Behold, all ye that kindle a fire, that compose yourselves about with sparks: walk in the light of your fire, and in the sparks that ye have kindled.

Matches and Magic

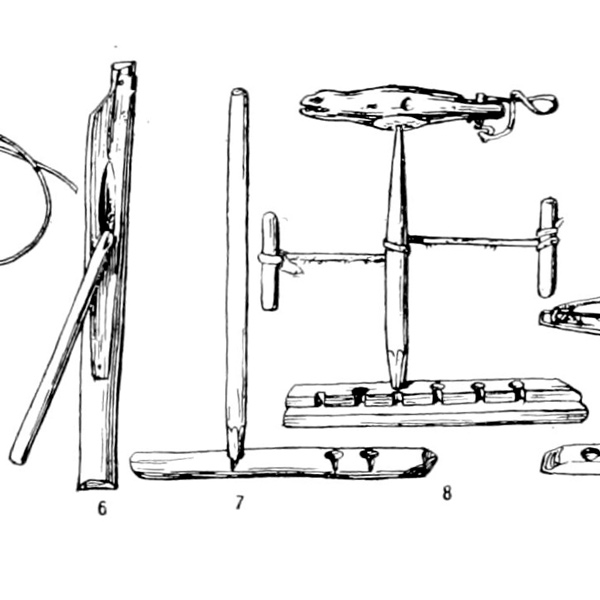

No. 6. Fire plow. Blunt stick worked along a groove in a lower stick. Polynesians

No. 7. Fire drill. Slender rod twirled between the hands upon a lower stick having a cavity with slot. Indians of the United States and widely diffused in the world

No. 8. Fire drill. Rod held in a socket and gyrated by means of a cord. The lower piece of wood has a cavity with slot, opening upon a shelf. Eskimos of Alaska

When the members of the Lewis and Clark Expedition crossed the continent their lives were ruled by the four ancient elements. Their journal entries tell us much about earth (the landscape itself, and the provider of food and shelter), air (weather), and water (rivers, rain, and snow), but very little about fire.

Yet fire was an essential part of the explorers’ lives. They were organized into three squads, or messes, so they probably kindled at least six cooking fires during most days of the expedition.[2]Counting the officers’ mess, there were typically four separate cooking fires.—ed. The captains and other members of the party were often alone in the wilderness, and on such occasions they surely made fires for cooking, warmth, and security. One can imagine, too, the light from lodge fires dancing on their faces as they parlayed with chiefs over a ceremonial pipe.

The journals mention the occasional scarceness of timber, forcing them to resort to dried fish, sage, or buffalo dung for fuel. Although fueling a fire could be a problem, seldom does the record refer to any difficulty lighting a fire, even though the journal keepers are silent on exactly how they did it. Eldon G. Chuinard observed that “nowhere in the journals or letters of the Expedition is there a definite description of making a fire.”[3]E. G. Chuinard, M.D., The Medical Aspects of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (Fairfield, Wash.: Ye Galleon Press, Western Frontiersmen Series 19, 1979; Fourth Printing 1989), p. 199. This statement, however, is true only with reference to the corps itself—as Edmond S. Meany has pointed out, “the journals relate . . . instances of Indians obtaining fire by friction” (referring to Lewis’s entry of 23 August 1805, describing the Lemhi Shoshones‘ use of fire sticks, bow-drill, and tinder).[4]Edmond S. Meany, “Dr. Saugrain Helped Lewis and Clark,” The Washington Historical Quarterly, Vol. 22 (October 1931, p. 298. Chuinard surmised that the corps’ fire-makers “may have used the old Indianwood-friction method, or a magnifying glass when the sun was shining,” but probably they preferred “flints and gun powder.”

Flint and Steel

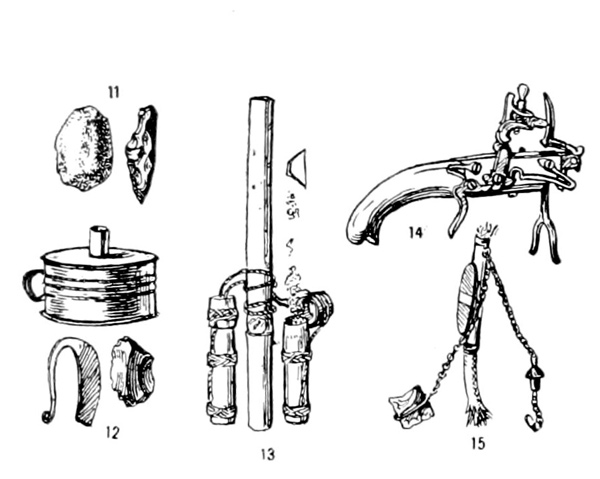

No. 11. Strike-alight. Flint and iron pyrites struck together as the ordinary flint and steel. Eskimos of Alaska

No. 12. Strike-a-light. Flint and steel and box for holding flint, steel, and tinder. Sulphur-tipped splint ignited from the tinder. England

No. 13. Strike-a-light. Bamboo tube and striker of pottery used as flint and steel. Two boxes for tinder. Malay.

