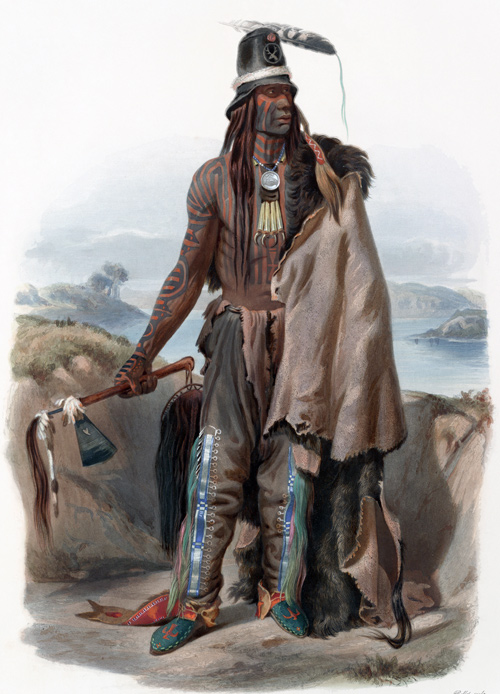

Prior to departing from winter camp at Wood River, the Hidatsa were relatively well-understood by Lewis and Clark, but not known by that name. One of their St. Louis informants, Jean Baptiste Truteau, called them by their French name Gros Ventre which literally translates as Big Belly. They didn’t have bigger bellies than any other Native Americans, but that meaning was translated by French traders from a Plains Sign Language gesture for the tribe where the hand moves in the shape of an extended stomach.[1]Frank Henderson Stewart, Handbook of North American Indians: Plains Vol. 13, Raymond J. DeMallie, Ed. (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institute, 2001), 346.

History

According to Crow and Hidatsa tradition, the two peoples split from a single group. Both are Siouan, and evidence supports their common past. Clark was told of split and wrote:

he [Sheheke] Said that the Menitarras [Hidatsa] Came out of the water to the East and Came to this Country and built a village near the mandans from whome they got Corn beens &c. they were very noumerous and resided in one village a little above this place on the opposit Side. they quarreled about a buffalow, and two bands left the village and went into the plains, (those two bands are now known bye the title Pounch, and Crow Indians.

—William Clark, 18 August 1806

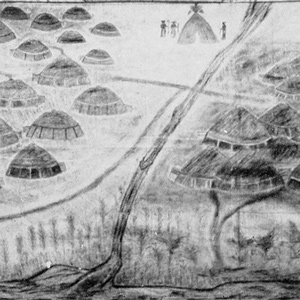

In 1781, the Hidatsa population was reduced to about 2000 after a smallpox epidemic. At this same time, plains village tradition tribes became more vulnerable to nomadic tribes such as the Sioux. The Hidatsa settled in three villages just north of two Mandan villages in a complex now called the Knife River Villages. There, they practiced horticulture and hunting in the manner of the Plains Village tradition. They appeared to be more war-like than their Mandan allies and were likely the people who traveled to the Three Forks of the Missouri where they encountered the Lemhi Shoshones and eventually captured Sacagawea, a valued member of the expedition.

Hidatsa Village Traders

The Hidatsa story of Sakakawea differs significantly than that of the Lemhi Shoshone and academic historians. The spelling Sakakawea reflects a Hidatsa meaning and birthname. The spelling Sacajawea reflects the Lemhi Shoshone meaning and interpretation of her life and Sacagawea the spelling and story commonly accepted by academic historians.[2]Sacagawea’s name and life story is often debated. Being a popular argument, the controversy is outlined at Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacagawea#Spelling_of_name. For the Hidatsa … Continue reading

What we do know about Sacagawea is that she and her husband—independent trader Toussaint Charbonneau—were living among the Awatixa division of the Hidatsa at Metaharta Village. For decades prior to the expedition, fur traders had commerce with the Hidatsa and when Lewis and Clark arrived, the Knife River Villages were teeming with traders from the Hudson’s Bay and North West companies. Two traders from the latter company, François-Antoine Larocque and Charles McKenzie, left a significant written record of their interactions with the expedition during the 1804–05 winter at Fort Mandan.[3]The writings of Larocque and McKenzie provide alternate perspectives on the expedition’s winter stay at Fort Mandan. Where appropriate, excerpts are included in this website’s Day by Day … Continue reading

A Lasting Peace?

