A Blackfoot Indian on Horse-back

Karl Bodmer (1809–1893)

Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library.[2]“Blackfoot Indianer zu Pferd. Indien Pieds Noir à cheval. A Blackfoot Indian on horse-back.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed 14 December 2020. … Continue reading

Next to grizzly bears and Mother Nature, the most feared enemy of American fur trappers traveling along the upper Missouri River were the Niitsítapi or Blackfeet, the “Original People” or “Prairie People.”[3]The term Blackfeet referred to northwestern plains nations who sometimes wore black moccasins dyed with paint or darkened with ashes. J. Cecil Alter, James Bridger (Columbus, OH: Long’s College … Continue reading The Blackfeet Confederacy comprised the dominant military power on the northwestern plains. Blackfeet sought to maintain their hegemony by preventing American traders and trappers from trading with and strengthening the Shoshone, Crow, Flathead [Salish], and Nez Perce. They accomplished this by harassing and attacking American trappers and stealing their horses and furs. Blackfeet enmity toward the Americans and their determination to keep them out of their neighborhood instilled apprehension and fear in the heart of virtually every traveler venturing along the Yellowstone and Missouri rivers before 1840.

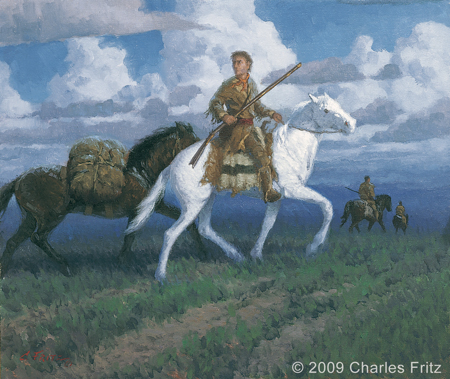

Lewis’s “Accedental Interview”

Fleeing the Blackfoot Revenge

16″ x 19″ oil on canvas

© 2009 by Charles Fritz. Used by permission.

The first documented encounter between Americans and Blackfeet occurred on 26 July 1806, when four members of the Corps of Discovery—Lewis, Drouillard, and the Field brothers—met and encamped with eight Piegan or Atsina teenage boys along the south side of the Two Medicine River.[4]Helen B. West, Meriwether Lewis in Blackfeet Country, Bureau of Indian Affairs, Blackfeet Agency (Browning, MT: Museum of the Plains Indian, 1964). [See also on this site Fight on the Two Medicine … Continue reading Lewis, through George Drouillard, explained to the Blackfeet boys that America wanted to make peace and establish trade with the Indians of the Plains and Rockies. The Blackfeet, who kept other tribes from coming north to trade with North West Company traders and at Hudson’s Bay Company posts along the Saskatchewan River, realized their trading advantage would diminish if the “Big Knives” (Euro-Americans) provided their enemies with weapons and supplies. Blackfeet had no need to ally themselves with Americans because they already received armaments and supplies at British posts along the Saskatchewan River.[5]Horse stealing represented the central focus of Plains Indian culture. Alexander Henry regarded the Blackfeet tribes as the “most independent and happy people of all the tribes East of the … Continue reading

After spending a pleasant Saturday evening together, Lewis posted a guard to watch their horses and weapons. On Sunday morning Lewis awoke when he heard Drouillard shout, “damn you let go my gun.” The young Indians had seized an opportunity to steal their guns and horses since raiding represented the fastest way to acquire wealth and status within the tribe and their party outnumbered the Americans two to one. Reubin Field seized his gun, wrestled it away, and mortally stabbed Calf-Standing-on-a-Side-Hill [Side Hill Calf] with his knife. Shortly thereafter, Lewis pursued those taking the horses and shot He-Who-Looks-at-the-Calf in the belly. The young man returned Lewis’s fire, his bullet narrowly missing Lewis who wrote that he felt the wind of the bullet pass near his head. Lewis left a peace medal around the neck of Calf-Standing-on-a-Side-Hill that the Blackfeet “might be informed who we were.” After recapturing four horses, the Americans rode for 18 hours straight, fearing Blackfeet reprisal. Fortuitously, on Monday morning 28 July 1806, Lewis’s entourage met the party who had dug up the caches at the Great Falls and together they descended the Missouri River to rejoin Clark’s party near the confluence of the Yellowstone and the Missouri.[6]Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition, 13 vols. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983-2001), 8:127-37, esp. 134-35; John C. Jackson, “The Fight on Two … Continue reading

Historians have asserted that the enmity between the Niitsítapi (Blackfeet) and the Nistosuniquen—an Algonquian word for “Big Knives,” referring to long Green River knives (or perhaps even swords) mountain men carried—could be traced to this initial violent encounter in 1806. For example, in 1807 British trader David Thompson noted, “the murder of two Peeagan Indians by Captain Lewis of the U.S. drew the Peeagans to the Missouri.”[7]David Thompson, David Thompson’s Narrative of His Explorations in Western America, 1784-1812 (Toronto: Champlain Society, 1916), 375. See also Ted Binnema, “Allegiances and Interests: … Continue reading Even if Lewis’s group had not killed the Blackfeet teenagers, several additional factors help explain the hostile relations between Blackfeet and Americans during the first four decades of the nineteenth century: namely, the geographic location of the Blackfeet Confederacy; the confederation’s alliance with the British; the inclusion of the Atsinas within the confederation; and, materialistic competition resulting from the fur trade.

