1830: Return to the American Frontier

In late 1829, Jean Baptiste Charbonneau left Europe with Duke Paul Wilhelm of Württemberg and the two arrived in St. Louis on 1 December 1829.[1]See Jean Baptiste in Europe. From February to April 1830, Duke Paul traveled between Council Bluffs and Fort Clark and the Knife River Villages. By 18 July, Paul was at the foot of the Rocky Mountains.[2]Paul Wilhelm, Duke of Württemberg, Travels in North America 1822–1824, Savoie Lottinville, ed., trans. W. Robert Nitske (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1973), 472, … Continue reading Sometime during these American travels, Paul and Jean Baptiste had forever separated and the latter’s career as a mountain man began.

Craters of the Moon National Monument Inferno Cone

© July 2004 by Daniel Mayer. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.

In the summer of 1830, Warren Angus Ferris (1810–1873) recorded some of the movements of a fur brigade belonging to Robidoux, Drips, and Fontenelle[3]In 1830, Robidoux, Drips, and Fontenelle were working for the American Fur Company owned by John Jacob Astor and, at the time, the largest American business in the North American fur trade.Joseph … Continue reading in which Jean Baptiste is mentioned. Ferris was a Rocky Mountain trapper working in the Cache Valley and Snake River for the American Fur Company. He gave one of the first descriptions of the area now called Yellowstone National Park and created the “Map of the Northwest Fur Country.”

At the Rockies, Robidoux, Drips, and Fontenelle divided into three separate parties. A member of Robidoux’s group, J. H. Stevens, told Ferris—who had been traveling with Fontenelle—of suffering from heat and thirst while traveling through the sparse Craters of the Moon region. Various scattered groups made it to safety except for one greenhorn:

We spent that night and the following morning in the charitable office of conveying water to our enfeebled companions, who lingered behind, and the poor beasts that had been also left by the way, and succeeded in getting them all to camp, except the person and animals of Charbineau, one of our men, who could nowhere be found, and was supposed to have wandered from the trail and perished.[4]Warren Angus Ferris, Life in the Rocky Mountains: a diary of wanderings on the sources of the rivers Missouri, Columbia, and Colorado from February, 1830, to November, 1835, page 35, … Continue reading

Here begins seventeen years of infrequent references to Jean Baptiste—most with a unique spelling of his name—from some of the most notable mountain men of the era. Each gives a small piece of a larger puzzle, but none can give the full picture of Jean Baptiste as a fully grown adult in the Frontier West.

1832: Bridger’s Stolen Horses

At the 1832 Rendezvous at Pierre’s Hole, it appears Jean Baptiste was working as an independent trader in association with famed mountain man, Jim Bridger.

James Felix “Jim” Bridger (1804–1881) is one of the most popular and iconic representations of the Rocky Mountain fur trade era. He was one of the young men who answered William Ashley’s 1822 advertisement in the Missouri Republican.[5]For one of Ashley’s advertisements, see Lolos in the Fur Trade. He is said to be one of the two men who abandoned Hugh Glass—a story made famous in the 2015 movie The Revenant. He was also involved in the southwest trade, brought the first missionaries to the Pacific Northwest, supplied California and Oregon Trail emigrants from Fort Bridger, and guided several U.S. Army expeditions. He is also said to have extreme fluency in Plains Sign Language.[6]Cornelius M. Ismert, The Mountain Men, 6:85–104.

As recorded by Nathaniel Wyeth[7]In 1834, Wyeth was traveling with missionary Jason Lee, naturalists John Kirk Townsend and Thomas Nuttall, and William Sublette. Wyeth was forced to turn back due to a leg ailment that eventually led … Continue reading on 1 August 1832, fifteen Indians had seriously wounded one Bridger associate and stolen seven horses. It was Charbonneau who went after them:

Charboneau pursued them on foot but wet his gun in crossing a little stream and only snapped twice.[8]“The Correspondence and Journals of Captain Nathaniel J. Wyeth, 1831–6,” F. G. Young, ed. Sources of the History of Oregon, vol. 1 parts 3–6 (1899): 207–08, … Continue reading

Grand Tetons

© by Panoramio user NaturesFan1226. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license

“Teton Valley was known originally as Pierre’s Hole. Rich in beaver, it was a favorite stamping ground for British and American fur traders and trappers between 1819–1840.”

