Sacagawea and Jean Baptiste

Carol Grende (1955–2009)

© 2009 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Because he was virtually tethered to his mother during most of the expedition, much of Jean Baptiste’s time on the expedition can be derived by following Sacagawea in the journals.

During his first nineteen months, Jean Baptiste Charbonneau was a passenger on the Lewis and Clark Expedition tagging along with his parents—Sacagawea and Toussaint Charbonneau—who were acting as interpreters.

The captains’ journals give a small glimpse into his experience. In the journals, he is called: “a fine boy,” “Shabonahs infant,” “Charbono’s Child,” “Charbono’s son,” “Pompy,” and “Baptiest.” Most often he is simply called “the child.” William Clark‘s “Pomp” and “little danceing boy Baptiest” come from Clark’s 20 August 1806 letter to Toussaint.[1]See Clark’s Offer to Raise Jean Baptiste. For his christening, see The Charbonneaus in St. Louis.

A Difficult Birth

On the day of his birth, 11 February 1805, two interpreters—René Jusseaume and Toussaint Charbonneau and their families—were living at Fort Mandan. Clark and several men were out on an extended hunting trip. Meriwether Lewis recorded the birth:

about five oclock this evening one of the wives of Charbono was delivered of a fine boy. it is worthy of remark that this was the first child which this woman had boarn and as is common in such cases her labour was tedious and the pain violent; Mr. Jessome informed me that he had freequently adminstered a small portion of the rattle of the rattle-snake, which he assured me had never failed to produce the desired effect, that of hastening the birth of the child; having the rattle of a snake by me I gave it to him and he administered two rings of it to the woman broken in small pieces with the fingers and added to a small quantity of water. Whether this medicine was truly the cause or not I shall not undertake to determine, but I was informed that she had not taken it more than ten minutes before she brought forth[2]The Definitive Journals of Lewis & Clark, Gary Moulton, ed. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002), 3:291.

An Addition to Our Number

In his summary of an extended hunting trip, Sgt. Patrick Gass wrote:

On the 12th [12 February 1805] we arrived at the fort; and found that one of our interpreter’s wives had in our absence made an addition to our number.[3]Journals, 10:72.

This would be the only mention of Jean Baptiste in the enlisted men‘s journals.

Leaving Fort Mandan

When the thirty-three people—called the permanent party—left Fort Mandan bound for the Pacific Ocean, Clark includes Jean Baptiste in his list of personnel:

our party consisting of Sergt. Nathaniel Pryor Sgt. John Ordway Sgt. Pat: Gass, William Bratten, John Colter Joseph & Reubin Fields, John Shields George Gibson George Shannon, John Potts, John Collins, Jos: Whitehouse, Richard Windser, Alexander Willard, Hugh Hall, Silas Gutrich, Robert Frazure, Peter Crouzat, John Baptiest la page, Francis Labich, Hugh McNeal, William Werner, Thomas P. Howard, Peter Wiser, J. B. Thompson and my Servent york, George Drewyer who acts as a hunter & interpreter, Shabonah and his Indian Squar to act as an Interpreter & interpretress for the snake Indians—one Mandan & Shabonahs infant. Sah-kah-gar we â[4]Journals, 4:11.

The same day, 7 April 1805, Lewis describes the sleeping and cooking arrangements. The Charbonneau family would sleep with the captains in Toussaint Charbonneau’s buffalo hide teepee:

Capt. Clark myself the two Interpretters and the woman and child sleep in a tent of dressed skins. this tent is in the Indian stile, formed of a number of dressed Buffaloe skins sewed together with sniues [sinews]. it is cut in such manner that when foalded double it forms the quarter of a circle, and is left open at one side where it may be attached or loosened at pleasure by strings which are sewed to its sides to the purpose. to erect this tent, a parsel of ten or twelve poles are provided, fore or five of which are attatched together at one end, they are then elivated and their lower extremities are spread in a circular manner to a width proportionate to the demention of the lodge, in the same position orther poles are leant against those, and the leather is then thrown over them forming a conic figure.—[5]Journals, 4:10.

Here, the second interpreter was George Drouillard, who was also the lead hunter. The group formed its own “mess” separate from the three enlisted men, and Sacagawea and/or Charbonneau were likely the primary cooks.

