In lieu of a portrait of Pursh, of which none are known to exist, it seems appropriate to represent him by one of the hand-colored engravings that he published in his Flora Americae septentrionalis (Flowers of North America) in 1813. Undoubtedly it was the unusual shape of its petals, and its striking color, that inspired Lewis to call it “a singular plant”. Pursh, the first laboratory or “cabinet” botanist to describe the elkhorn in proper terms and details, officially named it Clarkia pulchella—”Beautiful Clarkia”—in honor of William Clark.

—Joseph Mussulman

The short life of Frederick Pursh (also known as Friedrick Pursch) is a tale of emotional and professional highs and lows, fortune and misfortune, and triumphs and tragedies. He survives in botanical history by virtue of a single book, his Flora americae septentrionalis. He lies dead in an unmarked grave somewhere in Montreal, Canada, a drunk and destitute at the end of life.

Pursh was born at Grossenhain in Saxony in unknown circumstances. Apparently he received little in the way of a formal education and probably in his late teens took employment at the Royal Botanic Gardens in Dresden. There he inherited a manuscript on the plants of the area that he prepared for publication. The work was published in parts by W. G. Becker in Der Plauische Grund bei Dresden, mit Hinsicht auf Naurgeschichte und schöne Gartenkunst in 1799. The title of Pursh’s contribution was “Verzeichniss der im Plauischen Grunde und den zunächst angrenzenden Gegenden wildwachsenden Pflanzen,” and here he rendered his name “Friedrich Traugott Pursch.”

Flushed with the success of his contribution, Pursh left Germany for the new United States. The reason for his departure is unknown, but his work in Dresden may have stirred a desire to see other parts of the world, and especially a part that offered a wealth of new and exciting plants for the garden.

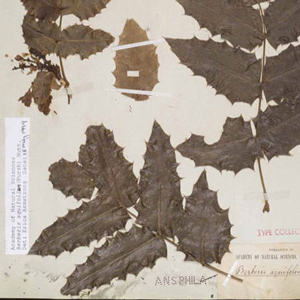

Pursh’s silky lupine, Lupinus sericeus Pursh

Collected near Kamiah, Idaho Co., Idaho, on 5 June 1806

Photo © 2000 James L. Reveal.

Lance-leaf springbeauty, Claytonia lanceolata Pursh

Collected along the Lolo Trail, Idaho Co., Idaho, 25-27 June 1806

© 2000 James L. Reveal.

Scarlet gilia, Ipomopsis aggregata (Pursh) V. E. Grant

Collected along the Lolo Trail, Idaho Co., Idaho, 26 June 1806

Photo © 2000 by James L. Reveal.

Great purple monkey-flower, Mimulus lewisii Pursh

Found at “the head springs of the Missouri,” 12 August 1805

Photo © 2000 by James L. Reveal.

Elegant Mariposa-lily, Calochortus elegans Pursh

Collected near Kamiah, Idaho Co., Idaho, on 17 May 1806

Photo © 2000 by James L. Reveal.

Pinkfairies, Clarkia pulchella Pursh

Found “on the steep sides of the fertile hills” northeast of Kamiah, Idaho Co., Idaho, on 1 June 1806

Photo © 2000 James L. Reveal.

Oregon bitterroot, Lewisia rediviva Pursh

Collected near Travelers’ Rest, Missoula Co., Montana, on 2 Jul 1806

Photo © 2000 James L. Reveal.

Great blanket-flower, Gaillardia aristata Pursh[1]Nuttall named this species Virgilia grandiflora (ver-JILL-ee-ah gran-DEE-floor-ah) in his 1813 listing of plants in Fraser’s catalogue. Later in the year, Pursh proposed Gaillardia aristata … Continue reading

Photo ©2000 James L. Reveal.

Collected “on dry hills” along Beaver Creek near Lewis and

Clark Pass, Lewis and Clark Co., Montana, 7 July 1806

Collected along the Lolo Trail, Idaho Co., Idaho, on 15 June 1806; on 16 June 1806 Lewis wrote “the dog-tooth violet is just in blume.”

Prairie flax, Linum lewisii Pursh

Found in the “Valleys of the Rocky mountains” on 9 July 1806

Photo © 2000 James L. Reveal.

American Gardener

Pursh reached the American shore in 1799 and quickly found employment, apparently at a newly established botanical garden near Baltimore where he had the title of manager. Supposedly this was at “Canton”—an estate house owned by Colonel John O’Donnell—but his stay was probably not much over a year. It is clear that by 1801, Pursh was in Philadelphia and at “Springhill” in the employment of Samuel Beck as a gardener. Today, Springhill is part of Fairmount Park. In September of 1801, Pursh wrote to Benjamin Smith Barton[2]Benjamin Smith Barton was born in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, on February 10, 1766, the son of the Reverend Thomas Barton and Ester Rittenhouse Barton. His mother was the daughter of American astronomer … Continue reading that he was working as a “slave” for Beck, and looking for another opportunity. When, and if, Pursh was associated with Henry Pratt’s garden at “Lemon Hill” (now also part of Fairmount Park) is uncertain.

