Bitter Cherry, Prunus emarginata

Bitter Cherry Blossoms

Prunus emarginata

© 30 May 2008 by Walter Siegmund. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

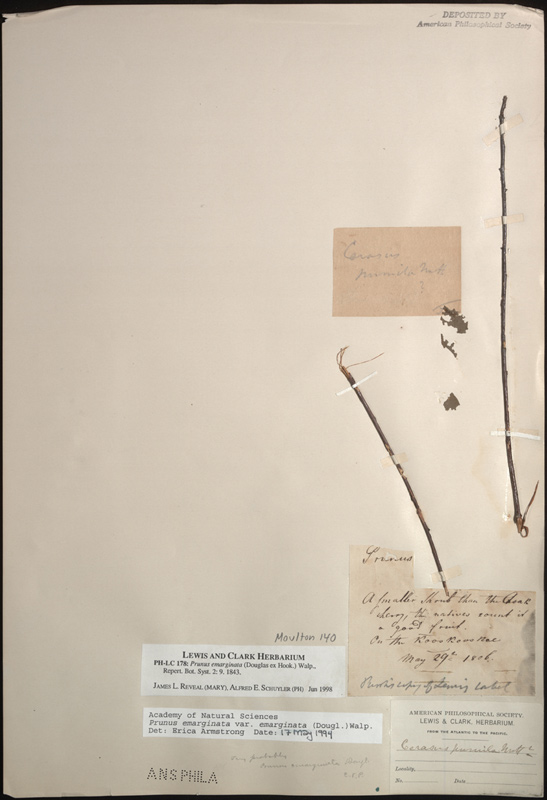

Housed at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia are the ‘moon rocks’[1]“In the case of the Lewis and Clark Herbarium, the specimens are icons. They are tangible links to a historical event; in fact they passed through the hands of Lewis, Clark, and Jefferson. They … Continue reading of the Lewis and Clark Expedition—the plant specimens collected in transit and preserved as the Lewis and Clark Herbarium. One specimen has only two small branches entirely stripped of leaves except for two small fragments taped separately to the sheet. Considering that the plant specimen had traveled by horse and dugout canoes from its bush near Long Camp in present-day Idaho to St. Louis, then shipped to President Thomas Jefferson, and finally stored and long forgotten at the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia, one can appreciate that it has survived at all. The specimen gives us a tangible reminder that Lewis saw, touched, smelled, and tasted a variety of cherry with important uses throughout the Salishan-speaking Peoples of the new Northwest.

A “Good Fruit”

Bitter Cherry Bark

© 30 May 2008 by Walter Siegmund. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

People of the Pacific Northwest utilized the bitter cherry’s red-tinted bark to create geometric patterns in their cedar bark baskets, a technique known as imbricating. The bark peels off in long thin strips which are strong and watertight, also useful for winding bows and making water tools such as harpoons, spears, fishing lines, and nets. Coastal Salish Tribes such as the Lower Chehalis, Tillamooks and Cowlitz used the strips to attach arrowheads to shafts. Interior Salish such as the Coeur d’Alenes would wind their bows with the bark. The wood was an excellent fuel and could be used as a fire starter with the friction method.[2]James Alexander Teit, “The Salishan Tribes of the Western Plateaus,” Forty-fifth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, Smithsonian Institution, 1927–1928 reprinted as Coeur … Continue reading

Bitter Cherry

© 26 June 2009 by Walter Siegmund. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Even though the bitter cherry did not taste as good as the common chokecherry, the Coeur d’Alene said they ate the fruit on occasion.[3]Teit, 54. Eighty-five miles north of Fort Clatsop, the Quinault used a decoction from the bark as a laxative, as did most other Coastal Tribes. Quinault women also used an infusion of rotten bitter cherry wood as a contraceptive.[4]Erna Gunther, Ethnobotany of Western Washington, revised edition (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1973), 37. A few more miles to the north, the Hoh made a blood medicine from a decoction of the bark.[5]Albert B. Reagan, “Plants Used by the Hoh and Quileute Indians,” Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science (1903-), 37 (Apr. 26–28, 1934): 64, www.jstor.org/stable/3625277. At the northwest terminus of the Olympic Peninsula, the Makah made a blood medicine, laxative, and tonic from the plant.[6]Daniel E. Moerman, Native American Ethnobotany (Portland, Oregon: Timber Press, 1988), 67. On Vancouver Island, the Saanich and Cowichan boiled the bark, often with crabapple bark, to make a tonic for colds. The Saanich also thought bathing their children in a concoction of bitter cherry and gooseberry roots would make them “intelligent and obedient.”[7]Turner, 87. The Bella Coola who resided at the terminus of Alexander Mackenzie’s Canada crossing, made a decoction of root and inner bark “boiled with much water” for use as a heart medicine.[8]Harlan I. Smith, “Materia Medica of the Bella Coola and Neighboring Tribes of British Columbia,” National Museum of Canada Bulletin no. 56, Annual Report for 1927, (1929): 58, … Continue reading

With so many uses, it should not be surprising that Lewis wrote on his bitter cherry’s specimen label “the natives count it a good fruit”.

