Alcalde of San Luis Rey

Near the end of the year he arrived in California with the Mormon Battalion, Jean Baptiste Charbonneau was appointed as acalde of San Luis Rey de Francia, a once-prosperous Spanish mission at present-day Oceanside, California.

San Luis Rey Mission

San Luis Rey Mission, Oceanside, 1895

by Louis Kinney Harlow (1850–1913)

Courtesy U.S. Library of Congress, cdn.loc.gov/master/pnp/pga/14200/14228u.tif. Image is in the Public Domain.

During the Mexican–American War of 1846–48, Topographical Engineer Lt. William H. Emory described the mission just days before the arrival Jean Baptiste’s Mormon Battalion:

Six and a half miles march brought us to the deserted mission of San Luis Rey. The keys of this mission were in charge of the alcalde of the Indian village, a mile distant. He was at the door to receive us and deliver up possession.

This building is one which, for magnitude, convenience, and durability of architecture, would do honor to any country.

The walls are adobe, and the roofs of well made tile. It was built about sixty years since by the Indians of the country, under the guidance of a zealous priest. At that time the Indians were very numerous, and under the absolute sway of the missionaries. These missionaries at one time bid fair to christianize the Indians of California. Under grants from the Mexican government, they collected them into missions, built immense houses, and commenced successfully to till the soil by the hands of the Indians for the benefit of the Indians.

The habits of the priests, and the avarice of the military, rulers of the territory, however, soon converted these missions into instruments of oppression and slavery of the Indian race.[1]William H. Emory, Notes of a Military Reconnaissance, from Fort Leavenworth, in Missouri, to San Diego (Washington: Wendell and Van Benthuysen, Printers, 1848), 116, … Continue reading

Soon after Emory’s arrival, a garrison was established there under the charge of U.S. Army Captain and Indian sub-agent J. D. Hunter. Hunter was given instructions to encourage priests to return and to allow the mission to keep any agricultural harvest they produced. Hunter and Charbonneau got on well, and by November 1847 Jean Baptiste was appointed as the new alcalde—a type of civilian magistrate and Indian sub-agent whose duties included gathering statistics, keeping the “gentiles” in check, and caring for and protecting Indian servants.[2]R.B. Mason, U.S. Army Colonel and California Governor, 2 August 1847 in Zephyrin Englehardt, San Luis Rey Mission (San Francisco: The James H. Barry Company, 1921), 145–46, … Continue reading The California alcaldes were not government officials, but respected community members who volunteered their time to give advice and settle disputes. In his position, Jean Baptiste received no pay, but his decisions sometimes changed the lives of those brought before him.

Trials as Alcalde

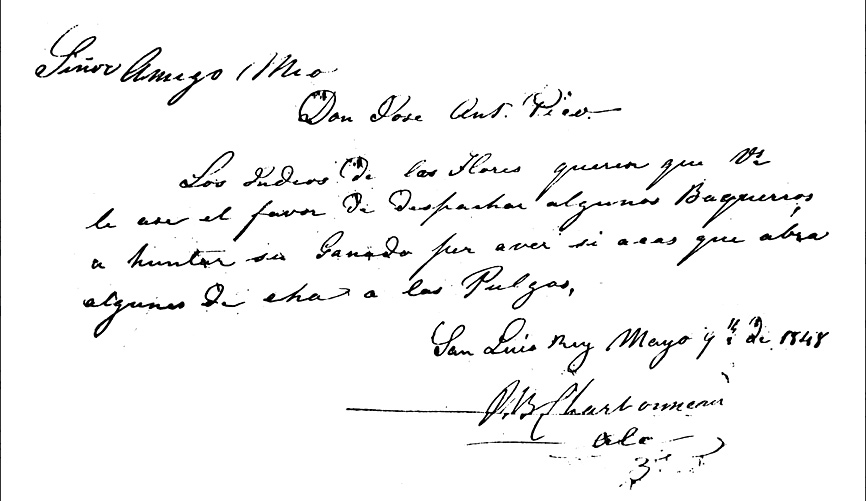

From this period, we have two notes written by Jean Baptiste. The possibility exists that either is a clerk’s copy, but the elaborations in the second note’s signatures and similarity in penmanship between the two, suggest both notes are his hand.

The above note, dated May 1848 and written in Spanish, relays a request from the local Indians for help rounding up livestock.[3]Dane Bevan, “From Jean Baptiste Charbonneau,” Oregon History Project, www.oregonhistoryproject.org/articles/historical-records/from-jean-baptiste-charbonneau/ accessed 9 June 2023.

