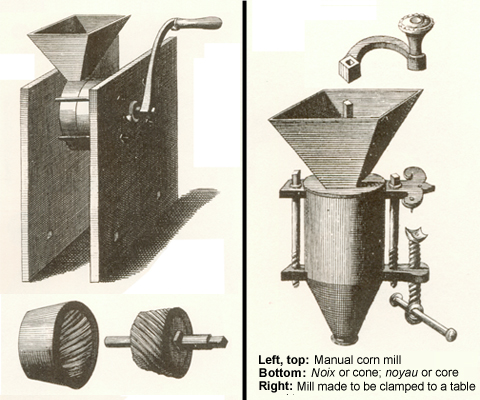

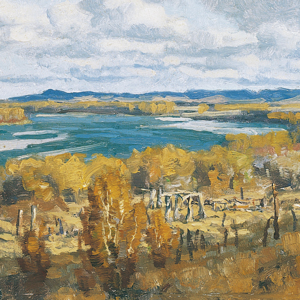

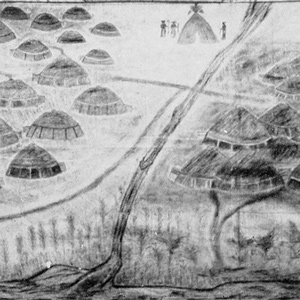

Mih-Tutta-Hangjusch, a Mandan village

Karl Bodmer (1809–1893)

Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library.[1]“Mih-Tutta-Hangkusch, Mandan Dorf. Mih-Tutta-Hangkusch, village Mandan. Mih-Tutta-Hangjusch, a Mandan village.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed 12 June 2019. … Continue reading

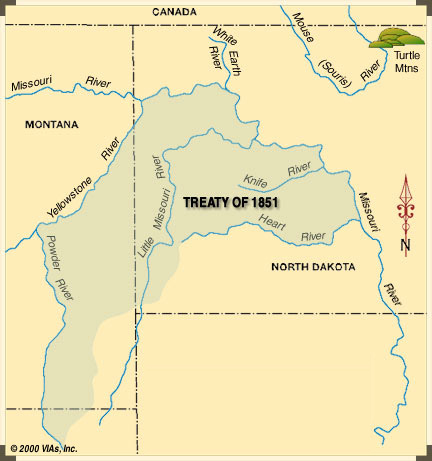

In the first record of European contact in 1738, La Vérendrye, reported nine villages of Mandan People living near the Heart River in present-day North Dakota.[2]Frederick Webb Hodge, Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico, Vol. 2 (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology, Government Printing Office, 1910), 797. When Lewis and Clark passed that river, they saw only the ruins of those villages. After the 1781 smallpox epidemic, the Mandan had moved into to a more defensible position in two villages immediately south of the Hidatsas at the Knife River. The Mandan-Hidatsa alliance had developed many years prior, and the two tribes previously shared their large hunting territory to the west.[3]W. Raymond Wood and Lee Irwin, Handbook of North American Indians: Plains Vol. 13, ed. Raymond J. DeMallie (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 2001), 349.

Prolific Traders

These Siouan-speaking people practiced horticulture and hunting in the manner of the Plains Village tradition. They were also prolific traders, exchanging their garden produce and acting as middlemen between European traders and other tribes including Assiniboines, Blackfeet, Crees, Crows, Pawnees, and—writes trader Pierre-Antoine Tabeau in one of his characteristic hyperboles—”an infinity of others.”[4]Pierre-Antoine Tabeau, Tabeau’s Narrative of Loisel’s Expedition to the Upper Missouri River, ed. Annie Heloise Abel, translated from French by Rose Abel Wright, (Norman: University of … Continue reading

When Lewis and Clark arrived in the fall of 1804, Mandan trade with Canadian-based commerce had long been established. For at least two decades European traders had intermarried and raised families in Mandan villages.[5]The Souris River route connected the Mandan villages with the English trading posts on the Assiniboine River. For more, see on this site, Souris River Trade Route. One notable trader living at the Knife River Villages, was Toussaint Charbonneau who joined the expedition as an interpreter and who more famously brought along his Lemhi Shoshone wife, Sacagawea.

