Coyote was coming. He came to Gōt’a’t. There he met a heavy surf. He was afraid that he might be drifted away and went up to the spruce trees. He stayed there a long time. Then be took some sand and threw it upon that surf: ”This shall be a prairie and no surf. The future generations shall walk on this prairie. Thus Clatsop became a prairie. The surf became a prairie.

At Niā’xaqcē a creek originated. He went and built a house at Niā’xaqcē. He went out and stayed at the mouth of Niā’xaqcē.

The Clatsops’ Plain

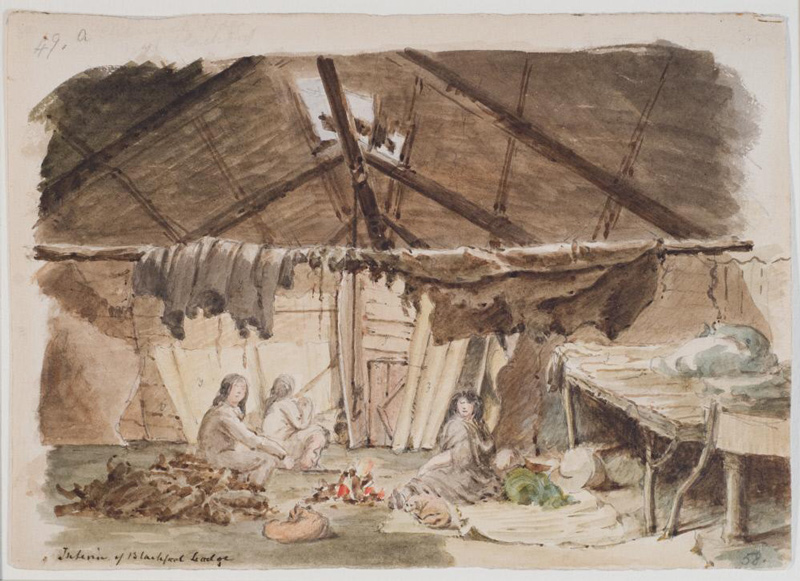

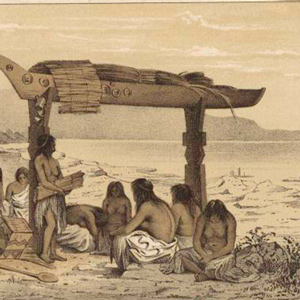

A Chinook Lodge (1846–47)

Paul Kane (1810–1871)

Watercolor and pencil on paper, 5 1/8 x 7 1/4 inches (13 x 18.4 cm). Courtesy Stark Museum of Art, bequest of H.J. Lutcher Stark, 1965.

The lodge in this figure was likely a Skilloot lodge near the mouth of the Cowlitz River. It is unlikely that the artist traveled any further down the river. He described Chinookan Peoples:

During the season the Chinooks are engaged in gathering camas and fishing, they live in lodges constructed by means of a few poles covered with mats made of rushes, which can be easily moved from place to place; but in the villages they build permanent huts of split cedar boards. . . . In the centre of this lodge the fire is made, and the smoke escapes through a hole left in the roof for that purpose.

The fire is obtained by means of a small flat piece of dry cedar, in which a small hollow is cut, with a channel for the ignited charcoal to run over; this piece the Indian sits on to hold it steady, while he rapidly twirls a round stick of the same wood between the palms of his hands, with the point pressed into the hollow of the flat piece. In a very short time sparks begin to fall through the channel upon finely frayed cedar bark placed underneath, which they soon ignite. There is a great deal of knack in doing this, but those who are used to it will light a fire in a very short time.[2]Paul Kane, Wanderings of an Artist among the Indians of North America . . . . (London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans, and Roberts, 1859), 187–89. See also Chinookan Houses and Making Fire.

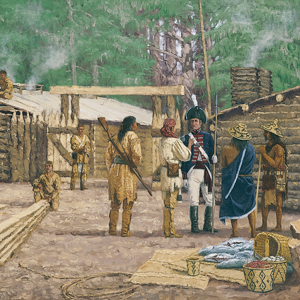

Clark visited Clatsop lodges like these at present-day Seaside, Oregon. When building Fort Clatsop, men were dispatched to collect cedar boards from other empty villages. Those planks were used as roofing. For more on the give and take between the expedition and Clatsops, see Clatsop Give and Take.