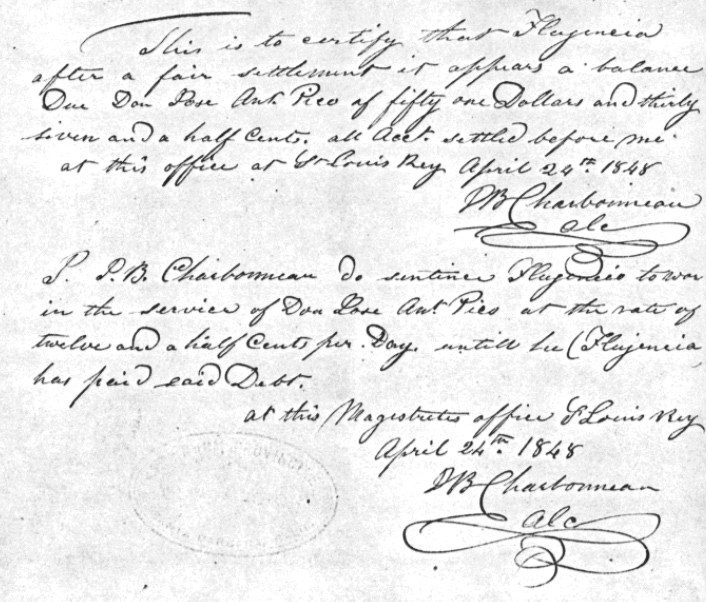

Decision in Pico v. Flujencia

Original from the Santa Barbara Archives.[4]Irving W. Anderson, “J. B. Charbonneau, Son of Sacajawea,” Oregon Historical Quarterly, 71, no. 3 (Sep., 1970): 260, www.jstor.org/stable/20613180.

At the same time that Jean Baptiste received his appointment, local resident José Antonio Pico was ordered to turn over any mission property in his possession. Mission records show that he had been selling goods and liquor to the local Paisanos. On 29 November, Governor Mason forbade all sale of alcohol to Native Americans in California.[5]Bancroft, 5:568. Pico turned his attention to debts previously accrued by bringing a case before Jean Baptiste to collect from one Flujencia, a local resident. He asked for $109.87½, yet Charbonneau’s award (shown above) was less than half that amount:

This is to certify that Flujencia after a fair settlement it appears a balance Due Jose Ant. Pico of fifty one Dollars and thirty seven and a half Cents. all Acct. settled before me at this office at St. Louis Rey April 24th. 1848

J. B. CHARBONNEAU, Alc.

Through his decision, Jean Baptiste likely became an enemy of one the most powerful men in the region prior to the takeover by the United States. Perhaps worse, he had to order Flujencia to pay up through manual labor:

I, J. B. Charbonneau do sentence Flujencia to work in the service of Don Jose Ant. Pico at the rate of twelve and a half Cents per Day, until he (Flujencia) has paid said Debt.

At this Magistrate’s office S. Louis Rey

April 24th. 1848

J. B. CHARBONNEAU

Alc.[6]Englehardt, 147–151.

The math suggests that it would take the rest of Flujencia’s lifetime to repay this debt. Despite this harsh decision, some complained that Jean Baptiste favored the Indians too much. In a letter enclosed with his resignation as alcalde in 1848, Hunter suggests:

a half-breed Indian of the U.S. [Charbonneau] is regarded by the people as favoring the Indians more than he should do, and hence there is much complaint against him.[7]“J.F. Stevenson to Gov. Mason,” July 24, 1848, in Ann W. Hafen, French Fur Traders and Voyageurs in the American West, LeRoy R. Hafen, ed. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1993), … Continue reading

From the written record of his life, it appears that Jean Baptiste Charbonneau was energetic, positive, and cheerful—the type of person adverse to worry and in search of joy. Alcalde Jean Baptiste was unlikely to tolerate unfair accusations and the enmity of those like Pico.[8]In a letter written by Jean Baptiste, Ann Hafen provides: “I am prepared to prove that the Indian Paulino is guilty of what he has sworn to my charge, and I will prove in the trial that he has … Continue reading Perhaps the prospect of California gold provided better opportunities and an escape from the stress of public service..

Auburn Miner

After his stint as alcalde, Jean Baptiste found a place he would live for nineteen years—the gold-rich gulches surrounding present-day Auburn, California.

