As attested in the writings of several key figures in the American West, Jean Baptiste Charbonneau‘s European experiences were the capstone of an education that started in a Hidatsa village and developed in St. Louis under the sponsorship of William Clark.

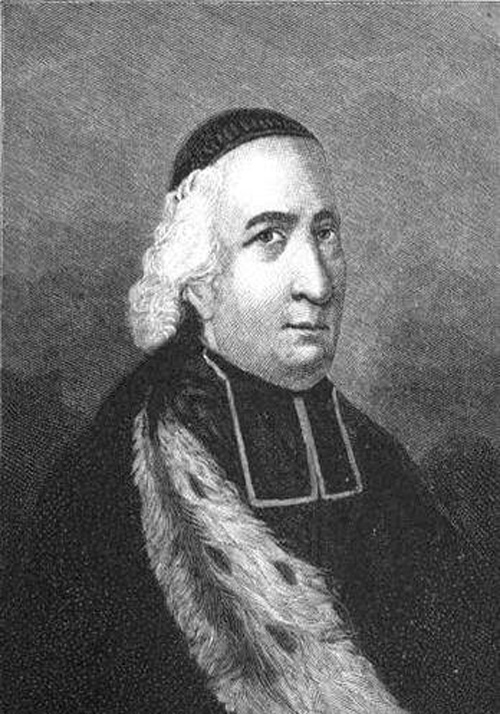

Duke Paul Meets Bishop DuBourg

Paul Wilhelm, Duke of Württemberg (1797–1860), nephew of the future King Friedrich I, was 25 years old when he met Bishop DuBourg[1]Found in literature as Dubourg, Du Bourg and Du Bourge. on a boat traveling from the Falls of the Ohio to St. Louis. The duke’s journal indicates the two spent considerable time in conversation:

“Upon boarding the Cincinnati I made the acquaintance of Mr. Du Bourg. then bishop of New Orleans and St. Louis . . . . one of the most revered and best informed men I had the good fortune to make in the New World . . . . His intelligent intercourse did much to make my stay on the boat and in St. Louis most pleasant.”[2]Paul Wilhelm, Duke of Württemberg, “First Journey to America in the Years 1822 to 1824,” trans. William G. Bek in South Dakota Historical Collections (State Historical Society, 1938), … Continue reading

DeBourg was returning west after visiting the U.S. Secretary of War John C. Calhoun. Calhoun had been promoting Jesuit missions and funding the establishment of Indian schools.[3]“Louis William Valentine DuBourg,” Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louis_William_Valentine_DuBourg. By this time, the Duke had likely decided to take a Native American or two back to Europe with him—a common practice then. It is possible that the idea of taking one of DuBourg’s St. Louis academy students, perhaps even Jean Baptiste, son of Toussaint Charbonneau and Sacagawea and ward of William Clark, germinated aboard the Cincinnati. At the very least, DuBourg informed the duke, apparently, of whom to see and where to go while in St. Louis.

Duke Paul in St. Louis

Duke Paul of Würrtemberg

by Franz Seraph Stirnbrand (1796–1882)

This is image is in the public domain, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Franz_Seraph_Stirnbrand_-_Herzog_Paul_von_W%C3%BCrttemberg.jpg.[4]For an alternate portrait and biography, see “Duke Paul Wilhelm of Württemberg,” Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Duke_Paul_Wilhelm_of_W%C3%BCrttemberg..

Duke Paul arrived in St. Louis in May 1823 where he met William Clark, Auguste and Pierre Chouteau, and Benjamin O’Fallon, four major players in Indian affairs and the interior trade. Clark was Jean Baptiste’s guardian and fur baron Auguste Chouteau his Godfather. O’Fallon, Indian Agent for upper Missouri tribes, had also been under Clark’s guardianship during Jean Baptiste’s years in St. Louis.[5]For O’Fallon, see Dictionary of Missouri Biography, Lawrence O. Christensen, ed. (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1999), 578–80. The group likely promoted the idea of Jean Baptiste going to Europe with the duke.

Duke Paul first met Jean Baptiste on 21 June 1823 at a small settlement half a mile above the mouth of the Kansas River. The community was established by the Chouteaus to trade with Kansas People. Duke Paul recalls the meeting:

Here I also found a youth of sixteen years, whose mother, a member of the tribe of Sho-sho-nes, or Snake Indians, had accompanied the Messrs. Lewis and Clarke, as an interpreter, to the Pacific Ocean in 1804 to 1806. This Indian woman married the French interpreter of the expedition, Toussaint Charbonneau, who later served me in the capacity of interpreter. Baptiste, his son, whom I mentioned above, joined me on my return, followed me to Europe, and has since then been with me.[6]Duke Paul, “First Journey,” 19:303–04.