Walking the Shore

As the boats pushed their way up the Missouri River’s northern reach, one of the captains typically walked the shore. On 18 April 1805, near present-day Lewis and Clark State Park in North Dakota, Charbonneau had taken a purgative, and would need to make frequent stops. For this reason, his and his family joined Clark on shore:

after brackfast I assended a hill and observed that the river made a great bend to the South, I concluded to walk thro’ the point about 2 miles and take Shabono, with me, he had taken a dost of Salts &c. his Squar followed on with his child, when I Struck the next bend of the [river] could See nothing of the Party, left this man & his wife & Child on the river bank and went out to hunt[6]Journals, 4:52.

A Flash Flood

Breathless Moment

Charles M. Russell (1903), for Olin D. Wheeler, The Trail of Lewis and Clark. See also Wheeler’s “Trail of Lewis and Clark”.

During the portage at the Falls of the Missouri, the Charbonneaus were the last to leave the lower portage camp. On their trip to the White Bear Islands[7]See The Portage Route. on 29 June 1805, Jean Baptiste nearly lost his life in a flash flood, here described by Clark:

I deturmined my Self to proceed on to the falls and take the river, according we all Set out, I took my Servent [York] & one man Chabono our Interpreter & his Squar accompanied, Soon after I arrived at the falls, I perceived a Cloud which appeared black and threaten imediate rain, I looked out for a Shelter but Could See no place without being in great danger of being blown into the river if the wind Should prove as turbelant as it is at Some times about ¼ of a mile above the falls I obsd a Deep rivein in which was Shelveing rocks under which we took Shelter near the river and placed our guns the Compass &c. &c. under a Shelveing rock on the upper Side of the Creek, in a place which was verry Secure from rain, the first Shower was moderate accompanied with a violent wind, the effects of which we did not feel, Soon after a torrent of rain and hail fell more violent than ever I Saw before, the rain fell like one voley of water falling from the heavens and gave us time only to get out of the way of a torrent of water which was Poreing down the hill in the rivin with emence force tareing every thing before it takeing with it large rocks & mud, I took my gun & Shot pouch in my left hand, and with the right Scrambled up the hill pushing the Interpreters wife (who had her Child in her arms) before me, the Interpreter himself makeing attempts to pull up his wife by the hand much Scared and nearly without motion— we at length retched the top of the hill Safe where I found my Servent in Serch of us greatly agitated, for our wellfar—. before I got out of the bottom of the revein which was a flat dry rock when I entered it, the water was up to my waste & wet my watch, I Scrcely got out before it raised 10 feet deep with a torrent which turrouble to behold, and by the time I reached the top of the hill, at least 15 feet water, I directed the party to return to the Camp at the run as fast as possible to get to our lode where Clothes Could be got to Cover the Child whose Clothes were all lost, and the woman who was but just recovering from a Severe indispostion, and was wet and Cold, I was fearfull of a relaps I caused her as also the others of the party to take a little Spirits, which my Servent had in a Canteen, which revived verry much.[8]Journals, 4:342–43.

A Swollen Neck

Jean Baptiste’s illness while at Long Camp in May 1806 prompted nearly daily reports from his caregivers, the two captains. His illness has been diagnosed variously as mumps, tonsilitis with an infected lymph gland, an abscess, and mastoiditis. [Moulton, 22 May 1806, n3] Likely, the most effective cure of whatever was ailing Jean Baptiste was simply time.

22 May 1806

Charbono’s Child is very ill this evening; he is cuting teeth, and for several days past has had a violent lax, which having suddonly stoped he was attacked with a high fever and his neck and throat are much swolen this evening. we gave him a doze of creem of tartar and flour of sulpher and applyed a poltice of boiled onions to his neck as warm as he could well bear it.[9]Meriwether Lewis, Journals, 7:278. See also on this site Cream of Tarter.

23 May 1806

The Creem of tartar and sulpher operated several times on the child in the course of the last night, he is considerably better this morning, tho’ the swelling of the neck has abated but little; we still apply polices of onions which we renew frequently in the course of the day and night.[10]Meriwether Lewis, Journals, 7:280.

24 May 1806

The child was very wrestless last night; it’s jaw and the back of it’s neck are much more swolen than they were yesterday tho’ his fever has abated considerably. we gave it a doze of creem of tartar and applyed a fresh poltice of onions.[11]Meriwether Lewis, Journals, 7:282.

