Today, Chinook often refers to the politically united Lower Chinook, Clatsops, Willapas, The Wahkiakums, and Kathlamets. To Lewis and Clark, the Chinooks were the people living on the north side of the Columbia River estuary. When Lewis and Clark met them, the people of Baker Bay had been trading with European ships for more than a decade.

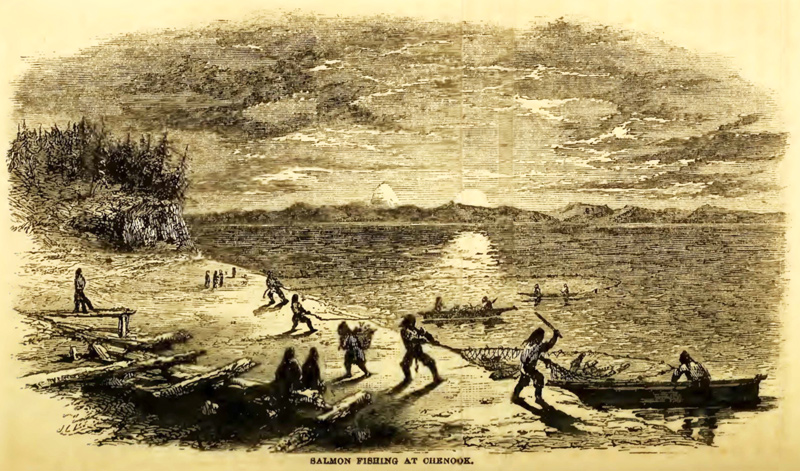

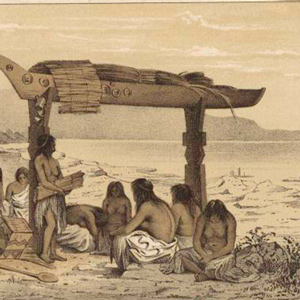

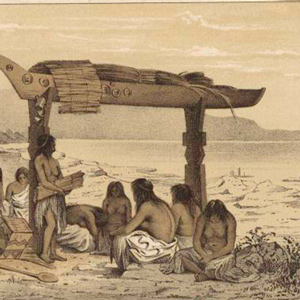

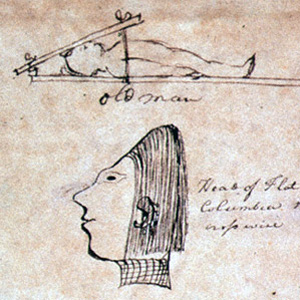

Salmon Fishing at Chenook

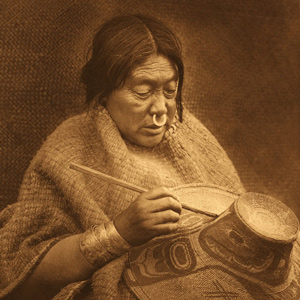

James Gilchrist Swan (1818–1900)

Engraving from a sketch by James G. Swan. From Three Years’ in Residence Territory, pages 105–6.

Ethnographer James G. Swan arrived at Willapa Bay, then called Shoalwater, in 1852 and lived among the Chehalis and Chinook as an oyster farmer. Later, he traveled extensively among the nations of the Northwest Coast, collected artifacts for the Smithsonian Institution, and wrote the first monograph on the Makah people.[1]Wayne Suttles and Aldona Jonaitis, Handbook of North American Indians: Northwest Coast Vol. 7, ed. Wayne Suttles (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1990), 73.

The above illustration was included in his 1857 book, Three Years’ Residence in Washington Territory. He also painted the scene in words:

[A]t early dawn, we were aroused . . . . I went out and perched myself on a log that overlooked the busy scene. Looking up the river, almost in a line due east, Mount St. Helen’s reared its snowy head high in the region of the clouds. The rapidly increasing morning rendered it distinctly visible, although a hundred miles in the interior.

