This article is an extract from “George Rogers Clark: Jefferson’s First Emissary to the West” in the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation’s journal We Proceeded On, February 2014, Vol. 40, No. 1. The original article is provided here.

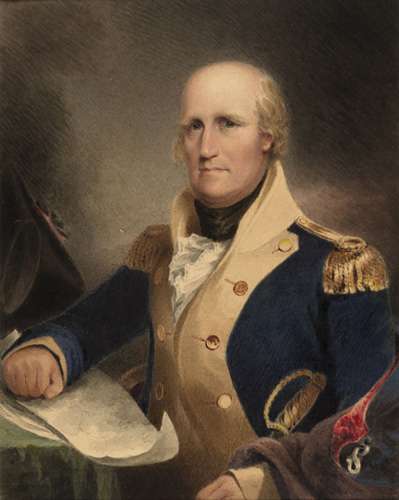

George Rogers Clark (1752–1818)

by James B. Longacre (1794–1869)

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, https://npg.si.edu/object/npg_NPG.72.14.

James Longacre made this copy from the c. 1820 John Jarvis portrait commissioned by William Clark. Jarvis based his portrait on descriptions and family resemblances. No image made during Clark’s prime years is known to exist.

Introduction

If you had quizzed people as late 1930 about the contributions of the Clark family to American history, William was not the Clark most people would have mentioned. At that time, William’s older brother George was by far the most famous member of the family. In the late nineteenth century, the American conquest of the land between the Appalachians and the Mississippi was considered one of the central stories of the American Revolution. George Rogers Clark was called “The Hannibal of the West,” and was compared to George Washington. Statues to him were erected, novels were written, and a national monument was built in Vincennes, Indiana, and dedicated by Franklin Roosevelt. Then, after the 1930s, George fell out of fashion. Now his fame is eclipsed by his younger brother’s.

There are reasons why historians have been reluctant to touch George Rogers Clark in the last forty years. He is a more difficult person to explain than William was, and harder to like. In the 1970s, historians portrayed him—with much truth—as an anti-Indian racist and an advocate of genocide. That he became embroiled in the plot of Citizen Genet and ended up destroying himself with alcohol and bitterness were exhibited as proof of his unworthiness to be called a hero.

But dismissing George Rogers Clark as a sociopath or alcoholic is too easy. It is far more interesting to attempt to understand him. Viewed as a whole, George was a complex man who was deeply scarred by warfare. He is a tragic figure, but his was a particularly American kind of tragedy. He was, above all, a man of the Middle Ground—the blended society that existed on the frontier before the Revolution. The term “Middle Ground,” coined by historian Richard White in his 1991 book of the same name, is often misunderstood to mean a frontier where Indians, French, Anglos, Africans, and other inhabitants all got along in some kind of idyllic multicultural mix. That was never true. In fact, much of the intercultural interaction in the West of that era took the form of warfare. But war is a kind of communication, too. European and Indian customs of warfare were very different, and Clark stood right on the boundary. In his most successful moments he crossed over and acted as an Indian war chief: he used their tactics, employed their methods to create group cohesion, shared their sense of honor and justice, terrorized his opponents into believing in his savagery, and even committed what Europeans regarded as atrocities. At the same time, he could put on a uniform and transform himself into a Virginia gentleman.

His tragedy was that his own success led to the destruction of the mixed society that created him. The America that came to exist in the Kentucky he defended was an alien society where he could not thrive. No man was more skilled at spanning the difficult boundary between warrior and soldier, but when that boundary ceased to exist, so did his vocation.[1]I expand on Clark’s career at some length in my book, Land of the Blended Heart: The American Revolution on the Frontier (forthcoming), on which this paper is based. For the Middle Ground, see … Continue reading

And so Clark was a hero in the Greek sense: a man of genius whose own talents and flaws inevitably destroy him.

So Much Like Lewis

To readers familiar with the story of Lewis and Clark, there is another striking thing about the life of George Rogers Clark: the eerie similarity between his story and that of Meriwether Lewis. Focusing on those similarities, one finds a common thread running through both of their lives: the role of Thomas Jefferson.

