As lasting mementos of the

Lewis and Clark Expedition,

seven Osage orange trees in the

churchyard of St. Peter’s comprise

Philadelphia’s living counterpart

to Clark’s name on Pompeys Pillar

beside the Yellowstone River.

Wood for Bows

Here is a view of one of the Osage orange trees, including its fruit, that have been growing in the churchyard at St. Peter’s Episcopal Church in Philadelphia for more than 200 years. It is believed that they were grown from the slips that Lewis sent to Jefferson, who forwarded them to Bernard McMahon of Philadelphia. It is certain that McMahon, who history remembers as “America’s pioneer nurseryman,” planted some in front of his store on Fourth Street, opposite the church.[1]Donald Jackson, Thomas Jefferson & the Stony Mountains: Exploring the West from Monticello, Reprint, with a foreword by James P. Ronda (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1993), 161 n.52.

The Osage orange tree can thrive in any kind of soil, rich or poor, wet or dry. In the purposely crowded environment of a cultivated and well-groomed hedgerow, it is shrubby. Without competition, however, and in soil that provides sufficient nutrients, as in the churchyard of St. Peter’s, it may reach a height of 50 feet or more–as this one does–with a crown spread of up to 60 feet.

Indian peoples knew and valued this tree for its primary utility in their lifeways: its oak-strong, hickory-tough wood made powerful, reliable hunting bows. Early French explorers and traders translated its Indian name into bois d’arc,–”wood for a bow,” which was easily anglicized into “bodark.” Lewis was told, he wrote to Jefferson, “so much do the savages esteem the wood of this tree for the purpose of making their bows, that they travel many hundred miles in quest of it.” That quest could be protracted exponentially by the time and effort needed to find a straight-grained, knot-free part of a trunk long enough to make a few useful weapons. Indigenous to the Arkansas River bottoms that are now in parts of Arkansas, Oklahoma, and northern Texas, it was prized not only by The Osages but also by the Comanches, Kiowas, Pawnees, Omahas, Seminoles, and many others. The Scottish naturalist John Bradbury (1768-1823), who studied American flora along the Missouri in 1810, found bows as well as war clubs made of bois d’arc among the Arikaras.[2]The design that Bradbury described resembled the “war hatchet” Clark sketched in his journal on 28 January 1804. In the early 1830s, the peripatetic Prince Maximilian of Wied-Neuwied saw one growing on the grounds of the utopian village of New Harmony in Indiana.[3]Maximilian Prince of Wied’s Travels in the Interior of North America, during the years 1832–1834. In: Reuben Gold Thwaites, ed., Early Western Travels, 1748-1848, 1906, (vol. 22-25), 189.

From Lewis’s Slips

The fruit of the Osage orange tree, which grows only on females of the species, is a syncarp–a stringy, fleshy compound that develops from a cluster of several of greenish watery-pale flowers. Each tiny green bump–200 or more per syncarp–is the outer end of an achene (ay-keen) anchored deep in the pulpy core, and holding a single orange-colored seed. The black hairs seen in the photo are styles, each of which connected a stigma to an ovary.

Lewis described its makeup, presumably from Chouteau’s account: “The pulp is contained in a number of conacal pustules [achenes], covered with a smooth membranous rind, having their smaller extremities attached to the matrix, from which, they project in every direction, in such manner, as to form a compact figure. the form and consistancy of the matrix and germ, I have not been able to learn. The trees which are in the possession of Mr. Choteau have as yet produced neither flowers nor fruit.”

The ripe fruit contains a chemical (2, 3, 4, 5-tetrahy-droxystilbene) that repels many insects.

Who could have imagined that a shrub so unruly or a tree so graceless, with a fruit so bitter, thorns so brutal, a wood so hard and propagation so undisciplined, could earn so admirable a reputation in American Indian culture for hundreds of years? Who could have predicted it would become a major instrument in the opening of the West–or rather, the enclosing of the prairies? By all standards one of the least attractive trees in the forest, how did it come to have its image ennobled by association with a few famous men?