And now the whole population of the village was astir—white men and Indians, squaw, children, and dogs—all were awake and eager to enter upon the labors of the morning, and long before the sun was up all were intently engaged.[2]James G. Swan, The Northwest Coast; or, Three Years’ in Residence in Washington Territory (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1857), 103.

Swan also described in detail now the nets were made and the technique of seining for salmon. He ends the soliloquy on a melancholy note:

[T]he race of the Chenooks is nearly run. From a large and powerful tribe in the days of Comcomly [also known as Concomly], the one-eyed chief, they have dwindled down to about a hundred individuals, men, women, and children.[3]Swan, 108.

Gray’s First Contact

On 11 May 1792, Captain Robert Gray took the Columbia Rediviva over the Columbia River’s bar and sailed to a village that the Salishan-speaking Chehalis called cʼinúk (činúkʷ ). Gray had located the fabled Great River of the West, one of the missing legs of the Northwest Passage—the search for which motivated many explorers including the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

The ship’s logs provide the first written record of Chinookan Peoples. John Boit, a ship’s mate and brother-in-law of one of the Columbia Rediva‘s owners, wrote:

We directed our course up this noble River in search of a Village. The beach was lin’d with Natives, who ran along shore following the Ship. Soon after, above 20 Canoes came off, and brought a good lot of Furs, and Salmon, which last they sold two for a board Nail . . . . They appear’d to view the Ship with the greatest astonishment and no doubt we was the first civilized people that they ever saw . . . . At length we arriv’d opposite to a large village, situate on the North side of the River, about 5 leagues from the entrance . . . . We purchas’d 4 Otter Skins for a Sheet of Copper, Beaver Skins, 2 Spikes each, and other land furs, 1 Spike each.[4]John Boit, A New Log of the Columbia by John Boit on the Discovery of the Columbia River and Grays Harbor, ed. Edmond S. Meany (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1921), 3,31.

Gray and his crew found more than a river. They saw abundant wood to repair ships, fresh water to replenish empty kegs, plenty of salmon and wapato, and in Boit’s opinion “strait limb’d, fine looking fellows” and “pretty” women willing to trade. On leaving, Boit concluded “and so we go – thus, thus – and no War! -!”[5]Boit, 35.

Gray and his men were quick to spread the word, and with boosters like John Boit, many ships braved the river’s bar to trade with the Chinook. When George Vancouver sent Lieutenant Broughton over the bar in 1992, they found Captain Baker’s Jenny already anchored in what would be named Bakers Bay. Small wonder Lewis and Clark expected to find a trading ship at the mouth of the Columbia. Being there at the wrong season, they didn’t see any, but on 1 January 1806, Clark listed thirteen ships that the Chinook and Clatsop said visited regularly (see The Empty Anchorage).

“Great Higlers in Trade”

The Chinook were quick to establish themselves as the intermediaries between the European traders and the Chinookans living up the Columbia and Willamette rivers. During this period, salmon pemmican, wapato, and elk rawhide for making armor evolved from intense inter-Indian trade to major industries.

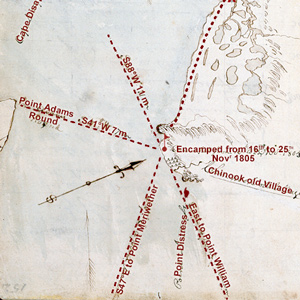

Archaeological evidence suggests that Chinookan peoples developed three major trading villages. Middle Village—the site where the expedition establish Station Camp on 15 November 1805—was primarily a trading post in response to European traders. The artifacts and buildings found there suggest the site was used more as a warehouse and staging area than a residence. The Clahclellah village at the Cascades of the Columbia—the expedition visited on 31 October 1805 and 9 April 1806—was a primary fishing site and controlled any trade items passing down the river. Cathlapotle—see November 5, 1805 and March 28, 1806—was a major factory of elk hides, or clamons, which were taken by ships to trade for sea otter skins with the Nootka and other peoples to the north. Clamon trade peaked between 1790 and 1810.[6]Yvonne Hajda and Elizabeth A. Sobel, Chinookan Peoples of the Lower Columbia, ed. Robert T. Boyd, et al. (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2013), 111–113.