Auburn Ravine Miner, 1852 (cropped)

by Joseph Blaney Starkweather

From an original daguerreotype, courtesy California State Library, DAG-0103, csl.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/view/delivery/01CSL_INST/12136584150005115.

In addition to Mormon Battalion veterans and Shoshone-Métis Jean Baptiste, Auburn held a diverse population. In 1852, Chinese miners made up about 33% of the male population, and Auburn’s “China Town” was placed in the heart of the city, neither underground nor removed. Later, Chinese people living in Auburn appear to have escaped the hostilities that arose in other California towns. During the gold rush years, African American miners in California sent about $750,000 to their families in the south. California was a slave-free state not so much on moral grounds, but because the miners did not want to compete with miners who had them.[9]Art Sommers, John Knox, and April McDonald-Loomis, Images of America: Early Auburn (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2015), 35, 38, 75. Many languages were heard in the Auburn gulches, and Jean Baptiste’s multilingual skills likely served him well in such a place.

Murderer’s Bar

Before Jean Baptiste’s arrival at Auburn, three men—Thomas Buckner, Captain Ezekiel Merritt, and Peg—likely Merritt’s slave—established a placer mine across from Murderer’s Bar on the Middle Fork of the American River. At Murderer’s Bar, they found the burned remains of a deadly fight between some miners and Native Americans.

Seeking a defensive position, Buckner’s party moved to the other side of the river. Buckner’s Bar, as it would be called, paid well, but Merritt left forever and his “servant” eventually followed in search of his master. Now alone, Buckner feared for his safety. Myron Angel tells of his reaction to the arrival of Jean Baptiste and two other miners:

Tom Buckner’s heart was gladdened by the appearance of other men, not hostile, at his camp, in the person of J. B. Charbonneau, Jim Beckwourth[10]Legally named Beckwith, James Pierson Beckwourth (1798/1800–1566) had been born into slavery in Virginia. He became a free man of multiracial decent and worked as a fur trapper, explorer, scout, … Continue reading and Sam Myers, all noted mountaineers; and from that time onward came large crowds of gold-seekers, so that before the end of July, the river banks fairly swarmed with humanity above and below him for many miles.[11]Myron Angel, ed. History of Placer County, California . . . (Oakland: Thompson & West, 1882), 68–71, www.archive.org/details/historyofplacerc00ange.

A nearly identical description—likely Angel’s original source—is given in The Placer Herald, 24 June 1849 with the three new men described as “white.” This is especially ironic given that Jean Baptiste was a Metis “halfbreed” and Beckwourth was Black. For one California journalist, anyone who was not a hostile Indian was assumed to be “white.”[12]Susan M. Colby, Sacagawea’s Child: The Life and Times of Jean-Baptiste Charbonneau (Spokane, Washington: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 2005), 165. Native Americans, on the other hand—at least those who were being displaced from their homelands—were neither trusted nor welcome.

The three mountain men arrived separately over as much as a two-year period. When Beckwourth arrived, Jean Baptiste had already established a boarding house or hotel—likely made of canvas:

Here [Murder’s Bar] I found my old friend Chapineau house-keeping, and staid with him until the rain season set in.”[13]The Autobiography of James P. Beckwourth as told to Thomas D. Bonner (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press: 1981), 509, archive.org/details/lifeadventuresof0000beck_u4a7.

William Dennison Bickham and his brother John were also mining at Murderer’s Bar in 1851. William wrote a journal of his time in California giving us a detailed look into the lives of those in the area. Of Jean Baptiste, he wrote:

Old Charbonneau is now with us on the bar and is as full of life and fun as any boy of 18. He can be heard laughing and making merry at any hour between breakfast time and midnight.[14]17 May 1851, A Buckeye in the Land of Gold: The Letters and Journal of William Dennison Bickham, Randall E. Ham, ed. (Spokane, Washington: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 1996), 159.

Bickham moved to San Francisco where he received letters from Jean Baptiste on 30 June and 29 August 1851.[15]Ibid., 183, 223. Unfortunately, the text of those letters have been lost to history, as is much of the life of Jean Baptiste Charbonneau during his California years.

Other Mentions

We do not know if Jean Baptiste ever made much money as a miner, but he was paid for a variety of other services in the Auburn area. The 1852 Placer County Treasurer’s Report, Schedule B lists a payment to “John Charbonneau services as Assistant Surveyor” for $48.00.[16]Angel, 143. He possibly worked for the Manhattan Bar, a large and lucrative mine in the area:

Manhattan Bar was a big mining camp, all on the Placer County side . . . . A Cherokee Indian, by name Sharaneau, lived there before telegraph times. He was used as a rapid dispatch bearer and runner . . . .[17]W. B. Lardner and M. J. Brock, History of Placer and Nevada Counties, California (Los Angeles: Historic Record Company, 1924), 178, archive.org/details/historyofplacern00lard.