Lewis’s Unrecognized Specimen

Lewis collected a specimen of bitter cherry, Prunus emarginata, while at Long Camp on 29 May 1806 and described it on 7 June 1806. The first notable botanists to review it—such as Frederick Pursh and Thomas Nuttall—failed to recognize it as a new species, inviting speculation that the sheet was not in good shape when it arrived in Philadelphia. Notations on the sheet have been added by later botanists and curators, and transcribed here:

Stamp: Deposited by American Philosophical Society

Handwritten Label:

Cerasus pumila Nutt.?

T. M [Thomas Meehan]

Handwritten Label:

Prunus

A smaller Shrub than the Choak cherry, the natives count it a good fruit.

On the Kooskooskee

May 29th 1806.

Pursh’s copy of Lewis’s label

Typewritten Label:

Academy of Natural Sciences

Prunus emarginata var. emarginata (Dougl.) Walp.

Det: Erica Armstrong Date: 17 May 1994

Handwritten Note: Very probably Prunus emarginata Dougl. C. V. P. [Piper]

Printed Label:

American Philosophical Society.

LEWIS & CLARK HERBARIUM.

FROM THE ATLANTIC TO THE PACIFIC.

Handwritten: Cerasus pumila Nutt?

[Locality, No., and Date left blank]

Perforation: ANS PHILA[9]The Definitive Journals of Lewis and Clark: Herbarium, Gary Moulton, ed., 46, Plate 140.

Lewis’s Botanical Description

Lewis correctly recognized P. emarginata as a new species of wild cherry, and accurately described it:

There is a speceis of cherry which grows in this neighbourhood in sitations like the Choke cherry or near the little rivulets and wartercouses. it seldom grows in clumps or from the same cluster of roots as the choke cherry dose. the stem is simple branching reather diffuse stem the cortex is of a redish dark brown and reather smooth. the leaf is of the ordinary dexture and colour of those of most cherries, it is petiolate; a long oval 1¼ inhes in length and ½ an inch in width, obtuse, margin so finely serrate that it is scarcely perseptable & smooth. the peduncle is common 1 inch in length, branch proceeding from the extremities as well as the sides of the branches, celindric gradually tapering; the secondary peduncles are about ½ an inch in length scattered tho’ proceeding more from the extremity of the common peduncle and are each furnished with a small bracted. the parts of fructification are much like those discribed of the choke cherry except that the petals are reather longer as is the calix reather deeper. the cherry appears to be half grown, the stone is begining to be hard and is in shape somewhat like that of the plumb; it appears that when ripe it would be as large as the Kentish cherry, which indeed the growth of the bush somewhat resembles; it rises about 6 or 8 feet high[10]Journals, 7:344.

Analysis of Botanical Terms

In his description of the bitter cherry, Lewis used fifteen botanical terms consistent with Benjamin Smith Barton‘s 1803 edition of Elements of Botany, one of the books historians call the “Traveling Library.” Most of Lewis’s botanical vocabulary words can also be found in John Miller’s translation of Linnaeus, a two-volume set also in the traveling library.[11]Stephen Dow Beckham, Doug Erickson, et al., The Literature of the Lewis and Clark Expedition: A Bibliography and Essays (Portland, Oregon: Lewis & Clark College, 2003), 47–48, 52–53. Barton also tutored Lewis at the request of President Thomas Jefferson.[12]See Jefferson’s letter to Barton in February 27, 1803. The following table provides insight into Lewis’s botanical sources and training. (Lewis’s alternate spellings are given in square brackets.)

| Term | Definition | Barton Count | Miller Count |

|---|---|---|---|

| bract | “furnished with bractes [bracts]” Barton 295 | 71 | 1 |

| calyx [calyx, calix] |

The group of outer leaves of the flower, Barton 107; Kew 24 | 193 | 270 |

| cortex | “Outer Bark” Barton 20; “bark or outer layer [antiquated term]” Kew 33 | 13 | 3 |

| cylindrical [cylindric, cilindric, cilindrical, celindrical] |

“formed into a cylinder, or equal tube” Barton 165 | 26 | 47 |

| diffuse [diffuse, defusely, defuse] |

“furnished with spreading branches” Barton 23 | 14 | 3 |

| fructification | “temporary part of vegetables, dedicated to the business of generation” Barton quoting Linnaeus, 106 | 67 | 23 |