For the Chinookan peoples, Coyote joins other beings from the Myth Age: Blue Jay, Salmon, and Grizzly Woman among others. The creek where he built his legendary house—today’s Neacoxie Creek—flows north to south bisecting nearly the length of the Clatsop Plain. A village at the estuary created by the ocean, Neacoxie Creek and the larger Necanicum River is Ne-ah-coxie Village. Nearby were three other Clatsop villages, and for a short time, a salt works built by soldiers from the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

The Neacoxie for a time parallels the Skipanon River. The latter conveniently flows north to the Columbia where there were at least three more Clatsop Villages. One was located along Tansy Creek the 1851 meeting site of what are known as the Tansy Point Treaties—a significant event in the history of Chinookan Peoples.[3]David V. Ellis, Chinookan Peoples of the Lower Columbia, ed. Robert T. Boyd, et al. (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2013), 44; Henry B. Zenk, Yvonne P. Hajda, and Robert T. Boyd, … Continue reading

Chinookan Slaves

During the 1805–06 winter at Fort Clatsop, the Clatsops were the expedition’s nearest neighbors, and interactions were numerous. On the last day of February 1806, Clatsop Cuscalar and his wife came to the fort to sell eulachon, sturgeon, a beaver robe, and some roots. They also offered to sell a slave—a “good looking boy of about 10 years of age” wrote Lewis—for “beeds & a gun” wrote Clark. Slaves were pervasive throughout Clatsop, Chinookan, and Coastal nations and were acquired mostly through trade. Slaves were not allowed to flatten their heads (see Chinookan Head Flattening) and a person’s wealth could be gauged by the number of ’round heads’ paddling the canoe.[4]Hadja, Chinookan Peoples . . ., 157–158; Michael Silverstein, Handbook of North American Indians: Northwest Coast Vol. 7, ed. Wayne Suttles (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian … Continue reading

The captains reported that the Clatsop adopted their slaves and “treat[ed] them very much as their own children.” The historical record is very different. Slave adoption was rare and slaves who became ill were often neglected.[5]Hadja, Chinookan Peoples . . ., 158. During his 1824–25 inspection tour of Canada and the Hudson’s Bay Columbia Department, Governor-in-Chief George Simpson wrote:

Slaves form the principal article of traffick on the whole of this Coast and constitute the greater part of their Riches; they are made to Fish, hunt, draw Wood & Water in short all the drudgery falls on them; they feed in common with the Family of their proprietors and intermarry with their own class, but lead a life of misery, indeed I conceive a Columbia Slave to be the most unfortunate Wretch in existence; the proprietors exercise the most absolute authority over them even to Life and Death and on the most trifling fault wound and maim them shockingly.[6]George Simpson, Fur Trade and Empire: George Simpson’s Journal, ed. Frederic Merk (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1968), 101.

European Diseases

On 7 February 1806, Lewis recorded what they had learned about smallpox among the Chinookan peoples:

The small pox has distroyed a great number of the natives in this quarter. it prevailed about 4 years since among the Clatsops and distroy several hundred of them, four of their chiefs fell victyms to it’s ravages. those Clatsops are deposited in their canoes on the bay a few miles below us. I think the late ravages of the small pox may well account for the number of remains of vilages which we find deserted on the river and Sea coast in this quarter.—

The 1801 epidemic had come from the Northern Rockies. The year and direction of an earlier epidemic, also reported in the Lewis and Clark journals, is harder to define. Ethno-historian Robert Boyd finds that recently discovered oral tradition supports the theory that the first epidemic, in the early 1780’s, came from contact with ships. Another theory has that epidemic coming from Plains Indians. Boyd states that it is also possible the epidemic struck from both directions.[7]Robert T. Boyd, Chinookan Peoples . . ., 236.