In their role as United States diplomatic envoys, the captains prompted a peace between the Arikaras, Hidatsas, and Mandans. That was only temporary, as the death of Too Né (Eagle Feather) on his Washington City trip, would turn his people against the United States and their Mandan-Hidatsa allies. Just a year after the expedition, the Arikara hampered efforts to return Mandan Sheheke’s diplomatic envoy to his home village. Sheheke eventually returned, but some Hidatsa would kill him in 1812.

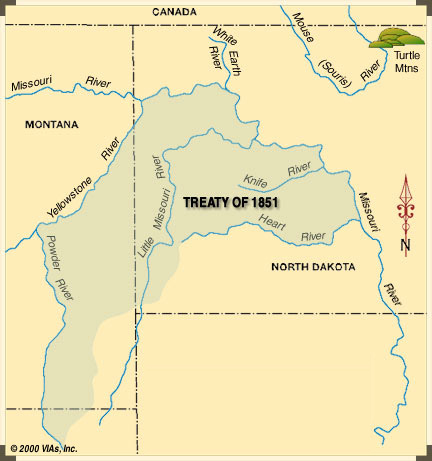

In the next decade, weakened by skirmishes with traders and the U.S. Army, the Arikara would seek sanctuary with the Hidatsas and Mandans. Ironically, the peace between the three tribes sought by the captains, had finally come to pass. With the establishment of the Fort Berthold Reservation in 1870, the Knife River villages no longer belonged to the Three Affiliated Tribes.[4]Baker, 329–331, 346-47; William Bright, A Glossary of Native American Toponyms and Ethnonyms from the Lewis and Clark Journals, University of Colorado, accessed on 28 April 2020, … Continue reading

Synonymy

The synonymy of the Hidatsa people is rich, complex, and often confusing. The simplified form below is meant to help the reader better understand and search the literature.[5]For more academic synonymies see (Douglas R. Parks, Handbook of North American Indians: Plains, 344 and Frederick Webb Hodge, Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico, Vol. 1 (Washington: … Continue reading

Both the Astinas and Hidatsas are called Big Bellies, Gros Ventre and Minnetares. To avoid confusion, 19th-century writes adopted the terms “Gros Ventres of the Prairie” (Atsina) and “Gros Ventres of the Missouri” (Hidatsa). In the context of this synonymy, all the terms below refer to the Hidatsas.

Alternate spellings by the expedition journalists are enclosed in [brackets].

- Names for the Hidatsa

- Minitaree [Muneturs, Minitaries, Minetares, Me-ne-tar-e, Menitarras]

- Gros Ventre [Grovanter, Gross Vaunter, Grosvantres, Grovantrs, Grosvauinties, Grousevauntaus]

- Big Bellies [Big Belleys]

- Watersoon [Water Soix, Water Souix, Weta Soaux, We ter Soon]

- Three Divisions and Villages

- At the time of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, there were three divisions each roughly associated with their own villages:

- Awaxawi of Mahawha Village

- [Arwerharmays, Ah-wâh-hâ-way]

- The Awaxawi were also known as Shoe or Mocassin or in French, Soulier, les souliers, and Gens des Soulier [Shoes Men].

- Mahawha is also known as the Amahami site [Arwarharmay, Arwerhrmay, Mahaha, Mahawha, Mar-har-ha, Mah-har-ha, Little Menetarre Village].