25 May 1806

the Child is more unwell than yesterday. we gave it a doze of creem of tartar which did not operate, we therefore gave it a clyster in the evening.[12]Meriwether Lewis, Journals, 7:284–5.For clyster see The Medical Supplies.

26 May 1806

The Clyster given the Child last evening operated very well. it is clear of fever this evening and is much better, the swelling is considerably abated and appears as if it would pass off without coming to a head. we still continue fresh poltices of onions to the swolen part.[13]Meriwether Lewis, Journals, 7:289.

27 May 1806

Charbono’s son is much better today, tho’ the swelling on the side of his neck I believe will terminate in an ugly imposthume a little below the ear.[14]Meriwether Lewis, Journals, 7:291.

28 May 1806

The Child is also better, he is free of fever, the imposthume is not so large but seems to be advancing to maturity.—[15]Meriwether Lewis, Journals, 7:297.

3 June 1806

Our invalids are all on the recovery; Bratton is much stronger and can walk about with considerable ease. the Indian Cheif appears to be gradually recovering the uce of his limbs, and the child is nearly well; the imposthume on his neck has in a great measure subsided and left a hard lump underneath his left ear; we still continue the application of the onion poltice.[16]Meriwether Lewis, Journals, 7:330–31.

5 June 1806

the child is recovering fast the inflamation has subsided intirely, we discontinued the poltice, and applyed a plaster of basilicon[17]See “Unguent Basillicon” in The Chemical Drugs.; the part is still considerably swolen and hard.[18]Meriwether Lewis, Journals, 7:334–35.

Dividing Forces

The Home Bound Routes

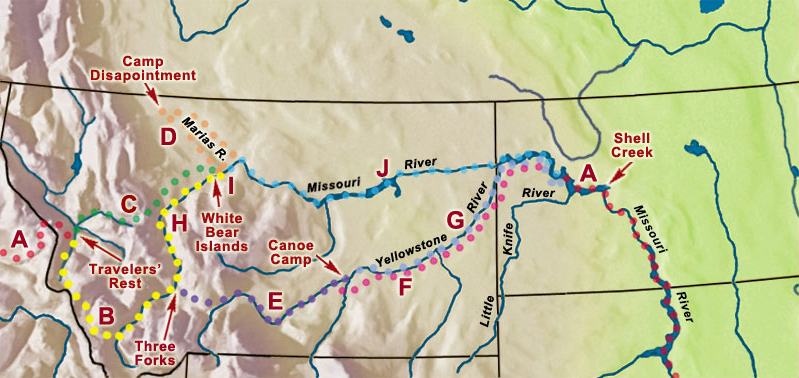

Travelers Rest to Reunion Bay

© 2000 VIAs Inc.

On the return journey, Jean Baptiste left Travelers Rest on 3 July 1806. As shown in points B, E, F, G, and A above, he traveled to Three Forks, over Bridger Pass, and down the Yellowstone River. See Dividing Forces at Travelers’ Rest.

To have interpreters for any Shoshone and Crow people they might meet, the Charbonneau family would travel down the Yellowstone River with Clark’s party:

we colected our horses and after brackfast I took My leave of Capt Lewis and the indians and at 8 A M Set out with [blank] men interpreter Shabono & his wife & child (as an interpreter & interpretess for the Crow Inds and the latter for the Shoshoni) with 50 horses.[19]William Clark, Journals, 8:161.

Pompy’s Tower

Pompeys Pillar National Monument

© 25 July 2017 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Stopping at a large rock below present-day Billings, Montana, Clark carved his name and the date into its face, and immortalized Jean Baptiste by naming the rock “Pompy’s Tower.”[20]Pompy, Janey, and Toby, nicknames given by Clark for Jean Baptiste, Sacagawea, and a Lemhi Shoshone guide, were also common slave names at the time. The possible significance of that is beyond the … Continue reading Early journal editor Nicholas Biddle mistakenly changed Clark’s original name to Pompey’s Pillar after the historic monolith in Rome. Later, the Geographic Names Information System (GNIS) removed the possessive apostrophe to be consistent with its naming standards. Pompeys Pillar is now a somewhat cryptic remnant of the person it was meant to honor.