No. 14. Tinder pistol. Gunlock adapted for throwing sparks into tinder. England

No. 15. Strike-a-light. Combination of flint, steel, tinder, and extinguislier, for carrying in the pocket. Spain

The friction or strike matches familiar to us today were not generally available to Americans until the late 1830s.[5]Herbert Manchester, The Diamond Match Company; a Century of Service, of Progress, and of Growth, 1835-1935 (New York: Diamond Match Co., 1935), pp. 14-15. Without friction matches, the Corps of Discovery would have relied mainly on flint and steel, a technology:

known to the Romans and . . . developed in the Dark Ages along with hand-wrought steel for weapons and armor. The steel, which was curved so as to form a handle, was held in the left hand and struck with the sharp edge of the flint. Good tinder was very important and was made by charring lint, or other easily combustible material, and keeping it dry in a tinder box or pouch. The fire maker blew upon the lighted tinder to spread the fire and added shavings, or perhaps so-called matches, which then meant only splints dipped in sulphur. If everything went right, a fire was kindled in a few minutes, but the flint might have lost its sharp edge, the steel might be blunted and the tinder might be damp from rainy weather or merely from fog; moreover, as the fire was usually built in the dark before sunrise, which was the getting-up time in those days, the knuckles might be hit instead of the steel, and the fumes in-haled in ineffectual puffing.”[6]Ibid., pp. 8-9.

The above description, from a history of the Diamond Match Company, applies to a typical American house-hold of 1830, not a wilderness setting in which the fire-starter might have had to cope with damp and wind. One can imagine the expedition’s men cursing as they bent over a pile of dried moss, striking flint against steel and nursing a flame by blowing on the smoking tinder. That the corps typically used flint and steel is indicated by Lewis’s equipage list (below) and reinforced by Patrick Gass‘s journal entry of 29 August 1805, describing the “somewhat curious” Shoshone method of making fire by use of a stick-drill, which required “a few minutes” to produce a flame.[7]Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1986-99, 12 volumes), Vol. 10, p. 134. All quotations or references to journal entries in … Continue reading If Gass found the procedure “curious,” it is doubtful that this method was regularly employed by the corps.

That flint and steel was the method of choice is evident in the records of Lewis’s effort in Philadelphia in 1803 to obtain supplies and equipment for the expedition. Under the heading of “Camp Equipage,” his “List of Requirements” included “30 Steels for striking or making fire, 100 Flints [ditto].” Under the same heading he also listed other fire-making materials: “2 Vials of Phosforus, 1 of Phosforus made of allum & sugar, 12 Bunches of Small cord.” Under the heading “Indian Presents,” his list included “100 Burning Glasses, 4 Vials of Phosforus, 288 Steels for striking fire.”[8]Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (University of Illinois Press, Urbana, 1978), Vol. 1, pp. 71-72. The record further shows that Lewis requisitioned from the Ordnance Department a number of “Packg. Boxes,” including one for “Slow Match,” and “50 lbs. Best rifle powder.”[9]Ibid., pp. 92-98.

We can reasonably assume how these fire-making materials were apportioned among the members of the corps. In the case of flint and steel it seems likely that each soldier carried his own in a pouch, enabling him to start a fire for warmth or cooking when separated from the main party (as Lewis, Clark, Drouillard, Shannon, and others were from time to time). The designated mess cooks would have used their flint-and-steel kits in the morning and evening and occasionally at mid-day (though by the Detachment Order of 26 May 1804, “no cooking will be allowed in the day while on the ma[r]ch”). The corps’ three sergeants were specifically exempt from making fires or cooking, but like the captains they must have carried their own flint and steel. The other fire items—the vials of phosphorous, cord, extra flints, and the mysterious “slow” matches—would have been stored for use when needed.