Jefferson admired both Clark and Lewis as men of action and frontiersmen. He used both of them as instruments to expand the United States westward. After they had accomplished extraordinary feats for him, he thrust them both into treacherous political positions where their skills did not translate well. He encouraged both of them to incur heavy expenses in accomplishing his pet projects, and both of them ended up deep in debt and under investigation by a subsequent administration. Facing financial ruin, both of them turned to alcohol and self-destruction. And in both cases, Jefferson seems to have been strangely oblivious of his role in their fates. It is hard not to conclude that Thomas Jefferson left a trail of collateral damage in the form of ruined lives along the road to his empire of liberty.

George Rogers Clark, like Meriwether Lewis, was born in Albemarle County, Virginia, a few miles away from Shadwell, Jefferson’s boyhood home. The Clark family soon moved away, however, and Jefferson and Clark did not meet as adults until 1776. In August of that year, the red-haired, charismatic young Clark knocked on the door of Patrick Henry, then governor of Virginia, and presented him with a document and a dramatic story. The document was a petition from the residents of Kentucky, and it declared:

The Inhabitants of this Frontier part of Virginia . . . support . . . the present laudable cause of American Freedom, and . . . most ardently desire to be looked upon as a part of this Colony And as those very People would most Cheerfully Cooperate in every measure tending to the Publick Peace, and American Freedom, they have delegated two Gentlemen, who was chosen by the Free Voice of the people . . . as our Representatives.[2]Kathrine Wagner Seineke, The George Rogers Clark Adventure in the Illinois (New Orleans: Polyanthos, 1981), 181-82.

The two men elected, George Rogers Clark and John Gabriel Jones, had walked through drenching rain all the way from Kentucky down the Wilderness Trail to the Cumberland Gap.

This portrait shows Thomas Jefferson as he would have appeared in 1776. It was one of three Trumball made from his earlier painting of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. It was given by Maria Cosway to the school she had founded in Italy. It was later gifted to the White House “as a gift to the American People.”[3]WikiCommons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Thomas_Jefferson_by_John_Trumbull_1788.jpg; “Thomas Jefferson by John Trumbull,” The White House Historical Association, … Continue reading

Two Western Visions

When most Americans looked west, they imagined the past repeated on a new stage. The Atlantic seaboard had not been populated by disorganized hordes, or by a government-run public-works project. America’s orderly development had been privatized, contracted out to wealthy individuals or companies that were granted control over particular regions by the Crown. They provided incentives for migrants and controls that kept society from breaking down: a governor, courts, land offices to register deeds, sheriffs to keep order, in some cases a clergy. In 1776 a variety of companies had sprung up to serve the same role beyond the Appalachians. They were like developers of subdivisions today, only on a grand scale. They expected to make money doing it.

When Jefferson looked west, he imagined something radically new happening. He didn’t project the past onto the West, but the future. He imagined that people would move west individually, on their own initiative, and civil society would spontaneously spring up among them without any intervention from outside authorities. Self-rule was the natural state of society, or so Locke maintained. It might be necessary for established democracies like Virginia to protect the fledgling. democracies for a time, but they would eventually mature, stand up on their own, and break free. In fact, Jefferson wrote in his notes for the Virginia constitution that they should become “free and independent of this colony and of all the world.”[4]Thomas Jefferson, The Papers of Thomas Jefferson (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1950–ongoing), 1:363.

As a member of the Continental Congress in 1776, Jefferson had seen lobbyists from several land companies approach Congress for confirmation of their titles to western lands. Their techniques of lobbying left him deeply suspicious that they were sources of corruption threatening the republican virtue of Congress. Jefferson read the bylaws of one company, called the Transylvania Company, and he saw vestiges of feudal bondage in the quitrents settlers would pay and the executive authority of the unelected proprietors. The private companies came to represent for him the European system of subservience replicated once more beyond the mountains.[5]Anthony Marc Lewis, “Jefferson and Virginia’s Pioneers, 1774- 1781,” Mississippi Valley Historical Review, 34(4) (March 1948).