Ceremonial and Religious Life

The Mandan people possessed a deep mythology and religious life. Lewis, Clark, and the others of the expedition glimpsed only a small portion, and understood even less.[6]For a fuller exploration into Mandan mythology and religion and the expedition members’ understandings of them, see Thomas P. Slaughter, Exploring Lewis and Clark: Reflections of Men and … Continue reading

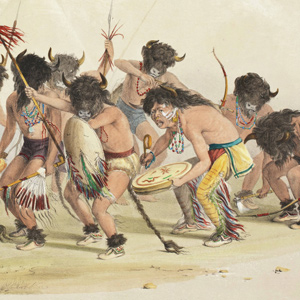

During the cold January days at Fort Mandan, the journalists tried to explain the Buffalo Dance and the Mandan practice of gaining power from elders by having them sleep with the younger man’s wife. On 5 January 1805, Clark says they sent one of the men to such a ceremony and that he was given four girls. On the 20th of that month, Patrick Gass and Joseph Whitehouse record a ritual of offering food to a buffalo head. Gass wrote, “Their superstitious credulity is so great, that they believe by using the head well the living buffaloe will come and that they will get a supply of meat.” Whitehouse also added:

The party who was at this Village also say that those Indians, possess very strange and uncommon Ideas of things in general, They are very Ignorant, and have no Ideas of our forms & customs, neither in regard to our Worship or the Deity &ca.

On 25 October 1804, Clark records the Mandan custom of cutting the first joint of a finger when mourning the loss of a relative. On 21 February 1805, the captains are told about the Mandan medicine stone, and on their return to St. Louis, Clark records the Mandan creation story (see 18 August 1806). Notably missing from the journalists accounts are personal and tribal bundles, the Okipa ceremony, Turtle Drums and a multitude of sacred beings.[7]The journalists’ role as ethnographers in the context of their stay at the Mandan villages is explored in James P. Ronda, Lewis and Clark among the Indians, Bison Book ed. (Lincoln: University … Continue reading

The Mythic Madoc Indians

In the years 1795–1797, James Mackay and John Evans explored the Missouri River between St. Louis and the Mandan Villages. Their supporter, the Spanish government, was eager to establish trade. Evans’s motivation was in search for the mythic Madoc Indians, but he also made maps. Traveling the same waterway in 1804, the captains continually confirmed the accuracy of the Evan’s maps and would not contribute significant geographic knowledge until after they left Fort Mandan on 7 April 1805.[8]For a comparison of Evans’ and Clark’s maps, see on this site, Clark’s Fort Mandan Maps.

Perhaps the Mandan people had difficulty understanding the Euro-American search for a North American tribe that was descended from Welsh Prince Madog—the mythic Madoc Indians. Jefferson specifically asked Lewis to look for such a tribe, and at the time of the expedition, the prime candidates were the Mandans. The people did have a genetic predisposition for premature graying, but little else to support the theory. The captains took a vocabulary of their language, but gave no opinion. The other journalists reporting hearing a brogue or seeing light complexions among various tribes they encountered. The Mandan connection may have faded away, but after his 1832 visit with the Mandan, artist George Catlin renewed the myth. Despite there being no solid archaeological, linguistic, or genetic evidence, many people today think the lost tribe has been, or will be, found.[9]Wood and Irwin, 350; Aaron Cobia, “Prince Madoc and the Welsh Indians: Was there a Mandan Connection?,” We Proceeded On, August 2011, Vol.37 No. 3, Page 16. Available at … Continue reading

After the Expedition

In 1837, the Mandans were nearly destroyed when the steamboat St. Peters brought smallpox to the Fort Clark village. In 1845, the Knife River Mandan and Hidatsa made a historic move to the Like-a-Fishook village, and the Fort Berthold trading post was soon built nearby. Years later, an American military post was added, and the Fort Berthold Reservation was established.

Today, the Mandan are part of the Three Affiliated Tribes also known as the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation. Stories of notable members can be viewed on the page Meet the Three Affiliated Tribes. For a geo-political analysis of traditional land holdings, see Fort Berthold Reservation.

Synonymy

This limited synonymy is meant to help the Lewis and Clark reader. Spellings from the journals are enclosed in brackets.[10]Moulton, Journals, 3:201n5 and 202, fig. 4. For a full synonymy, see Douglas R. Parks, Handbook of North American Indians: Plains Vol. 13, 362–64.