Meriwether Lewis wrote to Thomas Jefferson from St. Louis on 26 March 1804, a few weeks before embarking on the expedition. “I send you herewith inclosed, some slips of the Osages Plums, and Apples. I fear the season is too far advanced for their success.” He had obtained the cuttings “from the garden of Mr. Peter Choteau, who resided the greater portion of his time for many years with the Osage nation.”[4]Pierre Chouteau (1758-1849) and his older brother Auguste (1749-1829) were the leading entrepreneurs in St. Louis and Upper Louisiana at the turn of the 19th century. They were especially influential … Continue reading Pierre Chouteau, who had introduced the species to gardens in and around the village of St. Louis at the end of the 1790s, told Lewis he got them “at the great Osage vilage from an Indian of that nation, who said he procured them about three hundred miles west of that place.”[5]Jackson, Letters, 1:170-71. Clark’s description of the “great Osage vilage,” situated on the upper Osage River and the Arkansas River, is the first item in his “List of the … Continue reading

According to Chouteau they were Osage apple trees; later travelers called them Osage orange, evidently because of the appearance of their fruit from a distance. Close up, however, the likeness disappears, and biologically they’re nowise related to real apples or oranges. They aren’t even edible, although rumor has it that they are palatable to blacktailed deer, fox squirrels, and hares. “An opinion prevails among the Osages, that the fruit is poisonous,” Lewis related, “tho’ they acknowledge that they have never tasted it.” Furthermore, an ancient cultural memory may have reminded them that its sap is notoriously bitter, sticky to the touch, and can cause severe dermatitis.

Having seen only a few five-year-old saplings, and therefore relying solely upon Chouteau for most details, Lewis explained to Jefferson that the fruit was “the size of the largest orange, of a globular form, and a fine orange colour.” A grapefruit makes a better comparison as far as size–up to about six inches in diameter–and weight are concerned. For some reason, perhaps their more northerly latitude, the fruits of the Osage orange trees in Philadelphia can barely boast a tinge of pale greenish-yellow when ripe. Lewis also reported that the Indians “give an extravigant account of the exquisite odour of this fruit when it has obtained maturity, which takes place the latter end of summer, or the begining of Autumn.” The fragrance of its Philadelphia relations is reportedly much more delicate than that of a citrus orange (Citrus sinensis).

Setting aside the analogy of the familiar citrus fruit, the tree shows ample evidence of the corresponding color. Patches in the gray outer bark are tinged with pastel orange; the thin sapwood is light orange; and the heartwood is yellow when first cut, darkening to deep orange as it dries.[6]On 20 March 1804, John Sibly, who was later named agent to the Osage Indians, wrote to Thomas Jefferson from Natchitoches on the Red River in Louisiana. Sibley had found in that vicinity “in … Continue reading The far-reaching roots are sheathed in a dark orange bark. In autumn the shiny green leaves turn to a glistening golden-yellow.

Osage Orange Flowers

© 2002 Steve Baskauf. From the Bio Images web site of Vanderbilt University, at http://bioimages.vanderbilt.edu

Macula pomifera is a diúcious species: Male (stamenifrous) flowers grow on male Osage orange trees; female inflorescences bear the (inedible) fruit of female (pistilliferous) flowers on female trees.