George Rogers Clark had come to Williamsburg in 1776 because of opposition to that same Transylvania Company made up of a group of North Carolina investors headed by Judge Richard Henderson. The company had purchased a tract of land in Kentucky from the Cherokee Indians, and hired Daniel Boone to guide a party of migrants over the mountains. Once there, they founded the town of Boonesborough and set up a land office to sell off tracts. But they soon alienated the other inhabitants of Kentucky by raising land prices and insisting that people actually settle on their land and plant corn, instead of flipping the property to new buyers in the East. So Clark and the young firebrand lawyer John Gabriel (“Jack”) Jones organized an opposition. It was a stroke of political genius for them to couch their protest in revolutionary terms that echoed the Declaration of Independence being written almost simultaneously in Philadelphia.[6]Stephen Aron, How the West Was Lost: The Transformation of Kentucky from Daniel Boone to Henry Clay (Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996), 61-64; on Jones, see Neal Hammon … Continue reading

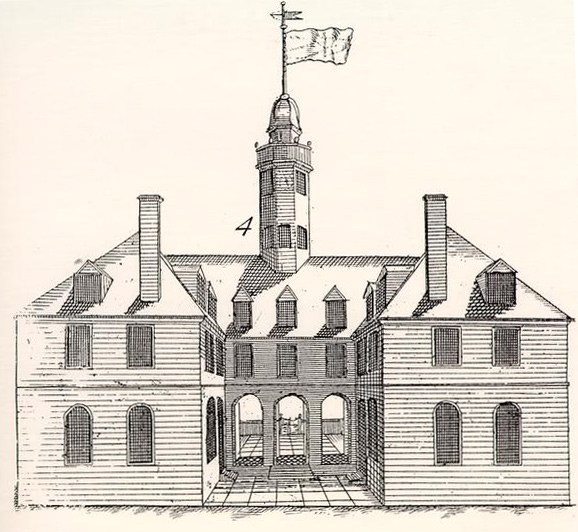

Capitol of Virginia

Possibly by John Carwitham or Eleazar Albi

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Gift of the Bodlean Library.

This engraving, from about 1740, depicts the capitol building in which Clark presented his case to the Virginia Assembly.

Creating Kentucky County

Jefferson, Clark, and generations of historians framed the ensuing battle as a principled conflict between the model of developing the West for the private gain of wealthy investors, and the model of developing the West as a land of small freeholders who owed no allegiance to aristocrat landlords. Only recently have we realized it was something slightly different: a struggle of small-scale speculators against large-scale speculators.

The showdown came in the Virginia Assembly session of October 1776. Richard Henderson showed up to argue his case, supported by Tidewater aristocrats who themselves had investments in western land companies. They framed it as a case of unwarranted government interference against private enterprise. After all, the Transylvania investors were not doing anything illegal or immoral. In their own eyes, they were providing a useful public service, by helping to promote orderly settlement of the West as opposed to a chaotic, uncontrolled free-for-all. If they made money, what was un-American about that? And what gave the state of Virginia the right to step in and tell them to stop?[7]Jefferson, Papers, 1:566; Robert L. Scribner and Brent Tarter, eds., Revolutionary Virginia: The Road to Independence, vol. 7, pt. 2 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1983), 508-10.

But Jefferson rallied the western delegates, and Clark hinted darkly that Transylvania would “afford a safe Assylum to those whose Principles are inimical to American Liberty.” To avoid the nightmare scenario of harboring a Tory enclave at their backs, the Assembly created Kentucky County, Virginia. By asserting the sovereignty of the state of Virginia beyond the mountains, they effectively quashed the colony of Transylvania.[8]Seineke, George Rogers Clark Adventure, 182.

Morgan’s Military Expedition

The next time Clark and Jefferson teamed up was exactly one year later. This time the threat to democracy was no longer aimed at Kentucky, but farther west, at Illinois.