Was “Sharaneau” our Jean Baptiste? This is plausible as he was a skilled horseman and in his prime the “best man on foot on the plains or in the Rocky Mountains.”[18]“The W. M. Boggs Manuscript About Bent’s Fort, Kit Carson, the Far West and Life Among the Indians” LeRoy R. Hafen, ed. The Colorado Magazine, 7 no. 2 (March 1930): 67, … Continue reading

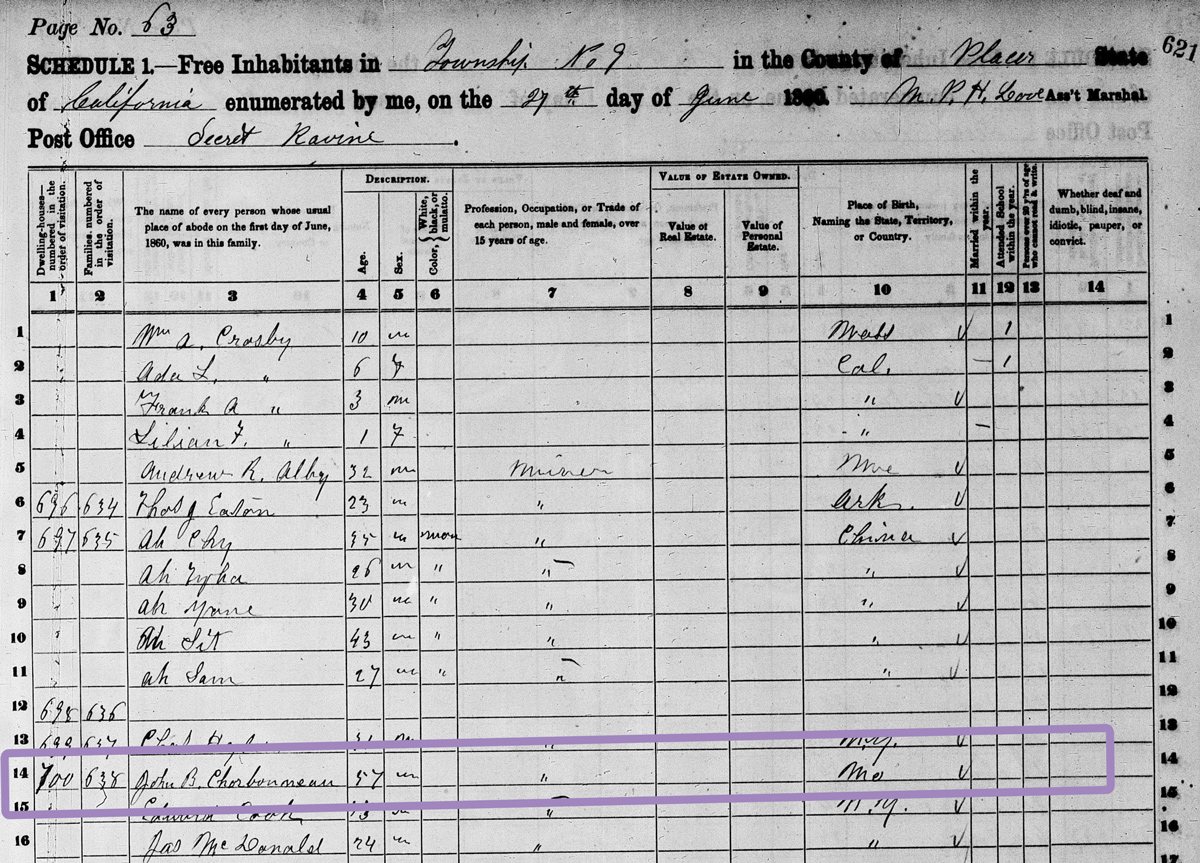

The 1860 U.S. Census lists Jean Baptiste as a miner living in one of the gulches surrounding Auburn:

- [Transcript] Page 63

- Schedule 1. Free Inhabitants in Township No. 9 in the County of Placer State of California enumerated by me, on the 27th day of June 1860. M. P. H. Love, Ass’t Marshal

- Post Office Secret Ravine.

