Before and During the Expedition

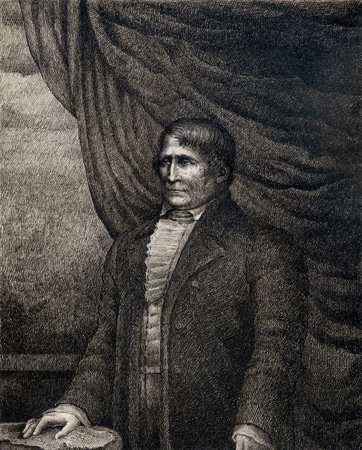

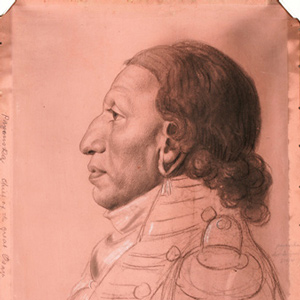

Payouska (White Hair, c. 1752-1832)

Chief of the Great Osage (1804)

New-York Historical Society, 1860.92.

In Washington City, Charles B. J. F. de Saint Mémin, (1770–1852), painted four of the Osages traveling with Pierre Chouteau. Here, Payouska dons an Indian peace medal and military uniform coat (see Uniforms).[1]William R. Swagerty, The Indianization of Lewis and Clark (Norman, Oklahoma, The Arthur H. Clark Company, 2012), 2:620–21.

The Osage were experienced traders, exchanging horses and Indian slaves for French guns, knives, axes, kettles, and other metal objects. When the Spanish assumed control of Louisiana in the 1760s, authorities banned trading for slaves, and the Osage adopted a new economic system of planting gardens in permanent villages, hunting in the plains while the crops grew, and trapping beaver, otter and other animals for the hide and fur trade in the winter fur-bearing months. At the time of the expedition, increased competition for hunting lands between Algonquian peoples such as the Sauks and Foxes, Lenape Delawares, Kickapoos, Potawatomis, Shawnees, and Illinois tribes created clashes, a trend that would increase through the 18th century.[2]Frederick Webb Hodge, Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico, Vol. 2 (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology, Government Printing Office, 1910), 157–58; Garrick A. … Continue reading

When the first Europeans landed in New England the tribe lived in the Ohio River valley. It consisted of two bands, the Wazhazhe or meat-eaters, and the Tsishu or vegetarians. When the first delegation of Osage chiefs met with Jefferson in 1804, their homes were near the forks of the Osage River. Their homeland extended from the Missouri River on the north to the Arkansas River on the south, and from the Mississippi to the Great Plains. Meriwether Lewis, in fact, sent a map of it to Jefferson from Fort Mandan in the spring of 1805.

The challenges confronting the Osage People were somewhat understood by Lewis and Clark, probably because of their working relationship with traders Auguste and Pierre Chouteau. The influential St. Louis family had worked for years for the right to trade with the Osage—struggling not with the Osage so much as three different Spanish governors whose various decrees were often at odds with Chouteau family’s ambitions. With the transfer of Louisiana to the United States, the Chouteaus saw an opportunity to regain an exclusive monopoly, and their cooperation, influence and help with the Lewis and Clark Expedition was immeasurable. While wintering at their camp on the Wood River, the captains worked with the Chouteaus to form a delegation bound for Washington City, and on 19 March 1804, they joined together to intercept a Kickapoo war party bound for the Osage.

Clark, the future agent for the privately held Missouri Fur Company, governor of Missouri Territory, and Superintendent of Indian Affairs, suggested in the expedition’s 1805 “Estimate of the Eastern Indians,” the following path forward for the Osage:

There is no doubt but their trade will increase: they could furnish a much larger quantity of beaver than they do. I think two villages, on the Osage river, might be prevailed on to remove to the Arkansas, and the Kansas, higher up the Missouri, and thus leave a sufficient scope of country for the Shawnees, Dillewars, Miames, and Kickapoos.[3]Moulton, Journals, 3:391.