Illinois at this date defied our popular stereotype of the West as a trackless wilderness. In fact, after crossing the Appalachian Mountains in 1777, the land became more settled and more European the farther west you went. When you reached the Mississippi River, you would have found yourself in a place resembling a little piece of rural France transported to America. The first French towns there were founded around 1700. Almost eight decades later the river bottom for about one hundred miles north of the Kaskaskia River was almost continuous farmland, pasture, and orchard. There were roads, churches, and mills. The people there prospered by exporting farm produce, mining lead, and conducting commerce with the Indians. The west side of the Mississippi was claimed by Spain and the east side was nominally under British control, but there were no British soldiers there—only a single harried bureaucrat named Philippe Rocheblave, who had received neither money nor orders from Britain for about two years.[9]Carl J. Ekberg, French Roots in the Illinois Country: The Mississippi Frontier in Colonial Times (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1998); for Rocheblave, see Paul L. Stevens, … Continue reading

In summer of 1777, the Continental Congress approved funding for a military expedition to descend the Ohio River and seize control of Illinois, then continue on down the Mississippi to attack the British forts at Mobile and Pensacola. It was not to be commanded by George Rogers Clark. The mastermind behind the plan was a Pennsylvanian named George Morgan. He was the United States’ Indian agent in the West, but also a land company investor. He had been part of a group that proposed a colony in Illinois in the 1760s, and he was now fighting a very public battle with Virginia over a different colony, named Indiana. His main opponents in Virginia were George Mason and Thomas Jefferson.[10]Here and below, see Carolyn Gilman, “Why Did George Rogers Clark Attack Illinois?” Ohio Valley History, 12(4) (Winter 2012).

When the Virginians heard of the military expedition Morgan had gotten through Congress, they became alarmed. Illinois lay within the boundaries of Virginia’s original royal land grant, and if the Continental Army were to seize it, as planned, Virginia would lose any claim to it. They probably feared, with good reason, that this would open the door to Pennsylvanian land companies like Morgan’s. If Virginia wanted to defend its western lands and people, it would have to do something decisive.

At this moment, George Rogers Clark showed up in Williamsburg. He was already exhausted by war. That summer of 1777, Britain had changed its longstanding policy of trying to persuade the western Indian tribes to stay neutral, and had started actively arming them and encouraging them to create a diversion along the western borders of the United States. The result was a summer of incessant war, in which settlers were driven back, towns abandoned, and both Boonesborough and Harrodsburg reduced to armed forts. As major of the Kentucky County militia, Clark had spent the summer directing the defenses. He said, “The defence of our Forts the procuring of provitions and when possible supprising the Indeans . . . burying the dead and dresing the wounded seemed to be all our business.”[11]James Alton James, ed., George Rogers Clark Papers 1771-1781, Illinois State Historical Library, Collections, v. 8—Virginia Series, vol. 3 (Springfield: Illinois State Historical Library, 1912), … Continue reading

George Rogers Clark

National Historic Park

Original photo by Jud McCranie, WikiCommons. The original here has been altered to remove a tourist from the lower-right corner. Permission granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

In the George Rogers Clark Memorial, seven murals depicting his acts surround his statue. An engraving above the murals says: “Great things have been effected by a few men well conducted,” and the inscription on the statue’s base reads: “If a country is not worth protecting it is not worth claiming.” The oil on canvas murals stand 28 feet tall and 16 feet long and took artist Ezra Winter and his six assistants two years to complete.[12]“Inside the George Rogers Clark Memorial,” George Rogers Clark National Historical Park, National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/gero/learn/historyculture/inside.htm accessed 14 September 2022.

The National Park Service describes Clark’s accomplishments with pages about each event depicted on the murals:

“Vive la liberté!”

Together, Clark, Jefferson, and Mason came up with a plan to save Illinois. They used a ploy Jefferson would rely on again when he wanted to get money out of Congress for a pet project: they introduced a vaguely worded bill to the Virginia Assembly, authorizing an expedition to the West, but lowballing the cost and neglecting to state the true purpose. It worked, just as it would in 1803. With an appropriation in the works, Clark then went to Governor Patrick Henry with an implausible argument that Illinois constituted a threat to Kentucky. Henry was skeptical, but after some persuasion he authorized Clark to seize the Mississippi River for Virginia before the Pennsylvanians could get there.