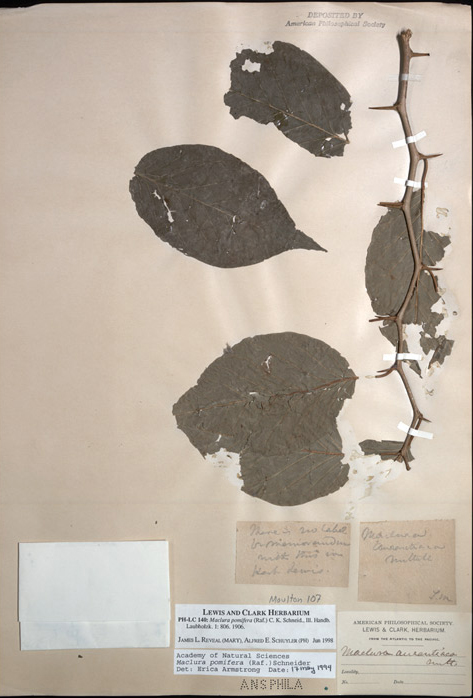

Lewis’s Specimen

This is one of the more problematic of the 133 or 134 known botanical specimens collected by Lewis and Clark.[7]Many of those species are represented by more than a single herbarium sheet. Of that number, 179 specimens are on permanent loan to the Academy of Natural Sciences by the American Philosophical … Continue reading Most of the sheets in the collection have annotations or labels that give some indication of when and where the specimens were collected. A few of the labels (on thick bluish or reddish paper) are in Lewis’s hand, but most of his original remarks were copied by Frederick Pursh onto small pieces of white paper, which contain the earliest information available today. This is one of only three for which neither places nor dates are known, which accounts for Thomas Meehan’s memo that there was no label or memorandum with it when he got it from the American Philosophical Society. The folded piece of white paper at lower left is a small envelope or “packet” to hold pieces of the specimen that might have been loose when it was first mounted, or might have fallen off afterwards.

Lewis’s letter to Jefferson containing his 500-word description of the tree was dated 26 March 1804. Only twice was the “Osage Apple” mentioned in the journals, both at Camp Dubois before the expedition officially began. Clark wrote in his Remarks for 7 April 1804: “the leaves of Some of the Apple trees have burst their coverts and put fo[r]th.” Three days later, with daily temperatures at sunrise still well below freezing, he observed: “no appearance of the buds of the Osage Apple,” whereas the plum trees had already “put forth their leaves and flower buds.” Pierre Chouteau, a prominent St. Louis businessman and Indian agent to the Osages, told Lewis he had introduced the tree to the vicinity of the town in the late 1790s. Chouteau’s own saplings had as yet produced neither flowers nor fruit, which suggests that the specimens Clark saw were about the same age.

The dates of Lewis’s and Clark’s references to the “Osage apple” notwithstanding, it is doubtful that either of them collected this thorn-studded branch and those few leaves in the spring of 1804. The tree is deciduous, that is, leaves fall from it in the late fall or early winter, and are replaced late in the following spring. This specimen has fully mature leaves that would normally not be seen until late spring or early summer. In fact, the plant flowers in the spring, and it is surprising that no flowers or even buds are present. Again, this suggests the specimen was made in mid to late summer. As noted above, Clark comments that when he observed the tree, buds were not yet present. Lewis specifically mentioned in his letter to Jefferson that he was sending young cuttings (“slips”), which could have been easily harvested in April since the Osage orange sends up shoots from its far-reaching roots. He said nothing about a pressed specimen. Therefore, inasmuch as this specimen has traditionally been regarded as a Lewis and Clark collection, and despite the absence of a label in either explorer’s hand, it must continue to be considered as having been collected by one of them, and that could only have been done after the expedition returned to St. Louis in September 1806.

Scientific Nomenclature

William Maclure (1763-1830)

Portrait by Charles Willson Peale, ca. 1800

Ewell Sales Steward Library. The Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia

Maclure was president of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia (1817-39), a member of the American Philosophical Society, a social activist and the “father of American geology.” In 1826, he boarded the keelboat Philan-thropist–the “Boatload of Knowledge”–along with a dozen other writers, educators, scientists and artists, including Robert Owen (1801-1877), Charles-Alexandre Lesueur (1778-1846), and Thomas Say (1787-1834). The party cruised down the Ohio to settle at the utopian village of New Harmony, Indiana. Maclure’s principal achievement there was his founding of the Working-men’s Institute, which included the first library in Indiana. An Osage orange tree, possibly planted by Maclure, still grows in front of the house he occupied at New Harmony.