Tixier’s Description

Meriwether Lewis had no personal contacts with any Osage Indians until he returned to St. Louis after the expedition. Consequently, detailed descriptions of the Osages’ appearance like those he wrote of the Mandan, Lemhi Shoshone, Nez Perce, and Clatsop had to await the visit of Victor Tixier (1815-1885), a French physician who spent a year in America more than 30 years later. The description of the Osage men in his Voyage aux prairies osages, Louisiane et Missouri, 1839-40 were fully as thorough as Lewis’s would have been, and they show that the Osage nation still was as strong and viable as when Jefferson had entertained their leaders:

The men are tall and perfectly proportioned. They have at the same time all the physical qualities which denote skill and strength combined with graceful movements. . . .

. . . their ear[lobe]s, slit by knives, grow to be enormous, and they hang low under the weight of the ornaments with which they are laden. There is a complete lack of beard and eyebrows on their faces, for they carefully pull out the little hair which happens to grow there.

Their calm, dignified faces show great shrewdness; there is something soldierly and serious about the expression. Their hair is black and thick. The Osage shave their heads, except for the top, from which two strands of hair branch off and grow straight back to the occiput, where they form a tuft which falls to the lower part of the neck; between these strands grow two braids, the beauty of which consists in their length. . . .

The [Osage Indians] seldom go out without painting themselves; the colors they use are, first, vermillion, then verdigris [greenish-blue], and then yellow, which they buy from the trader; lacking these, they use ochre, chalk, or even mud. . . . The Osage always paint red that part of their head around their hair, the eye-sockets, and their ears; these are the national colors, the war-time paint. The other colors, indifferently put on the other parts of their bodies, depend upon their individual fancy.[4]John Francis McDermott, editor, and Albert J. Salvan, translator, Tixier’s Travels on the Osage Prairies, 1844 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1940), 136-37.

After the Expedition

After the expedition, both Clark and Lewis would spend much time negotiating with the Osage. Just months after the expedition’s end on 26 September 1806, Lewis was appointed governor of Upper Louisiana Territory and Clark agent to all Indians west of the Mississippi. The agent for the Osage, however, was assigned to Pierre Chouteau. In 1808, Clark wrote his first Indian treaty in which he, in the words of historian Jay Buckley, “extorted” a huge land concession from Chief White Hair of the Osage. Clark received further land cessions from the Osage in 1818 and 1825.[5]Jay H. Buckley, William Clark: Indian Diplomat (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010), 76, 169; Bailey, 477.

In the 1830s and 1840s, the Osage adapted by becoming participants in the buffalo robe trade. During this period, the last people were moved to a reservation in Kansas. In the 1890s, oil was discovered there, and a decade later, the 1906 Osage Allotment Act sought dissolve the reservation. The tribe retained all mining rights and dispersed the land only to tribal members except for infrastructure such as villages, schools, and railroads. Revenue from mineral leases in 1923 alone netted each tribal member $12,400.[6]Bailey, 489.

In 2004, the Osage regained their legal status as a sovereign nation. At the time, their reservation was technically considered to still exist, but a 2010 Federal court decided that it had been dissolved with the Osage Allotment Act of 1906. Today, the Osage Nation has over 13,000 enrolled members with just over half living in Oklahoma. The tribal government is headquartered in Pawhuska, Oklahoma and has jurisdiction in Osage County.[7]“Osage Nation,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Osage_Nation, accessed 16 January 2021.

Selected Pages and Encounters

The Osage Delegations

by Joseph A. Mussulman

They were “certainly the most gigantic men we have ever seen,” Jefferson wrote on 12 July 1804. A dozen Osage men and two boys had arrived in Washington City the previous day, escorted by Pierre Chouteau.

December 25, 1803

Wood River Christmas

At Wood River, the men celebrate Christmas by drinking, hunting, and frolicking. Visiting Indians share a rumor regarding Louisiana trade, and interpreter and hunter George Drouillard agrees to join.

February 18, 1804

An Osage delegation

From Wood River, Lewis works with St. Louis fur trader Pierre Chouteau to send a delegation of Osage to Washington City. In a letter, Lewis encourages Chouteau to take the group himself.