“Slow Matches” and “Lucifers”

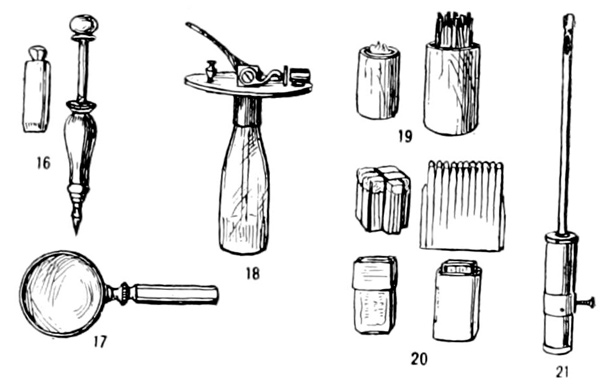

No. 16. Fire syringe. Cylinder with closely fitting piston bearing tinder. Driving the piston down smartly kindles the tinder. Siamese and Malays

No. 17. Lens. Used for producing fire by focusing sunlight upon tinder. Ancient Greeks

No. 18. Hydrogen lamp. Hydrogen gas is made, to play upon spongy platinum, causing it to glow, Germany, 1824

No. 19. Match light box. Bottle of sulphuric acid, into which splints tipped with chlorate of potash and sugar were dipped. Vienna, 1809

No. 20. Matches. Various kinds of phosphorus matches

No. 21. Electric gas lighter. Cylinder containing a small dynamo run by pres-sure of the finger, producing sparks between the points at the upper end of the tube. United States, 1882[10]Illustrations and text labels from Walter Hough (1922). Synoptic series of objects in the United States National Museum illustrating the history of inventions. Proceedings of the United States … Continue reading

References in the journals to so-called slow matches are couched in the term “port fire” (usually spelled “portfire”), a type of fuse used to ignite a cannon. In the University of Nebraska Press edition of the journals, editor Gary Moulton describes this item as “a slow-burning fuse, probably a cord impregnated with gunpowder or some other flammable substance.”[11]In the parlance of the early 1800s “slow” or portfire matches related to gunnery or artillery accessories. (They were “slow” because they burned slowly; “port” … Continue reading In Clark’s description of the corps’ confrontation with the Teton Sioux on 28 September 1804, he states that he “took the port fire from the gunner” manning the keelboat‘s swivel cannon. A year and a half later, on 2 April 1806, Clark averted a confrontation with a group of Indians on the Willamette with a bit of magic involving a “Small pece of port fire match.” (LINK More on this later.)

Based on some tantalizing if indirect evidence, some historians have asserted that the Corps of Discovery, at least on occasion, used phosphorus-based friction matches, also known in the parlance of the day as “lucifers.” Meany refers to Mrs. Eva Emery Dye (writing in 1902), who declared that Lewis and Clark had matches that “were struck on the Columbia a generation before Boston or London made use of the secret.”[12]Meany, pp. 295-96, referring to Eva Emery Dye, The Conquest (A.C. McClurg & Co., 1902), Chapter 5. Chuinard notes a reference from Henry M. Brackenridge (writing in 1834) claiming that “while the rest of the world was using flint and steel, Lewis and Clark were able to strike matches far out on the Columbia River.”[13]Chuinard, pp. 198-99n9, citing William Clark Kennerly, Persimmon Hill (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1940), p. 141, and other references.

The Engaging Dr. Saugrain

Brackenridge bases this assumption on his personal knowledge of Dr. Antoine Saugrain, a peripatetic French expatriate and inventor.

Called the “First Scientist of the Mississippi Valley,”[14]Meany, p. 309, n. 24, citing W.V. Byars, The First Scientist in the Mississippi Valley, (pamphlet), pp. 14-15. Saugrain was a chemist and naturalist and the only physician in the frontier community of St. Louis when Lewis and Clark arrived there in 1803. Described by a contemporary as “a cheerful, sprightly little French-man”—he was just four-feet-six—he had been appointed by President Jefferson, after the cession of Louisiana to the United States, as the resident surgeon at Camp Bellefontaine, a nearby military post.[15]Saugrain de Vigni, Antoine Francois, 1783-1821, L’Odysee Americaine d’une Famille Francaise {par} le docteur Antoine Saugraine; H. Foure Selter, ed. (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, … Continue reading

A member of a distinguished Parisian family, Saugrain was schooled in the natural sciences and as a young man he had taken part in a mineralogical exploration in Mexico. Following the outbreak of the French Revolution, he settled with other French exiles at Gallipolis, Ohio, and later moved to Lexington, Kentucky.

