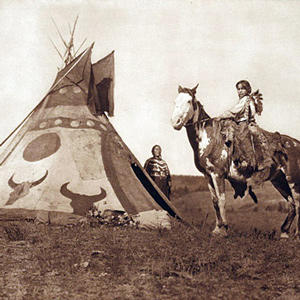

A Skin Lodge of an Assiniboin Chief

Karl Bodmer (1809–1893)

Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library.[1]“Lederzelt eines Assiniboin Chefs. Tente en cuir d’un chef Assiniboin. A skin lodge of an Assiniboin chief.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed March 14, 2019. … Continue reading

The Assiniboins or Assiniboines are sometimes called the Stone Sioux, Hohe, and Nakota or Nakoda Sioux. Lewis spelled Assiniboine—the name was not only a native nation but a well-known river in Canada—at least seven different ways. In the “Estimate of the Eastern Indians,” Clark describes three bands:

Manetopa [Crane or Canoe]. Oseegah [Girls]. Mahtopanato [Big Devils]. Are the descendants of the Sioux, and partake of their turbulent and faithless disposition: they frequently plunder, and sometimes murder, their own traders. The name by which this nation is generally known was borrowed from the Chippeways, who call them Assinniboan, which, literally translated, is Stone Sioux, hence the name of Stone Indians, by which they are sometimes called.[2]Moulton, Journals, 3:432. Band name translations, in brackets, provided by Douglas R. Parks, Handbook of North American Indians: Plains Vol. 13, ed. Raymond J. DeMallie (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian … Continue reading

At the time of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, the Assiniboines were nomadic hunter-gatherers roaming primarily along the rivers in Saskatchewan and western Manitoba. They often dropped south into present-day Montana and North Dakota, especially in their role as middle-men between the English trading companies and the Hidatsas to the south. That trade relationship become critical when in 1777, the establishment of Hudson’s House near Atsina territory ended their trade relationships with the Blackfeet and Atsinas to the west.[3]Raymond J. DeMallie and David Reed Miller, Handbook of North American Indians: Plains, 574.

While building Fort Mandan, the captains met Chief Chechank and seven other Assiniboines who had come to trade among the Knife River Villages:

at 10 oClock A M the Black Cat the Mandin Chief and Lagru Che Chark Chief & 7 men of note visited us at Fort Mandan, I gave him a twist of Tobacco to Smoke with his people & a Gold Cord with a view to Know him again

—William Clark, 13 November 1804[4]Apparently the French called him La Grue, French for “The Crane” and his native name was Chechank, meaning “old crane.” Moulton, Journals, 3:235; James P. Ronda, Lewis and … Continue reading

Notable in their exchange with Chief Chechank is that the Assiniboines were not given the standard diplomatic speech, Indian presentation flag, or peace medals. Although Jefferson and Lewis hoped the boundaries of the Louisiana Purchase extended north of the 49th Parallel,[5]Lewis took on a great risk when left the Great Falls of the Missouri to locate the source of the Marias River. It did not lead him north of the 49th Parallel, but did lead him to a fatal encounter … Continue reading they knew the rivers most frequented by the Assiniboine flowed into Hudson Bay. Thus, they were subjects of the British crown, not the United States. As such, the captains hoped to create a favorable impression with a gift of tobacco and a gold cord.

Five days later, on 18 November 1804, Posecopsahe (Black Cat) told of a Mandan council to consider whether to stop trading with the bothersome Assiniboine and instead rely on the trade goods from St. Louis promised by the captains. Citing the unfulfilled promises of John Evans in 1796, the Mandans were inclined to continue with the Assiniboines rather than risk another broken promise. The devil you know is safer than the angel you don’t, perhaps.[6]For a fuller analysis of the implications the expedition had on Assiniboine trade, see Ronda, 89–90.

The meeting on 13 November 1804 would be the expedition’s only direct encounter with Assiniboines. The captains did, however, continue to hear stories and see signs of their presence. On 4 March 1805, they were told how an Assiniboine trading envoy transformed into a horse raid at one of the nearby Hidatsa villages.

On 8 May 1805, while traveling along the Missouri’s Northern Reach, they came across the place where an Indian had removed the hair from a pronghorn antelope skin. Lewis stated: “we do not wish to see those gentlemen just now as we presume they would most probably be the Assinniboins and might be troublesome to us.” Given the threat the Americans posed to remove the Assiniboines as middle-men in the European trade, perhaps it was lucky more encounters were not forthcoming.

Today, some Assiniboines are members of the Fort Peck Assiniboine-Sioux Tribe, Fort Peck Reservation; others belong to the Gros Ventre & Assiniboine Tribes, Fort Belknap Reservation. The two speak similar, but distinct dialects of the Assiniboine language. In Canada, many are members of various First Nations groups in Saskatchewan, Canada where both dialects can also be found.[7]DeMallie and Miller, 572.

Selected Pages and Encounters

Montana’s Indian Country

Changes after the expedition

by Rick Newby

Beginning with the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, the U.S. government set the vast area north of the Missouri (approximately 20 million acres) aside as the “Blackfeet Hunting Ground” for the Blackfeet and other tribes—Cree, Assiniboine, Gros Ventre, and Sioux.

Flag Presentations

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Lewis and Clark usually distributed flags at councils with the chiefs and headmen of the tribes they encountered—one flag for each tribe or independent band.