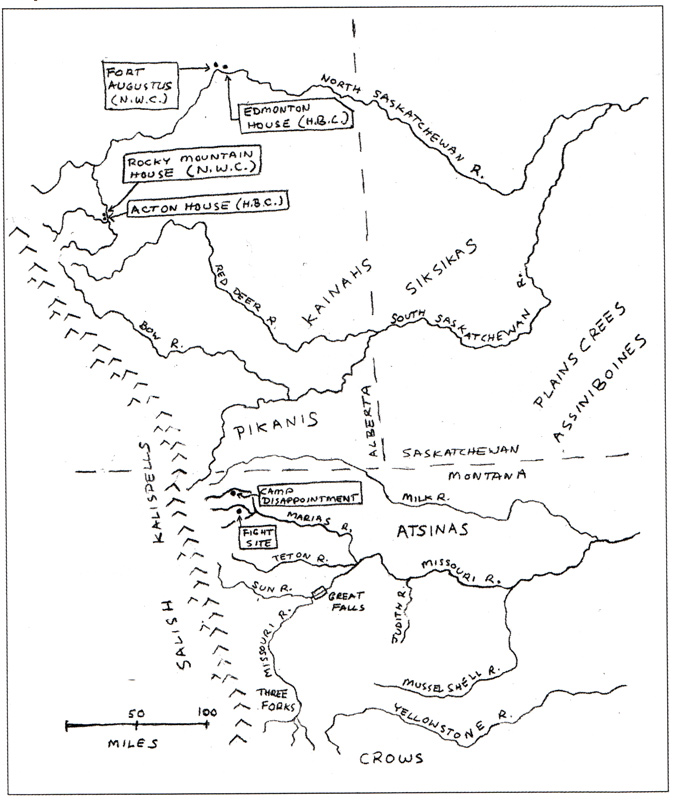

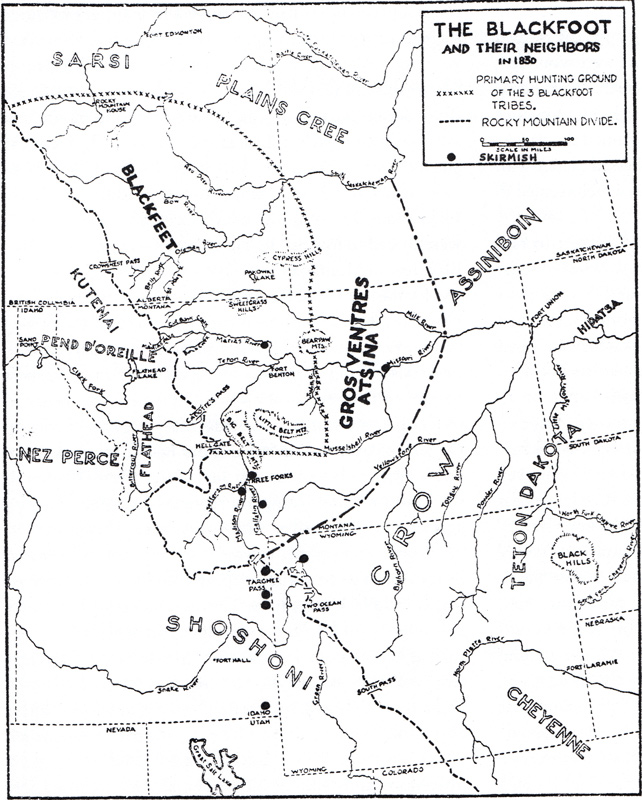

The Blackfeet Confederacy

The First Nations comprising the Blackfeet Confederacy included the plains Algonquian-speaking Siksikas/Siksikáwa (Blackfoot Proper), Kainahs/Káínaa (Bloods), and Piegan (Aapátohsipikáni or Northern Piegan in Canada; Aamsskáápipikani or Southern Piegan/Blackfeet in Montana). Two other nations also belonged to the alliance: north of the forty ninth parallel, the Tsuu T’ina (Sarcee); south of the border, the Atsinas (Gros Ventres of the River [Prairie]), relatives of the Arapahos. Hereafter, the term Blackfeet applies to Indians in any one of these nations when no distinction otherwise is made, although most incidents in Montana and the Intermountain West usually involved either the Southern Piegans or the Atsinas, two nations whom American trappers took the liberty to lump together under the all-encompassing term “Blackfeet.”[8]The tribal designation in Canada is always Blackfoot while many American fur trade references use the term Blackfeet, which I have done to avoid going back and forth. Donald Ward, “Blackfoot … Continue reading

The Blackfeet Confederacy straddled the demarcation line between the rapidly expanding American and British territories. With the majority of their tribal lands in Canada, North West Company and Hudson’s Bay Company traders established the first contact with the Blackfeet, and developed an extensive trade with them at British posts on the Saskatchewan River. Blackfeet monopolized the fur trade of the northwestern plains by preventing other native nations from trading at British posts. This allowed Americans an opportunity to establish alliances with a majority of nations south of the forty-ninth parallel, such as the Crow People, Shoshone, Nez Perce, and Flathead (Salish). These tribes welcomed opportunities to trade and acquire weaponry and commodities to repel the Blackfeet. Blackfeet saw potential danger as their traditional enemies to the west and south grew stronger and became more formidable opponents when backed by American weapons.[9]John Jacob Astor’s men traded firearms to Flathead Indians in 1810. Heretofore, these tribes had been forced by the Blackfeet to travel all the way to the Missouri and trade with the Hidatsas … Continue reading

The British seized upon this situation and stirred up the growing animosity between Blackfeet and Americans. Dependency on British guns and whiskey ensured Blackfeet assistance in helping the British attempt to expel the Americans from the Pacific Northwest. The Blackfeet acquired guns from North West Company traders, the Hudson’s Bay Company, and Cree and Assiniboine neighbors. The well-armed Blackfeet gained immediate advantage over their southern rivals and began their domination of the Northern Plains. Horses stolen from Flatheads, Nez Perces, and Shoshones mobilized their firepower. The Blackfeet tenaciously and ferociously drove all the weaker nations to the south and west over the Rocky Mountains.[10]John C. Ewers, The Blackfeet: Raiders on the Northwestern Plains (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1958), 21-22.

Oral Histories

Wolf Calf: Alleged Witness

Photo by George Bird Grinnell, (1895), for Olin D. Wheeler, The Trail of Lewis and Clark. See also Wheeler’s “Trail of Lewis and Clark”.

Wolf Calf, a Blackfoot interviewed by George Bird Grinnell in 1895, claimed to have taken part in the Two Medicine Fight as a boy of 13.

Several versions of Blackfeet oral history describe the encounter differently. One account relates that the boys crept into Lewis’s camp to steal from an enemy, a coming-of-age ritual demonstrating courage. In another version, “Lewis and his party ran into a group of young boys from the Skunk Band who were herding horses back to camp from a previous foray.” The boys camped with and wagered with Lewis. “There is a story of a race. In the morning, they went to part company and the Indians took what they had won. That was it. That’s when they were killed.” An important Blackfeet account comes from George Bird Grinnell’s 1895 interview with Wolf Calf, a 102-year-old Blackfeet who said that he was personally at the fight scene when he was thirteen. He said their raid leader “directed the young men to try to steal some of their things. They did so early the next morning, and the white men killed the first Indian [Side Hill Calf] with their big knives.” Wolf Calf acknowledged that the boys were frightened but that they “were bitterly hostile to the whites after the incident and ashamed because they had not killed all the white men.” Most importantly, when Lewis left the peace medal around the dead Indian’s neck, it would have seemed like he was “counting coup” and it would have appeared “as a form of scalping.” As a result, Blackfeet closed their borders to Americans, “attacking and killing any intruder they could find within their borders.”[11]Many years after the encounter, Wolf Calf claimed to have been a member of this Piegan raiding party and offered his account of the incident. Olin D. Wheeler, The Trail of Lewis and Clark, … Continue reading

Upon the expedition’s return to St. Louis in September 1806, its members related tales about the upper Missouri country teeming with beaver. Preparations to capitalize on this knowledge, especially in St. Louis, reached a fevered pitch. Several Spanish and French traders sought to be the first to take advantage of this untapped source of wealth. Perhaps the most important trader to take action was Manuel Lisa. Lisa quickly organized a large party of men to ascend the river, which included about a third of the veterans of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Within the next several years Blackfeet killed at least two former Corps of Discovery members.[12]Manuel Lisa already had learned about the wealthy tribes of the West, the Arapahos on the Platte, the Crows of the Yellowstone, and the Blackfeet of the upper Missouri. Richard E. Oglesby, Manuel … Continue reading