—Text of interpretive sign #139 on Idaho Highway 33.

1834: A Mock War Dance

William Marshall Anderson (1807–1881) was born into a prominent Virginia family that settled in Kentucky and Ohio and a second cousin to William Clark. While traveling with a fur-trading expedition in 1834, he kept a detailed journal. He first mentioned Jean Baptiste after the latter performed a war dance in Thomas Fitzpatrick’s[9]Thomas Fitzpatrick (1799–1854) was one of the first to answer the 1822 call of Andrew Henry and William Henry Ashley to trap in the Missouri River Rockies. He headed up the Missouri River in 1823 … Continue reading camp on Hams Fork in western Wyoming:

June 23, 1834—A Mock war dance was held also in Mr Fitzpatrick’s camp in compliment, I believe, to me. Baptiste Charboneau, a half breed, & born of the squaw mentioned by Clark & Lewis, on their journey, was the principal actor in this scene. Of him there is something whispered which makes him an object of much interest to me. At all events he is an intelligent and interesting young man. He converses fluently & well in English, reading & writing & speaking with ease French and German—understandg several of the Indian dialects—[10]The Rocky Mountain Journals of William Marshall Anderson: The West in 1834, Dale L. Morgan and Eleanor Towles Harris, ed. (San Marino, California: The Huntington Library, 1967), 142; Jason Lee wrote … Continue reading

This is but one of many stories of Jean Baptiste’s ability to hold a group’s attention—something that was likely also encouraged while traveling as an infant with the Lewis and Clark Expedition. By the end of that expedition’s return trip, he had become Clark’s “little danceing boy.”

1834: Earning Respect

In keeping with the expectations of a mountain man, Jean Baptiste showed that he was to be taken seriously. In the following scuffle, he likely gained the respect and approbation of his co-workers:

August 5, 1834—A stabbing match took place, which had like to have produced serious disturbances in both camps. Last night—horses were cut loose and halters were stolen, which led this morning to the charges and recriminations that produced the difficulty—Charbonneau accused a young white fellow whom he had discovered prowling about in the night with having committed the theft—for which compliment he was kind enough to offer Baptiste a flogging—not choosing it, and being somewhat liberally inclined he lent the accused his butcher-knife up to the hilt in the muscles of his shoulder—This is, per variety—[11]Anderson, 175.

1839: Skilled Hunter

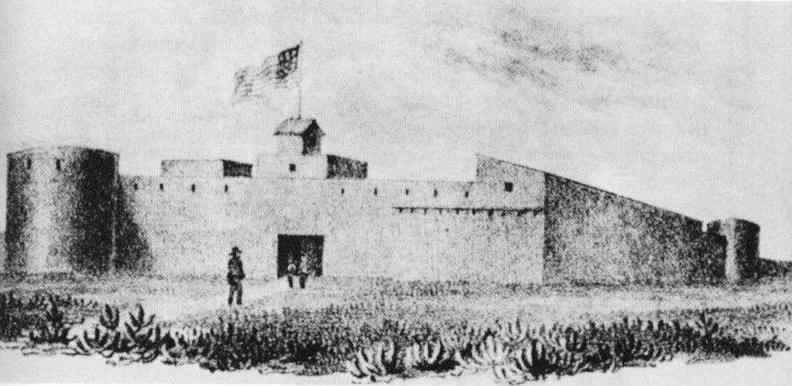

Pierre and the Buffalo

by Alfred Jacob Miller (1810–1874)

Commissioned by William T. Walters, 1858-1860, courtesy Walters Art Museum.

Although he did not die in the incident depicted above, the aptly nicknamed Unlucky Pierre would eventually be killed by a wounded buffalo.

Nothing is heard of Jean Baptiste between 1835 and 1838. During that time, resources tightened, and conflict followed. The two main American fur companies merged but were essentially run out by the Blackfeet Confederacy. The mountain men at the Rocky Mountain Rendezvous were being replaced by settlers, missionaries, and unscrupulous profiteers. Many trappers moved to the Southwest, and the buffalo hide trade increased as trade in beaver hides declined.