Mandan People: Mandane, Mantannes, Mantons, Mendanne, Mandanne, Mandians, Mandols

Mututahank village: [Matootonha, Ma-too-ton-ka, Mar-too-ton-ha], Mih-Tutta-Hangkusch, Métutahanke, Mitutahankish, Mitutanka, enumerated as First Mandan Village

Ruptáre village: [Roop-tar-hee, Roop-tar ha], Ruhpatare, Rùptari, Ruptadi, Nuptadi, Posecopsahe (Black Cat), East Village, enumerated as Second Mandan Village

Selected Pages and Encounters

Assessing the Legacy of Lewis and Clark

by Clay S. Jenkinson

The author proposes a few metaphors for the Lewis and Clark story, not in any definitive way, but merely to help us all think about the legacy of the expedition.

Too Né (Eagle Feather)

Arikara guide and diplomat

by Clay S. Jenkinson

This Arikara leader rode upriver with the expedition in the weeks that followed to negotiate a peace settlement with the Mandan. In the spring of 1805 he went down river with the barge to St. Louis. After a series of delays, he went to Washington, DC, to meet with President Jefferson.

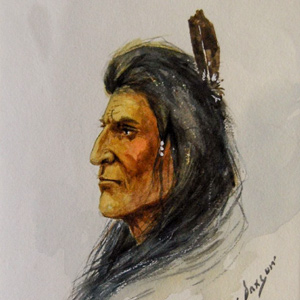

Posecopsahe (Black Cat)

In response to the captains’ requests for a Mandan-Arikara peace agreement, exclusive trade with St. Louis, and a Mandan delegation to visit Washington City, Posecopsahe initially gave favorable responses.

Sheheke and Yellow Corn

Sheheke and his wife, Yellow Corn, would visit Washington City at the request of the captains. It would be years before they could safely be returned to their people.

Meet the Three Affiliated Tribes

Interviews with tribal members

My name is Tex Hall. I’m the tribal chairman of the Three Affiliated Tribes . . . the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation . . . here at Fort Berthold at present day New Town, North Dakota. I would like to speak a little Hidatsa because I am Mandan and Hidatsa.

Hidatsa Territory

Becoming the Fort Berthold Reservation

After leaving Fort Mandan on 7 April 1805, the expedition traveled for several days through Hidatsa territory. Much of that area would become the Fort Berthold Reservation of the Three Affiliated Tribes, a coalition of Hidatsa, Mandan, and Arikara.

Flag Presentations

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Lewis and Clark usually distributed flags at councils with the chiefs and headmen of the tribes they encountered—one flag for each tribe or independent band.

Sheheke’s Delegation

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Sheheke’s diplomatic trip to Washington City and his difficult return home brought down the careers of at least two great leaders—himself, and Meriwether Lewis.

January 1, 1804

A new year at Wood River

At Wood River, Clark stages a shooting contest between local farmers and the enlisted men. He reports on two drunk soldiers and meets with a new washer woman. Both captains begin their weather diaries.

October 18, 1804

Passing the Cannonball

In passing the Cannonball River in present North Dakota, a ‘cannon ball’ is selected as a new anchor. Clark learns that most Arikaras avoid liquor, and Lewis adds prairie wild rose to his plant collection.

October 19, 1804

Gangs of buffalo

On their way to the mouth of the Little Heart River in present North Dakota, the expedition sees large herds of bison and elk, golden eagle nesting areas, and an abandoned Mandan village.

October 20, 1804

Pursuits and escapes

Below the Heart River Clark in present North Dakota, Clark sees On-a-Slant, a Mandan village abandoned due to Sioux attacks. Cruzatte wounds a grizzly and bison, and the unlucky hunter is chased by both.

October 24, 1804

Mandan cordiality

The morning brings snow and rain. Near present Washburn, North Dakota, the captains and Arikara chief Too Né are greeted by a Mandan chief and with great cordiality and ceremony, smoke the pipe.

October 25, 1804

Curious Mandans

The expedition continues up the Missouri River above present Washburn, North Dakota. Finding a good channel becomes difficult, and they hear news of Sioux and Assiniboine raids and a killing.

