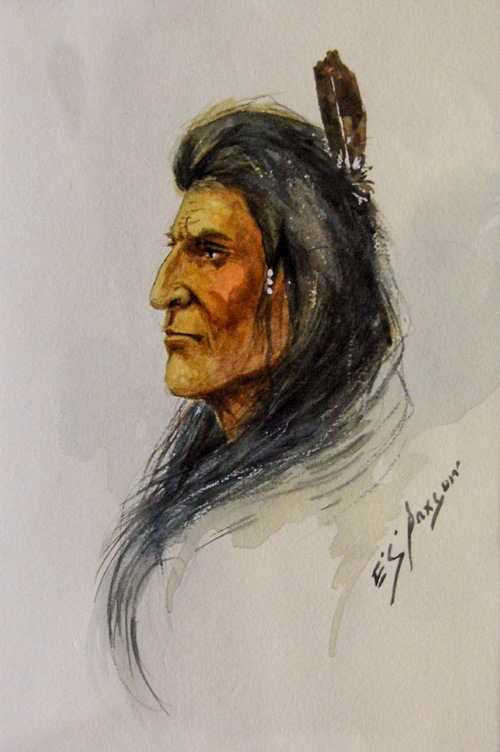

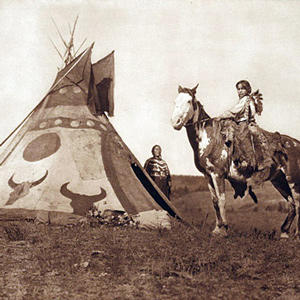

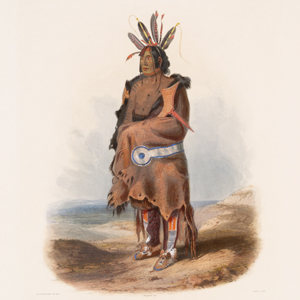

Cheyenne

Edgar S. Paxson (1852-1919)

Meloy & Paxson Galleries; The University of Montana PARTV Center.

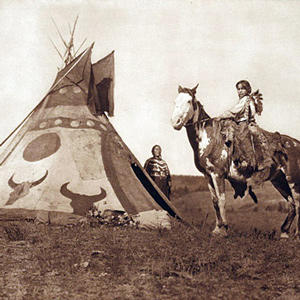

The expedition journalists spelled the people’s name Chyenne, Cheaun, Chion, and Chien. Originally, they lived along the Minnesota River. In 1680, a delegation traveled to La Salle’s Fort Crevecoeur in Illinois to invite the French to visit their lands. Later, the people migrated westward to avoid Sioux encroachment, and by the time of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, these Algonquian-speaking people lived on the Cheyenne River between the Missouri and Black Hills. The people had transitioned from gathering wild rice to horticultural and then, to a horse-based Plains culture subsisting primarily on buffalo.[1]John H. Moore, Margot P. Liberty, and A. Terry Straus, Handbook of North American Indians: Plains Vol. 15, ed. Raymond J. DeMallie (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1978), 863, 880.

Many, including the expedition members, misheard the people’s name as ‘chien’—French for ‘dog’. Their name actually comes from the Sioux exonym shahíyena, perhaps meaning ‘people of alien speech’. Their language was Algonquian, very different from the Siouan languages spoken by most of their neighbors.[2]Frederick Webb Hodge, Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico, Vol. 1 (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology, Government Printing Office, 1912), 250–251.

On their way up the Missouri River in 1804, the expedition passed an abandoned Cheyenne village and met only a handful of Cheyenne. One was Big Man, adopted by Hidatsa chief Le Borgne. Clark recorded what he and Lewis could learn about the people. The captains’ entry for the Cheyenne in their “Estimate of the Eastern Indians” written during the winter at Fort Mandan remains accurate:

They are the remnant of a nation once respectable in point of number: formerly resided on a branch of the Red river of Lake Winnipie [Winnipeg], which still bears their name [North Dakota’s Sheyenne River]. Being oppressed by the Sioux, they removed to the west side of the Missouri, about 15 miles below the mouth of the Warricunne creek, where they built and fortified a village, but being pursued by their ancient enemies the Sioux, they fled to the Black hills, about the head of the Chyenne river, where they wander in quest of the buffaloe, having no fixed residence. They do not cultivate. They are well disposed towards the whites, and might easily be induced to settle on the Missouri, if they could be assured of being protected from the Sioux. Their number annually diminishes. Their trade may be made valuable.[3]Moulton, Journals, 3:421.