Potts’ Death, Colter’s Escapes

Unlike the British, who built trading posts outside of Blackfeet territory and encouraged the Indians to do the trapping, Americans constructed forts within Blackfeet territory starting in 1807 and began trapping beaver on their own. Americans built posts along the Yellowstone, the Missouri’s Three Forks, and Henry’s Fork of the Snake River. These encroachments infuriated the Blackfeet. They felt their resources were being robbed, which led to hostile confrontations as they repeatedly drove Americans from their land. These circumstances set the stage for the bloody encounters during the first half of the nineteenth century.[13]Alexander Henry recorded on 14 September 1808, at Rocky Mountain House in Canada that “Last year, it is true, we got some beaver from them; but this was the spoils of war, they having fallen … Continue reading

Lisa’s Missouri Fur Company group ascended the Yellowstone to its confluence with the Bighorn and in the fall of 1807 erected Fort Raymond, the first American post near Blackfeet territory. In November, Lisa sent John Colter to find and bring in the Crows, Blackfeet, and other tribes to trade. While traveling with a group of several hundred Flatheads along the Gallatin River, fifteen hundred Blackfeet attacked Colter and his Flathead allies. With the help of some Crow reinforcements who joined in the fray, they repelled the Blackfeet attack.[14]Thomas James, Three Years among the Indians and Mexicans, ed. by Walter B. Douglas (St. Louis: Missouri Historical Society, 1916), 52-53.

This encounter further inflamed Blackfeet hostility toward Americans. The next year, John Colter and John Potts paddled up the Jefferson River, the most western of the Missouri River’s three forks, stopping occasionally to trap the plentiful beaver. As they paddled their canoe upstream, several hundred Blackfeet surrounded them and ordered them to shore. Colter went to the shore where they stripped him naked; Potts decided he would rather stay in his canoe. Struck by a well-aimed arrow as he shot the Indian who fired upon him, Potts’s body was immediately riddled with dozens of bullets. “They dragged the body up onto the bank, and with their hatchets and knives cut and hacked it all to pieces, and limb from limb.” They threw Potts’s body parts at Colter’s face. Colter narrowly escaped death by running a race for his life. In the following months, Colter returned to the Jefferson River to retrieve his traps that he had dropped in the river before the Blackfeet had attacked Potts and him. While camping one night on the Gallatin River, Colter heard the clicking of gun hammers and quickly dove into the thicket, narrowly escaping death for a third time. Colter made the long journey back to Fort Raymond, decided his luck with Blackfeet had run out, and promised his Maker to leave the country and “be d—d if I ever come into it again.” Colter floated down the Missouri and never returned.[15]Colter’s famous race for life is masterfully chronicled by Thomas James as he heard the story from Colter while they trapped beaver together on the Three Forks. James, Three Years among the … Continue reading

Drouillard’s Demise

These three run-ins with Colter angered the Blackfeet to the point that they determined to drive all Americans out of the area. Simultaneously, Manuel Lisa continued seeking Blackfeet contact. He sent men, under the command of Andrew Henry, Reuben Lewis, and Pierre Menard, to the Three Forks to establish a trading post.[16]The Crows, with new American muzzle-loaders, defeated a party of Atsinas on the Yellowstone River. This was an unprecedented event that resulted in constant retaliation by the Atsinas in an attempt … Continue reading Blackfeet warriors killed two dozen of Menard’s American trappers in the spring of 1810 near the Three Forks of the Missouri. The remaining trappers cowered in their makeshift fort, afraid to leave for fear of a Blackfeet reprisal. Former expedition member George Drouillard ventured out alone twice and brought back nearly twenty beaver pelts. As a French Canadian Shawnee, Drouillard boasted he was too much Indian himself to be captured or killed. On the third day, he convinced two Lenape Delawares to leave the fort with him—all three failed to return. A search party found the Delawares’ bodies “pierced with lances, arrows, and bullets and lying near each other.” Nearby they discovered what remained of Drouillard and his horse. Drouillard had put up a fight, “being a brave man and well armed with rifle, pistol, knife, and tomahawk.” The pools of blood documented where Blackfeet had been wounded. The famous scout and hunter’s body was “mangled in a horrible manner; his head cut off, his entrails torn out, and his body hacked to pieces.”[17]James, Three Years among the Indians and Mexicans, 82-83; and M.O. Skarsten, George Drouillard: Hunter and Interpreter for Lewis and Clark and Fur Trader, 1807-1810 (Glendale, CA: Arthur H. Clark … Continue reading

Atsina Attacks

The Blackfeet hated the Americans’ invasion, especially the construction of American forts within their lands. Nestled between the Jefferson and Madison rivers, the trapper-traders experienced great success for the first few weeks. They realized that if they could stay the whole season they would be financially secure for years. The Atsinas had other plans. Trappers could not venture out a single mile without Atsinas attacking them. “So constant were the Indian attacks that little trapping could be done.”[18]Ewers, Blackfeet, 50. These attacks demoralized the trappers, causing Menard to lead a group of them back to St. Louis. Henry, convinced of the futility of staying there, took the remaining men and crossed the Continental Divide to build a fort on Henry’s Fork of the Snake. After a terrible winter of suffering and hardship, Henry’s party returned to St. Louis. Several hundred Blackfeet warriors gave them a violent sendoff near the Three Forks, killing one trapper but suffering two dozen casualties themselves.[19]Oglesby, Manuel Lisa and the Opening of the Missouri Fur Trade, 115. Henry and his men believed the British incited Blackfeet hostility toward them. Meriwether Lewis received a letter from his brother Reuben, who was part of the group, wherein Reuben confided, “I am confident that the Blackfeet are urged on by the British traders in their country.”[20]Reuben Lewis to Meriwether Lewis, April 21, 1810, Meriwether Lewis Collection, Missouri Historical Society Archives, St. Louis, Missouri.

Astorian Alterations

American wariness and fear of Blackfeet increased in 1811 when the overland Astorians—John Jacob Astor’s American Fur Company who were traveling to the mouth of the Columbia under the leadership of Wilson Price Hunt—altered their course and traveled overland through present-day Wyoming rather than risk venturing where the Piegans and Atsinas lived. The following year Robert Stuart, on his return trip from Astoria to St. Louis, carefully traveled “out of the walks of the Blackfoot Indians, who are very numerous and inimical to whites.”[21]Kenneth A. Spaulding, ed., On the Oregon Trail: Robert Stuart’s Journey of Discovery, 1812-1813 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1953), 94.

The Prairie People won round one of Blackfeet-American hostilities. Piegan and Atsina warriors successfully drove the Big Knives out of the upper Missouri River and burned down all three American trading posts. The Blackfeet resumed fighting their Indian enemies who recently had defeated them several times with the help of American weapons. Blackfeet successfully expelled all the Americans who had gone to trap in the Three Forks country, stealing their beaver pelts, horses, traps, guns, and ammunition in the process. The War of 1812 further disrupted and halted American trapping and trading on the upper Missouri. The following years marked relative peace among Blackfeet and Americans for one simple reason: they experienced very little contact. The British drove the Astorians from the Pacific Northwest; the North West Company forced John Jacob Astor to sell his trading post, Fort Astoria, to them for a fraction of its value; and, the Blackfeet already had driven Lisa, Henry, and Menard’s trappers from their territory and destroyed their forts.

