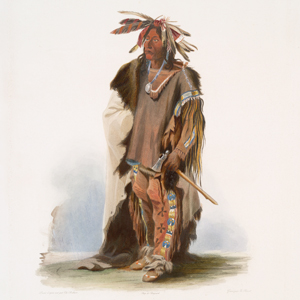

Wahktágeli, Yankton Sioux Chief

Karl Bodmer (1809–1893) circa 1833

Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library.[1]“Wahk-Tä-Ge-Li, Dacota-Krieger. Wahk-Tä-Ge-Li, Guerrier Dacota. Wahk-Tä-Ge-Li, a Sioux Warrior.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed February 22, 2019. … Continue reading

The Yankton along with the Yanktonai make up the Western Dakota division of the Dakota People. Although the Yankton and Yanktonai sometimes considered themselves to be one people, their separate locations resulted in a unique history for each. First mentioned on Father Louis Hennepin’s map of 1683, the Yanktons were located between Mille Lacs Lake and Lake of the Woods in northern Minnesota. La Sueur moves them south and west to the Pipestone Quarry close to where Lewis and Clark met them in 1804.[2]Raymond J. DeMallie, Handbook of North American Indians: Plains Vol. 13 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 2001), 777; Frederick Webb Hodge, Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico, … Continue reading

Encounters

As they appear in the daily journal entries, the Yankton Sioux were the good guys. Certainly the greetings, councils, and celebrations went well during the final days of August 1804—even more so when contrasted against the Lakota Sioux difficulties in late September of the year. The captain’s report on the Eastern Indians, written while wintering at Fort Mandan, held a much less favorable opinion towards the people. In it, the captains complained that the Yankton:

furnished [the Lakota Sioux] with the means, not only of distressing and plundering the traders of the Missouri, but also, of plundering and massacreing the defenceless savages of the Missouri, from the mouth of the river Platte to the Minetares [Hidatsas], and west to the Rocky mountains.

As for the other division of the Western Dakota, the captain thought the conduct of the Yanktonai somewhat better:

These are the best disposed Sioux who rove on the banks of the Missouri, and these even will not suffer any trader to ascend the river, if they can possibly avoid it: they have, heretofore, invariably arrested the progress of all those they have met with, and generally compelled them to trade at the prices, nearly, which they themselves think proper to fix on their merchandise . . . .[3]Moulton, Journals, 3:414.

The expedition never met the Yanktonai, but on 5 April 1804, they gave written queries, instructions, a speech, and Indian commissions (paroles) to St. Louis trader Lewis Crawford. He was tasked to deliver those items to the Iowas and Sioux—most likely the Yanktonai, collect vocabularies, and send delegates for Washington City via St. Louis. According to various correspondence, while the expedition struggled up the Missouri in 1804 and wintered until April 1805, Crawford fulfilled the captains’ request and sent delegates down the Mississippi to St. Louis.[4]Lewis to Amos Stoddard 16 May 1804 in Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents: 1783-1854, 2nd ed., ed. Donald Jackson (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 190; Amos … Continue reading

History

The Yanktons were present at the 1851 Treaty Council (See “Treaties and Wars” in Teton Sioux). However, the pivotal treaty for the nation came in 1858 in which Charles Picotte, signing as the people’s legal representative—a representation disputed by many members, ceded all lands in exchange for the Yankton Reservation in South Dakota and formalized their role as caretakers of the Pipestone Quarry. The latter would not be clarified, at least legally, until 1929. In 1859, the people would start campaigning for the annuities and school that were also promised in that treaty.

In 1878, some Yankton Sioux began moving to farms in anticipation of the coming severing of the reservations into private allotments. By 1980, 1,481 Yanktons took allotments and four years later, the remaining allotments were sold to whites—about half of the reservation.[5]DeMallie, 777–780, 791.

Today, many Yankton maintain tribal governments through several reservations in the United States and Canada. Of note, is the Yankton Sioux Tribe of South Dakota headquartered in the Yankton Indian Reservation.[6]“Yankton Sioux Tribe,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yankton_Sioux_Tribe, accessed 30 January 2021.

Selected Pages and Encounters

Flag Presentations

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Lewis and Clark usually distributed flags at councils with the chiefs and headmen of the tribes they encountered—one flag for each tribe or independent band.