The doctor was something of a showman and seems to have liked nothing better than putting on scientific demonstrations. These included placing “little phosphoric matches” in a glass tube, sucking the air out to create a vacuum, then breaking the glass—at which point the matches ignited spontaneously. He also fabricated briquets phosphoriques—phosphorous “lighters”—and experimented with electricity, repeating the famous kite experiment of his friend Benjamin Franklin, whom he had met years before while visiting Philadelphia.[16]Ibid., pp. 3-67.

By 1800 Saugrain was settled in St. Louis.14 Three years later he met Meriwether Lewis. “It is inconceivable,” writes Meany, “that Captain Lewis was not familiar with Dr. Saugrain’s hobbies and vocation or that he was not frequently welcomed in the Doctor’s home and laboratory.”[17]Meany, p. 310. Given Saugrain’s eminence as a naturalist and physician, both Lewis and Clark doubtless consulted with him during their five months at Camp Dubois. The colorful doctor’s bag of tricks included “lucifers,” and it is reasonable to assume that he gave the captains at least a few of them, either for use at Camp Dubois or for later on their journey.

It is a gift that Lewis in particular would have appreciated, for his mentor, Thomas Jefferson, had been using friction matches since at least 1784, when he wrote to his friend Charles Thompson

I should have sent you a specimen of the phosphoric matches . . . . They are a beautiful discovery and very useful, especially to heads which, like yours and mine, cannot at all times be got to sleep. The convenience of lighting a candle without getting out of bed, of sealing letters without calling a servant, of kindling a fire without flint, steel, punk, c., is of value.[18]The Jeffersonian Cyclopedia, No. 5138, p. 544.

Lewis would doubtless have shared the President’s enthusiasm for friction matches while the two men lived together in the White House, and the possibility of making “lucifers” in the field may be one reason he included phosphorus in the provisions he gathered in Philadelphia.

The journals’ single reference to the vials of phosphorus Lewis acquired in Philadelphia comes late in the expedition, when the explorers were preparing to re-cross the Rockies on the homeward leg of their journey. On 2 June 1806, Lewis gave McNeal and York some items for trading with Indians—buttons, eye water, basilicon, and “some Phials and small tin boxes which I had brought out with phosphorous.” It’s not clear if the vials still contained phosphorus or if Lewis had used it. If so, how? The journals are silent. As suggested, the captains may have made friction matches with it. They may also have used it to make portfire.

Magic on the Willamette

Clark made clever use of portfire—perhaps impregnated with phosphorus—on 2 April 1806, when he parlayed with a group of Indians over a lodge fire near the banks of the Willamette River. He wanted to trade with them for wappato roots, but noted in exasperation that they “positively refused.” He describes what happened next:

I had a Small pece of port fire match in my pocket, off of which I cut . . . a pece one inch in length & and put it into the fire and took out my pocket Compas and Set myself doun on a mat on one Side of the fire.

Clark also took out a magnet in the top of his ink stand. The portfire caught and “burned vehemently,” changing the color of the fire. With his magnet Clark then “turned the needle of the Compas about very briskly; which astonished and alarmed these nativs and they laid Several parsles of Wappato at my feet, & begged of me to take out the bad fire.”[19]To James Ronda, such “technological wizardry” had a “grimmer side.” As he notes, Clark’s intimidation of women, children, and an old man suggests a “willingness to … Continue reading

The key feature in this incident seems to have been the “bad” color in the fire. Unfortunately, Clark doesn’t specify the exact color. Could it have been the blue light of burning phosphorus? It seems probable, for since its discovery in 1669, phosphorus had long been regarded as a “miraculous chemical” for the “cold light” of its flame.[20]Edward Farber, “History of Phosphorous,” U.S. National Museum Bulletin 240, Paper 40 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1965), p. 178.

On the other hand, if the portfire had been impregnated with black powder (made from charcoal, saltpeter, and sulfur, a first cousin to phosphorus in the Table of Elements) the color would have been yellow-orange. That, at least, was the color a friend of mine, Stuart Harris of North Bend, Washington, got when he experimented with portfire in his back yard. With Clark on the Willamette in mind, Harris ignited a thimble full of black powder, resulting in a cloud of gray smoke and a yellowish-orange flash.

Because yellow-orange is closer to the color of a wood fire and would not, therefore, have had the same impact as a cold blue flame, perhaps phosphorus was the magic ingredient in Clark’s portfire. In the minds of the Indians, however, it may have been the association of two acts of magic—the moving compass and the flaming cord—that made the color “bad.”