In addition to recurring waves of smallpox, alcoholism and malaria also plagued Chinookan peoples. The “fever and ague” or “intermittent fever” broke out in 1830 among both the Chinook and the Fort Vancouver employees. The malaria may have come from the ships Owyhee and Convoy or from traders who had previous contact with malarial tribes along the Mississippi.[8]Robert T. Boyd, Handbook . . ., 138.

Based on population counts, including those of Lewis and Clark in their Estimate of the Western Indians, populations declined as much as 92% from European diseases. Clatsop and Chinookan survivors were left with “a heritage of fear” which traders sometimes used to their advantage.[9]Robert T. Boyd, Chinookan Peoples . . ., 237.

Return to Neacoxie

At the Necanicum River estuary complex, Clark recorded four houses comprised of both Clatsops and Tillamooks, an affiliation that continues today. In 2001, they formed the Clatsop-Nehalem Confederated Tribes. Like the Chinooks, they have not been able to obtain federal recognition. In May 2020, the confederation obtained the 18.6 acre Neawanna Point Habitat Preserve on the Necanicum Estuary. Now renamed Ne-ah-coxie Village, this saltmarsh and forest is once again owned and shared by Clatsop and Nehalem Tillamook.[10]Robert H. Ruby, John A. Brown, and Cary C. Collins, A Guide to the Indian Tribes of the Pacific Northwest (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010), 42; “Clatsop-Nehalem tribes … Continue reading

Selected Pages and Encounters

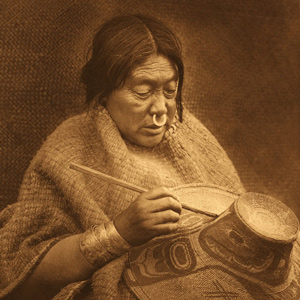

Clatsop Cone Hats

by Joseph A. Mussulman

They could come up with nothing in the way of hats that was as practical as the style perfected by the Clatsops and Chinooks.

Flag Presentations

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Lewis and Clark usually distributed flags at councils with the chiefs and headmen of the tribes they encountered—one flag for each tribe or independent band.

November 21, 1805

Clatsop and Chehalis visitors

At Station Camp near the mouth of the Columbia, some Clatsops and Lower Chehalis visit, and the wife of Chinook chief Delashelwilt brings six young females to camp. Clark describes Chinookan woven hats.

November 23, 1805

Marking the territory

At Station Camp on Baker Bay, Lewis brands a tree and then, Clark and several of the party make marks of their own. Clatsop visitors come to trade for blue beads, and in the evening, the weather clears.

December 3, 1805

Food for the sick

At their Tongue Point bivouac, spirits lift when the morning proves fair and fresh elk meat arrives. Clark and several enlisted men find healing in the wapato and marrow.

December 9, 1805

The Necanicum Clatsop Village

Looking for a place to make salt, Clark meets three Necanicum Clatsops who take his group to their village at present Seaside, Oregon. At the Fort Clatsop site, construction begins on a “small fort”.

December 10, 1805

Beachcombing

Clark combs the beach while Necanicum villagers look for fish stranded by the retreating tide. He returns to the Fort Clatsop construction site, where workers are falling trees and building a foundation.

December 12, 1805

Coboway's peace medal

Two canoes of Clatsops come to the construction site to trade wapato and a sea otter skin. The captains give a medal to Chief Coboway, and Clark describes the Clatsop’s desire for blue beads.

December 13, 1805

Cat skins

At the Fort Clatsop construction site, the captains trade for bobcat and lynx furs. Two hunters return having left several butchered elk in the woods, and workers attempt to split grand fir into boards.

December 18, 1805

The gray jay, new to science

At Fort Clatsop, the morning brings rain, snow, and hail. Several men bring in planks taken from an old Chinookan fishing camp across Youngs Bay, and Lewis describes the gray jay, new to science.

Clatsop Give and Take

Dubious interactions

by Joseph A. Mussulman

In mid-March the men stole a Clatsop canoe as recompense for Indians’ theft of 6 elk carcasses the men had shot, even though the tribe’s chief had already made restitution for the elk by giving the captains three free dogs.

December 19, 1805

'Borrowing' Clatsop boards

Several Clatsops visit the fort construction site, and everyone except Sgt. Ordway is in good health. Sgt. Pryor heads a detachment across Youngs Bay to retrieve boards from an abandoned Clatsop house.