As cryptic as it may appear, any professional botanist can read the entire chronological history and justification of a plant’s classification, or taxonomy, in an abbreviated tracing such as the one that follows the heading on the Lewis and Clark Herbarium label at lower center of the specimen sheet shown here. The currently accepted Latin binomial consists of the name of the genus, Maclura, and the species denominator, or “specific epithet,” pomifera. The abbreviation “Raf.” in parentheses signifies that the first botanist to identify this specimen was Constantine Rafinesque (1783-1840). However, “C. K. Schneid., Ill. Handb. Laubholzk. 1:806” relates that Camillo Karl Schneider (1876-1951), a German botanist, garden architect, horticultural journalist, and author of several books on trees, proposed the botanical name by which the Osage orange tree is known today. He published it in his Illustriertes Handbuch der Laubholzkunde, a monumental illustrated manual on woody cultivated plants, which appeared in twelve parts arranged in two volumes between 1904 and 1912. The name Maclura pomifera was entered on page 806 of the first volume, which was published in 1906.

Soon after the expedition’s end, Rafinesque saw saplings growing from slips in Bernard McMahon’s garden in Philadelphia—which was part of St. Peter’s Churchyard—and may have heard details about the fruit from Lewis in person, or from someone to whom Jefferson had conveyed the substance of Lewis’s letter. In any case, in December 1817 he designated it Ioxylon pomiferum (“poison apple”), basing his description on garden plants growing in Philadelphia.[8]When Rafinesque died in 1840, his herbarium was obtained by Elias Durand, who was then at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. Unfortunately, Durand kept only a few of Rafinesque’s … Continue reading The following year, Thomas Nuttall (1786-1859) described the species without acknowledging Rafinesque’s earlier name (about which Nuttall may not even have known). He proposed Maclura in honor of his friend, geologist William Maclure. Nuttall’s specific epithet was aurantiaca, meaning “orange-colored.” In 1906, the German dendrologist Camillo Karl Schneider (1876-1951), aware of Rafinesque’s name, ioxylon, proposed Maclura pomifera, purposely pairing Nuttall’s generic designation with Rafinesque’s specific epithet as required by the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature. The pomifera remains the only species in this monospecific genus.

Hardwood and Hedgerows

Osage orange is a very hard, heavy wood. Cottonwood and ponderosa pine, from which the Corps carved its dugout canoes, weigh 24 and 30 pounds per cubic foot, respectively; Osage orange weighs 48.22 pounds per cubic foot. It will hold a screw firmly if the hole is piloted first, but an attempt to drive a nail into this wood will test the temper of the nail and the temper of the nailer. Partly because of its density, it is one of the most durable woods in North America. When hedge-apples gave way to maintenance-free barbed wire fences in the 1870s and 80s the tough tree’s rot-proof and mostly insect-proof stems made fence posts that could outlast the wire. Osage orange stems even served briefly as railroad ties, although to a limited extent, owing to the difficulty of finding enough long and suitably straight logs, not to mention the herculean effort it took to drive spikes into it. Today it is apparent that Osage orange will even tolerate road-salt and urban air pollution.

Farmers on the Great Plains in the 1850s called them “hedge-apples.” When planted, nursed, and pruned to keep them in line, Osage oranges produce a thorny, tangled thicket of tough and durable little trees that made a windbreak and hedgerow up to 20 feet high that was impenetrable by man and beast alike. It was cultivated so widely throughout the country during the 19th century that it is now found in all but ten of the lower 48 states. Botanists today can only spec-ulate that its original habitat was limited to southwest Arkansas, southeast Oklahoma, and north Texas.

The proper noun is said to be a phonetic transliteration of the tribe’s Indian name, Wazhazhe,[9]Clark thought their own name for themselves sounded more like Bar-har-cha. “List,” in Moulton, Journals, 3:390. via Canadian French traders into “Osage,” from the Indian tribe of the same name.[10]Eagle/Walking Turtle, Indian America: A Traveler’s Companion, 4th edition (Santa Fe, New Mexico: John Muir Publication, 1995), 79. According to tribal legend, the origin of the tribe in the lowest of the four upper regions of the underworld resulted from the combination of two clans, the Tsishu, or peace people who lived on roots, and the Wazhazhe, or war people who lived on animals, which they killed with arrows shot from bows made of the strong, flexible wood of this tree.

