A Suitable Location

The party wanted salt for flavoring, and needed it for curing meat. No one mentioned it, but they also would rub it into the insides of elk hides to draw moisture out, in preparation for making much-needed clothing and moccasins. On 28 December 1805 the officers detailed three enlisted men—Joseph Field, William Bratton and George Gibson—to proceed to the Ocean and “at Some Convenient place form a Camp and Commence makeing Salt with 5 of the largest Kittles.” Their temporary camp that would have to be somewhat sheltered from winter winds, near to winter deer and elk range, and as far south of the estuary as it could be without requiring them to climb over or around Tillamook Head. It had to be reasonably close to the ocean where seawater—which ancient proto-scientists had regarded as the “sweat of the earth”—could be processed for salt, and correspondingly close to a plentiful source of firewood.

Why didn’t they just set up camp on the Netul River? Well, ocean tides did reach some 30 miles upriver, and more or less affected the salinity of the Netul River (now called the Lewis and Clark River), which was only five miles up the estuary. But the mixture of fresh river water with salt water, introducing between 3 and 5 grams of dissolved salts per litre created a brackish soup ranging between 0.05% to 3% of dissolved salts–not enough for efficient extraction of salt. The crew had to find a place on the coast well away from dilution by the outflow from the Columbia River and “Commence making Salt.”

Making Salt

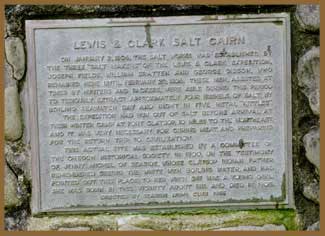

Properly speaking, a cairn, is a mound of rocks erected as a memorial or marker. The so-called “Salt Cairn” pictured here represents a reasonable guess as to the appearance of the oven the salt makers built.

Willard and Weiser were sent along to help carry the Corps’ five largest kettles. After five days of exploration they finally decided on a location on the beach about 17 miles below the mouth of the Columbia. There was plenty of firewood and fresh water nearby, and several families of congenial Tillamook Indians were their nearest neighbors.

Back at the fort, the rest of their party was without salt for another nine days while the salt camp crew set up camp and got their salt works into gear. Finally, on 5 January 1806 Alexander Willard and Peter Weiser returned with a gallon of sea salt, representing a good day’s production. Lewis found it “excellent, fine, strong, & white.” Clark felt that it was “not So Strong as the rock Salt or that made in Kentucky or the Western parts of the U.States.”

For a month and a half the detail kept the fires going day and night, lugged a total of perhaps 1,400 gallons of water from the surf, and boiled it down to 28 gallons of salt. Twelve gallons, packed in two small ironbound kegs, were set aside for the return trip as far as the mouth of the Marias River, where they had cached a reserve supply.

Today’s Memorial

The site of the salt works, a detached section of Fort Clatsop National Memorial, is now surrounded by a residential district in the resort town of Seaside, Oregon.

By 1900 the salt makers’ oven had long since collapsed into a pile of rocks—a “cairn.” In the 1950s, local historians reassembled the stones into a structure that represents the presumed appearance of the original.

The plaque reads:

On 2 January 1806, the salt works was established by the three “salt makers” of the Lewis & Clark Expedition: Joseph Fields [sic], William Bratten and George Gibson, who remained here until 20 February 1806. These men, assisted at times by hunters and packers, were able during this period to tediously extract approximately four bushels of salt by boiling seawater day and night in five metal “kittles.”

The Expedition had run out of salt before arrival at their winter camp at Fort Clatsop, 10 miles to the northeast, and it was very necessary for curing meat and preparing for the return trip to civilization.

This actual site was established by a committee of the Oregon Historical Society in 1900, on the testimony of Jenny Michel of Seaside, whose Clatsop Indian father remembered seeing the white men boiling water, and had pointed out this place to her when she was a young girl. She was born in this vicinity about 1816 and died in 1905.

Erected by Seaside Lions Club 1955.