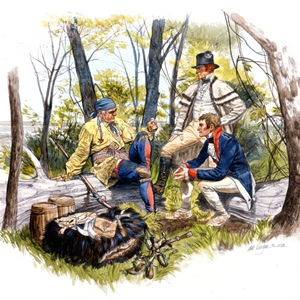

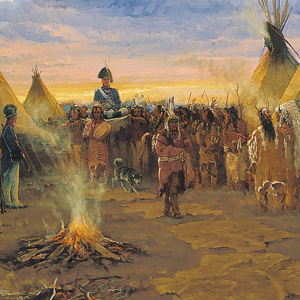

The Seven Bands

Unfinished Diplomacy

30″ x 52″ oil on canvas

© 2009 by Charles Fritz, http://charlesfritz.com. Used by permission.

Presently known as the Lakota people—often spelled Lahkota or more phonetically, lakhóta—Lewis and Clark most often called them Tetons. Teton is an English borrowing from Thíthuwa which despite numerous interpretations from historians and writers, has no definite meaning. Teton peoples are often referred to by the name of their band. There were three main groups, the Oglala, Brule, and Saone, and the latter group was divided into the Minneconjou, Hunkpapa, Sans Arc, Two Kettles, and Blackfoot—not to be confused with the Algonquian-speaking Blackfoot. Collectively, they are often called the seven bands of the Lakota Nation. At the time of the expedition, the bands typically lived separately, hunted freely within each other’s territory, and came together for community events. There was no evidence, however, of a centralized Lakota government.[1]Raymond J. DeMallie, Handbook of North American Indians: Plains Vol. 13 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 2001), 794.

An informative name for the Teton is the Plains Sign Language gesture for the Sioux in general, a motion denoting cut throats and head decapitations.[2]Douglas R. Parks, Handbook of North American Indians: Plains Vol. 13, 749–751, 755. Also clear is the captains’ belief that the Teton Sioux threatened American trade in the upper Missouri:

These are the vilest miscreants of the savage race, and must ever remain the pirates of the Missouri, until such measures are pursued, by our government, as will make them feel a dependence on its will for their supply of merchandise. Unless these people are reduced to order, by coercive measures, I am ready to pronounce that the citizens of the United States can never enjoy but partially the advantages which the Missouri presents.[3]Moulton, Journals, 3:418

The Tetons were relatively new to the Missouri, and also relatively new to world of trade. Siouan-speaking peoples—possibly part of the Mound Builder culture during their prehistory—were recorded by early French explorers and missionaries as generally moving westward from Lake Michigan to lands between the Mississippi and Missouri rivers. Only after the smallpox epidemics of the late 18th century decimated the Arikaras, Mandans, and Hidatsas, did the Teton Sioux move into lands west of the Missouri. Immediately following the expedition, the Arikaras—not the Teton Sioux—became the gatekeepers of the American trade in the upper Missouri. The Tetons’ battles with America would come in the second half of the 19th century.

Encounters

That the expedition experienced Lakota Sioux Difficulties in late September 1804 is one of the more commonly related experiences of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Two Sioux attacks, perhaps the Teton, occurred during the winter at Fort Mandan. Wanting to protect their hosts, the Mandans and Hidatsas, the captains ordered a military response. That show of force did not result in actual skirmishes. A third encounter was an attack on a hunting party. Joseph Whitehouse, on 14 February 1805, records that the hunters’ horses and weapons were taken by marauding Sioux. After a gift of cornbread, one of the horses was given back, and the party was able to safely return to the Knife River Villages.

On the 1806 return home, the captains went out of their way to avoid the Teton Sioux. After leaving the Arikara, the captains took evasive actions at the first sign of any nearby Indians. After a couple of false alarms, they finally met some Teton Sioux on 30 August 1806 who beckoned the captains to meet with them. The captains refused, essentially told the men off, and received a rude gesture in return. If anyone else offered insults or gestures during the encounter, they were omitted from the written record.