Homeward-bound, the expedition met a large Cheyenne group at an Arikara village. The captains delayed to council with Mandan Chief Sheheke and various chiefs of the Arikara and Cheyenne. All but Sheheke declined the captains’ invitation to travel to Washington City, but one Cheyenne did ask the United States to establish trade with his people.

To maintain their hunting grounds, the Cheyenne continually fought with the Shoshones, Pawnees, and Crows. Around 1850, disruption from emigrant travel through their lands began diminishing the tribe, and many members died from cholera. On 29 November 1864, a peaceful tribe was massacred at Sand Creek, Colorado—the infamous Sand Creek Massacre.[4]Moore, et al., 863,865. Today, the Southern Cheyenne of Oklahoma and Northern Cheyenne of Montana constitute two federally recognized nations within the United States.[5]“Cheyenne,” Wikipedia accessed on 21 December 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cheyenne.

The Dog Soldiers are one of six Cheyenne military societies that formed in the mid-1800s. The Cheyenne fought may battles with the U.S. Army to preserve the Cheyenne way of life, and the Dog Soldiers remain especially popular in literature and film.

Selected Pages and Encounters

December 2, 1804

Cheyenne delegations

Fort Mandan, ND When four Cheyennes arrive, the captains give the standard diplomatic speech, gifts of tobacco, a flag, and demonstrations of many ‘curiosities.’ A letter of warning to the Sioux and Arikaras is also handed to the visitors.

Beginning with the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, the U.S. government set the vast area north of the Missouri (approximately 20 million acres) aside as the “Blackfeet Hunting Ground” for the Blackfeet and other tribes—Cree, Assiniboine, Gros Ventre, and Sioux.

October 30, 1804

Meeting Chief Sheheke

Ruptáre, second Mandan village, ND Indians not at yesterday’s council, including Chief Sheheke, arrive to see what they have missed. Clark and eight men head up the river in search of a place to build a fort for the winter.

December 1, 1804

Hudson's Bay Company visitor

Fort Mandan, ND George Henderson of the Hudson’s Bay Company visits, and Sgt. Ordway describes their business at the Knife River Indian villages. A delegation of Cheyennes and Arikaras arouse Mandan suspicions.

August 22, 1806

An engagé re-joins

Below Mobridge, SD The Arikara and Cheyenne chiefs decline Clark’s invitation to travel to Washington City. A Cheyenne chief asks that fur traders come to his nation, and a down-on-his-luck engagé from 1804 re-joins as they head down the Missouri River.

October 1, 1804

The Cheyenne River

Little Bend Rec. Area, SD Upon reaching the Cheyenne River, Lewis and Clark meet fur trader Jean Vallé who tells them about that river. They notice the ash tree leaves are turning color, and Lewis adds three plant specimens to the collection.

October 12, 1804

More Arikara diplomacy

Shaw Creek Rec. Area, SD The morning is spent parleying and trading with the Arikaras. At 1 pm, with the sounding horn and fiddle playing, the expedition heads up the Missouri River.

August 21, 1806

Arikara Villages

Above Mobridge, SD At the upper and lower Arikara villages, several councils are conducted between the Mandans, various Arikara chiefs, and visiting Cheyennes. The captains see Rivet, one of their 1804 engagés, who says a chief from an earlier Washington City delegation has died.

October 16, 1804

"Goat" hunting

Above Beaver Creek, ND The expedition struggles fourteen river miles passing countless sandbars. They see the Indians killing pronghorns, and the Indians make merry the greater part of the night. Elsewhere, the Hunter and Dunbar Expedition sets out.

Notes

| ↑1 | John H. Moore, Margot P. Liberty, and A. Terry Straus, Handbook of North American Indians: Plains Vol. 15, ed. Raymond J. DeMallie (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1978), 863, 880. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Frederick Webb Hodge, Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico, Vol. 1 (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology, Government Printing Office, 1912), 250–251. |

| ↑3 | Moulton, Journals, 3:421. |

| ↑4 | Moore, et al., 863,865. |

| ↑5 | “Cheyenne,” Wikipedia accessed on 21 December 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cheyenne. |