Duke Paul continued up the Missouri where he hired Jean Baptiste’s father, Toussaint. No doubt Jean Baptiste’s European position was discussed, and likely approved by his father. It was a classic “win-win” benefiting both Jean Baptiste and the duke. The duke had a chance to practice the “Enlightened” method of educating a Native American and gained a resident scholar on North America. As for Jean Baptiste, he would be educated, boarded, and exposed to even more travel and cultures.

It should be noted that whatever bonds the partnership fostered, friendship was not the key motivation. That story comes from an overeager translator who added his own words to the journals of the Duke. The tales of the two spontaneously befriending and becoming “bosom buddies” traveling the world oversimplify and stretch the actual reality. The two certainly enjoyed each other’s company, but due to a lack of written record, we cannot say how much time the two spent together. It is probable that some of Duke Paul’s travels between 1823 and 1829 were without Jean Baptiste.

Crossing the Ocean

La Balize at the Mouth of the Mississippi (1828)

by Paul Wilhelm, Duke of Württemberg

From an early 19th century print titled “Die Balize an der Mündung des Missisippi.” Image is in the public domain.

This painting was created by polyglot Duke Paul during his and Jean Baptiste’s return to the United States in 1828. The alligator may represent the one captured in 1823 while their ship, the Smyrna, waited to enter the Gulf of Mexico.

With the return of Duke Paul from the interior in October 1823, Jean Baptiste’s European adventure began:

On the ninth [of October] the boat reached the Kansas. I remained several hours and picked up the son of Toussaint Charbonneau, who would accompany me to Europe.[7]Duke Paul, “First Journey,” 19:444.

Jean Baptiste apparently inherited his father’s luck with boat travel (see Charbonneau’s Prayer). In transit to New Orleans, the steamboat Cincinnati sank near St. Genevieve. They eventually made their way to New Orleans and boarded the Smyrna. After a long delay at the mouth of the Mississippi, the winter trip across the Atlantic soon became an ordeal.[8]Hans von Sachsen-Altenburg and Robert L. Dyer, Duke Paul of Wuerttemberg on the Missouri Frontier: 1823, 1830, and 1851 (Boonville, Missouri: Pekitanoui Publications, 1998), 79–80. Duke Paul recorded the hardships:

. . . on the 29th . . . we felt the effects of the Bank of Newfoundland which every navigator who crosses this rough region of the sea in the winter months must experience.

From now on the sea fought us with huge waves, and the ship was tossed about so violently that the rolling action became unbearable. The waves struck with such force over board that part of the railing was shattered. Water barrels and other gear were washed into the sea and it was almost impossible to remain on deck. . . .

The thermometer sank to between 5º and zero, hail and snow skiffs filled the air, and in between there was occasional lightning and thunder. The creaking of the masts, the whistling in the storm-torn rigging, the heavy pounding of the waves, the eternal rocking of the boat, and the vast quantities of water that penetrated through the door of the cabin made the situation exceedingly unpleasant.[9]Duke Paul, “First Journey,” 19:462.

Despite it all, the duke, Jean Baptiste, and a live alligator captured below New Orleans, arrived safely in France.

Glimpses of Europe

Jean Baptiste spent most of his European tenure in Württemberg, Germany. There, he continued the “classic education” started in St. Louis and became proficient in German. If Johann (Juan) Alverdo’s experience—another of the duke’s foreign-born protégés at the time—is indicative of Jean Baptiste’s experience, he learned mathematics, geography, and history. He also traveled through Germany, France, England, and perhaps Africa,[10]Susan M. Colby, Sacagawea’s Child: The Life and Times of Jean-Baptiste Charbonneau (Spokane, Washington: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 2005), 107, 110. and he had access to the Black Forest, where he honed his hunting, firearms, and horsemanship skills.[11]Ann W. Hafen, French Fur Traders & Voyageurs in the American West, LeRoy R. Hafen, ed. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, reprint from 1995 edition), 82.

Jean Baptiste also fathered a child while in Europe. Anton Fries was born 20 February 1829 to:

Johann Baptist Charbonneau of St. Louis “called the American” in service of Duke Paul of this place and Anastasia Katharina Fries, unmarried daughter of the late George Fries, a soldier here.