A Medicine Line is Drawn

The War of 1812 had a major impact on most native nations. The competition between Americans and British for control of the fur trade in the upper Mississippi and upper Missouri areas forced Indians to choose sides. Most Indians in the Great Lakes and upper Mississippi region tended to favor the British, while those living along the lower Missouri affiliated themselves with America. Early British successes in the war helped them recruit Indian allies. American frontier towns feared neighboring tribes would switch alliances when they learned of American defeats. By 1814, the British and Americans agreed to return to prewar status by signing the Treaty of Ghent. However, hostility among the natives took years to dissipate. When the British and Americans entered into another treaty in 1818, the two nations resolved their long-standing boundary issue by extending the forty-ninth parallel west to the Rocky Mountains. This artificial boundary line bisected the territory inhabited by the nations comprising the Blackfeet Confederacy. Nevertheless, by 1819, the fur trade on the upper Missouri River looked like a promising venture to entrepreneurs in St. Louis.[22]Kate L. Gregg, “The War of 1812 on the Missouri Frontier,” Missouri Historical Review (Part 1, October 1938; Part 2, January 1939; part 3, April 1939), 3, 16, 327. Gregg’s three … Continue reading

The 1818 treaty between America and Great Britain had declared joint-occupation of the Oregon Country. America was caught up in expansionism. In 1819, the U.S. government demonstrated its support for the fur trade by allocating funds for the Yellowstone Expedition. Unfortunately, this expedition met with disaster as the steamboat became marooned on a sandbar in the Missouri River. Upon returning, Major Thomas Biddle addressed the U.S. Senate on 29 October 1819. He initiated discussions on the government’s fur trade involvement. In 1821, the government relinquished its control over the fur trade.Senate Executive Document, U.S. Senate, 16th Congress, 1st Session (Washington, D.C., 1820).

Immell-Jones Massacre

After Manuel Lisa’s death in 1820, new entrepreneurs appeared. Joshua Pilcher’s newly reorganized Missouri Fur Company was one of the first to try its luck on the upper Missouri. The Blackfeet were waiting. Pilcher sent Robert Jones and Michael Immell to capitalize on the lucrative beaver trade. Obtaining large numbers of pelts each day, activities flowed smoothly unntil mid-May when 38 “friendly” Blackfeet arrived in camp. Immell successfully avoided and prevented any hostility from occurring. Fifteen days later, however, their luck ran out. Three hundred to four hundred Atsinas descended upon them and cut Immell to pieces. Jones’s body was riddled with arrows; five others died and four more were wounded. The Atsinas stole more than $15,000 worth of property. This mishap severely crippled the Missouri Fur Company.[23]Hiram M. Chittenden, American Fur Trade of the Far West, 2 vols. (New York: Press of the Pioneers, 1935), 1:148-51. For other incidents involving fur traders and Blackfeet, see LeRoy R. Hafen, The … Continue reading Survivors of the Immell-Jones massacre blamed the attacks on the British. The chief purportedly possessed a letter with the words “God Save the King” inscribed, which seemed to justify the Americans’ accusations.[24]Joshua Pilcher to Thomas Hempstead, 23 July 1823, in Dale L. Morgan, ed., The West of William H. Ashley (Denver: The Old West Publishing Co., 1964), 41. Clay J. Landry, “‘When Timely Apprised … Continue reading

Even if the British did not incite the Blackfeet to raid their American rivals—as the Americans believed—the British profited significantly since valuable beaver pelts with American stamps dominated the majority of furs that were exported to British posts on the Saskatchewan. Most importantly, Blackfeet continually traded stolen horses at British posts for tobacco and whiskey. British attempts to compete with their American rivals caused them to abandon their moderation policy in supplying liquor to the Blackfeet. Britain realized liquor motivated the Blackfeet to trap beaver. This was both profitable and dangerous as the viciousness and violent character of drunken Blackfeet had no rival.[25]Lewis, Effects of White Contact upon the Blackfoot Culture, 21.

The Rendezvous System

Blackfeet on the Warpath

Alfred Jacob Miller (1810–1874)

Watercolor on paper, 8 3/4 x 12 1/4 in. Courtesy the Gilcrease Museum.

The Blackfeet were so adept at stealing horses and furs and causing havoc that American trappers developed the rendezvous system, which allowed trappers to avoid Blackfeet territory throughout the 1820s.

Meanwhile, Blackfeet simultaneously attacked Ashley and Henry’s trappers near present-day Great Falls, Montana, killing four men and stealing numerous furs, traps, and horses. The company built a fort at the mouth of the Yellowstone but the Atsinas’ constant horse-raiding forced them to abandon it. Blackfeet were so adept at stealing horses and furs and causing havoc in Montana that Ashley and Henry decided to adopt a different system of collecting furs. Instead of using trading posts on the river to collect and transport furs and furnish men and Indians with supplies, they planned summer rendezvous that accomplished the same tasks. The pack trains would carry needed supplies into the Rockies during the summer that could be exchanged for furs from mountain men and friendly Indians, which the returning men sold in the fall.[26]Frederick R. Gowans, Rocky Mountain Rendezvous: 1825-1840 (Provo: Brigham Young University Press, 1976) is the major work on the rendezvous system and contains the best compilation of the major … Continue reading

The rendezvous system temporarily provided a solution to Blackfeet hostilities because the trappers avoided their territory throughout the 1820s. Jedediah Smith had wintered with the Crows on the east side of the Wind River Mountains in 1823. While there he learned about the Green River Basin, located on the other side of the mountains; not only was it rich in beaver, but the friendly Utes and Shoshones had not trapped the area. From 1824 to 1829, Americans and British trapped out present-day Utah, Idaho, and Wyoming. As beaver became scarce, trappers were forced to journey to Three Forks and the land of the Blackfeet in Montana.

By the late 1820s, Blackfeet did not distinguish between beaver trappers according to nationality as they previously had done.[27]The Atsinas had never cared for the British, only trading with them when they desired whiskey, for which they traded bison meat, horses, or furs. As early as 1811, they made plots against … Continue reading The North West Company had merged with the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1821. These British trappers continued their encroachment along American streams as beaver became scarce in Canada. They eagerly moved up the Snake River to trap streams out before the Americans had a chance to harvest any furs. Peter Skene Ogden of the Hudson’s Bay Company reported Blackfeet hostility against British as well as Americans during this time.[28]E.E. Rich, ed., Peter Skene Ogden’s Snake Country Journals, 1824-1828 (London: Publications of the Hudson’s Bay Record Society, 1950).