Spirit Mound

An elevation of devilish spirits

by Joseph A. Mussulman

The visit to this prairie hill was among the more bizarre sidelights of the whole expedition, but evidently it was not entirely unexpected. Seventy-six years earlier, explorer Pierre La Véndrye called the place the “Dwelling of the Spirits.”

August 27, 1804

Yankton Sioux visitors

Reaching present Yankton, South Dakota, they set a fire to signal the Sioux to a council. A Yankton man and two boys arrive. Drouillard fails to find Pvt. Shannon who hasn’t returned from a hunting trip.

August 29, 1804

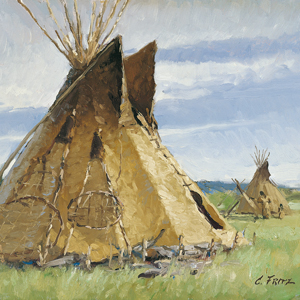

Seventy Yanktons arrive

In present South Dakota, Sgt. Pryor and Old Dorion bring in a large delegation of Yankton Sioux. Clark writes about their “Conic” lodges and is presented a fat dog which he finds “good & well flavored”.

August 30, 1804

Yankton council and dance

At a council with the Yankton Sioux, Lewis delivers a speech, gifts given, and a peace pipe passed. Clark learns about the Akicita Society, and Sgt. Ordway finds their musical instruments interesting.

August 31, 1804

Yankton speeches

The council with the Yankton Sioux continues with many of them giving speeches while Clark and Sgt. Ordway take notes. Trader Pierre Dorion is assigned a mission to make peace with the region’s Nations.

February 28, 1805

Arikara and Sioux news

Traders arrive at the Knife River Villages with news and two plant specimens for Lewis. About six miles from Fort Mandan, several enlisted men cut down cottonwood trees to make dugout canoes.

August 11, 1806

Cruzatte shoots Lewis

Lewis is shot through the buttock. An Indian attack is suspected, but likely Pvt. Cruzatte mistook him for an elk. Clark meets fur traders who share news of the barge, the fur trade, and Indian wars.

September 1, 1806

Calumet Bluff anniversary

Clark expresses relief when some Indians turn out to be Yankton Sioux who give news of the fur trade. In the evening, they camp opposite their Calumet Bluff council site of 1 September 1804.

September 2, 1806

Stopping to hunt

Delayed by wind, Clark pulls in below the James River in present South Dakota, and bison hunting consumes most of the day. Their Indian delegates see their first turkeys and find them impressive.

September 3, 1806

News from home

Moving down the Missouri, they meet a group of traders who tell them that Jefferson is again president and that Alexander Hamilton died in a duel with Aaron Burr. They camp above present Sioux City, Iowa.

September 6, 1806

A taste of whiskey

Moving down the Missouri along the present Nebraska-Iowa border, the expedition meets a large boat owned by Auguste Chouteau of St. Louis. Some men trade beaver skins for linen shirts and woven hats.

Notes

| ↑1 | “Wahk-Tä-Ge-Li, Dacota-Krieger. Wahk-Tä-Ge-Li, Guerrier Dacota. Wahk-Tä-Ge-Li, a Sioux Warrior.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed February 22, 2019. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-c433-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Raymond J. DeMallie, Handbook of North American Indians: Plains Vol. 13 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 2001), 777; Frederick Webb Hodge, Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico, Vol. 2 (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology, Government Printing Office, 1910), 988–89. |

| ↑3 | Moulton, Journals, 3:414. |

| ↑4 | Lewis to Amos Stoddard 16 May 1804 in Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents: 1783-1854, 2nd ed., ed. Donald Jackson (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 190; Amos Stoddard to Henry Dearborn, 3 June 1804 in Jackson, 196; Amos Stoddard to Jefferson, 29 October 1804 in Jackson, 212–213; Amos Stoddard to Jefferson, 24 March 1805 in Jackson, 221; and Pierre Chouteau to William Henry Harrison, 22 May 1805 in Jackson, 243. |

| ↑5 | DeMallie, 777–780, 791. |

| ↑6 | “Yankton Sioux Tribe,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yankton_Sioux_Tribe, accessed 30 January 2021. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.