Treaties and Wars

The Treaty of 1851, for the first time, established boundaries for the Teton Sioux and other participating bands. Annuities for over half a century were promised in return for the right to build roads and military posts on Sioux lands. Thereafter, conflicts due to cultural and political misunderstandings between Oregon Trail emigrants, overzealous U.S. Army commanders, and treaty signers led to raids, massacres, and wars.[4]DeMallie, 795.

To protect Powder River lands, Oglala Red Cloud led a series of successful battles against the U.S. Army. Red Cloud’s War precipitated the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie that established the Great Sioux Reservation—including the Black Hills—for the Oglala, Miniconjou, Brulé, Yanktonai, and Arapaho signers. Hunkpapa Sitting Bull refused to sign and would become a symbol of native resistance and independence.[5]“Red Cloud’s War,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Red_Cloud%27s_War accessed on 30 January 2021.

In 1874, Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer led the Black Hills Expedition to locate a site for a military post. The fact that Custer also found gold leaked to the public, and the Army was unable to stop prospectors from trespassing on Sioux lands. In May 1875, Sioux delegations including Brulé Spotted Tail, Red Cloud, and Minneconjou Lone Horn tried to persuade U.S. President Grant to honor the former treaties and keep the miners out. That fall, one meeting between government and Sioux representatives was held and the diplomatic solution was essentially abandoned.[6]DeMallie, 797.

Of the Lakota people’s struggles and conflicts between 1850 and 1890, much has been written. Many Lakota leaders became icons of independence, resistance, military leadership, bravery, and spirituality. Sitting Bull, whose Sun Dance vision prophesized of the defeat of Custer, was killed by Army soldiers with questionable motives as he was being arrested at Standing Rock at the end of 1890. Just two weeks later, on 29 December, nearly three hundred Lakota people would be killed at the Battle of Wounded Knee, also known as the Wounded Knee Massacre. After fighting with Crazy Horse at the Battle of the Little Bighorn and surviving the Wounded Knee Massacre, Oglala medicine man Black Elk worked with ethnologists to document his life and Oglala spiritual practices, notably in two books, The Sacred Pipe and Black Elk Speaks. His books have inspired both native and non-native peoples for generations.[7]DeMallie, 797; “Black Elk,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Elk and “Sitting Bull,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sitting_Bull both accessed 30 January 2021.

Today, one half of enrolled Teton Sioux reside among several reservations each with a separate government.[8]“Lakota People,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lakota_people, accessed 21 January 2021. These include:

- Rosebud Indian Reservation: “home of the federally recognized Sicangu Oyate (the Upper Brulé Sioux Nation) also known as Sicangu Lakota, and the Rosebud Sioux Tribe”[9]“Rosebud Indian Reservation,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rosebud_Indian_Reservation, accessed 30 January 2021.

- Lower Brulé Indian Reservation[10]“Lower Brulé Indian Reservation,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lower_Brule_Indian_Reservation, accessed 30 January 2021.

- Pine Ridge Indian Reservation: home of the federally recognized Oglala Sioux Tribe[11]“Oglala,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oglala, accessed 30 January 2021.

- Standing Rock: Home to several Sioux subgroups including the Hunkpapa[12]“Standing Rock Indian Reservation,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Standing_Rock_Indian_Reservation, accessed 30 January 2021.

- Cheyenne River Indian Reservation: “home of the federally recognized Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe or Cheyenne River Lakota Nation (Oyate).” It also includes Miniconjou, Sans Arc, Blackfoot, and Two Kettles.[13]“Cheyenne River Indian Reservation,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cheyenne_River_Indian_Reservation, accessed 30 January 2021.

- Fort Berthold

- Various others in the United States and Canada

For Further Reading

- Pekka Hämäläinen, Lakota America: A New History of Indigenous Power (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019)

- Stephen E. Ambrose, Crazy Horse and Custer (New York: Anchor Books, 1996)

- Dee Brown, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1971)

- John S. Gray, Centennial Campaign: The Sioux War of 1876 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1988).