The 1820’s

Blackfeet hostilities toward the Long Knives increased in the 1820s as materialism permeated and undermined traditional Blackfeet culture. The fur trade created Blackfeet dependency on foreigners as inundation of western goods such as kettles, guns, awls, axes, knives, tobacco, and larger tepees made it necessary to acquire more furs and horses to exchange with British traders for these commodities. Horses also could be used to purchase additional wives, which were necessary to handle the increased burden of preparing provisions and tanning hides. Female labor turned idle capital (surplus horses) into productive capital (women). The easiest way to acquire women was to steal them from other tribes or to trade horses for them. Stealing from Americans provided the Blackfeet with furs and horses. To a Blackfeet warrior, horses could be exchanged for anything in life worth having; therefore, one could never capture enough of them.[29]Blackfeet, as well as other tribes who stole horses, walked to enemy camps and rode the horses they stole to escape. While Blackfeet parties traveled on foot, mountain men and Indians sometimes … Continue reading

Magnificent warriors, the Blackfeet excelled at horse larceny. The desire to acquire horses and scalps increased an individual’s personal wealth and fulfilled part of his initiation process to become an acceptable warrior within the nation. Many skirmishes during the rendezvous period consisted of Blackfeet attempts to take horses and furs from Americans. The Blackfeet raiders traded horses and furs they stole from Americans for British goods, guns, whiskey, and tobacco. The Atsinas, in particular, mastered horse larceny. They were among the most numerous and feared northern plains people. Contact between Atsinas and trappers occurred frequently—much too frequently for the trappers. Many trappers often developed a bad case of “Blackfeet Fever,” which caused them to mistake herds of antelope and bison for a Blackfeet war party. Meanwhile, actual failure to detect Atsina raiders often resulted in death. Alexander Henry described the Atsinas as a “most audacious and turbulent race, and have repeatedly attempted to destroy and massacre us all.”[30]Gough, ed., Journal of Alexander Henry the Younger, 381. Ranging up and down both sides of the Rockies, particularly the Three Forks area, Atsinas and mountain men clashed repeatedly.[31]In 1837, Alfred Jacob Miller estimated Blackfeet killed between 40 and 50 mountain men a year during the fur trade. Marvin C. Ross, ed., The West of Alfred Jacob Miller (Norman: University of … Continue reading

Atsinas visited their Arapaho kinsmen in present-day Wyoming and Colorado during the summer months, leading to disputes and confrontations with Americans along traditional travel routes. Atsinas hunted bison on the Wyoming plains and ventured as far south as Santa Fe, capturing mustangs between the Platte and Arkansas rivers.[32]David Lavender, Bent’s Fort (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1954), 121, 125. Atsinas realized the rendezvous strengthened their rivals, providing armaments and supplies to Shoshones, Utes, Crows, Flatheads, and Nez Perces. Large horse herds accompanied the rendezvous as hundreds of mountain men and thousands of Indians gathered for games and recreation. These horses proved tempting targets for Indians skilled at the deadly but exciting game of grand theft cayuse.

As could be expected, several violent encounters occurred during summer rendezvous. James Beckwourth gave an excellent first-hand account of the 1827 rendezvous at Sweet Lake (present-day Bear Lake) on the Utah-Idaho border. A Blackfeet party surprised and killed ve Shoshones. Shoshone Chief Cut Face asked the American trappers to show their friendship and loyalty by assisting the Shoshones in mounting a counter-attack. William Sublette gathered nearly three hundred trappers and charged the enemy. After a six-hour battle the Blackfeet retreated, abandoning many of their dead—an unusual occurrence because of the almost certain mutilation that awaited the deceased. Beckwourth recorded the fruits of their victory to be 173 Blackfeet scalps, and numerous weapons. The following year, in 1828, a repeat attack nearly occurred in the same location. Blackfeet abandoned the field when reinforcements from the rendezvous arrived before any bloodshed took place.[33]Thomas Bonner, The Life and Adventures of James P. Beckwourth, Mountaineer, Scout, Pioneer and Chief of the Crow Nation of Indians, ed. Charles G. Leland (London: T.F. Unwin; New York: Macmillan, … Continue reading

The 1830’s

In 1830, artist George Catlin observed, “The Blackfoot, are, perhaps, the most powerful tribe on the continent.” Even though American trappers attempted to incorporate a profitable trade system, Catlin recognized the Blackfeet Confederacy’s strength and saw them stubbornly resist fur traders. Catlin noted the country “abounds with beaver and buffalo and others.” Yet he lamented the destruction of the beaver. “The Blackfoot have repeatedly informed the traders of the company that if this persists they will kill the trappers. The company lost 15-20 men. The Blackfoot therefore have been less traded with and less seen by whites and less understood.”[34]George Catlin, Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Conditions of the North American Indians, 2 vols. (1841; New York: Dover, 1973), 1: 51-52. In 1832, Catlin estimated the three tribes … Continue reading

Perhaps the most significant rendezvous battle occurred at the 1832 Battle of Pierre’s Hole. The Atsina attackers consisted of fifty men plus several women and children and, as the Indians advanced, a British flag flapped in the breeze.[35]Jim Hardee, Pierre’s Hole!: The Fur Trade History of Teton Valley, Idaho (Pinedale, WY: Sublette County Historical Society, 2010), 187-262. A small brigade under Milton Sublette and two other parties had left the rendezvous on 17 July . This party of 41 men proceeded up the hills to the southeast, headed for Teton Pass. The next morning they looked up toward the pass and saw a group of travelers, whom they assumed to be one of the supply trains that had not arrived at the rendezvous.[36]This same group of Atsinas had attacked Thomas Fitzpatrick the week before and had stolen his horses. After escaping with his life, Fitzpatrick eventually made it to the rendezvous. His horses were … Continue reading The Atsina chieftain rode out to meet the trappers. An Iroquois named Antoine Godin rode his horse out to meet him. Godin, whose father had been brutally murdered by Blackfeet, raised his gun and shot the Atsina chieftain.[37]Washington Irving, The Adventures of Captain Bonneville, U.S.A., In the Rocky Mountains and the Far West (New York: G.P. Putnam, 1859), 73-80.

The previous week, this same group of Atsinas had attacked Thomas Fitzpatrick and taken his horses. George Nidever relates how the Atsinas made a fortification in the willows and fought tenaciously against the trappers and allies. The Atsinas fled the scene when several hundred reinforcements from the rendezvous arrived. Three mountain men and five Indian allies died. Accounts list Atsina casualties between 27 and 50 dead.[38]William Henry Garrison, ed., The Life and Adventures of George Nidever (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1937), 26-30. Ironically, this same year a group of Piegans had signed a treaty with the American Fur Company to allow Kenneth McKenzie to build a fort there the following year, provided the Indians would trap the beaver and trade at the post.[39]David J. Wishart, The Fur Trade of the American West, 1807-1840: A Geographical Synthesis (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1979), 61n. Jacob Berger, the treaty mediator, had traded with the … Continue reading Built in 1831, Fort Piegan became the first fort in Blackfeet lands of which the Piegans approved. The following year, however, Bloods or Atsinas burned it down. In 1833, McKenzie built Fort McKenzie near the confluence of the Marias and Missouri rivers.[40]For Blackfeet involvement in the fur trade, see Eugene Y. Arima, Blackfeet and Palefaces: The Pikani and Rocky Mountain House (Ottawa: Golden Dog Press, 1995); Robert K. Doerk, Jr., The Fur and Robe … Continue reading