In 1839, Elias Willard Smith (1814/16–1886) traveled from St. Louis to the Rocky Mountains after graduating from the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.[12]After this trip, Smith had a long career as an architect and civil engineer. He found Jean Baptiste working as a hunter for Luis Vásquez and Andrew Sublette:[13]Pierre Louis Vasquez (1798–1868), also known as Luis Vásquez, was born and raised in St. Louis, the son of trader and explorer Benito Vásquez. Like Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, he was schooled at … Continue reading

August 6th, 1839.

. . . . .

The two gentlemen who had command of the party were old Indian traders, having followed this mode of life for more than ten years, there were also with us Mr. Thompson who had a trading post on the western side of the mountains, and two half breeds employed as hunters. One of them was a son of Captain Clarke, the great Western traveler and companion of Lewis. He had received an education in Europe during seven years.[14]J. Neilson Barry, “Journal of E. Willard Smith While with the Fur Traders, Vasquez and Sublette, in the Rocky Mountain Region, 1839–1840”, Oregon Historical Quarterly 14, no. 3 (Sep. … Continue reading

That Smith regards Jean Baptiste as William Clark’s son, reveals that many of those writing about him had only a vague understanding of his actual past. For Clark’s actual relationship with Jean Baptiste see Pompeys Pillar, An Offer to Raise Jean Baptiste, and Educating Jean Baptiste.

The record shows that Jean Baptiste was a skilled hunter. Sometime in June 1840, while coming down the Platte River, E. Willard Smith recalls “Shabenare” killing an American bison in a manner that seemed routine and easy:

This afternoon we had, as usual, tied up our boat and the hunter, Mr. Shabenare, went out a short distance from the river bank to shoot a buffalo for his meat. At the time there were several large buffalo bulls near us. After killing one we assisted the hunters in butchering it, and in carrying portions of the meat to the boat.

Smith then describes his own botched attempt to kill one. After wounding it, he escaped several close charges, ran out of powder, and finally resorted to his 6-inch butcher knife. He barely escaped being gored and trampled by the bull.[15]Smith, 277–79.

1842: “Helena” Island Host

South Fork Platte River

© 2014 by Jeffrey Beall. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license

In the summer of 1842, Jean Baptiste was charged by the Bent and St. Vrain Company[16]Charles Bent (1799–1847), brother William Bent (1809–1869) and Ceran St. Vrain (1802–1870) built what is now known as Bent’s Old Fort in southeastern Colorado. They had outlying posts and … Continue reading to take a load of furs from Bent’s Fort to St. Louis via the South Fork of the Platte River. While he waited on an island for higher water, visitors to his island camp witnessed him as a consummate host.

In July 1842, “The Great Pathfinder” John C. Frémont[17]John C. Frémont (1813–1890) was leading his first of five scientific and exploring expeditions in the American West when he met Jean Baptiste on “Helena Island.” His 1843 … Continue reading was greeted by Jean Baptiste who had a feast prepared that included coffee, sugar, and mint julips:

. . . arrived at Chabonard’s camp, on an island in the Platte . . . . Mr. Chabonard was in the service of Bent and St. Vrain’s company, and had left their fort some forty or fifty miles above, in the spring, with boats laden with the furs of the last year’s trade. He had met the same fortune as the voyageurs on the North fork, and, finding it impossible to proceed, had taken up his summer’s residence on this island, which he had named St. Helena . . . .

There was a large drove of horses in the opposite prairie bottom; smoke was rising from the scattered fires, and the encampment had quite a patriarchal air. Mr. C. received us hospitably. One of the people was sent to gather mint, with the aid of which he concocted very good julep; and some boiled buffalo toungue, and coffee with the luxury of sugar, were soon set before us. The people in his employ were genrally Spaniards, and among them I saw a young Spanish woman from Taos, whom I found to be Beckwith’s wife.[18]John C. Frémont, Report of the Exploring Expedition to the Rocky Mountains (Washington, D.C. Gales and Seaton, 1845), 30–31, archive.org/details/reportofexplorin00frem_1.