December 21, 1805

Harvesting kinnikinnick

At the Fort Clatsop site, the enlisted men daub and chink their cabins but have difficulty splitting logs into puncheons. Two men are harvesting kinnikinnick to mix with the little tobacco they have left.

December 23, 1805

Clatstop traders

At Fort Clatsop, work on the cabins continues, and the captains move into their unfinished quarters. Clatsop traders sell food, mats, bags, and a panther hide for fishhooks, an old file, and spoiled salmon.

December 24, 1805

New writing slabs

At Fort Clatsop, all the cabins are covered and several enlisted men move into their quarters. The captains refuse offers made by a visiting Clatsop chief, and Pvt. J. Field gives each captain a writing slab.

December 27, 1805

Chimneys

At Fort Clatsop, the enlisted men are hunting, setting up a salt works, building chimneys, or making pickets and gates. Coboway brings roots and receives a sheepskin headband and earrings in return.

Chinookan Woven Hats

by Mary Malloy

Today five hats at the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology (PMAE) at Harvard University have a provenance that potentially associates them with the Lewis and Clark expedition. These hats represent an extensive network of trade.

December 29, 1805

Wahkiakum traders

Clark gives visiting Wahkiakum traders a small peace medal and ties a red ribbon to a cone hat; Clatsop chief Coboway is given a razor. Clark also lists the day’s work details and sick men.

December 31, 1805

Latrine and sentry box

At Fort Clatsop, an Indian’s musket is repaired, and a red-headed Clatsop is among the many visitors today. Clark notes that their behavior has improved, and a new latrine and sentry box are added.

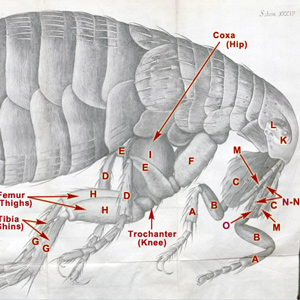

January 2, 1806

Infested with fleas

Fort Clatsop, Astoria, OR A few hunters and two men from the salt works are missing, and Clatsop traders leave. Aquatic birds, local furs, and problems with fleas are noted.

January 3, 1806

Fresh whale blubber

Fort Clatsop, Astoria, OR Visiting Clatsops sell roots, berries, fresh whale blubber, and dogs. Three hunters return empty-handed, and two men are sent to bring Willard and Weiser back from the salt maker’s camp.

January 4, 1806

Jefferson's Indian speech

Fort Clatsop, OR Gass and Shannon travel t to the salt makers’ camp, and Lewis describes Clatsop Indian views on material goods. In Washington City, President Jefferson meets with an Indian delegation organized in part by Lewis and Clark.

January 6, 1806

Sacagawea's plea

Fort Clatsop, Astoria, OR Sacagawea pleads to be permitted to see the beached whale, and her wish is “indulged.” Lewis describes the status of Chinookan women and laments the expedition’s paucity of trade goods.

January 7, 1806

Clark's Point of View

Fort Clatsop and Tillamook Head, OR Clark’s group travels several miles along the beach to reach the Salt Works. From there, they climb up the very “Pe Shack” (bad) headland they called “Clark’s Point of View.”

January 9, 1806

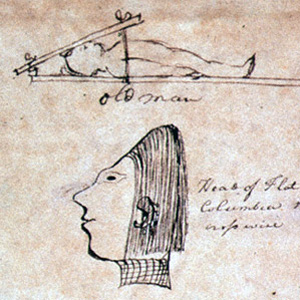

Canoe-style burials

Fort Clatsop and Necanicum Village, OR Clark’s party crosses Tillamook Head and returns to the salt works with whale oil and blubber. At Fort Clatsop, Lewis describes canoe burials and the language of the Chinookan Peoples.

January 11, 1806

Lost Chinookan canoe

Fort Clatsop, OR Careless paddlers fail to properly secure a canoe the previous night, and it floats away with the tide. Several men search for the lost Chinookan canoe without any luck. In Washington City, President Jefferson says the visiting Indian delegation will soon leave.