October 27, 1804

Ruptáre

At the second Mandan village—Ruptáre—they hire free trader René Jusseaume as an interpreter. They camp opposite Mahawaha, the Awaxawi Hidatsa village at the mouth of the Knife River.

The Knife River Villages

Marketplace

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Reaching the mouth of the Knife River on 27 October 1804, the expedition arrived in the midst of a major agricultural center and marketplace for a huge mid-continental region. The five permanent earth lodge communities there offered a panorama of contemporary Indian life.

October 28, 1804

Curiosity and corn

At camp across from the Knife River, Hidatsas and Mandans bring gifts of corn and curiosity about York. Posecopsahe (Black Cat), Clark, and Lewis look for a place to build winter quarters.

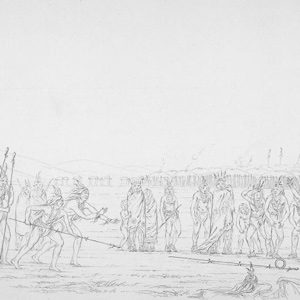

October 29, 1804

Mandan and Hidatsa council

Opposite the Knife River, Mandan and Hidatsa chiefs come from each village to council with the captains. A long speech is given, and the captains ask them to smoke the pipe of peace with an Arikara chief.

October 31, 1804

Black Cat speaks

Clark visits Posecopsahe (Black Cat), the main chief at Ruptáre, one of the five Knife River Villages. Posecopsahe wishes for peace and returns two beaver traps recently stolen from two French traders.

November 1, 1804

Looking for winter quarters

Lewis sends a letter and his British passport to a North West Company Fort and three Mandan chiefs visit. In the evening, Clark leaves to establish winter quarters and Lewis visits Mitutanka to get corn.

November 12, 1804

Mandan history lesson

Sheheke and his wife—likely Yellow Corn—visit the Fort Mandan construction site. She brings 100 pounds of meat, and he tells the Mandan creation story. He also describes the Hidatsa and Crow Nations.

November 18, 1804

Blackcat visits

At Fort Mandan, Black Cat’s wife brings as much corn as she can carry. Blackcat tells the captains that the Mandans have decided to continue with the Canada-based traders rather than St. Louis.

November 20, 1804

Sioux threats

At Fort Mandan below the Knife River Villages, Charbonneau brings in a large load of meat and furs, and the captains move into their quarters. Three chiefs from Ruptáre bring news of a Sioux threat.

November 22, 1804

Domestic violence

A Mandan man threatens to kill his wife for having slept with Sgt. Ordway. Clark orders the sergeant to give the man some trade goods. Twelve bushels of corn—still on the cob—is brought in.

November 27, 1804

Mandan deceptions

Lewis returns to Fort Mandan with two Hidatsa chiefs, and the captains learn that the Mandans have been telling lies to the Hidatsas. Seven Canada-based traders arrive at the Knife River Villages.

November 30, 1804

A military reprisal

Responding to news of a deadly Sioux and Arikara attack on Mandan hunters about 25 miles from Fort Mandan, Clark leads a military force to Mitutanka to gather warriors and pursue the attackers.

December 1, 1804

Hudson's Bay Company visitor

Trader George Henderson of the Hudson’s Bay Company visits Fort Mandan, and Sgt. Ordway describes their business at the Knife River villages. A delegation of Cheyennes and Arikaras arouse Mandan suspicion.

December 2, 1804

A Cheyenne delegation

When four Cheyennes arrive at Fort Mandan, the captains give them a speech, tobacco, a flag, and demonstrations of many ‘curiosities’. They also give them a letter of warning for the Sioux and Arikaras.

December 7, 1804

Hunting buffalo

A group of hunters joins with the Mandans, and Sgt. Gass is impressed with their buffalo hunting skills and well-trained horses. By day’s end, several suffer frostbite, and Clark issues half a gill of rum.