- Donald Jackson, Custer’s Gold: The United States Cavalry Expedition of 1874 (New Haven, 1966).

- John G. Neihardt, Black Elk Speaks (Norman: Bison Books, 1961).

Selected Pages and Encounters

September 24, 1804

Smoking with Buffalo Medicine

Pierre, SD As the boats continue towards the Lakota Sioux villages, Colter’s horse is stolen. A promise is made to return the horse and to meet with the captains tomorrow.

Flag Presentations

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Lewis and Clark usually distributed flags at councils with the chiefs and headmen of the tribes they encountered—one flag for each tribe or independent band.

September 30, 1804

Sailing away

Little Bend Rec. Area, SD The expedition meets a band of Sioux who invite the captains to stop and eat with them. The captains decline and give them some tobacco. An accident induces a Sioux chief to leave the barge.

September 25, 1804

Good humor left behind

Pierre, SD At Good Humor Island, a council with the Lakota Sioux brings diplomatic speeches, a military parade, and gifts. During a tour of the barge, relationships sour. When they try to disembark, Clark draws his sword.

September 22, 1804

Passing Fort aux Cedres

Below De Grey Rec. Area, SD The expedition passes the abandoned Fort aux Cedres, a fur trading post built by Régis Loisel. Ordway describes the buildings and nearby Sioux camps. The hunters complain that the soils of the plains are wearing out their moccasins.

February 28, 1805

Arikara and Sioux news

Fort Mandan, ND Traders arrive with news of the Arikaras and Sioux and two plant specimens. About six miles from the fort, several men cut down cottonwood trees to make dugout canoes.

August 26, 1806

Passing the Bad River

Fort Thompson, SD While passing the Bad River, Clark recalls how the Lakota Sioux attempted to stop them in 1804. They make about sixty miles reaching an area where they now expect to find those Indians.

August 24, 1806

Lookout Bend

Lookout Bend, SD Despite high waves, the expedition paddles about forty-three miles. Clark explores a bluff containing bentonite clay and blames the Sioux for the area’s lack of game.

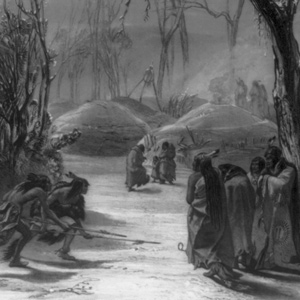

Lewis and Clark first met the Teton Sioux on 25 September 1804. One of Jefferson’s primary political objectives for the expedition was to create a peace treaty and trade agreement them, the most potent military and economic force on the lower Missouri.

September 23, 1804

Signaling the Teton Sioux

Below Pierre, SD The boats make twenty more miles. Three Lakota Sioux boys swim out to say they set signal fires to tell their villages that the expedition is coming. The captains ask them to invite their chiefs to council.

September 12, 1806

Old acquaintances

St. Joseph, MO The captains meet four old acquaintances, an old military companion and three men from the 1804 upriver trip.Joseph Gravelines and Pierre Dorion are acting under orders from President Thomas Jefferson, which the captains review and modify.

On the evening of 25 September 1804 after a negative encounter with the Lakota Sioux, the Corps camped on a nearby island Clark called “bad humered Island.” The next morning, the Indians had a change of heart.

November 30, 1804

A military reprisal

Fort Mandan, ND Responding to news of a deadly Sioux and Arikara attack on Mandan and Axaxawi Hidatsa hunters, Clark leads a military force to Mitutanka to gather warriors and pursue the Sioux. His intentions are appreciated, but he is convinced to abandon the plan.

September 27, 1804

A lost anchor

Pierre, SD An anchor line is accidentally severed, and the men must act quickly to save the boat. The Lakota Sioux think they are under attack. The captains suspect the Sioux are forming their own attack.

October 22, 1804

Double Ditch village

North of Harmon, ND During the night, Clark has a bout of rheumatism. During the day, they meet a group of Lakota Sioux on a raid. The expedition camps three miles above the abandoned Mandan Double Ditch villages.