Of the rock, Clark wrote on 25 July 1806:

This rock which I shall Call Pompy’s Tower is 200 feet high and 400 paces in secumphrance and only axcessable on one Side which is from the N. E the other parts of it being a perpendicular Clift of lightish Coloured gritty rock on the top there is a tolerable Soil of about 5 or 6 feet thick Covered with Short grass. The Indians have made 2 piles of Stone on the top of this Tower. The nativs have ingraved on the face of this rock the figures of animals &c. near which I marked my name and the day of the month & year.[21]Journals, 8:225.

Clark also named present-day Pompeys Pillar Creek, his first use of Baptiste:

this rock is Situated 250 paces from the water on the Stard Side of the river, and opposit to a large Brook on the Lard Side I call baptiests Creek[22]Journals, 8:224.

Tormented by Mosquitoes

In the “beaver bends” below the mouth of the Yellowstone, Lewis’s group was to rendezvous with Clark’s. Clark was waiting but had to move down the Missouri to escape the mosquitoes there. Everyone in his party suffered, but on 4 August 1806, Clark noted one particular casualty:

on this point the Musquetors were So abundant that we were tormented much worst than at the point. The Child of Shabono has been So much bitten by the Musquetor that his face is much puffed up & Swelled.

Parting Ways

The last mention of Jean Baptiste in the expedition journals came on 17 August 1806—the day the expedition left the Knife River Villages bound for St. Louis:

we also took our leave of T. Chabono, his Snake Indian wife and their Son Child who had accompanied us on our rout to the pacific Ocean in the Capacity of interpreter and interpretes. T. Chabono wished much to accompany us in the Said Capacity if we could have provailed the Menetarre [Hidatsa] Chiefs to dcend the river with us to the U. States, but as none of those chiefs of whoes language he was Conversent would accompany us, his Services were no longer of use to the U’ States and he was therefore discharged and paid up. we offered to convey him down to the Illinois if he Chose to go, he declined proceeding on at present, observing that he had no acquaintance or prospects of makeing a liveing below, and must continue to live in the way that he had done. I offered to take his little Son a butifull promising Child who is 19 months old to which they both himself & wife wer willing provided the Child had been weened. they observed that in one year the boy would be Sufficiently old to leave his mother & he would then take him to me if I would be so freindly as to raise the Child for him in Such a manner as I thought proper, to which I agreeed &c.—[23]William Clark, Journals, 8:305.

Clark amplified his offers in a letter written three days later (see Clark’s Offer to Raise Jean Baptiste). The family traveled to St. Louis in 1809 (see The Charbonneaus in St. Louis), and Jean Baptiste remained there under the guardianship of William Clark.

Notes

| ↑1 | See Clark’s Offer to Raise Jean Baptiste. For his christening, see The Charbonneaus in St. Louis. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The Definitive Journals of Lewis & Clark, Gary Moulton, ed. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002), 3:291. |

| ↑3 | Journals, 10:72. |

| ↑4 | Journals, 4:11. |

| ↑5 | Journals, 4:10. |

| ↑6 | Journals, 4:52. |

| ↑7 | See The Portage Route. |

| ↑8 | Journals, 4:342–43. |

| ↑9 | Meriwether Lewis, Journals, 7:278. See also on this site Cream of Tarter. |

| ↑10 | Meriwether Lewis, Journals, 7:280. |

| ↑11 | Meriwether Lewis, Journals, 7:282. |

| ↑12 | Meriwether Lewis, Journals, 7:284–5.For clyster see The Medical Supplies. |

| ↑13 | Meriwether Lewis, Journals, 7:289. |

| ↑14 | Meriwether Lewis, Journals, 7:291. |

| ↑15 | Meriwether Lewis, Journals, 7:297. |

| ↑16 | Meriwether Lewis, Journals, 7:330–31. |

| ↑17 | See “Unguent Basillicon” in The Chemical Drugs. |

| ↑18 | Meriwether Lewis, Journals, 7:334–35. |

| ↑19 | William Clark, Journals, 8:161. |

| ↑20 | Pompy, Janey, and Toby, nicknames given by Clark for Jean Baptiste, Sacagawea, and a Lemhi Shoshone guide, were also common slave names at the time. The possible significance of that is beyond the scope of this article. |

| ↑21 | Journals, 8:225. |

| ↑22 | Journals, 8:224. |

| ↑23 | William Clark, Journals, 8:305. |