Clark set off from Pittsburgh with a band of about 175 adventurers to conquer Kaskaskia, a town of about 1,500 inhabitants. The story of how they managed to bamboozle the French residents into joining them is a classic tale. According to Clark, he did it by putting on his Indian persona until he had thoroughly terrorized the town, then suddenly switched to his Virginia gentleman persona. The French habitants were so relieved to find they weren’t going to get plundered and massacred that they embraced the American cause and cried, “Vive la liberté!”

Victory at Vincennes

Once he had occupied the towns of French Illinois, Clark was faced with a dilemma: what was he supposed to do with them? He didn’t have the men, money, or orders to rule or defend them, but he also didn’t want to retreat. He wrote to Virginia for instructions, and in the meantime he borrowed money to feed, clothe, and house his men, and to carry on diplomacy with the Indian tribes.

All his plans were disrupted that fall when Henry Hamilton, the British lieutenant governor of Detroit, mounted an expedition to retake Illinois. The British only got as far as Vincennes before winter set in, but that was far enough to cut off Clark. Now there was no retreat for the Americans; either they had to flee across the Mississippi River into Spanish territory, or attack. Clark chose to attack.

The story of Clark’s midwinter march to Vincennes is one of the best war stories of all time. It has been told so often there is no need to repeat it here. Unbelievably, considering all he was up against, Clark was able to retake Vincennes without losing a single man. He captured Hamilton and all his officers, inflicting a humiliating defeat on Britain.

By the time the news of Clark’s victory at Vincennes arrived in Virginia, Thomas Jefferson had been elected to replace Patrick Henry as governor, and he had the pleasant task of taking credit for the victory. For the next two years, Jefferson and Clark entered into a close partnership—Jefferson as governor, Clark as his man in the West.

Feeding Jefferson’s Western Vision

To Jefferson, the West was a grand scientific experiment in the cultivation of humankind. This explains the urgency with which he defended the West in the Revolution. It was not just the future of Virginia riding on the outcome; it was the future of the United States, of democracy, of mankind. The West was, as he wrote Joseph Priestly, a “new . . . chapter in the history of man.”[12]Peter Onuf, Jefferson’s Empire: The Language of American Nationhood (Charlottesville and London: University Press of Virginia, 2000), 1.

Clark fed the flames of Jefferson’s enthusiasm for the West by sending back descriptions much like Meriwether Lewis would write twenty-five years later: “Its more Beautiful than any Idea I could have formed of a Country almost in a state of Nature. . . . On the River You’ll find the finest Lands the Sun ever shone on; In the high Country You will find . . . large Meadows extending beyond the reach of your Eyes Varigated with groves of Trees appearing like Islands in the Seas covered with Buffaloes and other Game; in many Places with a good Glass You may see . . . half a Million of Acres.”[13]James, ed., Clark Papers, 154.

There were two critical components of Jefferson’s plan for the West. One was to establish a Virginia-style democracy in Illinois in order to “inculcate on the people the value of liberty, and the difference between the State of free Citizens of this commonwealth and the Slavery to which Illinois was destined.” The second cornerstone of his program was the establishment of a fort on the banks of the Mississippi, the westernmost boundary of the United States. It was not just meant to protect Illinois; it would declare to both Britain and Spain that the United States was in the West to stay. It would be called Fort Jefferson.[14]James, ed., Clark Papers, 85.