December 15, 1804

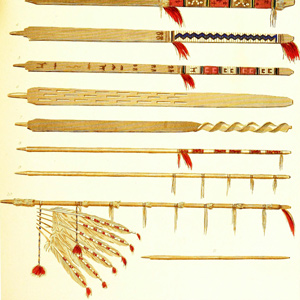

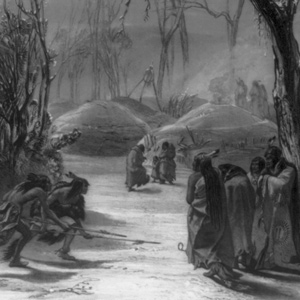

Tchung-kee

Sgt. Ordway and two others visit two Mandan villages to trade for corn. They see men playing Tchung-kee—a game involving rolling a stone and sliding sticks across a large ice field.

December 23, 1804

A Mandan treat

At Fort Mandan, Knife River villagers bring squash, corn, and beans. The wife of Little Raven cooks a Mandan treat for the captains while the enlisted men must deal with ‘large crowds’ in their quarters.

January 1, 1805

A new year at Fort Mandan

At Fort Mandan, New Year’s Day starts with rain and cannon fire. Several enlisted men are allowed to visit a nearby Mandan village, and Clark orders York to dance for them. The day ends snowy and cold.

January 4, 1805

Gifts for Little Raven

At Fort Mandan below the Knife River Villages, the weather warms enough to encourage hunters who kill a buffalo calf. Little Raven of Mitutanka visits and is given gifts, and the day ends cold and windy.

January 5, 1805

The Buffalo Dance

At Fort Mandan below the Knife River Villages, Clark works on his map of the west using information gathered from traders and Indians. He also describes the Mandan Nation’s Buffalo Dance ceremony.

January 15, 1805

Lunar eclipse

At Fort Mandan, celestial observations are made during a lunar eclipse. The captains receive their first Hidatsa visitors since November, and Pvt. Whitehouse is brought in to recover from frozen feet.

January 16, 1805

Hidatsa-Mandan jealousy

At Fort Mandan, the captains attempt to smooth over Hidatsa and Mandan jealousy. Lewis demonstrates the air gun and cannon, and the captains caution Seeing Snake not to war with the Shoshones.

January 23, 1805

Making sleds

At Fort Mandan below the Knife River Villages, the enlisted men awake to four inches of fresh snow and go about their ‘common’ day. Sleds are made and traded for locally grown beans and corn.

February 8, 1805

Wolves and Ravens

At Fort Mandan, Lewis entertains Posecopsahe (Black Cat) and his wife. Away from the Knife River Villages, Clark has a pen built to keep the wolves and ravens away from the harvest of the hunt.

February 16, 1805

Scorched earth

Many miles south of Fort Mandan and the Knife River Villages, Lewis and his soldiers continue their pursuit of a Sioux war party. They come to an old Mandan village where two lodges have been set afire.

February 20, 1805

Return to the old village

At Fort Mandan, Clark learns about the death an old Mandan man who is interned in a way that will return him to the “old village under ground.” Lewis’s group hunts its way back towards the fort.

February 21, 1805

Mandan Medicine Stone

At Fort Mandan, Big White and Big Man tell Clark that several Mandan men left the Knife River Villages to consult their Medicine Stone. Lewis’s hunting party returns with about 3,000 pounds of meat.

February 22, 1805

Fort Mandan rain

The residents of Fort Mandan receive their first rain since last November. Lewis and his recently returned hunters rest while the other enlisted men work to free the boats from the river’s snow and ice.

February 28, 1805

Arikara and Sioux news

Traders arrive at the Knife River Villages with news and two plant specimens for Lewis. About six miles from Fort Mandan, several enlisted men cut down cottonwood trees to make dugout canoes.

March 10, 1805

Hidatsa migration

Black Moccasin and another Hidatsa—likely White Buffalo Robe Unfolded visit Fort Mandan. They tell the captains how the Mandans and Hidatsas were decimated by wars and smallpox and then banded together.

March 16, 1805

Arikara bead-making

At Fort Mandan, trader Joseph Garreau shows the captains how the Arikara melt glass trade beads and then re-make them more to their liking. Pvt. Whitehouse strikes an Indian with his spoon.

March 20, 1805

Moving the dugout canoes

A few miles north of Fort Mandan, Clark and six men join a large group at the canoe camp where they move four dugout canoes to the river’s edge. Lewis discusses what we presently call Jerusalem artichokes.