By 1803, Pursh was at “The Woodlands,” the grand estate of William Hamilton, where he succeeded the noted gardener John Lyon, for whom the shrub genus Lyonia (lie-ON-ee-ah) was named. It was at this time that Pursh came to know such botanists as Philadelphia’s William Bartram,[3]No Philadelphia family is better known in botanical circles than the Bartrams. Certainly more books have been written about John Bartram (1699-1777) and William Bartram (1739-1823) than any other … Continue reading the son of the “King’s botanist” John Bartram, and the Reverend Gotthilf Henry Ernest Muhlenberg[4]Henry Muhlenberg was born in 1753, the year the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus published Species plantarum [plan-TAR-um] and began our modern system of naming plants. Schooled in Philadelphia as a … Continue reading of Lancaster. For years Muhlenberg had been working on the local flora, sending specimens and descriptions of new species to Europe for publication.

These men provided Pursh with numerous opportunities to read in their libraries, to consult their gardens and herbaria, and to talk of the American flora. However, it would be Benjamin Smith Barton who would provide Pursh with his escape from the drudgery of working in the garden.

Barton was a romantic with grand notions of self-importance and accomplishments. In 1805, Pursh left Woodlands and became Barton’s part-time curator and collector. Barton’s goal was to build a huge herbarium of American plants and then produce a new flora of North America. That such a book had been published in 1803 by the French botanist André Michaux—his two-volume work Flora boreali-Americana—seemed to be only a minor irritant. The following year, Pursh was in Virginia collecting plants, being away from Philadelphia from mid-April until November.

Lewis and Clark Specimens Arrive

In 1805, Thomas Jefferson received the first 60 plants Meriwether Lewis had collected along the Missouri River in 1804. They had been assembled at Fort Mandan, the 1804-1805 site in what is now North Dakota where the expedition over-wintered and, with a detailed catalogue, seeds and some live specimens, the whole had been sent back to St. Louis in the spring of 1805. They eventually reached Jefferson in August. By mid-November, Jefferson had the dried specimens transmitted to Barton for his examination.

No doubt Pursh saw the collection when it arrived.

The relationship between Jefferson and Barton was a long-established one. Both men were members of the American Philosophical Society, and both had long wished someone would explore the western interior of North America for its natural wonders.[5]Thomas Jefferson had long wished to get a naturalist to explore the vast western part of North America. A vicarious westerner, Jefferson believed if a reasonable route could be found across the … Continue reading Barton’s overly ambitious plans for a flora of North America would have appealed to Jefferson. Certainly, Barton had some skill and knowledge in botany as his botanical publications had demonstrated. His set of essays on the materia medica of the United States, first published in 1798, and his brief report on the natural history of Pennsylvania (1799) attested to his general knowledge in the sciences. However, it was his Elements of botany: or outlines of the natural history of vegetables—the first American botany textbook—that firmly established Barton’s reputation. Thus, it was to Barton that Jefferson sent his private secretary, Meriwether Lewis, for instructions in botany in May and June of 1803.

Jefferson, and also Lewis, presumed Barton would play an active role in the preparation of a planned natural history volume that was to be part of Lewis’s report on the expedition. This was not to be. Barton did essentially nothing with the first set of plants although Lewis had provided him with abundant notes and material. With the return of the expedition in 1806, Jefferson urged Lewis to begin immediately to prepare his journal for publication, and to arrange with Barton to start, equally promptly, on the natural history. Apparently it was the noted Philadelphia gardener and seed merchant, Bernard M’Mahon[6]Bernard M’Mahon (or McMahon, 1775-1816) was an Irish-born American horticulturalist and owner of a large commercial garden in Philadelphia. Under Jefferson’s instructions, the seeds … Continue reading who, on 5 April 1807, recommended that Lewis contact Pursh to examine the expedition’s plants.

Why Barton was unable to do the task has been variously given as poor health or simple unwillingness. The latter seems more likely. As was so often the case with Barton, when called upon to actually produce, he rarely was able to do so. Clearly, M’Mahon understood this, and thus the recommendation of Pursh.

Cataloging the Expedition’s Plants

Lewis and Pursh met in Philadelphia by mid-April of 1807 and Pursh was employed to prepare a catalogue of the expedition’s plants. Receiving $60 from Lewis to begin the work, apparently Pursh first did a series of drawings with Lewis reviewing the results. Clearly the two men talked about the overall aspect of some of the species, but Lewis’s time was limited and Pursh was scheduled to leave at the end of April on his second collecting trip under Barton’s patronage. Only limited progress on the plants was made at that time.

During the winter of 1807-1808, Pursh lived at the home of Bernard M’Mahon in Philadelphia. Here he worked on the drawings and descriptions of Lewis’s western plants. By the end of May 1808, Pursh had completed the initial work and was anxious to see his report—or at least the new species—published. Pursh was also anxious to be paid for his labors.