January 13, 1806

Running out of candles

Fort Clatsop, Astoria, OR Elk tallow is rendered to make new candles, Lewis finds that the area’s elk do not have enough fat to make a sufficient supply, and President Jefferson writes to Lewis’s mother with news of the expedition’s progress.

January 15, 1806

Lewis's new fur coat

Fort Clatsop, Astoria, OR Lewis’s new fur coat is made from seven bobcat—and perhaps mountain beaver—robes purchased from the Indians. He describes Chinookan hunting methods and weaponry.

January 17, 1806

Hats, mats, and baskets

Fort Clatsop, Astoria, OR Lewis describes the eating utensils used by the Chinookan Indians including woven baskets and hats. A Clatsop man refuses to trade his otter skin robe for anything other than blue beads.

January 18, 1806

Chinookan houses

Fort Clatsop, OR With little happening on this day, the captains describe the large Chinookan plankhouses they have seen.

January 19, 1806

Last of the blue beads

Fort Clatsop, OR The captains trade the last of the blue beads for a sea otter skin. They also buy a woven hat made in the shape of a cap recently popular in Britain and the United States.

January 24, 1806

Astonishing weaponry

Fort Clatsop, OR Several Indians are impressed with Drouillard’s rifle and shooting skills. Lewis demonstrates his air gun and describe how local Indians use seashore lupine.

January 28, 1806

Naming the Netul

The captains adopt the Clatsop word to name the Netul—present Lewis and Clark River. Two arrive at Fort Clatsop with a fresh supply of salt and say the salt makers are “much straitened for provision”.

January 30, 1806

Chinookan lifeways

Fort Clatsop, Astoria, OR Lewis says that nothing worthy of notice happens on this day. He describes Chinookan lifeways including, dress, hats, and double-edge knives.

February 3, 1806

Seven elk in peril

Hunters leave some elk near a Clatsop village, and Lewis worries they are in peril of being stolen. Four men arrive from the salt works with two bushels of salt and some whale blubber.

February 7, 1806

The ravages of smallpox

After a dinner of elk marrow bones and brisket, Lewis sarcastically says they are living in high style at Fort Clatsop. He describes the ravages of smallpox among the Clatsop and a local species of huckleberry.

February 18, 1806

Chinookan traders

Fort Clatsop, OR Chinookan traders arrive with woven hats and furs to sell. Whitehouse shows Clark his bobcat robe, and Ordway’s attempt to reach the salt works fails.

February 22, 1806

New rain hats

Fort Clatsop, OR Two Clatsop women deliver the men’s woven hats ordered previously by the captains. The eulachon run begins, and Lewis describes pronghorns and bighorn sheep.

February 24, 1806

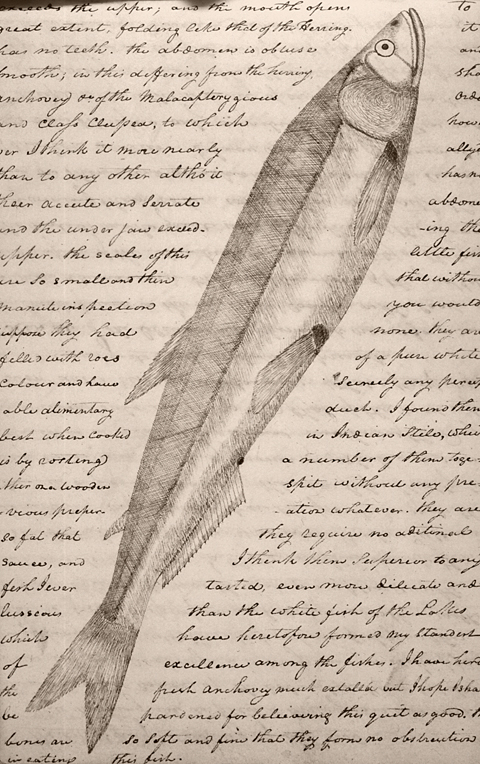

Cooking eulachon

Fort Clatsop, OR Several are sick and Sgt. Ordway writes that he has influenza. Lewis describes sea otters and seals.

February 25, 1806

Western gray squirrel

Fort Clatsop, OR With rain and violent winds, there is little movement today. Lewis describes the western gray squirrel, new to science.