Beckwith had just married Luisa Sandoval from Santa Fe. Also known as James Pierson Beckwourth (1798/1800–1866), he had been born in Virginia most likely to an enslaved mother and her overseer. He became a free man and worked as a fur trapper, explorer, scout, and various other occupations. He was for a short time living with Jean Baptiste in the placer mines in California. In 1852, he established a hotel and store in Beckwith Valley, California and later ran the Denver store for Louis Vasquez. In 1864, he guided Chivington’s U.S. Cavalry troops to Sand Creek and witnessed the atrocities of the ensuing massacre there. He died while on a diplomatic mission to the Crows on behalf of the U.S. Military.[19]Delmont R. Oswald, The Mountain Men, 6:37–60.

Another Helena visitor that summer, journalist Rufus B. Sage, wrote of Jean Baptiste’s education and engaging personality:

Aug. 30th.

. . . . .

The camp was under the direction of a half-breed, named Chabonard, who proved to be a gentleman of superior information. He had acquired a classic education and could converse quite fluently in German, Spanish, French, and English, as well as several Indian languages. His mind, also, was well stored with choice reading, and enriched by extensive travel and observation. Having visited most of the important places, both in England, France, and Germany, he knew how to turn his experience to good advantage.

There was a quaint humor and shrewdness in his conversation, so garbed with intelligence and perspicuity, that he at once insinuated himself into the good graces of listeners, and commanded their admiration and respect.[20]Rufus B. Sage, Rocky Mountain Life; or, Startling Scenes and Perilous Adventures in the Far West, During an Expedition of Three Years (Boston: Wentworth & Company, 1857), 205–06, … Continue reading

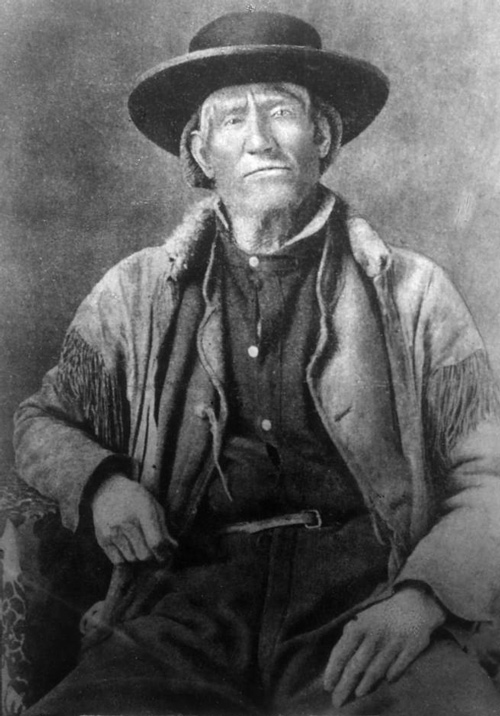

William Drummond Stewart (1844)

By Henry Inman (1801–1846)

Courtesy Missouri Historical Society. mohistory.org/collections/item/N38810.

1843: William Drummond Stewart’s Party

The adventure seeking Sir William Drummond Stewart (1795–1871) travelled throughout the American West in the 1830’s meeting many notable fur traders of the era. In 1837, he brought along American artist Alfred Jacob Miller whose paintings are among the first of the Rocky Mountain region.

Drummond’s last American adventure in 1843 was intended to be a pleasure trip. Along were many dignitaries of the era: William Sublette, William Clark’s son, step-son, and two nephews, Edmund Francis Xavier Chouteau, and Father Pierre-Jean De Smet.[21]Susan M. Colby, Sacagawea’s Child: The Life and Times of Jean-Baptiste (Pomp) Charbonneau (Spokane, Washington: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 2005), 151.