The relationship between Pursh and Barton was beginning to strain. In January of 1809, M’Mahon wrote to Jefferson reporting Pursh’s displeasure at the delay in publication. To what extent Barton felt he (and Lewis) had hired Pursh to do a job, and that it would be Barton who would publish the new species, was probably also a factor. Soon thereafter, M’Mahon recommended Pursh to Dr. David Hosack[7]The name of Dr. David Hosack (1769-1835) shows up in many different places in American history. Besides establishing the Elgin Botanic Garden on what is now Rockefeller Plaza in New York City, he was … Continue reading of New York, who had just started the Elgin Botanic Garden and was in need of a gardener. By April of that year, Pursh left Philadelphia and was heading for New York. He took along a significant portion of the Lewis and Clark plant collection, most of his drawings, and apparently all of his notes

Lost Specimens

How it came that Pursh carried part of the collection with him to New York and, after a falling out with Hosack late in 1811, took it to London, has never been fully answered. The events and circumstances are still being researched, and perhaps new evidence will come to light while the nation celebrates the Lewis and Clark bicentennial.

The death of Lewis on 18 October 1809, was soon made known to Pursh. There is indirect evidence that, by this date, Pursh had completed his study of whole of the Lewis and Clark plant collection. In January 1810, Clark was looking for the plants and drawings in Philadelphia. He recovered the portion then in the possession of Bernard M’Mahon; these eventually were returned to the American Philosophical Society. He probably paid Pursh for the finished drawings, but it is not certain he ever received the plates. Some of Pursh’s ink sketches are now at the American Philosophical Society, but none of them is what one might consider a finished plate.

It is unclear what Clark did immediately with the plants he received from M’Mahon. It is possible they went back to Barton in the hopes he would still prepare a report on them for the expedition’s report. It is also possible Clark returned them to the Philosophical Society. At any rate, at some time, the first 30 specimens sent to Jefferson by Lewis in 1805 disappeared. None has been found to date although a label, written by Lewis, for plant number 26, came onto the market as a Lewis autograph in the 1970s. Its original owner is not known, and the fate of the specimens is a continuing mystery.

In late 1810, apparently in poor health, Pursh sailed for the West Indies to collect plants for the Elgin Botanic Garden. He returned nearly a year later but was probably already planning his departure for England. He arrived in London, possibly in November of 1811, and immediately fell into a period of remarkable good fortune.

Describing Flora

Pursh arrived with a large collection of plants already in hand. In addition to the small number of Lewis and Clark plants, he had retained significant portions of the plants he had gathered for both Barton and Hosack. He needed some place where he could have access to a large botanical library and collection as well as patronage. All of this he found in the home of Aylmer Bourke Lambert.

Pursh began to work immediately. In late January 1812, he wrote the president of the Linnean Society, James Edward Smith, asking if he was interested in a manuscript for the Society’s Transactions on the new species from the Lewis and Clark expedition.[8]As a young man, James Edward Smith (see http://www.linnean.org/html/history/sir_je_smith_biography.htm) (1759-1828) was traveling in Sweden when he learned that the library and collections of Carl … Continue reading

It was here that Pursh hoped to describe Lewisia (loo-WIS-ee-ah), Clarkia (CLAR-key-ah) and Calochortus (kal-oh-CORE-tus). By spring, with the encouragement of Lambert, and now with access to the libraries and collections of both Sir Joseph Banks and James Smith, Pursh was set to work on a new flora of North America.

It is said that Pursh had “tartaresque features and was correspondingly rough-hewn in behavior.” He was also reportedly an alcoholic. There is a tale, probably apocryphal, that to get the flora finished, Lambert locked Pursh in his attic room, providing him only with books, specimens, paper, ink, food and beer. A contemporary of Pursh’s described him in London as “drunk morning, noon and night,” and even Barton in Philadelphia noted that Pursh favored the “muddy ectasies of beer.” Whatever the truth, Pursh wrote away with considerable diligence. It is also obvious that Pursh was not always confined to his room. In addition to seeing the specimens owned by Lambert, Banks and Smith, he visited the University of Oxford where he consulted many early American collections such as those gathered by Mark Catesby in the 1720s.

In the spring of 1812, Pursh met Thomas Nuttall, a young man who had resided in Philadelphia from 1808 until his return to England in 1811. Like Pursh, Nuttall was hired by Benjamin Smith Barton to collect for him, basically taking Pursh’s position when Pursh went to New York. Nuttall spent much of 1810 collecting in the “Old Northwest” around the Great Lakes, but in 1811, he managed to ascend the Missouri to Lewis and Clark’s winter site of Fort Mandan, collecting dried specimens and seeds. Obviously, Nuttall recollected many of the new species Lewis and Clark had found there in 1804 and in 1806.

There now was a race by the two men to get their new genera into print.

Nuttall and Bradbury’s Contributions

Pursh abandoned his idea of publishing in the Transactions of the Linnean Society, and turned instead to the Botanical Magazine, a monthly publication designed to promote species of potential horticultural importance. In August he published Bartonia decapetala (bar-TONE-ee-ah, for Benjamin Smith Barton [deck-a-pe-TAIL-ah, having ten petals]), the gumbo-lily, or what is today known as Mentzelia decapetala (meant-ZEE-lee-ah). However, in this battle of publications, Nuttall was destined to win.[9]Pursh was not the first botanist to propose a generic name to honor Barton. In 1801, Carl Ludwig Willdenow (1765-1812) proposed Bartonia for a small genus of herbs in the gentian family. There were … Continue reading

At the same time Nuttall was meeting with Pursh in London in the spring of 1812, he was also visiting the nursery operated by John and James Fraser, the sons of John Fraser. Nuttall arranged to have his seeds raised at the Frasers’ nursery located at Sloane Square in Chelsea. The effort was highly successful, and in the early fall of 1813, Nuttall published, through the nursery, A catalogue of new and interesting plants collected in Upper Louisiana.[10]This rare publication has been the source of some debate among those interested in botanical nomenclature. First, Thomas Nuttall’s name does not appear on the printed copy; it is only found on … Continue reading In this fashion, Nuttall validly published several of the new species he found before Pursh could describe the same plant based on the collections made by Lewis and Clark and another, now nearly forgotten, botanist and Pursh’s second questionable acquisition of a collection of plants.