Smallpox Wins

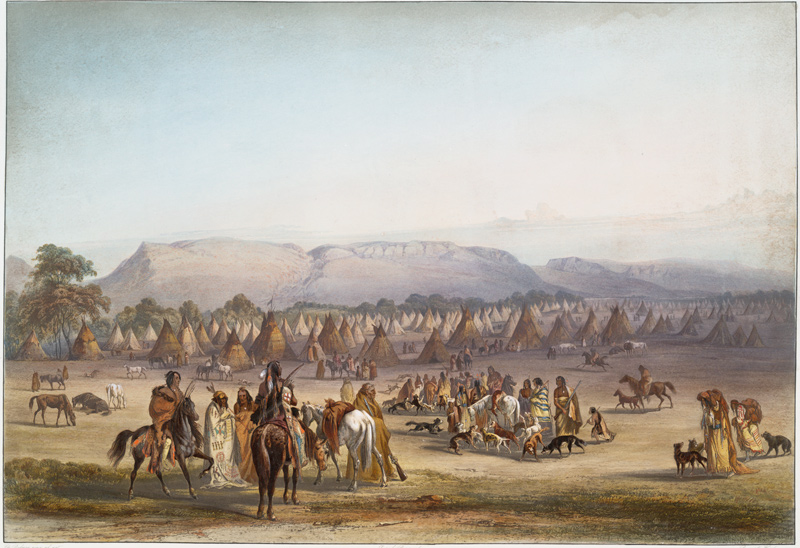

Encampment of the Piekann Indians

Karl Bodmer (1809–1893)

Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library.[41]“Lager der Piekann Indianer. Camp des Indiens Piekann. Encampment of the Piekann Indians.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed December 14, 2020. … Continue reading

In 1837, Blackfeet stole blankets contaminated with smallpox from a steamboat at Fort Union and brought them back to their village near Fort McKenzie. As many as 6,000 Blackfeet died as the epidemic spread throughout the area.

This new fort achieved immediate success by offering Blackfeet the chance to trade and barter. A chief had told John Sanford, Indian agent for the upper Missouri tribes, “If you will send Traders into our Country we will protect them and treat them well; but Trappers—Never.”[42]Francois Chardon, Journal at Fort Clark, 1834-1836, ed. by Annie H. Abel (South Dakota: Department of History, State of South Dakota, 1932), 253. Unfortunately, this fort unwittingly spread the deadly smallpox epidemic that journeyed upriver in 1837 aboard the St. Peters steamboat. Smallpox spread as far as Fort Union where infected trade goods were transferred to another vessel heading for Fort McKenzie. The post commander there, Alexander Culbertson, quarantined the infected vessel to prevent the epidemic from spreading; however, the Blackfeet felt the Americans were discriminating against them by withholding trade commodities, particularly a shipment of guns they needed to fight the Crows and Flatheads.[43]Leslie Wischmann, Frontier Diplomats: Alexander Culbertson and Natoyist-Siksina’ among the Blackfeet (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2000), 67-76.

Several Blackfeet snuck on board and removed infected blankets that contaminated their village near the fort. As the tribes dispersed, they spread the epidemic. Perhaps as many as 6,000 Blackfeet, roughly half of their population, died in this outbreak. This debilitating plague marked a numerical decline that ended Blackfeet domination of the northern plains. Consequently, by fall, the Blackfeet concerned themselves more with survival than with fighting Americans. After 1837, mountain men often followed Blackfeet to fight them in their weakened condition. However, only minor confrontations occurred as the beaver trade drew to a close and bison robes became the new trading commodity at the forts.[44]Ewers, The Horse in Blackfoot Culture, 65-66. See also Chardon, Journal at Fort Clark; K. C. Tessendorf, “Red Death on the Missouri, The Tragic Smallpox Epidemic of 1837,” The American … Continue reading

Summary

Between 1806 and 1840, the northern location of the Blackfeet Confederacy had brought them into contact with British trappers who formed alliances with them. These bonds provided the British with an easy way to expel Americans—by encouraging Blackfeet to attack Americans to take their horses, furs, and guns. The Americans failed to learn from the British how to trade effectively with the Blackfeet. Whereas the British built posts on the outskirts of Blackfeet territory and sent representatives to trade with the nations, Americans chose to invade the territory and trap fur-bearing animals themselves. In addition, Americans built trading posts and forts in Blackfeet territory, often without permission, traded with their traditional enemies, and often intermarried with those tribes, becoming enemies through kinship. Blackfeet disliked trapping themselves and found it immensely easier to steal furs and horses from the Americans and trade them with the British to meet their rising materialistic tendencies. Blackfeet capitalistic ventures often ended in violent confrontations with American and, later, British trappers. To compound the problem, trappers depleted the beaver, bison, and other fur and hide bearing animals and introduced diseases that killed more Blackfeet than bullets or big knives ever did.

The inclusion of the Atsinas in the Blackfeet Confederacy brought frequent encounters with Americans as they both traversed the northern and central Rockies. Atsina depredations forced Americans to desert the upper Missouri and venture overland to reach trapping streams. These supply routes of the rendezvous caravans opened the way for the overland migrations of the 1840s and 1850s along the Great Fur Trade Road. After more than half a century of conflict, diplomats for the United States and for the Blackfeet Nation met at a council held on 17 October 1855, near the mouth of the Judith River. They agreed to a treaty setting aside a reservation for the Blackfeet in what became Montana. The Blackfeet represented the last Great Plains Indian nation to enter into a treaty with the United States, which ushered in a new era between the Blackfeet and the Big Knives.[45]“Treaty with the Blackfeet, 1855,” in Charles J. Kappler, ed., Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties, 5 vols. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1904), 2:736-40.

Notes

| ↑1 | Jay H. Buckley, “Short Tempers and Long Knives: Hostilities Between the Blackfeet Confederacy and American Fur Trappers from 1806 to 1840,” We Proceeded On, May 2013, Volume 39, No. 2, the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. The original article is provided at https://lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol39no2.pdf#page=9. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | “Blackfoot Indianer zu Pferd. Indien Pieds Noir à cheval. A Blackfoot Indian on horse-back.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed 14 December 2020. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-c401-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99. |

| ↑3 | The term Blackfeet referred to northwestern plains nations who sometimes wore black moccasins dyed with paint or darkened with ashes. J. Cecil Alter, James Bridger (Columbus, OH: Long’s College Book Co., 1951), 6. “Original People,” “Real People,” and “Prairie People” are some renderings of their national identity. [See on this site Blackfoot People.] The author thanks reviewer Gary Moulton and proofreaders Carl Camp and Jerry Garrett for their assistance with this article. |

| ↑4 | Helen B. West, Meriwether Lewis in Blackfeet Country, Bureau of Indian Affairs, Blackfeet Agency (Browning, MT: Museum of the Plains Indian, 1964). [See also on this site Fight on the Two Medicine and The Marias River Risk.] |

| ↑5 | Horse stealing represented the central focus of Plains Indian culture. Alexander Henry regarded the Blackfeet tribes as the “most independent and happy people of all the tribes East of the Rocky Mountains. War, women, horses and buffalo are their delights, and all these they have at [their] command.” Elliott Coues, ed., New Light on the Early History of the Greater Northwest: The Manuscript Journals of Alexander Henry and David Thompson, 1799-1814, 3 vols. (New York: Francis P. Harper, 1897), 2:737. For an in-depth study, see John C. Ewers, The Horse in Blackfoot Culture (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1955). |