Sublette hired Jean Baptiste apparently as both a hunter and driver. As told by Kennerly Clark, they traveled with six men per cart—with each cart pulled by two mules. Kennerly, giving an oral history in his 90th year, recalled the following:

One of the drivers, Baptiste Charbonneau, was the son of an old trapper and Sacajawea . . . . I was recently asked . . . if Charbonneau spoke often of his mother and if he seemed to appreciate her fortitude and courage in making possible the discovery of an inland route to the great Pacific. I regret to say that he spoke more often of the mules he was driving and might have been heard early and late expatiating in not too complimentary a manner on their stubbornness.[22]William Clark Kennerly as told to Elizabeth Russell, Persimmon Hill: A Narrative of Old St. Louis and the Far West (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1948), 158, … Continue reading

1843: Settling Toussaint’s Affairs

Jean Baptiste likely left William Drummond Stewart’s party early and returned to St. Louis to settle his deceased father’s affairs. The following note, signed by Francis Pensoneau, comes from the Sublette Papers archive and reveals Toussaint Charbonneau had land that was sold during this time:

I promise to pay to J. B. Charbonno the Sum of Three hundred and twenty dollars, as soon as I dispose of land Claimed by him said Chabonno from the estate of his Deceased Father.” Signed by Francis Pensoneau at St. Louis on 14 August 1843.

The note is also signed by J. B. Charbonneau on 17 August: “To be paid W. A. [sic] Sublette.”[23]Sublette Papers, Missouri Historical Society cited in Anderson, 286.

The date of this note conflicts with the dates provided by Kennerly’s oral history that says during a fight between two others, Jean Baptiste “ran excitedly about, keeping a ring around the combatants with his heavy whip and shouting for no one to interfere.” According to Kennerly, the event happened near the time that the group left the plains for St. Louis on 17 August. Given the many years that passed before Kennerly recited his memories to his daughter, it is quite possible that he remembered the wrong date or person involved in this scuffle.[24]Clark, Persimmon Hill, 158.

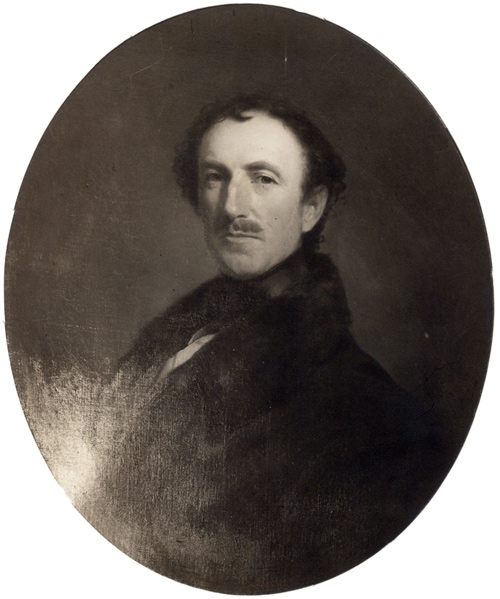

1844: Bent’s Fort Hunter

Bent’s Fort, 1845

From “Journal of Lieutenant J. S. Abert, from Bent’s fort to St. Louis, in 1845,” S. Doc. No. 438, 29th Cong., 1st Sess. (1846).

Jean Baptiste briefly met John James Abert—the illustrator of Bent’s Fort seen above—while the latter was at Bent’s Fort, but there is no record of Jean Baptiste working as his guide as some historians have stated. Abert’s journal shows that his guide during this time was Thomas Fitzpatrick. The hunter was long-time Fitzpatrick associate John Hatcher, and the Cheyenne interpreter was Bill Garey. There is no mention of Charbonneau nor is he listed in Abert’s “compliment” of personnel. Unfortunately, Ann Hafen attributed Abert’s high praise of Fitzpatrick to Jean Baptiste.[25]“Journal of Lieutenant J. S. Abert, from Bent’s fort to St. Louis, in 1845,” S. Doc. No. 438, 29th Cong., 1st Sess. (1846), 4–8; Ann W. Hafen, French Fur Traders and Voyageurs in … Continue reading

The 5 May and 6 June 1844 letters of Solomon Sublette[26]There were no less than five Sublette brothers involved in the Rocky Mountain fur trade. Solomon is the Sublette brother for whom the Sublette Cuttoff is named. He did not discover it, but likely … Continue reading indicate that he, “M S Vrain Ward & Shavano” were capturing live bighorn sheep and pronghorns to sell back east.[27]“A Fragmentary Journal of William L. Sublette,” Harrison C. Dale, ed., The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, vol. 6 (1 June 1919): https://archive.org/details/jstor-1886654. Ann Hafen asserts “some were taken successfully to St. Louis and some even to Sir William Drummond Stewart’s estate in Scotland.”[28]Ann Hafen, French Fur Traders, 88–89.