- The journalists also called this the Lower Village and sometimes enumerated it simply as number 3, or third village.

- Awatixa of Metaharta Village

- This village also included some Hidatsa proper and is also known as the Sakakawea site and Little or Petite village. The journalists sometimes called it Middle Village and enumerated it as number 4.

- Hidatsa proper of Menetarra Village

- This village, the northernmost, was also called Big Hidatsa, Grand Village, Upper Village, and sometimes enumerated as number 5.

Selected Pages and Encounters

Assessing the Legacy of Lewis and Clark

by Clay S. Jenkinson

The author proposes a few metaphors for the Lewis and Clark story, not in any definitive way, but merely to help us all think about the legacy of the expedition.

Meet the Three Affiliated Tribes

Interviews with tribal members

My name is Tex Hall. I’m the tribal chairman of the Three Affiliated Tribes . . . the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation . . . here at Fort Berthold at present day New Town, North Dakota. I would like to speak a little Hidatsa because I am Mandan and Hidatsa.

Hidatsa Territory

Becoming the Fort Berthold Reservation

After leaving Fort Mandan on 7 April 1805, the expedition traveled for several days through Hidatsa territory. Much of that area would become the Fort Berthold Reservation of the Three Affiliated Tribes, a coalition of Hidatsa, Mandan, and Arikara.

The Hidatsa Story of Sakakawea

Alternate spelling, alternate story

This story of Sakakawea (Sacagawea) as told by Bulls Eye to Major Welch circa 1924 provides an alternate version of her life before the expedition. To begin, he says that she was Hidatsa, not Shoshone….

Flag Presentations

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Lewis and Clark usually distributed flags at councils with the chiefs and headmen of the tribes they encountered—one flag for each tribe or independent band.

January 1, 1804

A new year at Wood River

At Wood River, Clark stages a shooting contest between local farmers and the enlisted men. He reports on two drunk soldiers and meets with a new washer woman. Both captains begin their weather diaries.

October 27, 1804

Ruptáre

At the second Mandan village—Ruptáre—they hire free trader René Jusseaume as an interpreter. They camp opposite Mahawaha, the Awaxawi Hidatsa village at the mouth of the Knife River.

The Knife River Villages

Marketplace

by Joseph A. Mussulman

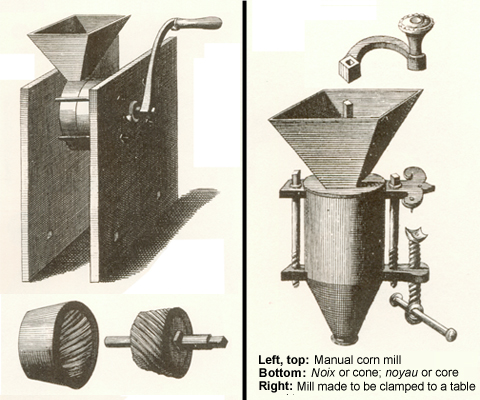

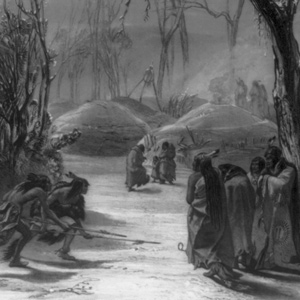

Reaching the mouth of the Knife River on 27 October 1804, the expedition arrived in the midst of a major agricultural center and marketplace for a huge mid-continental region. The five permanent earth lodge communities there offered a panorama of contemporary Indian life.

October 29, 1804

Mandan and Hidatsa council

Opposite the Knife River, Mandan and Hidatsa chiefs come from each village to council with the captains. A long speech is given, and the captains ask them to smoke the pipe of peace with an Arikara chief.

October 31, 1804

Black Cat speaks

Clark visits Posecopsahe (Black Cat), the main chief at Ruptáre, one of the five Knife River Villages. Posecopsahe wishes for peace and returns two beaver traps recently stolen from two French traders.