| ↑6 | Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition, 13 vols. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983-2001), 8:127-37, esp. 134-35; John C. Jackson, “The Fight on Two Medicine River: Who Were Those Indians, and How Many Died?” We Proceeded On, 32:1 (February 2006), 14-23, available at https://lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol32no1.pdf#page=15; Robert A. Saindon, “The ‘Unhappy Affair’ on Two Medicine River: Were the Indians with Whom Lewis Tangled Blackfeet or . . . Gros Ventres of the Prairie?” We Proceeded On, 28:3 (August 2002), 12-25, https://lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol28no3.pdf#page=13; Arlen J. Large, “Riled-up Blackfeet: Did Meriwether Lewis Do It?” We Proceeded On, 22:4 (November 1996), 4-11, https://lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol22no4.pdf#page=4; and Paul R. Cutright, “Lewis on the Marias 1806,” Montana: The Magazine of Western History, 18:3 (1968), 30-43. |

| ↑7 | David Thompson, David Thompson’s Narrative of His Explorations in Western America, 1784-1812 (Toronto: Champlain Society, 1916), 375. See also Ted Binnema, “Allegiances and Interests: Niitsitapi (Blackfoot) Trade, Diplomacy, and Warfare, 1806-1831,” Western Historical Quarterly, 37 (Autumn 2006), 327-49; Ted Binnema and William A. Dobak, “‘Like a Greedy Wolf’: The Blackfeet, the St. Louis Fur Trade, and War Fever, 1807-1831,” Journal of the Early Republic, 29 (Fall 2009), 411-40, esp. 415; Peter W. Dunwiddie, “The Nature of the Relationship between the Blackfeet Indians and the Men of the Fur Trade,” Annals of Wyoming, 46 (Spring 1974), 123-33; Paul Raczka, “Posted: No Trespassing: The Blackfoot and the American Fur Trappers,” in Selected Papers of the 2010 Fur Trade Symposium, Jim Hardee, ed. (Three Forks, MT: Three Forks Area Historical Society, 2011), 140-48. The Algonquian word for “big knives” is provided by William Anderson in Dale L. Morgan and Eleanor T. Harris, eds., The Rocky Mountain Journals of William Marshall Anderson, The West in 1834 (San Marino, CA: The Huntington Library, 1967), 233. |

| ↑8 | The tribal designation in Canada is always Blackfoot while many American fur trade references use the term Blackfeet, which I have done to avoid going back and forth. Donald Ward, “Blackfoot Confederacy,” in The People: A Historical Guide to the First Nations of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba (Markham, ON: Fifth House Books, 1995), 24-56; Hugh A. Demsey, “Blackfoot,” in Plains, vol. 13 of the Handbook of the North American Indians, edited by Raymond J. DeMallie (Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 2001), vol. 13, part 1, 604-28; Loretta Fowler and Regina Flannery, “Gros Ventre,” in Plains, vol. 13 of the Handbook of the North American Indians, edited by Raymond J. DeMallie (Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 2001), vol. 13, part 2, 677-94. |

| ↑9 | John Jacob Astor’s men traded firearms to Flathead Indians in 1810. Heretofore, these tribes had been forced by the Blackfeet to travel all the way to the Missouri and trade with the Hidatsas and Mandans. The balance of power equalized as Blackfeet lost several Indian battles with their enemies to the west and south between 1810 and 1812. Oscar Lewis, The Effects of White Contact upon the Blackfoot Culture, with Special Reference to the Role of the Fur Trade (New York: J.J. Augustin, 1942), 20. |

| ↑10 | John C. Ewers, The Blackfeet: Raiders on the Northwestern Plains (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1958), 21-22. |

| ↑11 | Many years after the encounter, Wolf Calf claimed to have been a member of this Piegan raiding party and offered his account of the incident. Olin D. Wheeler, The Trail of Lewis and Clark, 1804—1904, 2 vols. (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904), 2:311-12. See Frederick E. Hoxie and Jay T. Nelson, eds., Lewis and Clark and the Indian Country: The Native American Perspective (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2007), 168-79; John C. Jackson, The Piikani Blackfeet: A Culture Under Siege (Missoula: Mountain Press Publishing Company, 2000), 56-57; and Eric Newhouse, “Blackfeet recollections differ from those recorded in Lewis’s journal,” Great Falls Tribune, 23 April 2003; A film, A Blackfeet Encounter, directed and produced by Dennis Neary (Lincoln: Vision Maker Media, 2007) combines Blackfeet and expedition viewpoints: http://www.visionmaker. org/stream/a_blackfeet_encounter. |

| ↑12 | Manuel Lisa already had learned about the wealthy tribes of the West, the Arapahos on the Platte, the Crows of the Yellowstone, and the Blackfeet of the upper Missouri. Richard E. Oglesby, Manuel Lisa and the Opening of the Missouri Fur Trade (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1963), 34. See also Larry E. Morris, The Fate of the Corps: What Became of the Lewis and Clark Explorers After the Expedition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004); Frank H. Dickson, “Hard on the Heels of Lewis and Clark,” Montana The Magazine of Western History, 26 (Winter 1976),14-25; Charles E. Hanson, Jr., “Expansion of the Fur Trade Following Lewis and Clark,” We Proceeded On, Supplemental Publication, 4 (December 1980), 21-28; and Hardee, ed., Selected Papers of the 2010 Fur Trade Symposium. |

| ↑13 | Alexander Henry recorded on 14 September 1808, at Rocky Mountain House in Canada that “Last year, it is true, we got some beaver from them; but this was the spoils of war, they having fallen upon a party of Americans on the Missourie, stripped them of everything, and brought off a quantity of skins.” Barry M. Gough, ed., The Journal of Alexander Henry the Younger, 1799-1814 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1992), 2:541. |

| ↑14 | Thomas James, Three Years among the Indians and Mexicans, ed. by Walter B. Douglas (St. Louis: Missouri Historical Society, 1916), 52-53. |

| ↑15 | Colter’s famous race for life is masterfully chronicled by Thomas James as he heard the story from Colter while they trapped beaver together on the Three Forks. James, Three Years among the Indians and Mexicans, 58-65. For Colter’s narrow escapes from Blackfeet, see Reuben G. Thwaites, ed., Early Western Travels, 1748-1846 (Cleveland: Arthur H. Clark Company, 1904), 5:44-47. Colter biographers include Burton Harris, John Colter: His Years in the Rockies (1952, reprint; Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1993); and L. Ruth Colter-Frick, Courageous Colter and Companions (Washington, MO: Video Proof, 1997). [See also on this site, Lisa’s Fur Trade Forts.] |

| ↑16 | The Crows, with new American muzzle-loaders, defeated a party of Atsinas on the Yellowstone River. This was an unprecedented event that resulted in constant retaliation by the Atsinas in an attempt to drive the Americans out and burn down their posts. |

| ↑17 | James, Three Years among the Indians and Mexicans, 82-83; and M.O. Skarsten, George Drouillard: Hunter and Interpreter for Lewis and Clark and Fur Trader, 1807-1810 (Glendale, CA: Arthur H. Clark Company, 1964), 301-04, 309-11. |