That winter, William M. Boggs, son of Missouri Governor Lilburn Boggs, was with a caravan traveling to Santa Fe. His recollections of that trip give one of the few glimpses of Jean Baptiste’s physical appearance:

He had been educated to some extent; he wore his hair long—that hung down to his shoulders. It was said that Charbenau was the best man on foot on the plains or in the Rocky Mountains.

Also of interest is Bogg’s description of “Tessou,” who had a close relationship with Jean Baptiste:

His father was French and his mother an Indian, but the writer was not informed of what tribe. “Tessou” was in some way related to Charbenau. Both of them were very high strung, but Tessou was quick and passionate. He fired a rifle across the court of the Fort at the head of the large negro blacksmith, only missing his skull about a quarter of an inch, because the negro had been in a party that chivaried Tessou the evening before, and being a dangerous man, Capt. St. Vrain gave him an outfit and sent him away from the Fort.[29]Boggs Manuscript, 67.

Citing Stella M. Drumm, Boggs editor Leroy Hafen speculates that Tessou and Jean Baptiste were half-brothers, that the former was the mysterious Toussaint Charbonneau, Jr. named in earlier documents. Most historians now believe Toussaint, Jr. and Jean Baptiste to be the same person. Toussaint Jusseaume—son of Lewis and Clark Expedition interpreter René Jusseaume and servant indentured to Meriwether Lewis—was educated in St. Louis at the same time as Jean Baptiste and is a possible candidate. Although several years older than Jean Baptiste, a strong bond between the two may have formed. Jusseaume the younger is but one possibility as there were many people around Bent’s Fort who could have been Tessou.

Jean Baptiste’s presence at Bent’s Fort and his years of experience made him a desired asset when the U.S. Army made their march to California in 1846. Jean Baptiste was hired as a hunter and guide for the Mormon Battalion, and he ended up living in California for many years.

Notes

| ↑1 | See Jean Baptiste in Europe. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Paul Wilhelm, Duke of Württemberg, Travels in North America 1822–1824, Savoie Lottinville, ed., trans. W. Robert Nitske (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1973), 472, archive.org/details/travelsinnortham0000paul. |

| ↑3 | In 1830, Robidoux, Drips, and Fontenelle were working for the American Fur Company owned by John Jacob Astor and, at the time, the largest American business in the North American fur trade. Joseph Robidoux, III (1783–1868) was an active trader in the early 1800’s, especially in the Council Bluffs area. He was a ruthless competitor to the Chouteaus and Manuel Lisa. Historian Merrill Mattes credits him for revitalizing the Santa Fe trade and by 1848, he had established St. Joseph which was a major jumping off point for the California gold fields. He died in St. Louis at the age of eighty-four. Dictionary of Missouri Biography, Lawrence O. Christensen, ed. (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1999), 653–55; Merrill J. Mattes, The Mountain Men and the Fur Trade of the Far West, Le Roy Hafen, ed. (Glendale, California: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 1969), 8:287–314. Andrew Drips (c. 1789–1860) held one of the longest tenures of any fur trader. In 1842, with the help of Pierre Chouteau, he was made a special Indian agent whose primary focus was to reduce the amount of liquor some traders were distributing. In 1848, he managed Fort Laramie before it was sold to the U.S. Government in 1849. Harvey L. Carter, The Mountain Men, 8:143–156. Lucien Fontenelle (1800–1840) worked for the Missouri Fur Company prior to it being bought out by the American Fur Company. He ran a fur trade post in present-day Bellevue, Nebraska. According to Warren Ferris, Fontenelle “assumed the direction of affairs” during the 1830 fur brigade. He continued in the trade until his death at age 39. Alan C. Trottman, The Mountain Men, 5:81–99. |