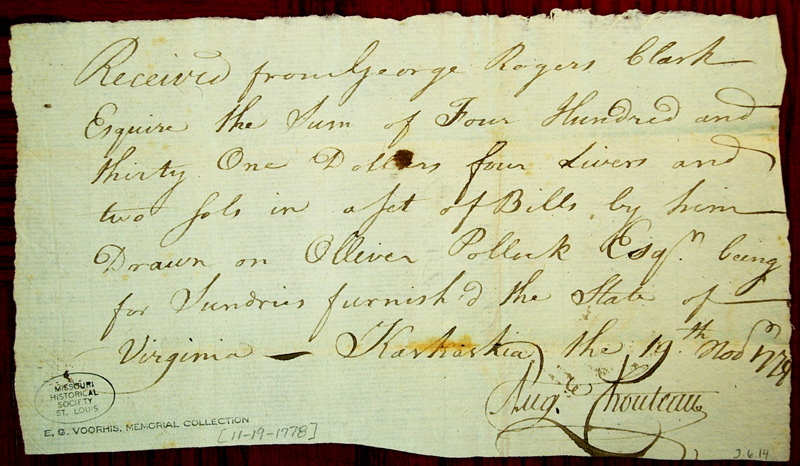

Receipt to George Rogers Clark (1778)

Missouri Historical Society, https://mohistory.org/collections/item/A0289-00022.

Promissory note from George Rogers Clark to Auguste Chouteau. This IOU is one of dozens to French merchants who sold Clark supplies on credit. William Clark used it in his later effort to straighten out his brother’s finances.

Building the Western Army

Jefferson put in Clark’s hands the creation of an entire military infrastructure to defend the West. Starting with nothing but a handful of half-literate frontiersmen, Clark was asked to whip together all the administrative structure of an army: quartermasters, commissaries, artificers, officers, and even washerwomen to keep the men uniformed, armed, disciplined, and fed. At its height the Illinois battalion manned five forts spread over a three-hundred-mile radius, with headquarters at Louisville. But defending an empire isn’t cheap, and there wasn’t a shilling in the Virginia state treasury to pay for it all. Virginia had been financing its eastern war by printing paper money, and its economic house of cards had collapsed in the midst of 16,000% inflation. By 1780 the state’s credit was worthless, and Clark’s entire western department was built on credit.[15]Here and below summarizes a story told in more detail in Gilman, Land of the Blended Heart.

Jefferson was in denial. He wrote Clark minute instructions about the construction of Fort Jefferson as if money were no object, just as he would later write Meriwether Lewis an unsupported letter of credit. Clark improvised madly to find ways of accomplishing what Jefferson wanted. In the Clark papers at the Missouri History Museum are stacks and stacks of IOUs he wrote in hopes that Jefferson would cover them all; leafing through them, you get a sense of looming disaster. During the year of 1780, Clark built Fort Jefferson and fought back two British counterstrikes, one aimed at Illinois and the other at the heart of Kentucky. Two of the battles that year were the largest of the war in the West, each involving over a thousand men. Between May and September he was barely in the same place for more than two weeks at a time, but he still set off for Virginia to confer with Jefferson over the winter.

When Clark arrived in Richmond, he found that Jefferson had no more men or money than before, but was still cooking up another project for him. Jefferson wanted to attack Detroit, the headquarters of British operations in the West, and he had already been writing letters to get George Washington’s cooperation. Clark wanted to attack Detroit, too, but he must have been a little wary of Jefferson’s promises by now, because he had some conditions. He wanted a promotion and a guarantee of two thousand men to command. Jefferson agreed, and sat down on Christmas Day, 1780, to write him a set of detailed instructions, outlining the objectives of the expedition, just as he would later do for Lewis. Clark set out soon after. But in the end, Jefferson was not able to produce either a permanent promotion or the two thousand men. Clark spent all spring fruitlessly trying to recruit men around Pittsburgh, and finally set out with a force of only 350. When he reached Louisville he received the news: Jefferson had been voted out of office, and the Virginia Assembly had passed a bill calling for the new governor to cancel the Detroit expedition. They had also appointed a commission to investigate the finances of Clark’s Western Department.