When Nuttall went up the Missouri River in 1811, he traveled with the American fur trader William Price Hunt, who was bound for the Columbia River on behalf of John Jacob Astor and the American Fur Company. He was also accompanied by another botanist, the English collector John Bradbury.[11]If one looks in the usual indices of botanical literature or compilations of scientific names, at least one person of note is missing, John Bradbury. His only claim to fame, and one he certainly … Continue reading

While both Nuttall and Bradbury generally followed the Missouri, Bradbury traveled overland from the Great Bend to the old Fort Mandan site, gathering many prairie species not found by Nuttall, who remained along the river. When the “Overland Astorians” finally headed westward, Bradbury returned to St. Louis, and Nuttall followed in the fall. Although the two botanists talked to one another along the river and in St. Louis, they pretty much traveled separately so that Nuttall arrived in New Orleans before Bradbury. There he was able to book passage for England, and departed. Bradbury, on the other hand, tarried and in so doing became caught up in the War of 1812 and remained in the United States. His plant collection, however, was shipped to England .

There, in a curious series of events, duplicates of Bradbury’s collection came into the possession of Lambert and thus they were seen by Pursh. Pursh then added a supplement to his Flora wherein he described most of the 40 new species found by Bradbury. Deeply offended and with his fame as a collector and discover of new plants stolen, Bradbury did little in botany after that. Nuttall, however, went on to a distinguished career, making botanical forays onto the Red River of Texas and across the continent on the Oregon Trail in the 1830s.

Pursh’s Flora

The printing of Pursh’s Flora was completed the second week of December in 1813, and on 21 December, Pursh presented copies to various of his supporters as well as submitting a copy to the Linnean Society at their monthly meeting. The formal publication as announced by the printer was 10 January 1814, but by then several copies were already effectively distributed. For botanists, therefore, Flora americae septentrionalis was published in late December 1813.

The two-volume work was a modest success. A few copies were sold with colored plates, but few buyers could afford the extra cost. In 1816 a second edition was published, but this was essentially a reprint with only minor corrections. It reception was not always kind, as several were aware of the new species others intended to publish that Pursh proposed first. The first published review did not appear until 1817. Constantine Samuel Rafinesque-Schmaltz was particularly scathing in his comment published in 1819. Twenty-five years later, Bradbury was still bitter over his experience with Pursh.

For Pursh, the decline came rapidly. He published Hortus orloviensis [HOR-tus ore-lo-vee-EN-sis] in 1815 to no particular notice, this being a catalogue of the plants found on an island near St. Petersburg, Russia. At the same time, Pursh edited the eighth edition of James Donn’s Hortus cantabrigensis (cant-a-bridge-EN-sis) without any notice of his and Nuttall’s new American plants, and while that was a commercial success, Pursh apparently received little for his efforts. A ninth edition was published within three years.

In late 1814 Pursh received two interesting proposals. One was from Lord Selkirk for Pursh to serve as botanist to the Red River settlement in Canada. The other was an invitation to establish a botanical garden at Yale University. The latter, to his probable detriment, Pursh declined. In February 1816, Pursh left England for Canada. There, in early June, he formally agreed to go to the Red River settlement in what is now Manitoba, Canada. Within two weeks, the expedition leader, Robert Semple, was murdered, and the project collapsed.

Bitter End

Bitterbrush, Purshia tridentata (Pursh) DC.

Collected on “the prarie of the knobs,” Nevada Valley,

Powell Co., Montana, 6 July 1806

Photo © 2000 James L. Reveal.

Antelope Bitterbrush

Photo © 2011 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Now in Canada, with little in the way of a livelihood, Pursh did some minor collecting, but expressed hopes of doing a flora of Canada. By 1818, with some minor support, he collected in the Gulf of St. Lawrence only to have his entire collection burn in a house fire in Montreal the following year. The year 1818 also marked the publication of Nuttall’s Genera of North American plants, which forever limited the sale of Pursh’s Flora. Drinking still and in poor health, Pursh died destitute in Montreal on 11 July 1820.

One cannot leave Pursh without commenting on his brief success. While his Flora had many flaws, they were no more serious than those found in any other work treating a large portion of the world’s flora. He has been criticized for his means of acquiring new and interesting plants and for ignoring the contributions of others, yet he was remarkably thorough for his time. He modified the Linnaean system of arranging plants into groups, making his groupings of plants much more natural than anything published to that time. He was careful to indicate whose specimens he saw and where he saw them, and where the plants grew in the wild. He annotated specimens so that today it is possible to find his comments on the herbarium sheets he examined in London and Oxford.