March 6, 1806

Coboway and sons

Fort Clatsop, OR Coboway and two of his children bring cooked eulachon to Fort Clatsop, pleasing the captains. Detachments are sent to hunt and fish, several men are sick, and Lewis lists the aquatic birds of the area.

March 9, 1806

Swans

Fort Clatsop, OR Lewis describes various swans encountered on the journey. John Shields is tasked with making water-resistant bags, and Clatsop traders have beeswax for sale.

March 14, 1806

Canoe dealers

Fort Clatsop, OR Drouillard and a party of Clatsops arrive with a canoe for sale, but the captains fail to make a deal. Lewis describes steelhead and cutthroat trout.

March 15, 1806

Harvesting the hunt

Fort Clatsop, OR The captains continue to barter for canoes without success. Several men are busy hunting and gathering meat. Lewis describes the white-fronted goose, new to science.

March 16, 1806

A "scant dependence"

Fort Clatsop, OR Lewis writes an inventory of trade items: an artillerist’s uniform coat, five robes made from the large flag, some clothing, and little else. A run of coho salmon begins.

March 18, 1806

Stealing a canoe

Fort Clatsop, OR After stealing a canoe, soldiers hide it near the fort. The captains write a short description of the expedition with the names of each member, and they distribute copies among the Indians.

Chinookan Head Flattening

A most remarkable trait

by Joseph A. Mussulman, Kristopher K. Townsend

The most remarkable trait in the Clatsop Indian physiognomy, Lewis wrote on 19 March 1806, was the flatness and width of their foreheads, which they artificially created by compressing the heads of their infants, particularly girls, between two boards.

March 22, 1806

Giving away the fort

Fort Clatsop, OR In addition to giving away the fort, hunters are sent up the Columbia to hunt ahead of tomorrow’s planned departure.

March 25, 1806

Downstreamer Chinooks

As they paddle along the south shore of the Columbia, the expedition sees Downstreamer Chinooks trolling for sturgeon. After fifteen miles, they find a popular camping spot at the present Clatskanie River.

Fort Clatsop’s Legacy

by Joseph A. Mussulman

One of the first writers to devote special attention to the question of Fort Clatsop’s post-history was Olin D. Wheeler, who visited the site with Coboway’s grandson, Silas B. Smith, in 1900, and wrote briefly of it.

Notes

| ↑1 | Franz Boas, Chinook Texts (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1894), 101. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Paul Kane, Wanderings of an Artist among the Indians of North America . . . . (London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans, and Roberts, 1859), 187–89. See also Chinookan Houses and Making Fire. |

| ↑3 | David V. Ellis, Chinookan Peoples of the Lower Columbia, ed. Robert T. Boyd, et al. (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2013), 44; Henry B. Zenk, Yvonne P. Hajda, and Robert T. Boyd, “Chinookan Villages of the Lower Columbia,” Oregon Historical Quarterly, 2016, Vol. 117, No. 1, 8–9. For more on the Tansy Point Treaties, see Chinooks. |

| ↑4 | Hadja, Chinookan Peoples . . ., 157–158; Michael Silverstein, Handbook of North American Indians: Northwest Coast Vol. 7, ed. Wayne Suttles (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1990), 542–43. |

| ↑5 | Hadja, Chinookan Peoples . . ., 158. |

| ↑6 | George Simpson, Fur Trade and Empire: George Simpson’s Journal, ed. Frederic Merk (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1968), 101. |

| ↑7 | Robert T. Boyd, Chinookan Peoples . . ., 236. |

| ↑8 | Robert T. Boyd, Handbook . . ., 138. |

| ↑9 | Robert T. Boyd, Chinookan Peoples . . ., 237. |

| ↑10 | Robert H. Ruby, John A. Brown, and Cary C. Collins, A Guide to the Indian Tribes of the Pacific Northwest (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010), 42; “Clatsop-Nehalem tribes ‘dreaming again’ with return of ancestral land,” https://www.opb.org/article/2020/12/15/oregon-native-tribes-clatsop-seaside-land/, accessed 24 Feb 2021. |