Clark’s last year in command of the western war, 1782, was dominated by divisiveness. The new governor of Virginia was Benjamin Harrison, a signer of the Declaration of Independence and father of William Henry Harrison. He was supportive at first. Under his instructions, Clark built a fleet of gunboats to patrol the Ohio River; the largest one was seventy-three feet long at the keel, propelled by forty oars, and had “false gunwales” that could be raised on hinges to form a shield in case of attack—a design later used by Lewis on his keelboat. But in August, the Kentucky militia suffered a devastating defeat when they impetuously charged into an Indian ambush at Blue Licks. In the coverup that followed, Clark became the scapegoat for not having been there to prevent the disaster. In 1780, Clark had been the idol of Kentucky. By 1782, they were accusing him of incompetence, corruption, and alcoholism. Harrison, who had never met Clark, believed the worst. The next spring he wrote Clark, “The conclusion of the war . . . will render the Services of a General Officer in [the West] unnecessary, and [you] will therefore consider yourself as out of Command.”[16]For the gunboat design, see James, Clark Papers, Illinois State Historical Library, Collections, v. 19—Virginia Series, v. 4 (Springfield: Illinois State Historical Library, 1926), 64, 137; for the … Continue reading

It was the end of Clark’s military career. He was thirty years old, out of a job, and on the brink of financial ruin. He had gone far out on a limb to make Jefferson’s dream a reality in the West, and now his countrymen sawed off the branch behind him. He had never been defeated in battle; what defeated him was an inability to make the transition from a military leader to a politician.

George Rogers Clark

By Hermon Atkins MacNeil

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HMcNeil-GRClark.jpg>. Permission via the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Hermon Atkins MacNeil’s list of works include the Standing Liberty Quarter minted between 1916 and 1930, Civil War Soldier’s Monument (Philadelphia, 1921), “Coming of the White Man / Chief Multnomah “, Jacques Marquette bas-reliefs (Chicago, 1894), and the Pony Express Monument (St. Joseph, 1940).[17]“Hermon Atkins MacNeil,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hermon_Atkins_MacNeil accessed on 9 February 2021.

Tragic Greek Heroes

Astonishingly, George Rogers Clark never blamed Thomas Jefferson. In fact, when George learned that William was being considered for another wild Jeffersonian scheme to explore the West, he expressed encouragement. But he was a ruined man. Unable to live up to Jefferson’s impossible expectations, he turned to self-destruction by alcohol, and by 1803 he was like the ghost of a former time.

It is easy to see similarities between Jefferson’s two emissaries to the West, George Rogers Clark and Meriwether Lewis. But there was one important difference: Lewis knew Clark’s story. In 1809, when he found himself in a similar situation—under political attack, under government investigation, all his heroism forgotten—he had the spectre of George Rogers Clark hanging before him, and the thought that he might end up the same way. It may give us an insight into what was going through his mind in those dark days.

In Greek tragedy, a hero is a person who embodies his nation or people. He need not be perfect; on the contrary, he is often a flawed mix of human and divine. By this measure, George Rogers Clark qualifies as a hero. He embodied the paradoxes of a nation struggling toward a great moral vision through compromise with an imperfect world of people. The question he poses to us is: are we going to fall prey to our flaws, or are we going to transcend them to keep this project of democracy going? It is still our great national challenge, just as it was in his time.

Related Pages

- George Rogers Clark -

Jefferson put in George Clark's hands the creation of an entire military infrastructure to defend the West. Clark was asked to whip together all the administrative structure of an army: quartermasters, commissaries, artificers, officers, and even washerwomen to keep the men uniformed, armed, disciplined, and fed.

- September 3, 1803 -

Industry, PA Morning fogs delay departure. Lewis is encouraged when men in two boats loaded with furs tell him the Ohio becomes deeper twenty-four miles downriver. The barge must be unloaded and dragged by horses. They eventually pass Fort McIntosh.

- October 17, 1803 -

Falls of the Ohio, KY-IN Clark and Lewis visit fellow traveler Thomas Rodney sharing wine on his bateaux moored at Bear Grass Creek. In Washington City, Thomas Jefferson gives his third Annual Message to Congress.

- Fort Massac -

Six years before signing on with the Lewis and Clark Expedition, George Drouillard took part in a sensitive international mission for the United States Army. This mission was probably just one of Drouillard's many services to the United States in the last decade of the eighteenth century.

- The Mouth of the Ohio -

On the evening of 14 November 1803, Lewis and Clark camped on the point between the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. By now they had rowed, poled, dragged, and occasionally sailed their boats a total of 981 miles.