| margin | “edge” Barton 33 | 21 | 0 |

| obtuse [obtuse, obtusely] |

“blunt” Barton 32 | 15 | 84 |

| oval [oval, ova] |

“round” Barton 193 | 4 | 16 |

| peduncle | “a partial stem, or trunk, which supports the fructification, without the leaves” Barton 71 | 51 | 21 |

| petiolate [petiolate, peteolate] |

“growing on a petiole or foot stalk” Barton 41; “with a leaf stalk” Kew 87 | 4 | 1 |

| scattered | “without any regular order” Barton 71 | 6 | 2 |

| serrate | “toothed like a saw” Barton 32 | 8 | 7 |

| simple branching | “does not divide” Barton 22 | 1 simple: 11 |

0 simple: 92 |

| smooth [smooth, smoth, mothe] |

“beardless” Barton 91; not rough or hairy, Kew 110 | 17 | 13 |

| tapering | “gradually narrowing” Kew 120; Barton 8 | 6 | 7 |

The above definitions come primarily from:

- Benjamin Smith Barton, Elements of Botany: or Outlines of the Natural History of Vegetables (Philadelphia: 1803), www.google.com/books/edition/Elements_of_Botany_Or_Outlines_of_the_Na/Hk0aAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0.

When appropriate, modern definitions have been given for additional clarity or when today’s definition has changed. The modern definitions come from:

- Henk Beentje, The Kew Plant Glossary: An Illustrated Dictionary of Plant Terms (Royal Botanic Gardens: Kew Publishing, 2012).

- James G. Harris and Melinda Woolf Harris, Plant Identification Terminology: An Illustrated Glossary (Spring Lake, Utah: Spring Lake Publishing, 2009).

- James L. Reveal, on this website in Camas. See also by Reveal, Lewis as Botanist.

When not enclosed with quotation marks, the definition has been paraphrased from the given source.

In the two columns of word counts, every effort has been made to count only those instances where the intended meaning is the one given in the definition. Alternate forms—for example, claw, claws, clawed—have been counted. Latin equivalents have been excluded from the count except when they are used exclusively by the author.

John Miller’s counts come from his two-volume translation:

- John Miller, An Illustration of the Sexual System, Of Linnaeus (London, 1779), books.google.com/books/about/An_Illustration_of_the_Sexual_System_Of.html?id=ak8-AAAAcAAJ.

- John Miller, An Illustration of the Termini Botanici of Linnaeus (London, 1789), archive.org/details/illustrationofse02mill.

Notes

| ↑1 | “In the case of the Lewis and Clark Herbarium, the specimens are icons. They are tangible links to a historical event; in fact they passed through the hands of Lewis, Clark, and Jefferson. They just happen to be very important scientifically, too. These are the “moon rocks” of Jefferson’s day, as one person put it.” (Volume 149 of the Proceedings of The Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, by Earle E. Spamer, introducing Reveal et al.’s taxonomic review of the Lewis and Clark plant collections (Special Publication 19). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | James Alexander Teit, “The Salishan Tribes of the Western Plateaus,” Forty-fifth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, Smithsonian Institution, 1927–1928 reprinted as Coeur d’Alene, Flathead and Okanogan Indians (Fairfield, Washington: Ye Galleon Press, 1985), 61, archive.org/details/coeurdaleneflath0000boas/; Nancy Chapman Turner and Marcus A. M. Bell, “The Ethnobotany of the Coast Salish Indians of Vancouver Island,” Economic Botany 25, no. 1 (1971): 87, www.jstor.org/stable/4253212. |

| ↑3 | Teit, 54. |

| ↑4 | Erna Gunther, Ethnobotany of Western Washington, revised edition (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1973), 37. |

| ↑5 | Albert B. Reagan, “Plants Used by the Hoh and Quileute Indians,” Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science (1903-), 37 (Apr. 26–28, 1934): 64, www.jstor.org/stable/3625277. |

| ↑6 | Daniel E. Moerman, Native American Ethnobotany (Portland, Oregon: Timber Press, 1988), 67. |

| ↑7 | Turner, 87. |

| ↑8 | Harlan I. Smith, “Materia Medica of the Bella Coola and Neighboring Tribes of British Columbia,” National Museum of Canada Bulletin no. 56, Annual Report for 1927, (1929): 58, geoscan.nrcan.gc.ca. |

| ↑9 | The Definitive Journals of Lewis and Clark: Herbarium, Gary Moulton, ed., 46, Plate 140. |

| ↑10 | Journals, 7:344. |

| ↑11 | Stephen Dow Beckham, Doug Erickson, et al., The Literature of the Lewis and Clark Expedition: A Bibliography and Essays (Portland, Oregon: Lewis & Clark College, 2003), 47–48, 52–53. |

| ↑12 | See Jefferson’s letter to Barton in February 27, 1803. |