Pursh was a good collector, taking full and complete specimens so that one can readily identify his material today. While socially he was probably a misfit in both Philadelphia and London, he was nonetheless a gifted observer and a careful judge of what a species should be. He did what he had to do with the Lewis and Clark collection. We now know that he did not “steal” the specimens, for Muhlenberg knew he had them in his possession. Also, it must be said that the Lewis and Clark collection was not well cared for by the American Philosophical Society, whereas the specimens that Pursh retained and gave to Lambert were properly curated.

It is perhaps fitting that the western shrub that bears Pursh’s name, Purshia (per-SHE-ah), should be called bitterbrush. It is a remarkably hardy shrub wherever it occurs, and ranges widely from the deserts to the higher mountain ridges. Seemingly an awkward and often misplaced plant in the field, it is nonetheless a major food plant for grazing animals, especially deer and antelope. It may be bitter for humans to taste, but it serves its function well as Pursh served his.

References

Ewan, J. 1952. “Frederick Pursh, 1774-1820, and his botanical associates.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 96: 599-628.

Ewan, J. 1979. “Introduction to the facsimile reprint of Frederick Pursh’ Flora americae septentrionalis (1814),” p. 7-117. In: F.T. Pursh, Flora americae septentrionalis. Facsimile reprint. J. Cramer, Vaduz.

Graustein, J. E. 1967. Thomas Nuttall, naturalist. Explorations in America, 1808-1841. Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

Isley, D. 1994. One hundred and one botanists. Iowa State University Press, Ames.

McKelvey, S. D. 1955. Botanical explorations of the trans-Mississippi west, 1790-1850. Arnold Arboretum, Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts.

Moulton, G. E. (ed.). 1999. The journals of the Lewis & Clark expedition. The herbarium of the Lewis and Clark expedition. Volume 12. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln.

Nuttall, T. 1818. The genera of North American plants. 2 vols. D. Heart, Philadelphia.

Pursh, F. T. 1813. Flora americae septentrionalis. 2 vols. White, Cochrane, and Co., London.

Reveal, J.L. 1968. “On the names in Fraser’s 1813 catalogue.” Rhodora 70: 25-54.

Reveal, J. L. 1992. Gentle conquest. The botanical discovery of North America with illustrations from the Library of Congress. Starwood Publishing, Washington, D.C.

Reveal, J. L., G. E. Moulton & A. E. Schuyler. 1999. “The Lewis and Clark collection of vascular plants: Names, types and comments.” Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 149: 1-64.

Reveal, J. L. & J. S. Pringle. 1993. “Taxonomic botany and floristics,” pp. 157-192. In: Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.), Flora of North America north of Mexico. Volume 1. Oxford University Press, New York. See http://www.plantsystematics.org/reveal/pbio/usda/fnach7.html for an online version.

Rickett, H. W. 1950. “John Bradbury’s explorations in Missouri Territory.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 94: 59-89.

Related Pages

Its oak-strong, hickory-tough wood made powerful, reliable hunting bows. Early French explorers and traders translated its Indian name into bois d’arc,–”wood for a bow,” which was easily anglicized into “bodark.”

Because it appears in the Rockies at the edges of receding snowbanks it has also earned the name glacier lily. Lewis’s specimen, collected 15 June 1806 on the Clearwater River, was the one used by Pursh to describe the species.

Important for the history of the scientific accomplishments of the expedition, its first plant specimens were consigned to Barton’s care. Here began the disassembling of the collection, and his promised volume on natural history was never written.

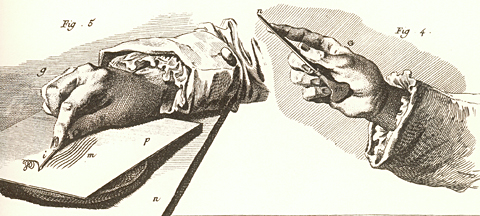

The printing of pictures employed a 350-year-old technology based on a process called intaglio—from an Italian word meaning to “cut in”—in which lines and dots were incised into a metal sheet called a plate.

Columbia plateau biscuitroots: “one of the grateful vegetables” by naturalist Jack Nisbet. An Indian food source for thousands of years.

The nomenclatural morass associated with the scientific name of Douglas-fir, Pseudotsuga menziesii, is a long and complex tale and tied closely with the early explorations along the western coast of North America . . . .

In his journal for 12 February 1806, Lewis described the plant that now goes by the name Berberis aquifolium, which he had first noticed in the vicinity of the Cascades of the Columbia River, about 145 miles from the ocean.

On 25 June 1806, on the branch of Hungery Creek where they “nooned it,” Sacagawea brought the captains “a parcel of roots” that Lewis immediately recognized as the kind Drouillard had given him ten months earlier.

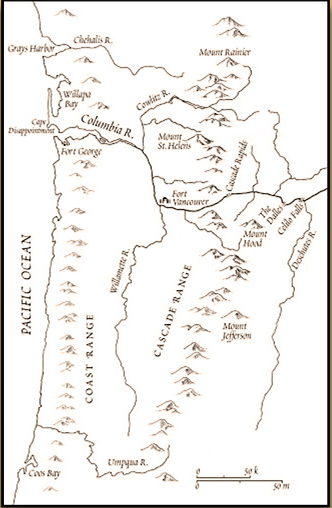

Douglas recognized landmarks from Vancouver’s and William Clark’s maps as soon as he sighted Cape Disappointment at the Columbia River’s fearsome bar. The collector continued to name familiar sentinels as he moved inland including “Mount Jefferson of Lewis and Clarke.”