- November 18, 1803 -

Mouth of the Ohio, IL The captains and eight men cross the Ohio to visit Fort Jefferson, started by William's older brother, George Rogers Clark. Near Natchez, the Governor of the Mississippi Territory notices that Spanish officers are reluctant to cede Louisiana to France.

- November 23, 1803 -

Old Cape Girardeau, MO Lewis brings letters of introduction to Louis Lorimier, whose store was burned to the ground by George Rogers Clark in 1782. Pryor still hasn't returned from a hunting trip, and Clark's illness continues.

Notes

| ↑1 | I expand on Clark’s career at some length in my book, Land of the Blended Heart: The American Revolution on the Frontier (forthcoming), on which this paper is based. For the Middle Ground, see Richard White, The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650-1815 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Kathrine Wagner Seineke, The George Rogers Clark Adventure in the Illinois (New Orleans: Polyanthos, 1981), 181-82. |

| ↑3 | WikiCommons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Thomas_Jefferson_by_John_Trumbull_1788.jpg; “Thomas Jefferson by John Trumbull,” The White House Historical Association, https://www.whitehousehistory.org/photos/thomas-jefferson-by-john-trumbull both accessed 14 September 2022. |

| ↑4 | Thomas Jefferson, The Papers of Thomas Jefferson (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1950–ongoing), 1:363. |

| ↑5 | Anthony Marc Lewis, “Jefferson and Virginia’s Pioneers, 1774- 1781,” Mississippi Valley Historical Review, 34(4) (March 1948). |

| ↑6 | Stephen Aron, How the West Was Lost: The Transformation of Kentucky from Daniel Boone to Henry Clay (Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996), 61-64; on Jones, see Neal Hammon and James Russell Harris, eds., “‘In a dangerous situation’: Letters of Col. John Floyd, 1774–1783,” Register of the Kentucky Historical Society, 83(3) (Summer 1985), 203, 214; Neal O. Hammon, “Land Acquisition on the Kentucky Frontier,” Register of the Kentucky Historical Society, 78(4) (Autumn 1980), 308. |

| ↑7 | Jefferson, Papers, 1:566; Robert L. Scribner and Brent Tarter, eds., Revolutionary Virginia: The Road to Independence, vol. 7, pt. 2 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1983), 508-10. |

| ↑8 | Seineke, George Rogers Clark Adventure, 182. |

| ↑9 | Carl J. Ekberg, French Roots in the Illinois Country: The Mississippi Frontier in Colonial Times (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1998); for Rocheblave, see Paul L. Stevens, “‘To Invade the Frontiers of Kentucky’? The Indian Diplomacy of Philippe de Rocheblave, Britain’s Acting Commandant at Kaskaskia, 1776-1778,” The Filson Club History Quarterly, 64(2) (April 1990), 205-46. |

| ↑10 | Here and below, see Carolyn Gilman, “Why Did George Rogers Clark Attack Illinois?” Ohio Valley History, 12(4) (Winter 2012). |

| ↑11 | James Alton James, ed., George Rogers Clark Papers 1771-1781, Illinois State Historical Library, Collections, v. 8—Virginia Series, vol. 3 (Springfield: Illinois State Historical Library, 1912), 217-18. |

| ↑12 | Peter Onuf, Jefferson’s Empire: The Language of American Nationhood (Charlottesville and London: University Press of Virginia, 2000), 1. |

| ↑13 | James, ed., Clark Papers, 154. |

| ↑14 | James, ed., Clark Papers, 85. |

| ↑15 | Here and below summarizes a story told in more detail in Gilman, Land of the Blended Heart. |

| ↑16 | For the gunboat design, see James, Clark Papers, Illinois State Historical Library, Collections, v. 19—Virginia Series, v. 4 (Springfield: Illinois State Historical Library, 1926), 64, 137; for the quote, 245. |

| ↑17 | “Hermon Atkins MacNeil,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hermon_Atkins_MacNeil accessed on 9 February 2021. |