November 5, 1804

Raising the huts

The day is spent raising Fort Mandan cabins and splitting boards for the cabin lofts. Mandan hunters report capturing 100 pronghorns, Clark’s rheumatism continues, and Lewis spends the day writing.

November 16, 1804

Moving into the huts

At Fort Mandan, the morning brings thick frost. Fortunately, the enlisted men can move from their tents into unfinished cabins. The captains learn of a dispute between Assiniboines and their Hidatsa hosts.

November 25, 1804

Hidatsa mix-up

Lewis, interpreters Jusseaume and Charbonneau, and five men embark on a diplomatic mission to a Hidatsa village. Two Hidatsa chiefs—Black Moccasin and Rd Shield—come to Fort Mandan with similar intentions.

November 27, 1804

Mandan deceptions

Lewis returns to Fort Mandan with two Hidatsa chiefs, and the captains learn that the Mandans have been telling lies to the Hidatsas. Seven Canada-based traders arrive at the Knife River Villages.

November 30, 1804

A military reprisal

Responding to news of a deadly Sioux and Arikara attack on Mandan hunters about 25 miles from Fort Mandan, Clark leads a military force to Mitutanka to gather warriors and pursue the attackers.

December 7, 1804

Hunting buffalo

A group of hunters joins with the Mandans, and Sgt. Gass is impressed with their buffalo hunting skills and well-trained horses. By day’s end, several suffer frostbite, and Clark issues half a gill of rum.

December 26, 1804

The good old game

A North West Company trader comes to Fort Mandan to hire Charbonneau as a translator. Clark learns that a Hidatsa attempt to retrieve stolen horses was somewhat successful, and Lewis plays backgammon.

January 1, 1805

A new year at Fort Mandan

At Fort Mandan, New Year’s Day starts with rain and cannon fire. Several enlisted men are allowed to visit a nearby Mandan village, and Clark orders York to dance for them. The day ends snowy and cold.

January 15, 1805

Lunar eclipse

At Fort Mandan, celestial observations are made during a lunar eclipse. The captains receive their first Hidatsa visitors since November, and Pvt. Whitehouse is brought in to recover from frozen feet.

January 16, 1805

Hidatsa-Mandan jealousy

At Fort Mandan, the captains attempt to smooth over Hidatsa and Mandan jealousy. Lewis demonstrates the air gun and cannon, and the captains caution Seeing Snake not to war with the Shoshones.

February 1, 1805

Pacifying Fears the Snake

Hidatsa chief Fears the Snake brings corn to Fort Mandan as payment for a war axe, and the captains try to talk him out of fighting the Sioux and Arikaras. The day is cold and the hunting poor.

February 22, 1805

Fort Mandan rain

The residents of Fort Mandan receive their first rain since last November. Lewis and his recently returned hunters rest while the other enlisted men work to free the boats from the river’s snow and ice.

February 28, 1805

Arikara and Sioux news

Traders arrive at the Knife River Villages with news and two plant specimens for Lewis. About six miles from Fort Mandan, several enlisted men cut down cottonwood trees to make dugout canoes.

March 6, 1805

Shannon's accident

At the canoe camp away from Fort Mandan, Pvt. Shannon cuts his foot with an adze. Surrounding the Knife River Villages, some Hidatsas burn off dead winter grass making the air smoky.

March 9, 1805

Grand Chief Le Borgne

Le Borgne pays his first visit to Fort Mandan where the captains try to impress this important Hidatsa chief. Despite Lewis’s efforts, he leaves with disdain for all except the blacksmith and gunsmith.

March 10, 1805

Hidatsa migration

Black Moccasin and another Hidatsa—likely White Buffalo Robe Unfolded visit Fort Mandan. They tell the captains how the Mandans and Hidatsas were decimated by wars and smallpox and then banded together.

