark as Superintendent of Indian Affairs,” A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774 – 1875, American State Papers, House of Representatives, 17th Congress, 1st Session, Indians Affairs: Volume 2, page 289, memory.loc.gov. |

| ↑9 | Clark’s records for 1820 and 1821 include several purchases of Indian gifts and supplies purchased from brothers James and George Hancock Kennerly. James Kennerly came from Kentucky to St. Louis in October 1813. He ran a store in “Clark’s new brick house on 55 North Main Street,” sometimes called “Clark’s Store,” until 1820 when he built a new residence and store at the north lot next door. He is the father of William Clark Kennerly who was with Jean Baptiste and William Drummond Stewart in 1843. (Frederic L. Billon, Annals of St. Louis in its Territorial Days from 1804 to 1821 . . . . (St. Louis: 1888), 266–68, 285). |

| ↑10 | On 30 October 1819, Louis Tesson Honoré was one of several community members who signed a document authorizing the Catholic Church to build a house for lodging “the Clergy of our Church, and the keeping of a school for the education of youth.” (Billon, 421–22) He is listed on 31 March 1821 as an interpreter who received a payment of $100. (“Abstract of Expenditures,” 298). |

| ↑11 | “Saint Louis University,” Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saint_Louis_University, accessed 6 June 2023. |

| ↑12 | Billon, 80. |

| ↑13 | Billon, 81; Colby, 94. |

| ↑14 | Paul Wilhelm, Duke of Württemberg, Travels in North America 1822–1824, Savoie Lottinville, ed., trans. W. Robert Nitske (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1973), 200–201, archive.org/details/travelsinnortham0000paul. |

| ↑15 | William Scott, Lessons in Elocution . . . (Leicester: Hori Brown, 1820) www.google.com/books/edition/Lessons_in_Elocution_Or_A_Selection_of_P/8p8AAAAAYAAJ. |

| ↑16 | Scott, 10, 15. |

| ↑17 | Scott, 16. |

| ↑18 | Kames’ original text is available at archive.org/details/introductiontoa00kamegoog/. |