The Chinook worked at retaining their position in the Columbia River trade. When the 1810 Winship Expedition bypassed cʼinúk to instead establish a post among the Skilloots, the Chinook harassed the builders convincing them to abandon the site. With the arrival of the Astorians in 1811, Middle Village was expanded and three of Concomly‘s daughters were married to traders there. By 1825, Concomly had become the most powerful chief other than perhaps Comowool of the Clatsop. The role of the Chinook would diminish with the establishment of Fort Vancouver and its inner coastal trade route via the Cowlitz River and Puget Sound. Never-the-less, Concomly’s daughter and ex-wife of Astorian Duncan McDougall would marry Kiesno (Casino) an influential chief among Chinookan Peoples and with the Hudson’s Bay Company at Fort Vancouver.[7]Michael Silverstein, Handbook . . ., 130, 541; Kenneth M. Ames, et al., Chinookan Peoples of the Lower Columbia, 134, 143,155–157.

Seeking Federal Recognition

In the mid–nineteenth century, the trading era diminished and new phases in United States–Indian relationships emerged. During each of these phases—treaties, removals, wars, land claims, assimilation, allotments, termination, and the modern Federal Acknowledgment Program—the first peoples of the Columbia River fared worse than most Native American peoples during this era. Not having federal recognition precludes the Chinook Tribe from having the rights, privileges, and sovereignty awarded to the majority of Native American Peoples.

On 5 August 1851, near a Clatsop village along a small creek that formed a small projection into the Columbia River estuary, the Clatsop signed a treaty negotiated with Oregon Territory Superintendent for Indian Affairs Anson Dart. The Nehalem Tillamooks signed a similar treaty the next day followed by treaties with the Chinooks and Cathlamets. Ten treaties were signed in all collectively known as the Tansy Point Treaties. A significant portion of lands would have been ceded, but the Chinook and Clatsop would have been allowed to live and fish in many of their traditional places. Many in Congress considered Dart’s treaties too generous towards the Indians and tabled them.

The Tansy Point treaties were never ratified nor rejected creating a legal morass which the Lower Chinook still are untangling. In 1855, confused and angry over the Tansy Point treaties, the people refused a treaty offered by Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens. Throughout the Oregon Territory, frustrations over the 1855 treaties led to the Puget and Plateau Indian wars. The lower Chinook remained peaceful. In 1864, the lands from the unratified treaties were taken by decree and the Chinook were asked to move to one of two small reservations in Chehalis and Shoalwater Bay. This led to legal land claims in the early 20th century, but the owners were awarded only .20 cents an acre for lands valued at $1.25 per acre.

The stress of coping with United States policies caused external rifts and internal splits. Dividing the territory into Oregon and Washington created artificial boundaries that divided the Chinookan peoples in ways that did not match their traditional system of families and villages further weakening their collective polity. In 1932, several ignored tribes were given allotments on the Quinault Reservation leaving the Quinault without any tribal land. As for the newcomers, they were not given voting rights. The Termination policies of the 1950s saw an inner split among the Chinook.[8]David G. Lewis, Chinookan Peoples, 320–321; Cesare Marino and Stephen Dow Beckham, Handbook . . ., 171,175, 181; “Making Treaties,” … Continue reading

In the 1970s, the Federal Acknowledgment program presented a new method of gaining federal recognition and the Chinook Tribe—consisting of the Lower Chinooks, Clatsops, Willapas, Wahkiakums and Kathlamets—were eager to take the path presented. Their claim was initially approved only to be reversed by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. The struggle for federal recognition continues to this day. [9]For more on seeking Federal recognition, see Andrew Fisher and Melinda Marie Jetté, Chinookan Peoples, Chapter 14.