October 25, 1804

Curious Mandans

The expedition continues up the Missouri River above present Washburn, North Dakota. Finding a good channel becomes difficult, and they hear news of Sioux and Assiniboine raids and a killing.

November 5, 1804

Raising the huts

The day is spent raising Fort Mandan cabins and splitting boards for the cabin lofts. Mandan hunters report capturing 100 pronghorns, Clark’s rheumatism continues, and Lewis spends the day writing.

November 13, 1804

Ice waters

At Fort Mandan, the barge is threatened by ice, and Clark learns about the Assiniboine People. Lewis returns late after spending two hours in the river dragging a pirogue loaded with chimney stones.

November 16, 1804

Moving into the huts

At Fort Mandan, the morning brings thick frost. Fortunately, the enlisted men can move from their tents into unfinished cabins. The captains learn of a dispute between Assiniboines and their Hidatsa hosts.

November 18, 1804

Blackcat visits

At Fort Mandan, Black Cat’s wife brings as much corn as she can carry. Blackcat tells the captains that the Mandans have decided to continue with the Canada-based traders rather than St. Louis.

December 26, 1804

The good old game

A North West Company trader comes to Fort Mandan to hire Charbonneau as a translator. Clark learns that a Hidatsa attempt to retrieve stolen horses was somewhat successful, and Lewis plays backgammon.

January 25, 1805

Assiniboine traders

At Fort Mandan, the enlisted men continue making charcoal for the blacksmiths and trying to free the boats from the Missouri River ice. At the Knife River Villages, a band of Assiniboine traders arrives.

March 10, 1805

Hidatsa migration

Black Moccasin and another Hidatsa—likely White Buffalo Robe Unfolded visit Fort Mandan. They tell the captains how the Mandans and Hidatsas were decimated by wars and smallpox and then banded together.

April 12, 1805

Little Missouri River

Early in the day, a crumbling bank threatens the red pirogue. They spend most of the day at the Little Missouri River and see beaver, empty Assiniboine camps, creeping juniper, and wild onions.

April 13, 1805

The white pirogue's near miss

Below present Van Hook Arm, North Dakota, a sudden gust of wind hits the white pirogue with Charbonneau at the helm. In his panic, he turns the boat sideways to the wind and nearly turns it over.

April 14, 1805

Bear Den Creek

Bear Den Creek, ND Passing sage-covered hills, the expedition makes fourteen miles up the Missouri River. They notice prairie dogs, elk, buffalo and two empty Assiniboine camps.

April 17, 1805

Smooth sailing

With a tailwind, the boats make nearly 26 miles up the Missouri River. Lewis comments on his preference for beaver tail and liver. Camp is above present Lewis and Clark State Park in North Dakota.

April 20, 1805

An Assiniboine grave

Below present Williston, North Dakota, hard winds prevent the boats from making more than seven miles up the Missouri. Lewis walks on shore and observes a partially fallen Assiniboine scaffold grave.

May 2, 1805

Beaver tails

The morning brings an inch of new snow and with the day’s high winds, they move less than five miles to a camp southeast of present Poplar, Montana. Lewis esteems the flesh of the beaver a delicacy.

May 4, 1805

Rudder repairs

On their way to evening camp east of present Wolf Point, Montana, Lewis describes empty Indian hunting camps and treats Pvt. Joseph Field with salts and opium. They also see vast herds of bison.

May 8, 1805

The 'River that Scolds all Others'

Clark explores the Milk River, and Sacagawea brings him breadroot, an important Indian food source. After finding recent Assiniboine activity, Lewis wishes to avoid any encounter with that Tribe.

May 10, 1805

Describing mule deer

After five miles struggling against the Missouri’s current near present Fort Peck, Montana, high winds stop the boats. When an Indian dog appears at camp, the soldiers scout the hills and inspect arms.

July 4, 1806

Dangerous roads

Lewis travels east on “Cokahlahishkit”—the Road to the Buffalo—along the Blackfoot River. Clark travels south up the Bitterroot River and celebrates the Fourth of July with a “Sumptious Dinner”.

August 11, 1806

Cruzatte shoots Lewis

Lewis is shot through the buttock. An Indian attack is suspected, but likely Pvt. Cruzatte mistook him for an elk. Clark meets fur traders who share news of the barge, the fur trade, and Indian wars.

Notes

| ↑1 | “Lederzelt eines Assiniboin Chefs. Tente en cuir d’un chef Assiniboin. A skin lodge of an Assiniboin chief.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed March 14, 2019. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-c3fe-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Moulton, Journals, 3:432. Band name translations, in brackets, provided by Douglas R. Parks, Handbook of North American Indians: Plains Vol. 13, ed. Raymond J. DeMallie (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 2001), 593. |

| ↑3 | Raymond J. DeMallie and David Reed Miller, Handbook of North American Indians: Plains, 574. |

| ↑4 | Apparently the French called him La Grue, French for “The Crane” and his native name was Chechank, meaning “old crane.” Moulton, Journals, 3:235; James P. Ronda, Lewis and Clark among the Indians (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1984), 89. |

| ↑5 | Lewis took on a great risk when left the Great Falls of the Missouri to locate the source of the Marias River. It did not lead him north of the 49th Parallel, but did lead him to a fatal encounter with the Blackfoot. See on this site The Marias River Risk, Blackfeet, and Fight on the Two Medicine. |

| ↑6 | For a fuller analysis of the implications the expedition had on Assiniboine trade, see Ronda, 89–90. |

| ↑7 | DeMallie and Miller, 572. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.