Alas, the silence of the journals on this and other imponderables of the Lewis and Clark Expedition re-calls a remark made by Antoine Saugrain to his daughter during an experiment in the doctor’s laboratory: “We are working in the dark, my child. I only know enough to know that I know nothing.”[21]Meany, p. 307; L’Odysee, p. 35.

Notes

| ↑1 | Robert R. Hunt, “Making Fire: Matches and Magic,” We Proceeded On, Volume 26, No. 3 (August 2000), the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. The original printed format is provided at lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol26no3.pdf#page=14. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Counting the officers’ mess, there were typically four separate cooking fires.—ed. |

| ↑3 | E. G. Chuinard, M.D., The Medical Aspects of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (Fairfield, Wash.: Ye Galleon Press, Western Frontiersmen Series 19, 1979; Fourth Printing 1989), p. 199. |

| ↑4 | Edmond S. Meany, “Dr. Saugrain Helped Lewis and Clark,” The Washington Historical Quarterly, Vol. 22 (October 1931, p. 298. |

| ↑5 | Herbert Manchester, The Diamond Match Company; a Century of Service, of Progress, and of Growth, 1835-1935 (New York: Diamond Match Co., 1935), pp. 14-15. |

| ↑6 | Ibid., pp. 8-9. |

| ↑7 | Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1986-99, 12 volumes), Vol. 10, p. 134. All quotations or references to journal entries in the ensuing text are from Moulton, Volumes 2-11, by date, unless otherwise indicated, without further citation. |

| ↑8 | Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (University of Illinois Press, Urbana, 1978), Vol. 1, pp. 71-72. |

| ↑9 | Ibid., pp. 92-98. |

| ↑10 | Illustrations and text labels from Walter Hough (1922). Synoptic series of objects in the United States National Museum illustrating the history of inventions. Proceedings of the United States National Museum 60 (2404). 1-47, 56 pl. |

| ↑11 | In the parlance of the early 1800s “slow” or portfire matches related to gunnery or artillery accessories. (They were “slow” because they burned slowly; “port” referred to the opening in the cannon in which the fuse was inserted.) The Oxford English Dictionary (second edition; Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989; Vol. 15, p. 747) citing “James Milit Hist,” 1802, states that the slow match is “made of hemp, or tow, spun on the wheel like cord, but very slack, and . . . composed of three twists.” The OED under its entry for “match” (Vol. 9, p. 458) notes that the slow match is “so prepared that when lighted at the end it is not easily extinguished, and continues to burn at a uniform rate; used for firing cannon or other fire-arms, and for igniting a train of gunpowder . . . burns at the rate of one yard in three hours.” |

| ↑12 | Meany, pp. 295-96, referring to Eva Emery Dye, The Conquest (A.C. McClurg & Co., 1902), Chapter 5. |

| ↑13 | Chuinard, pp. 198-99n9, citing William Clark Kennerly, Persimmon Hill (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1940), p. 141, and other references. |

| ↑14 | Meany, p. 309, n. 24, citing W.V. Byars, The First Scientist in the Mississippi Valley, (pamphlet), pp. 14-15. |

| ↑15 | Saugrain de Vigni, Antoine Francois, 1783-1821, L’Odysee Americaine d’une Famille Francaise {par} le docteur Antoine Saugraine; H. Foure Selter, ed. (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1936), p.33. |

| ↑16 | Ibid., pp. 3-67. |

| ↑17 | Meany, p. 310. |

| ↑18 | The Jeffersonian Cyclopedia, No. 5138, p. 544. |

| ↑19 | To James Ronda, such “technological wizardry” had a “grimmer side.” As he notes, Clark’s intimidation of women, children, and an old man suggests a “willingness to bend the rules whenever it suited the expedition’s need.” See James P. Ronda, Lewis and Clark Among the Indians (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1984), p. 216. Yet one may reasonably ask whether this situation differs basically from many other occasions throughout the journey when Lewis and Clark exhibited other scientific wonders—the air gun, magnifying glasses, compass, magnet, etc—to Indians to enhance a mood for trade and a sense of primacy in a potentially hostile environment. |

| ↑20 | Edward Farber, “History of Phosphorous,” U.S. National Museum Bulletin 240, Paper 40 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1965), p. 178. |

| ↑21 | Meany, p. 307; L’Odysee, p. 35. |