September 26, 1804

Teton Sioux ceremony

Pierre, SD Clark and Lewis are ceremoniously carried into a Lakota Sioux village where they are feted with food and music. Clark sees several recently-captured Omaha prisoners and asks for their return.

The visit to this prairie hill was among the more bizarre sidelights of the whole expedition, but evidently it was not entirely unexpected. Seventy-six years earlier, explorer Pierre La Véndrye called the place the “Dwelling of the Spirits.”

August 30, 1806

Armed Lakotas

Academy, SD When several armed Lakotas appear on the opposite shore, Clark recognizes them and through interpreters tells them to stay away or be killed. After the hunters catch up, they move on and camp on a large sandbar in a defensive position.

September 6, 1806

A taste of whiskey

Little Sioux River, IA The flotilla meets a large boat owned by Auguste Chouteau of St. Louis. Some men trade beaver skins for linen shirts and woven hats. They also enjoy their first whiskey since the 1805 Fourth of July.

February 16, 1805

Scorched earth

Fort Mandan, ND Lewis and his men continue their pursuit of a Sioux war party and come to an old Mandan village where the hunter’s cache of meat that has been pillaged and two lodges set afire.

September 3, 1806

News from home

Sioux City, IA Trader James Aird is heading up the river to trade with the Sioux bringing news from home. The captains learn that Jefferson is still president, James Wilkinson is now Louisiana governor, and Alexander Hamilton died in a duel with Aaron Burr.

August 15, 1806

Broken promises of peace

Knife River Villages, ND The captains hear of several broken promises of peace among tribes they had worked with on the outward journey. Colter asks to leave the expedition so that he can go back west with two fur trappers.

August 25, 1806

Empty Lakota encampment

Above Pierre, SD The boats stop at the Cheyenne River so that the captains can take celestial observations, and the men can hunt. Passing an empty Lakota encampment, they recall the “Troubleson Tetons” on their way up the river in 1804.

Ignorant of plains politics, Lewis and Clark barely averted disaster in their encounter with Black Buffalo’s people—an article by James P. Ronda from a keynote address to the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation, Pierre, South Dakota, August 2002.

September 28, 1804

Leaving the Teton Sioux

Above Gavins Point Dam, SD When a lost anchor cannot be found the expedition tries to leave, but Lakota Sioux warriors grab the boat’s line. Weapons are readied, but eventually the chief concedes for a carrot of tobacco. Tensions remain high throughout the day.

September 29, 1804

New Teton Sioux territory

Spring Creek, SD The boats continue up the Missouri River through territory taken from the Arikaras by the Sioux. Indians ask for tobacco and at night, all but the guard sleep on the boats.

Notes

| ↑1 | Raymond J. DeMallie, Handbook of North American Indians: Plains Vol. 13 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 2001), 794. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Douglas R. Parks, Handbook of North American Indians: Plains Vol. 13, 749–751, 755. |

| ↑3 | Moulton, Journals, 3:418 |

| ↑4 | DeMallie, 795. |

| ↑5 | “Red Cloud’s War,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Red_Cloud%27s_War accessed on 30 January 2021. |

| ↑6 | DeMallie, 797. |

| ↑7 | DeMallie, 797; “Black Elk,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Elk and “Sitting Bull,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sitting_Bull both accessed 30 January 2021. |

| ↑8 | “Lakota People,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lakota_people, accessed 21 January 2021. |

| ↑9 | “Rosebud Indian Reservation,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rosebud_Indian_Reservation, accessed 30 January 2021. |

| ↑10 | “Lower Brulé Indian Reservation,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lower_Brule_Indian_Reservation, accessed 30 January 2021. |

| ↑11 | “Oglala,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oglala, accessed 30 January 2021. |

| ↑12 | “Standing Rock Indian Reservation,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Standing_Rock_Indian_Reservation, accessed 30 January 2021. |

| ↑13 | “Cheyenne River Indian Reservation,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cheyenne_River_Indian_Reservation, accessed 30 January 2021. |