Lewis’s Plant Collection

Even on the toughest days of the expedition, Lewis somehow found time to observe plants along the way. However, his major periods of systematic work evidently were at Fort Mandan, Fort Clatsop, and Long Camp.

There is a great abundance of a species of bear-grass which grows on every part of these mountains,” wrote Lewis on 15 June 1806. “It’s growth is luxouriant and continues green all winter but the horses will not eat it.”

None of the expedition’s journalists made any note of yucca, although in writing of Lemhi-Shoshone Indian dress, Meriwether Lewis mentioned “a small cord of the silk-grass” which at least one scholar has interpreted as referring to the yucca.

Flathead Salish, Kutenai, Shoshoni, and Nez Perce people all regard the bitterroot with solemn reverence. No other root may be harvested until the elder women of the tribe have conducted the annual First Roots ceremony.

Everywhere Nuttall went he found new and curious plants. Unlike most who came before him, he collected even the unattractive plants. From him, long-leaved sage and white sage, first collected by Lewis, became known to science.

William Clark, pushing on in advance of the hungry men of the Corps, came upon two adjacent Indian villages totaling about 30 lodges on Weippe Prairie. They gave him and his six hunters “roots in different States, Some round and much like an onion which they call quamash.”

Notes

| ↑1 | Nuttall named this species Virgilia grandiflora (ver-JILL-ee-ah gran-DEE-floor-ah) in his 1813 listing of plants in Fraser’s catalogue. Later in the year, Pursh proposed Gaillardia aristata (guy-YARD-ee-ah air-eh-STAY-tah, pointed or sharp). If this had been noted long ago, according to our rules of nomenclature the specific epithet, “grandiflora” should have been transferred to the genus Gaillardia. However, by the time this was discovered in 1956, there was already a species called Gaillardia grandiflora (published in 1857), so Pursh’s name is the correct name, although it was not the first name to be published for the plant. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Benjamin Smith Barton was born in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, on February 10, 1766, the son of the Reverend Thomas Barton and Ester Rittenhouse Barton. His mother was the daughter of American astronomer David Rittenhouse. Encouraged by his father, who had an interest in plants, Barton began to collect and study plants early in his life. In addition to collecting and drying plant specimens, he also studied birds and insects. The early death of his mother, in 1774, and his father’s passing in 1780, had a profound impact upon him. He was attending school at York Academy when his father died so it was not until 1782 that he went to Philadelphia to live with his older brother. The family still had considerable means so it was possible for young Benjamin to attend the University of Edinburgh, Scotland, where he obtained his medical degree. After a stay in Germany, he returned to America in 1789 and set up practice. Shortly thereafter he was appointed, at age 24, to a teaching position in natural history, and he served the University of Pennsylvania until his death on 19 December 1815. His own health was never sound and while he dreamed and planned on a grand scale, he was rarely successful. Unfortunately, the confidence placed in him by President Jefferson to work on the natural history of the Lewis and Clark expedition was misplaced. There is no question that he encouraged others to succeed and greatly furthered the career of Thomas Nuttall, among others. |

| ↑3 | No Philadelphia family is better known in botanical circles than the Bartrams. Certainly more books have been written about John Bartram (1699-1777) and William Bartram (1739-1823) than any other American botanists. William is best known for his 1791 book Travels through North and South Carolina, Georgia East & West Florida, the Cherokee Country, the extensive territories of the Muscogulges, or Creek Confederacy, and the country of the Chactaws, which bespeaks of where he collected during his active early life. A noted artist in his own right (see Botanical and zoological collections, 1756-1788 edited by Joseph Ewan and published by the American Philosophical Society in 1968), William continued his father’s nursery which remains to this day a Philadelphia landmark. See http://www.bartramsgarden.org/history/index.html |

| ↑4 | Henry Muhlenberg was born in 1753, the year the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus published Species plantarum [plan-TAR-um] and began our modern system of naming plants. Schooled in Philadelphia as a strict Lutherian, he traveled to Halle, Germany, where, from 1763 until 1770, he received his formal training for the ministry. His father, Heinrich Melchior Muhlenberg, championed Lutheranism in North America, and being a vocal American patriot, he and his family were forced to hide in the Pennsylvania forests to avoid capture during the Revolutionary War. It was here that Henry began his career as a botanist. He served the church until 1780 when he became interested in the medicinal properties of the local flora and became the local clergyman for Lancaster (in 1785). By 1791 he had gathered a few thousand specimens collected within a three-mile radius of Lancaster. His unpublished manuscript “Index flora lancastriensis” accounted for more than 450 genera and about a thousand species. His first formal publication was in 1813, when he issued Catalogus plantarum Americae septentrionalis, with a second edition appearing in 1818. In 1813, he accounted for about 1,500 species of ferns, gymnosperms and flowering plants, and over 700 species of algae, lichens, fungi and mosses. Two years after his death, Muhlenberg’s grass manuscript, Descriptio uberior graminum, was published in Philadelphia. One finds Muhlenberg’s name, abbreviated “Muhl,” associated with numerous plants in eastern North America, but with a date of publication in the early 1800s. Muhlenberg believed in sharing his knowledge and specimens with others, and thus the famed German taxonomist, Carl Ludwig Willdenow (1765-1812), working on a new, multi-volumed Species plantarum, published most of Muhlenberg’s new species at that time. The large American grass genus, Muhlenbergia (mule-en-BUR-gee-ah) was named in his honor. |