Return to Tansy Point

The process of becoming a federally recognized tribe has had some positive outcomes: cultural revitalization, historical clarification, renewed relationships among internal divisions, and the resurgence of the Chinuk Wawa language with its new dictionary and higher education curriculum. In spring 2019, the Chinook Indian Nation purchased a 10-acre site at the Tansy Point Treaty Grounds. At the time of this writing, they have raised nearly enough money to add a structure for cultural and community gatherings, erect an interpretive kiosk, and restore the rest of the site’s habitat to its natural state.[10]“Preserve Tansy Point Treaty Grounds,” https://www.gofundme.com/f/preserve-tansy-point-treaty-grounds; Cindy Yingst, “Tribes show just how important Tansy Point is,” The … Continue reading

Selected Pages and Encounters

Concomly was a prominent Chinook citizen and leader whose people lived on the north side of the Columbia estuary, on the shore of Haley’s Bay. On November 17, 1805, he introduced himself to Lewis and Clark at Station Camp.

November 15, 1805

Moving to Station Camp

Station Camp near Chinook, WA The stormy weather finally breaks, and the main party paddles to Baker’s Bay, the end of their westward water journey. Camp is established near the Chinook’s Middle Village.

November 17, 1805

A disappointing cape

Station Camp near Chinook, WA Having explored Cape Disappointment, Lewis returns to Station Camp without finding any trading ships. Despite his report of a very bad road, several men volunteer to go there with Clark tomorrow.

November 18, 1805

The astonishing Pacific Ocean

Station Camp near Chinook, WA Clark takes a group to view the Pacific Ocean. On the way, they collect a California condor specimen and mark their names on trees. The men behold “with estonishment the high waves dashing against the rocks & this emence ocian.”

November 19, 1805

Exploring a long beach

Long Beach and Station Camp, WA Clark and his group continue over rugged hills from Cape Disappointment to present-day Long Beach, Washington. At Station Camp, one of the men trades his old razor for a Chinookan woven hat.

November 20, 1805

Sacagawea's belt of blue beads

Station Camp near Chinook, WA Clark’s party returns to Station Camp where they meet with Chiefs Concomly and Shelathwell. Another Indian trades two sea otter skins for Sacagawea’s belt of blue beads, and she is given a new coat.

November 21, 1805

Clatsop and Lower Chehalis visitors

Station Camp near Chinook, WA In addition to Clatsop and Lower Chehalis visitors, the wife of Chinook chief Delashelwilt brings young female camp followers. Clark describes the Chinooks.

November 22, 1805

A horrible day

Station Camp near Chinook, WA Clark calls it a horrible day as a storm blows in with high waves and tides forcing some to move their shelters and fires. Armbands and rings are used to buy wapato roots.

January 6, 1806

Sacagawea's plea

Fort Clatsop, Astoria, OR Sacagawea pleads to be permitted to see the beached whale, and her wish is “indulged.” Lewis describes the status of Chinookan women and laments the expedition’s paucity of trade goods.

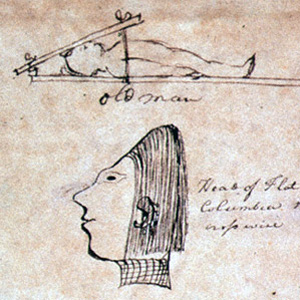

January 9, 1806

Canoe-style burials

Fort Clatsop and Necanicum Village, OR Clark’s party crosses Tillamook Head and returns to the salt works with whale oil and blubber. At Fort Clatsop, Lewis describes canoe burials and the language of the Chinookan Peoples.

January 13, 1806

Running out of candles

Fort Clatsop, Astoria, OR Elk tallow is rendered to make new candles, Lewis finds that the area’s elk do not have enough fat to make a sufficient supply, and President Jefferson writes to Lewis’s mother with news of the expedition’s progress.

January 15, 1806

Lewis's new fur coat

Fort Clatsop, Astoria, OR Lewis’s new fur coat is made from seven bobcat—and perhaps mountain beaver—robes purchased from the Indians. He describes Chinookan hunting methods and weaponry.