| ↑18 | Ewers, Blackfeet, 50. |

| ↑19 | Oglesby, Manuel Lisa and the Opening of the Missouri Fur Trade, 115. |

| ↑20 | Reuben Lewis to Meriwether Lewis, April 21, 1810, Meriwether Lewis Collection, Missouri Historical Society Archives, St. Louis, Missouri. |

| ↑21 | Kenneth A. Spaulding, ed., On the Oregon Trail: Robert Stuart’s Journey of Discovery, 1812-1813 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1953), 94. |

| ↑22 | Kate L. Gregg, “The War of 1812 on the Missouri Frontier,” Missouri Historical Review (Part 1, October 1938; Part 2, January 1939; part 3, April 1939), 3, 16, 327. Gregg’s three articles contain an excellent overview of the impact of the War of 1812 on natives and the tension between the British and Americans. |

| ↑23 | Hiram M. Chittenden, American Fur Trade of the Far West, 2 vols. (New York: Press of the Pioneers, 1935), 1:148-51. For other incidents involving fur traders and Blackfeet, see LeRoy R. Hafen, The Mountain Men and the Fur Trade of the Far West, 10 vols. (Glendale, CA: Arthur H. Clark Company, 1965-1972). |

| ↑24 | Joshua Pilcher to Thomas Hempstead, 23 July 1823, in Dale L. Morgan, ed., The West of William H. Ashley (Denver: The Old West Publishing Co., 1964), 41. Clay J. Landry, “‘When Timely Apprised of His Danger, A Host Within Himself!’ Michael Immell, Fur Man,” in Selected Papers of the 2010 Fur Trade Symposium, Hardee, ed., 184-99. |

| ↑25 | Lewis, Effects of White Contact upon the Blackfoot Culture, 21. |

| ↑26 | Frederick R. Gowans, Rocky Mountain Rendezvous: 1825-1840 (Provo: Brigham Young University Press, 1976) is the major work on the rendezvous system and contains the best compilation of the major battles involving Blackfeet Indians. |

| ↑27 | The Atsinas had never cared for the British, only trading with them when they desired whiskey, for which they traded bison meat, horses, or furs. As early as 1811, they made plots against Hudson’s Bay Company posts. The Piegans and other tribes of the confederacy usually warned the Hudson’s Bay Company men when Atsinas were coming so the men could prepare for their arrival. The Atsinas were “the most notorious thieves, and when we hear of a band coming in to trade, every … moveable European article must be shut up.” Coues, ed., New Light on the Early History, 378. |

| ↑28 | E.E. Rich, ed., Peter Skene Ogden’s Snake Country Journals, 1824-1828 (London: Publications of the Hudson’s Bay Record Society, 1950). |

| ↑29 | Blackfeet, as well as other tribes who stole horses, walked to enemy camps and rode the horses they stole to escape. While Blackfeet parties traveled on foot, mountain men and Indians sometimes gained and exploited this Blackfeet weakness and lack of mobility by attacking them. See Lewis, Effects of White Contact upon the Blackfoot Culture, 36-40; also, George Bird Grinnell, Blackfoot Lodge Tales: The Story of a Prairie People (1892; reprint, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1962), 242-55. |

| ↑30 | Gough, ed., Journal of Alexander Henry the Younger, 381. |

| ↑31 | In 1837, Alfred Jacob Miller estimated Blackfeet killed between 40 and 50 mountain men a year during the fur trade. Marvin C. Ross, ed., The West of Alfred Jacob Miller (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1951), 148. |

| ↑32 | David Lavender, Bent’s Fort (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1954), 121, 125. |

| ↑33 | Thomas Bonner, The Life and Adventures of James P. Beckwourth, Mountaineer, Scout, Pioneer and Chief of the Crow Nation of Indians, ed. Charles G. Leland (London: T.F. Unwin; New York: Macmillan, 1892), 103-8. Indian tribes believed mutilated bodies would not return to perfect form in the resurrection. Therefore, mutilating an enemy’s body would save them the trouble of fighting them again in the next life. |

| ↑34 | George Catlin, Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Conditions of the North American Indians, 2 vols. (1841; New York: Dover, 1973), 1: 51-52. In 1832, Catlin estimated the three tribes (Blackfoot, Bloods, Piegans) numbered 1,650 lodges. Add to that, approximately three hundred Atsina lodges. By taking the accepted estimation theory of eight to ten persons per lodge, the 1832 Blackfeet population totaled nearly 19,500. |

| ↑35 | Jim Hardee, Pierre’s Hole!: The Fur Trade History of Teton Valley, Idaho (Pinedale, WY: Sublette County Historical Society, 2010), 187-262. |

| ↑36 | This same group of Atsinas had attacked Thomas Fitzpatrick the week before and had stolen his horses. After escaping with his life, Fitzpatrick eventually made it to the rendezvous. His horses were among those taken after the Atsinas had fled. LeRoy R. Hafen, Broken Hand: The Life of Thomas Fitzpatrick (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1981), 106-20. |

| ↑37 | Washington Irving, The Adventures of Captain Bonneville, U.S.A., In the Rocky Mountains and the Far West (New York: G.P. Putnam, 1859), 73-80. |

| ↑38 | William Henry Garrison, ed., The Life and Adventures of George Nidever (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1937), 26-30. |

| ↑39 | David J. Wishart, The Fur Trade of the American West, 1807-1840: A Geographical Synthesis (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1979), 61n. Jacob Berger, the treaty mediator, had traded with the Blackfeet for many years. |

| ↑40 | For Blackfeet involvement in the fur trade, see Eugene Y. Arima, Blackfeet and Palefaces: The Pikani and Rocky Mountain House (Ottawa: Golden Dog Press, 1995); Robert K. Doerk, Jr., The Fur and Robe Trade in Blackfoot Country: 1831-1880 (Fort Benton: River and Plains Society, 2003); and John G. Lepley, Blackfoot Fur Trade on the Upper Missouri (Missoula, MT: Pictorial Histories Publishing Company, 2004). |

| ↑41 | “Lager der Piekann Indianer. Camp des Indiens Piekann. Encampment of the Piekann Indians.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed December 14, 2020. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-c466-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99 |

| ↑42 | Francois Chardon, Journal at Fort Clark, 1834-1836, ed. by Annie H. Abel (South Dakota: Department of History, State of South Dakota, 1932), 253. |

| ↑43 | Leslie Wischmann, Frontier Diplomats: Alexander Culbertson and Natoyist-Siksina’ among the Blackfeet (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2000), 67-76. |

| ↑44 | Ewers, The Horse in Blackfoot Culture, 65-66. See also Chardon, Journal at Fort Clark; K. C. Tessendorf, “Red Death on the Missouri, The Tragic Smallpox Epidemic of 1837,” The American West, 14:1 (January/February 1977), 48-53; and Morgan, The West of William H. Ashley, 263. |

| ↑45 | “Treaty with the Blackfeet, 1855,” in Charles J. Kappler, ed., Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties, 5 vols. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1904), 2:736-40. |