| ↑5 | Thomas Jefferson had long wished to get a naturalist to explore the vast western part of North America. A vicarious westerner, Jefferson believed if a reasonable route could be found across the continent, then trade with Asia—and in particular China—would be assured. In 1783, Jefferson approached the Revolutionary War hero George Rogers Clark with a proposal to lead an overland expedition. Clark declined. Three years later, while serving as the minister to France, Jefferson met the wanderlust Connecticut Yankee John Ledyard. Jefferson urged Ledyard to return to the United States by traveling overland from Paris to Kamchatka, cross over to Nootka Sound by ship, and then continue eastward to Virginia. Jefferson assisted Ledyard in obtaining the necessary passports, but the Russians ultimately stopped the adventurer in Siberia. A more realistic proposal was made in 1792. The French botanist, André Michaux, submitted a proposal to the American Philosophical Society for a scientific expedition to the Northwest Coast. Behind the scenes, Jefferson, at that time George Washington’s Secretary of State, had encouraged Michaux to make the proposal. An effort was then undertaken to raise £3,600 via the Society to fund the effort. The Society, at Jefferson’s urging, accepted the proposal in April of 1793, and Jefferson was soon drafting instructions. Foremost was the need to find a trade route from the upper Missouri River to the Pacific Ocean. Michaux was an excellent choice. Skilled in botany from expeditions to Persia and the Indian Ocean, as well as years of exploring in the southeastern United States, Michaux was fully capable of finding his way to the Pacific. He soon set out for the Mississippi even though he was alone and with only a pittance of financial support—$128.25, including $25 from President Washington and $12.50 each from Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton. Unfortunately, international politics were soon to interfere. In the summer of 1793, the new French minister, Edmond Genét, arrived in the United States. Genét soon asked Michaux to act as a French agent in an effort to persuade settlers west of the Appalachians to overthrow the Spanish in the Mississippi Valley, and then establish an independent nation. When Genét went so far in the fall of 1793 as to involve the United States in France’s war with Spain and Great Britain, the French minister was removed from office. Even though he was aware of Michaux’s role, Jefferson persisted in his support for the botanist through his membership in the Philosophical Society. He maintained that the need for the expedition far exceeded whatever minor role Michaux might have played in the Genét Affair. Yet, the support was not there, and in 1796 the Society abandoned the proposal and Michaux returned to France, having gotten no farther west than Kentucky. Over the next several years, Michaux labored to write a flora of North America with the aid of his son, François-André Michaux, and two notable French botanists, Louis Claude Richard, a professor of botany in Paris, and Antoine Laurent de Jussieu of the Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle also in Paris. André Michaux’s book, Flora boreali-Americana, was published shortly before his death in 1803. |

| ↑6 | Bernard M’Mahon (or McMahon, 1775-1816) was an Irish-born American horticulturalist and owner of a large commercial garden in Philadelphia. Under Jefferson’s instructions, the seeds gathered by Lewis and Clark were given to M’Mahon for cultivation and ultimate distribution. His American gardeners calendar was published in 1802. Thomas Nuttall proposed the genus Mahonia (maw-HONE-ee-ah, after M’Mahon, of course) in 1818 for two of the plants gathered by Lewis and Clark, Mahonia aquifolium (aqua-FOAL-ee-um; having leaves like a holly) and Mahonia nervosa (ner-VO-sa; alluding to the many prominent veins on the leaves). |

| ↑7 | The name of Dr. David Hosack (1769-1835) shows up in many different places in American history. Besides establishing the Elgin Botanic Garden on what is now Rockefeller Plaza in New York City, he was one of the founders of Bellevue Hospital and the New-York Historical Society, and the attending physician for the Aaron Burr and Alexander Hamilton duel in 1804. He was appointed professor of botany at Columbia in 1795, and later became the professor of materia medica at the same institution. He was an early advocate of the use a stethoscope and smallpox vaccinations. David Douglas suggested, and John Lindley published, the genus Hosackia in Edwards’s Botanical Register in 1829, an English journal devoted to new plants of potential garden interest. The genus is not accepted today, being considered a synonym of Lotus, the bird’s-foot-trefoil. |