The child lived only three months.[12]Monika Firla, “Johann Alvarado (1815–41), Ein mexikanischer Kammerdiener Herzog Paul Wilhelms von Würtembergish,” Franken 83 (1999); 247–60, cited in Albert Furtwangler, … Continue reading

Mergentheim Castle c. 1800

Photo 2014 by Holger Uwe Schmitt. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Mergentheim Castle was to become the residence of Duke Paul and likely Jean Baptiste at the end of his tenure in Europe. Originally built in the early Middle Ages, the castle had many owners prior to being given to Duke Paul and his new wife, Princess Maria Sophia, in 1827 as their royal residence. Many of the natural science specimens and North American Indian artifacts collected by the duke during his American adventures would be displayed in the castle and are now part of the palace’s museum.[13]“Mergentheim Palace,” Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mergentheim_Palace, accessed 9 June 2023. It is said that Jean Baptiste also had a room here.[14]Sachsen-Altenburg and Dyer, 36.

Paul’s marriage quickly faltered and the couple’s first child was born away from the couple’s home. After concluding a contract of separation with Therese Duchess von Sachsen-Hildburghausen (Princess Maria Sophia of Thurn and Taxis), the duke and Jean Baptiste also left Mergentheim palace. In May 1829, they visited Bordeaux and Madrid before boarding a ship bound for North America.[15]Duke Paul, “First Journey,” 19:472. In 1830, aged twenty-five, Jean Baptiste forever parted ways with Duke Paul.[16]Sachsen-Altenburg and Dyer, 82–4.

Over the next 37 years, Jean Baptiste became a well-known fur trader, hunter, guide, and California miner.

Recommended Reading

- Sacagawea’s Child: The Life and Times of Jean-Baptiste Charbonneau by Susan M. Colby, 2005.

- Duke Paul of Wuerttemberg on the Missouri Frontier: 1823, 1830, and 1851, 1998 by Hans von Sachsen-Altenburg and Robert L. Dyer, 1998.

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Plan a trip related to Jean Baptiste in Europe:

Notes

| ↑1 | Found in literature as Dubourg, Du Bourg and Du Bourge. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Paul Wilhelm, Duke of Württemberg, “First Journey to America in the Years 1822 to 1824,” trans. William G. Bek in South Dakota Historical Collections (State Historical Society, 1938), 19:193, archive.org/details/southdakotahisto0019unse. |

| ↑3 | “Louis William Valentine DuBourg,” Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louis_William_Valentine_DuBourg. |

| ↑4 | For an alternate portrait and biography, see “Duke Paul Wilhelm of Württemberg,” Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Duke_Paul_Wilhelm_of_W%C3%BCrttemberg.. |

| ↑5 | For O’Fallon, see Dictionary of Missouri Biography, Lawrence O. Christensen, ed. (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1999), 578–80. |

| ↑6 | Duke Paul, “First Journey,” 19:303–04. |

| ↑7 | Duke Paul, “First Journey,” 19:444. |

| ↑8 | Hans von Sachsen-Altenburg and Robert L. Dyer, Duke Paul of Wuerttemberg on the Missouri Frontier: 1823, 1830, and 1851 (Boonville, Missouri: Pekitanoui Publications, 1998), 79–80. |

| ↑9 | Duke Paul, “First Journey,” 19:462. |

| ↑10 | Susan M. Colby, Sacagawea’s Child: The Life and Times of Jean-Baptiste Charbonneau (Spokane, Washington: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 2005), 107, 110. |

| ↑11 | Ann W. Hafen, French Fur Traders & Voyageurs in the American West, LeRoy R. Hafen, ed. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, reprint from 1995 edition), 82. |

| ↑12 | Monika Firla, “Johann Alvarado (1815–41), Ein mexikanischer Kammerdiener Herzog Paul Wilhelms von Würtembergish,” Franken 83 (1999); 247–60, cited in Albert Furtwangler, “Postscript: Sacagawea’s Son: New Evidence from Germany,” Oregon Historical Quarterly, 102, no. 4 (Winter, 2001): 518-523, www.jstor.org/stable/20615188. |

| ↑13 | “Mergentheim Palace,” Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mergentheim_Palace, accessed 9 June 2023. |

| ↑14 | Sachsen-Altenburg and Dyer, 36. |

| ↑15 | Duke Paul, “First Journey,” 19:472. |

| ↑16 | Sachsen-Altenburg and Dyer, 82–4. |