January 20, 1806

Five new plant specimens

Fort Clatsop, OR Lewis prepares five new plant specimens and describes roots eaten by local Indians. The captains worry about the rate at which they are going through their supply of elk meat.

January 27, 1806

An elk bonanza

Fort Clatsop, OR Shannon returns to Fort Clatsop with news of ten elk ready to be brought in. Lewis compares how he and the Chinookan Indians treat gonorrhea and syphilis.

February 18, 1806

Chinookan traders

Fort Clatsop, OR Chinookan traders arrive with woven hats and furs to sell. Whitehouse shows Clark his bobcat robe, and Ordway’s attempt to reach the salt works fails.

February 20, 1806

Cranberries for the sick

Fort Clatsop, OR Collins brings cranberries for the sick, and an important Chinook chief, Tahcum, visits for the first time.

March 1, 1806

Describing birds

Fort Clatsop, OR Lewis begins his treatise on bird species starting with the Columbian sharp-tailed grouse, new to science. He also writes about a Chinook slave and cattail roots.

March 18, 1806

Stealing a canoe

Fort Clatsop, OR After stealing a canoe, soldiers hide it near the fort. The captains write a short description of the expedition with the names of each member, and they distribute copies among the Indians.

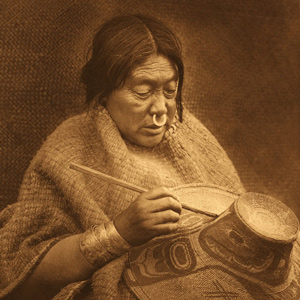

The most remarkable trait in the Clatsop Indian physiognomy, Lewis wrote on 19 March 1806, was the flatness and width of their foreheads, which they artificially created by compressing the heads of their infants, particularly girls, between two boards.

March 23, 1806

Homeward bound

The dugouts are loaded, and they leave Fort Clatsop to begin their homeward-bound journey. Fighting high waves, they round Tongue Point and camp near the John Day River.

Notes

| ↑1 | Wayne Suttles and Aldona Jonaitis, Handbook of North American Indians: Northwest Coast Vol. 7, ed. Wayne Suttles (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1990), 73. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | James G. Swan, The Northwest Coast; or, Three Years’ in Residence in Washington Territory (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1857), 103. |

| ↑3 | Swan, 108. |

| ↑4 | John Boit, A New Log of the Columbia by John Boit on the Discovery of the Columbia River and Grays Harbor, ed. Edmond S. Meany (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1921), 3,31. |

| ↑5 | Boit, 35. |

| ↑6 | Yvonne Hajda and Elizabeth A. Sobel, Chinookan Peoples of the Lower Columbia, ed. Robert T. Boyd, et al. (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2013), 111–113. |

| ↑7 | Michael Silverstein, Handbook . . ., 130, 541; Kenneth M. Ames, et al., Chinookan Peoples of the Lower Columbia, 134, 143,155–157. |

| ↑8 | David G. Lewis, Chinookan Peoples, 320–321; Cesare Marino and Stephen Dow Beckham, Handbook . . ., 171,175, 181; “Making Treaties,” http://www.trailtribes.org/fortclatsop/making-treaties.htm, accessed on 25 February 2021. |

| ↑9 | For more on seeking Federal recognition, see Andrew Fisher and Melinda Marie Jetté, Chinookan Peoples, Chapter 14. |

| ↑10 | “Preserve Tansy Point Treaty Grounds,” https://www.gofundme.com/f/preserve-tansy-point-treaty-grounds; Cindy Yingst, “Tribes show just how important Tansy Point is,” The Columbia Press, 10 October 2019, https://thecolumbiapress.com/?a=1587+tribes-show-just-how-important-tansy-point-is; Edward Stratton, “Chinook Nation buys an Oregon foothold,” The Astorian, 17 May 2019, all accessed 26 Feb 2021. |