- . . . . .

- [Name:] John B Chorbonneau

- Age: 57

- Sex: Male

- Color: White

- Profession: ” [miner]

- Place of Birth: MO

A year after the 1860 Census, the Placer County Directory has him as a clerk at the Orleans Hotel in Auburn.[19]Colby, 173.

“Old Charbonneau” remained in California longer than any other period of his life. He appears to have been a well-liked and popular character who found ways to keep his hands off the shovels, picks, and pans and his feet out of the cold river water. In 1866, he decided to leave for Montana in what became his final journey.

Notes

| ↑1 | William H. Emory, Notes of a Military Reconnaissance, from Fort Leavenworth, in Missouri, to San Diego (Washington: Wendell and Van Benthuysen, Printers, 1848), 116, archive.org/details/notesamilitaryr01emorgoog/. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | R.B. Mason, U.S. Army Colonel and California Governor, 2 August 1847 in Zephyrin Englehardt, San Luis Rey Mission (San Francisco: The James H. Barry Company, 1921), 145–46, archive.org/details/sanluisreymissio0000enge; Hubert Howe Bancroft, History of California (San Francisco: The History Company, 1886), 5:621n1. |

| ↑3 | Dane Bevan, “From Jean Baptiste Charbonneau,” Oregon History Project, www.oregonhistoryproject.org/articles/historical-records/from-jean-baptiste-charbonneau/ accessed 9 June 2023. |

| ↑4 | Irving W. Anderson, “J. B. Charbonneau, Son of Sacajawea,” Oregon Historical Quarterly, 71, no. 3 (Sep., 1970): 260, www.jstor.org/stable/20613180. |

| ↑5 | Bancroft, 5:568. |

| ↑6 | Englehardt, 147–151. |

| ↑7 | “J.F. Stevenson to Gov. Mason,” July 24, 1848, in Ann W. Hafen, French Fur Traders and Voyageurs in the American West, LeRoy R. Hafen, ed. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1993), 91; Albert Furtwangler, “Sacagawea’s Son as a Symbol,” Oregon Historical Quarterly 102, no. 3 (2001): n44, www.jstor.org/stable/20615158. |

| ↑8 | In a letter written by Jean Baptiste, Ann Hafen provides: “I am prepared to prove that the Indian Paulino is guilty of what he has sworn to my charge, and I will prove in the trial that he has taken a false oath.” This is another example of the “hassles” encountered by Jean Baptiste as Alcalde, but the context of this letter needs further research. Ann Hafen, p. 91 citing the Bandini papers in the San Diego Archives. |

| ↑9 | Art Sommers, John Knox, and April McDonald-Loomis, Images of America: Early Auburn (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2015), 35, 38, 75. |

| ↑10 | Legally named Beckwith, James Pierson Beckwourth (1798/1800–1566) had been born into slavery in Virginia. He became a free man of multiracial decent and worked as a fur trapper, explorer, scout, and various other occupations. |

| ↑11 | Myron Angel, ed. History of Placer County, California . . . (Oakland: Thompson & West, 1882), 68–71, www.archive.org/details/historyofplacerc00ange. |

| ↑12 | Susan M. Colby, Sacagawea’s Child: The Life and Times of Jean-Baptiste Charbonneau (Spokane, Washington: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 2005), 165. |

| ↑13 | The Autobiography of James P. Beckwourth as told to Thomas D. Bonner (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press: 1981), 509, archive.org/details/lifeadventuresof0000beck_u4a7. |

| ↑14 | 17 May 1851, A Buckeye in the Land of Gold: The Letters and Journal of William Dennison Bickham, Randall E. Ham, ed. (Spokane, Washington: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 1996), 159. |

| ↑15 | Ibid., 183, 223. |

| ↑16 | Angel, 143. |

| ↑17 | W. B. Lardner and M. J. Brock, History of Placer and Nevada Counties, California (Los Angeles: Historic Record Company, 1924), 178, archive.org/details/historyofplacern00lard. |

| ↑18 | “The W. M. Boggs Manuscript About Bent’s Fort, Kit Carson, the Far West and Life Among the Indians” LeRoy R. Hafen, ed. The Colorado Magazine, 7 no. 2 (March 1930): 67, www.historycolorado.org/sites/default/files/media/document/2018/ColoradoMagazine_v7n2_March1930.pdf. For more on that period of his life, see Jean Baptiste, Mountain Man. |

| ↑19 | Colby, 173. |