| ↑4 | Warren Angus Ferris, Life in the Rocky Mountains: a diary of wanderings on the sources of the rivers Missouri, Columbia, and Colorado from February, 1830, to November, 1835, page 35, user.xmission.com/~drudy/mtman/html/ferris/index.html. |

| ↑5 | For one of Ashley’s advertisements, see Lolos in the Fur Trade. |

| ↑6 | Cornelius M. Ismert, The Mountain Men, 6:85–104. |

| ↑7 | In 1834, Wyeth was traveling with missionary Jason Lee, naturalists John Kirk Townsend and Thomas Nuttall, and William Sublette. Wyeth was forced to turn back due to a leg ailment that eventually led to his death many years later. Nathaniel Jarvis Wyeth (1802–1856) had joined Kenneth McKenzie and William Sublette who were supplying the 1832 rendezvous in Pierre’s Hole. He continued west and tried to compete with the Hudson’s Bay Company by establishing Fort William just downriver from the latter company’s Fort Vancouver. His efforts to open Oregon to American trade failed, but his positive report of the Willamette River valley and use of the route through South Pass encouraged many settlers to go there. William R. Sampson, The Mountain Men, 5:381–401. Jason Lee (1803–1845) headed a small missionary party bound for the Salish Flatheads. He was escorted to Fort Vancouver by Nathaniel Wyeth and decided to instead build a mission in the Willamette Valley—the first Oregon Christian mission. |

| ↑8 | “The Correspondence and Journals of Captain Nathaniel J. Wyeth, 1831–6,” F. G. Young, ed. Sources of the History of Oregon, vol. 1 parts 3–6 (1899): 207–08, archive.org/details/correspondencejo00wyet. |

| ↑9 | Thomas Fitzpatrick (1799–1854) was one of the first to answer the 1822 call of Andrew Henry and William Henry Ashley to trap in the Missouri River Rockies. He headed up the Missouri River in 1823 and was involved with the fight with the Arikaras. He found early success trapping the Green River and in 1829 formed the Rocky Mountain Fur Company. He would become a guide to missionaries, pioneers, and U. S. Army exploring expeditions. In 1846, he was a guide to General Kearny who led the “Advanced Guard” ahead of Jean Baptiste Charbonneau and the Mormon Battalion. After that, he began to fulfill his duties as a successful Indian Agent. LeRoy R. and Ann W. Hafen, The Mountain Men, 7:87–102. |

| ↑10 | The Rocky Mountain Journals of William Marshall Anderson: The West in 1834, Dale L. Morgan and Eleanor Towles Harris, ed. (San Marino, California: The Huntington Library, 1967), 142; Jason Lee wrote a similar account of Charbonneau’s War Dance performance. |

| ↑11 | Anderson, 175. |

| ↑12 | After this trip, Smith had a long career as an architect and civil engineer. |

| ↑13 | Pierre Louis Vasquez (1798–1868), also known as Luis Vásquez, was born and raised in St. Louis, the son of trader and explorer Benito Vásquez. Like Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, he was schooled at “Bishop Dubourg’s College.” In late 1834, he and Andrew Sublette (1808–1853) partnered to trade on the South Platte. The next fall, they built Fort Vasquez at present-day Platteville, Colorado. William Clark issued them trading licenses in 1837 and 1838, but they failed to make any profit and sold the fort in 1840. After that, Vasquez partnered with Jim Bridger to trap and later run Fort Bridger. LeRoy R. Hafen, The Mountain Men, 2:321_338. |

| ↑14 | J. Neilson Barry, “Journal of E. Willard Smith While with the Fur Traders, Vasquez and Sublette, in the Rocky Mountain Region, 1839–1840”, Oregon Historical Quarterly 14, no. 3 (Sep. 1913): 253–53, www.jstor.org/stable/20609937. |