March 19, 1805

Hidatsa war parties

At Fort Mandan, two Mandan chiefs tell the captains that the Hidatsas are forming war parties. Sgt. Gass seeks helpers to move the new dugout canoes from his canoe camp to the river.

March 22, 1805

Man Wolf Chief visits

At Fort Mandan, Man Wolf Chief of Menetarra is given the standard diplomatic treatment: an Indian peace medal, gifts, and a speech. Engagé François Rivet comes for his canoe.

March 23, 1805

A Hidatsa vocabulary

Fur trade clerks Charles McKenzie and François-Antoine Larocque end their visit at Fort Mandan in present North Dakota. A Hidatsa man helps the captains record a vocabulary of his language.

April 5, 1805

Loading the small boats

The men load the red and white pirogues and six new dugout canoes. Sgt. Patrick Gass recalls the Indian sexual practices experienced during his stay at Fort Mandan amongst the Knife River Villages.

April 12, 1805

Little Missouri River

Early in the day, a crumbling bank threatens the red pirogue. They spend most of the day at the Little Missouri River and see beaver, empty Assiniboine camps, creeping juniper, and wild onions.

August 19, 1805

Clark crosses Lemhi Pass

Clark and several Shoshones cross Lemhi Pass and camp on Pattee Creek. At Fortunate Camp, Lewis starts a multi-day treatise describing the Lemhi Shoshones, and Charbonneau must pay for Sacagawea.

August 11, 1806

Cruzatte shoots Lewis

Lewis is shot through the buttock. An Indian attack is suspected, but likely Pvt. Cruzatte mistook him for an elk. Clark meets fur traders who share news of the barge, the fur trade, and Indian wars.

August 13, 1806

All hands aboard

With all hands aboard, they start the day as one corps for the first time since separating on 3 July 1806. With favorable winds, they make eighty-six miles and pass the Little Missouri River.

August 14, 1806

Among old friends

The expedition arrives at the Knife River Villages—one of which is the home of the Charbonneau family. The captains meet with various chiefs, and Clark invites them to travel to Washington City.

August 15, 1806

Broken promises of peace

At the Knife River Villages in present North Dakota, the captains hear of several broken promises of peace among the tribes with whom they had established peace agreements on the outward journey.

August 18, 1806

A Mandan history lesson

Despite windy conditions, the expedition makes forty miles down the Missouri River. Chief Sheheke (Big White) tells Clark his people’s history. Near the Heart River, he tells the Mandan Creation Story.

Notes

| ↑1 | Frank Henderson Stewart, Handbook of North American Indians: Plains Vol. 13, Raymond J. DeMallie, Ed. (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institute, 2001), 346. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Sacagawea’s name and life story is often debated. Being a popular argument, the controversy is outlined at Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacagawea#Spelling_of_name. For the Hidatsa version, see also Gerard A. Baker in Lewis and Clark through Indian Eyes, Alvin M. Josephy, Jr., Ed. (New York: Vintage Books, 2006), 123–136. |

| ↑3 | The writings of Larocque and McKenzie provide alternate perspectives on the expedition’s winter stay at Fort Mandan. Where appropriate, excerpts are included in this website’s Day by Day pages. See also W. Raymond Wood and Thomas D. Thiessen, Early Fur Trade on the Northern Plains: Canadian Traders among the Mandan and Hidatsa Indians, 1738–1818 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1985), in passim. See also Larocque at Fort Mandan. |

| ↑4 | Baker, 329–331, 346-47; William Bright, A Glossary of Native American Toponyms and Ethnonyms from the Lewis and Clark Journals, University of Colorado, accessed on 28 April 2020, https://lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu/item/lc.sup.bright.01; Moulton, Journals, 3:206n8. |

| ↑5 | For more academic synonymies see (Douglas R. Parks, Handbook of North American Indians: Plains, 344 and Frederick Webb Hodge, Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico, Vol. 1 (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology, Government Printing Office, 1912), 47, 547–549. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.