| ↑8 | As a young man, James Edward Smith (see http://www.linnean.org/html/history/sir_je_smith_biography.htm) (1759-1828) was traveling in Sweden when he learned that the library and collections of Carl Linnaeus might be for sale. Granted the funds by his father, he made the purchase in 1784 and embarked on a career neither he nor his father ever anticipated. As a person of means, but still of consider intellect, he obtained his medical degree in 1786, and in 1788 founded the Linnean Society (see http://www.linnean.org). He served as president until his death. From this start, Smith amassed a large number of other herbaria that he brought to London and then made available to others—such as Pursh—for study. He was a prolific writer, contributing some 3,045 botanical articles and biographies for Abraham Rees’ multi-volumed Cyclopaedia published from 1802 until 1820. Smith organized Linnaeus’s collections, manuscripts, correspondence and library and again made all of it available for critical study by naturalists throughout the world. A strong promoter of the Linnaean method for classifying plants, he championed its use by publishing numerous editions of his English botany. His textbook, An introduction to physiological and systematical botany, would undergo eight English editions and one American edition, two under the editorship of other botanists after Smith died. His lavishly illustrated The English flora, begun in 1824, was completed in 1836 with William Jackson Hooker, who wrote and published the fifth and last volume. |

| ↑9 | Pursh was not the first botanist to propose a generic name to honor Barton. In 1801, Carl Ludwig Willdenow (1765-1812) proposed Bartonia for a small genus of herbs in the gentian family. There were some botanists who felt that the genus was not worthy of recognition, so in 1812 Pursh proposed Bartonia for a different genus of herbs in the loas family. Under our modern rules of nomenclature, the Pursh name was a later homonym—that is, there was an earlier use of the name. Constantin Rafinesque recognized this error and proposed Nuttallia (nuttall-EE-ah; for Thomas Nuttall) in the American Monthly Magazine and Critical Review in 1817. While most current taxonomists consider Pursh’s species to be a member of Mentzelia (described originally from specimens of a different species found in Mexico), a few recognize Nuttallia. |

| ↑10 | This rare publication has been the source of some debate among those interested in botanical nomenclature. First, Thomas Nuttall’s name does not appear on the printed copy; it is only found on the copy owned by Nuttall, and that was written in ink in his own hand. He listed numerous new species, but not all of the names were associated with descriptions—a requirement for valid publication according to the rules of botanical nomenclature. Some taxonomists in the mid-1950s questioned whether or not any of the names were correct according to the rules. The debate largely ended in 1968 when a young graduate student published a detailed review of the subject and concluded the names were valid. There is no evidence that Nuttall, in publishing his new species in 1813, was determined to discredit the efforts of Lewis and Clark, but he certainly made every effort to secure his names before Pursh described the same species using the specimens gathered by John Bradbury. |

| ↑11 | If one looks in the usual indices of botanical literature or compilations of scientific names, at least one person of note is missing, John Bradbury. His only claim to fame, and one he certainly objected to, is the long list of his 40 newly-found species described by Pursh in a last-minute supplement added to Flora americae septentrionalis. Bradbury would always feel his discoveries were “pirated” by Pursh, but this may be somewhat of an overstatement. There is no doubt Bradbury knew nothing of Pursh’s actions until well after December 1813. Bradbury was born in 1768 near Stalybridge in Lancashire and had an early interest in botany, which he sandwiched in among his duties as an employee in a cotton mill. His avocation resulted in his being elected a Fellow of the Linnean Society in 1792 at the age of 24. Living in Manchester in 1808, married and with a family, he petitioned the trustees of the Liverpool Botanic Garden for funding to visit America and collect plants. In this he was successful but not entirely as a result of his skills in natural history. His sponsors were also interested in having Bradbury work to improve the supply of cotton from America to Liverpool. Upon arriving in the United States, Bradbury met with Thomas Jefferson, who recommended that instead of setting up his base of operation in New Orleans, Bradbury should go to St. Louis. Jefferson wrote Meriwether Lewis on 16 August 1809, introducing Bradbury, little anticipating that Lewis would be dead two months later, so that when Bradbury reached St. Louis the last day of December in 1809, the letter’s recipient was in no position to render aid. During the follow year, Bradbury collected about the city, sending his dried plants and seeds to Liverpool in the late fall of the year. With the arrival of fellow Englishman Thomas Nuttall, the two took several collecting trips together. When Nuttall and Bradbury went up the Missouri River with the “Overland Astorians” in 1811, the two men were associated with different boats. Also, Manuel Lisa of the Missouri Fur Company and his men were traveling upriver as well and, having a friend with that party, Henry Marie Brackenridge, Bradbury often traveled with them. Bradbury’s specimens from the upper Missouri were sent from New Orleans in December 1811, being addressed to his son, John Leigh Bradbury. Instead of selling the collection, John gave the lot to William Roscoe of the Liverpool Botanic Garden. It was Roscoe who sent duplicates to William Jackson Hooker at the Royal Botanic Garden in Kew, Sir Joseph Banks in London, and to Aylmer Bourke Lambert. Lambert, in turn, gave the specimens to Pursh, who described the new species. Bradbury remained in the United States until 1816. In 1817 he published his Travels in the interior of America, in the years 1809, 1810, 1811. A second edition appeared in 1819 with an accompanying map of the United States. In his book he wrote that Pursh deprived him “both of the credit and profit of what was justly due to me.” Bradbury died in 1823 having accomplished nothing else in botany. Two final asides may be given. First, in April 1842 the Bradbury specimens seen by Pursh were sold by Sotheby as part of the Lambert estate. A Dr. Thomas B. Wilson purchased the lot and presented them to the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, where they may be examined today. Second, in 1817, Rafinesque proposed Bradburya (brad-BURY-ah) and in 1842, John Torrey and Asa Gray established Bradburia. Neither is used today. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.