| ↑15 | Smith, 277–79. |

| ↑16 | Charles Bent (1799–1847), brother William Bent (1809–1869) and Ceran St. Vrain (1802–1870) built what is now known as Bent’s Old Fort in southeastern Colorado. They had outlying posts and stores in Santa Fe and Taos, New Mexico. The Bent brothers were the first to travel the Santa Fe Trail with a U.S. Army escort and oxen. In 1830, St. Vrain began working with the brothers and soon after became a partner. Prior, all three had become experienced fur trappers. William Bent often served the company as an “enforcer” among the Native Americans and Mexicans. During the U.S.-Mexican War, Charles Bent was appointed the first civil U.S. governor of New Mexico but was brutally killed four months later in the 19 January 1847 Mexican revolt in Taos. Keeping the fort running in the aftermath of the U.S.-Mexican War became difficult, and it is rumored that William emptied the fort and burned it. The actual facts are unclear. In 1853, William built “Bent’s New Fort” on the Arkansas River, hence the partially burned old fort remained in present Colorado and became known as Bent’s Old Fort. Between 1855 and 1870, St. Vrain lived in Mora, New Mexico where he was involved in several political and military campaigns including a short commission as a colonel in the Civil War. Harold H. Dunham, The Mountain Men, 2:27–48, 5:297–316; Samuel O. Arnold, The Mountain Men, 6:61–84. |

| ↑17 | John C. Frémont (1813–1890) was leading his first of five scientific and exploring expeditions in the American West when he met Jean Baptiste on “Helena Island.” His 1843 report—co-written with his wife Jesse—enticed many to immigrate along what became known as the Oregon Trail. He became a United States senator from California and the first Republican nominee for President of the United States. Steve Inskeep, Imperfect Union: How Jessie and John Frémont Mapped the West, Invented Celebrity, and Helped Cause the Civil War (New York: Penguin Press, 2020). |

| ↑18 | John C. Frémont, Report of the Exploring Expedition to the Rocky Mountains (Washington, D.C. Gales and Seaton, 1845), 30–31, archive.org/details/reportofexplorin00frem_1. |

| ↑19 | Delmont R. Oswald, The Mountain Men, 6:37–60. |

| ↑20 | Rufus B. Sage, Rocky Mountain Life; or, Startling Scenes and Perilous Adventures in the Far West, During an Expedition of Three Years (Boston: Wentworth & Company, 1857), 205–06, ia803103.us.archive.org/2/items/rockymountainlif00sagerich/rockymountainlif00sagerich.pdf. |

| ↑21 | Susan M. Colby, Sacagawea’s Child: The Life and Times of Jean-Baptiste (Pomp) Charbonneau (Spokane, Washington: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 2005), 151. |

| ↑22 | William Clark Kennerly as told to Elizabeth Russell, Persimmon Hill: A Narrative of Old St. Louis and the Far West (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1948), 158, babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015008151444&view=1up&seq=6; also in similar form: “The W. M. Boggs Manuscript About Bent’s Fort, Kit Carson, the Far West and Life Among the Indians” LeRoy R. Hafen, ed. The Colorado Magazine, vol. 7 no. 2 (March 1930): 26–27, www.historycolorado.org/sites/default/files/media/document/2018/ColoradoMagazine_v7n2_March1930.pdf. |

| ↑23 | Sublette Papers, Missouri Historical Society cited in Anderson, 286. |

| ↑24 | Clark, Persimmon Hill, 158. |

| ↑25 | “Journal of Lieutenant J. S. Abert, from Bent’s fort to St. Louis, in 1845,” S. Doc. No. 438, 29th Cong., 1st Sess. (1846), 4–8; Ann W. Hafen, French Fur Traders and Voyageurs in the American West, LeRoy R. Hafen, ed. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1993), 89. |

| ↑26 | There were no less than five Sublette brothers involved in the Rocky Mountain fur trade. Solomon is the Sublette brother for whom the Sublette Cuttoff is named. He did not discover it, but likely traveled the shortcut on his way to California in 1845. The Beaver Plew Newsletter, The Museum of the Mountain Man, June 2023, p. 7. |

| ↑27 | “A Fragmentary Journal of William L. Sublette,” Harrison C. Dale, ed., The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, vol. 6 (1 June 1919): https://archive.org/details/jstor-1886654. |

| ↑28 | Ann Hafen, French Fur Traders, 88–89. |

| ↑29 | Boggs Manuscript, 67. |