February 20, 1804

Working in St. Louis

Based on his letter of 18 February, Lewis likely follows through on his promise to join Clark in St. Louis today. There, he helps Pierre Chouteau organize an Osage delegation bound for Washington City.

March 19, 1804

Intercepting a war party

Clark and Lewis travel to St. Charles to prevent a large Kickapoo war party from attacking the Osage. The enlisted men continue at Wood River, Illinois under Sgt. Ordway’s charge.

March 21, 1804

Return to Wood River

Lewis, Clark, Auguste or Pierre Chouteau, and Charles Gratiot return to Wood River, Illinois after intercepting a Kickapoo war party near St. Charles. Clark’s field notes resume—the first since 9 February.

April 21, 1804

Chouteau's Osage delegation

Across the Mississippi, a cannon is heard and soon after 22 Osage Indians arrive escorted by trader Pierre Chouteau. The captains accompany the delegation to St. Louis leaving Sgt. Ordway in charge.

May 3, 1804

Chouteau's Osage delegation

From St. Louis and Camp River Dubois, Lewis and Clark write letters of introduction for Pierre Chouteau who will soon take a delegation of Osage to Washington City. Trader Manuel Lisa visits Clark.

May 17, 1804

St. Charles court martial

Privates Hugh Hall and John Collins misbehaved in St. Charles the previous night and today face a court martial. Some visiting Kickapoos tell Clark that the Sauk and Osage are at war—a thing the captains have been trying to prevent.

May 27, 1804

Gasconade River

The flotilla meets two trading parties coming down from Omaha and Osage villages. At evening camp near the mouth of the Gasconade River in present Missouri, arms and ammunition are inspected.

May 31, 1804

Osage disbelief

Strong winds force the expedition to remain near present-day Chamois, Missouri. Some traders heading down report that the Osage People do not believe that their homeland is now part of the United States.

June 1, 1804

Mouth of the Osage

After a hard day, the expedition stops at the mouth of Osage River where the captains make celestial observations late into the night. Lewis also collects a specimen of wild ginger, Asarum canadense.

June 8, 1804

The Lamine River

During the day, they meet three French traders coming down the river who are out of provisions and powder. They learn that lead ore has been found along the Lamine (The Mine) River.

June 15, 1804

Dangerous Missouri river

The men struggle to move the boats against the strong Missouri current with submerged logs and crumbling banks. They camp opposite old Little Osage and Missouria villages at present Malta Bend.

July 16, 1804

Stuck on a sawyer

The expedition sails twenty miles up the Missouri River and camps near a ‘Bald Pated’ prairie at the Nishnabotna River. In Washington City, President Jefferson addresses a visiting Osage delegation.

November 5, 1804

Raising the huts

The day is spent raising Fort Mandan cabins and splitting boards for the cabin lofts. Mandan hunters report capturing 100 pronghorns, Clark’s rheumatism continues, and Lewis spends the day writing.

January 4, 1806

Across the Clatsop Plain

Sgt. Gass and Pvt. Shannon travel through the marshes and dunes of the Clatsop Plain on their way to the salt makers’ camp. At Fort Clatsop, Lewis describes Clatsop views on material goods.

Notes

| ↑1 | William R. Swagerty, The Indianization of Lewis and Clark (Norman, Oklahoma, The Arthur H. Clark Company, 2012), 2:620–21. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Frederick Webb Hodge, Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico, Vol. 2 (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology, Government Printing Office, 1910), 157–58; Garrick A. Bailey, Handbook of North American Indians: Plains Vol. 13, ed. Raymond J. DeMallie (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 2001), 476. |

| ↑3 | Moulton, Journals, 3:391. |

| ↑4 | John Francis McDermott, editor, and Albert J. Salvan, translator, Tixier’s Travels on the Osage Prairies, 1844 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1940), 136-37. |

| ↑5 | Jay H. Buckley, William Clark: Indian Diplomat (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010), 76, 169; Bailey, 477. |

| ↑6 | Bailey, 489. |

| ↑7 | “Osage Nation,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Osage_Nation, accessed 16 January 2021. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.