March 23, 1805

A Hidatsa vocabulary

Fur trade clerks Charles McKenzie and François-Antoine Larocque end their visit at Fort Mandan in present North Dakota. A Hidatsa man helps the captains record a vocabulary of his language.

March 29, 1805

Burning the winter grass

At the Knife River Villages, the Indians’ ability to jump from one ice cake to another while pulling dead bison from the Missouri amazes Clark. They also burn the dead winter grass to promote new growth.

April 2, 1805

Preparing Clark's journals

Clark works all day and into the night preparing his journals so that they can be sent to Thomas Jefferson. Mandan Chief Raven Man ends his extended stay at Fort Mandan and returns to his village, Ruptáre.

April 5, 1805

Loading the small boats

The men load the red and white pirogues and six new dugout canoes. Sgt. Patrick Gass recalls the Indian sexual practices experienced during his stay at Fort Mandan amongst the Knife River Villages.

August 11, 1806

Cruzatte shoots Lewis

Lewis is shot through the buttock. An Indian attack is suspected, but likely Pvt. Cruzatte mistook him for an elk. Clark meets fur traders who share news of the barge, the fur trade, and Indian wars.

August 14, 1806

Among old friends

The expedition arrives at the Knife River Villages—one of which is the home of the Charbonneau family. The captains meet with various chiefs, and Clark invites them to travel to Washington City.

August 16, 1806

Parting gifts

At the Knife River Villages, a village gifts more corn than the boats can carry. A swivel gun is given to a Hidatsa chief and the blacksmith tools to Charbonneau. Sheheke agrees to go to Washington City.

August 18, 1806

A Mandan history lesson

Despite windy conditions, the expedition makes forty miles down the Missouri River. Chief Sheheke (Big White) tells Clark his people’s history. Near the Heart River, he tells the Mandan Creation Story.

August 21, 1806

At the Arikara villages

At the Arikara villages above present Mobridge, South Dakota, several councils are conducted between various Mandans, Arikaras, and Cheyennes. One of their 1804 engagés shares ominous news.

Notes

| ↑1 | “Mih-Tutta-Hangkusch, Mandan Dorf. Mih-Tutta-Hangkusch, village Mandan. Mih-Tutta-Hangjusch, a Mandan village.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed 12 June 2019. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-c441-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Frederick Webb Hodge, Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico, Vol. 2 (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology, Government Printing Office, 1910), 797. |

| ↑3 | W. Raymond Wood and Lee Irwin, Handbook of North American Indians: Plains Vol. 13, ed. Raymond J. DeMallie (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 2001), 349. |

| ↑4 | Pierre-Antoine Tabeau, Tabeau’s Narrative of Loisel’s Expedition to the Upper Missouri River, ed. Annie Heloise Abel, translated from French by Rose Abel Wright, (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1939), 161. |

| ↑5 | The Souris River route connected the Mandan villages with the English trading posts on the Assiniboine River. For more, see on this site, Souris River Trade Route. |

| ↑6 | For a fuller exploration into Mandan mythology and religion and the expedition members’ understandings of them, see Thomas P. Slaughter, Exploring Lewis and Clark: Reflections of Men and Wilderness (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2003), ch. 1. |

| ↑7 | The journalists’ role as ethnographers in the context of their stay at the Mandan villages is explored in James P. Ronda, Lewis and Clark among the Indians, Bison Book ed. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1984), 129–132. For ceremonies, see Wood and Irwin, 356–359. For more on the Medicine Stone, see Clay S. Jenkinson, A Vast and Open Plain: The Writings of the Lewis and Clark Expedition in North Dakota, 1804–1806 (Bismarck, North Dakota: State Historical Society of North Dakota, 2003), 222–23. |

| ↑8 | For a comparison of Evans’ and Clark’s maps, see on this site, Clark’s Fort Mandan Maps. |

| ↑9 | Wood and Irwin, 350; Aaron Cobia, “Prince Madoc and the Welsh Indians: Was there a Mandan Connection?,” We Proceeded On, August 2011, Vol.37 No. 3, Page 16. Available at https://lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol37no3.pdf#page=18. |

| ↑10 | Moulton, Journals, 3:201n5 and 202, fig. 4. For a full synonymy, see Douglas R. Parks, Handbook of North American Indians: Plains Vol. 13, 362–64. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.