Patrick Henry’s Red Hill Tree

Another Osage orange tree on the East Coast has borrowed a comparable measure of fame from another great American. It stands some miles southeast of Monticello in the front yard of Red Hill, where Patrick Henry spent the last five years of his life, 1794-99.[11]“Red Hill: Patrick Henry National Memorial,” http://www.redhill.org/tree.htm. Accessed 12 November 2005. It is an awesome physical specimen, rising sixty feet in height and spreading an 85-foot canopy on a compound trunk consisting of five conjoined stems totalling almost 27 feet in circumference. Its age has recently been estimated, conservatively, at 300 years.

If that figure is correct, how did the tree get to the Piedmont of Virginia, a thousand miles east of its native habitat, nearly forty years before the first English settlers arrived? The most plausible explanation rests on archaeological evidence that Indians were living on the banks of the Staunton River in the vicinity of Red Hill by at least 1670. Perhaps, as the most important materiel in Nature’s high-tech arsenal, the cutting from which this tree grew was passed along the North American Indian trade network, or maybe even brought back from the Red River Valley as a trophy or a souvenir by some prehistoric Native American hunter or tourist.[12]Nancy Ross Hugo, “The Mystery of Patrick Henry’s Osage-Orange,” American Forests (Summer 2003), 32-35. The bow and arrow began to supplant the atlatl in North America about 1,600 … Continue reading

Notes

| ↑1 | Donald Jackson, Thomas Jefferson & the Stony Mountains: Exploring the West from Monticello, Reprint, with a foreword by James P. Ronda (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1993), 161 n.52. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The design that Bradbury described resembled the “war hatchet” Clark sketched in his journal on 28 January 1804. |

| ↑3 | Maximilian Prince of Wied’s Travels in the Interior of North America, during the years 1832–1834. In: Reuben Gold Thwaites, ed., Early Western Travels, 1748-1848, 1906, (vol. 22-25), 189. |

| ↑4 | Pierre Chouteau (1758-1849) and his older brother Auguste (1749-1829) were the leading entrepreneurs in St. Louis and Upper Louisiana at the turn of the 19th century. They were especially influential in maintaining good relations between the U.S. government and the Osage Indians, the tribe Jefferson maintained was “the great nation South of the Missouri, . . . as the Sioux are great North of that river.” Secretary of War Henry Dearborn appointed Pierre Chouteau as agent to all Indian tribes in Upper Louisiana. Pierre’s home in St. Louis was the unofficial headquarters for Lewis and Clark during the winter of 1803-04. Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, with Related Documents, 1783-1854, 2d ed., 2 vols. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:199-200. William E. Foley and C. David Rice, The First Chouteaus: River Barons of Early St. Louis (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1983), 105-118. |

| ↑5 | Jackson, Letters, 1:170-71. Clark’s description of the “great Osage vilage,” situated on the upper Osage River and the Arkansas River, is the first item in his “List of the Names of the different Nations & Tribes of Indians Inhabiting the Countrey on the Missourie and its Waters,” which he assembled during the winter at Fort Mandan. Moulton, Journals, 3:390-91. The village was situated at the main forks of the Osage River in west-central Missouri near the Oklahoma-Missouri border. The principal habitat of the tree was along the Red River of the South where it crosses the Texas panhandle. |

| ↑6 | On 20 March 1804, John Sibly, who was later named agent to the Osage Indians, wrote to Thomas Jefferson from Natchitoches on the Red River in Louisiana. Sibley had found in that vicinity “in almost exhaustless quantities a yellow wood the French call it Bois d’arc, or Bow wood, . . . it has a beautiful fine grain, takes a polish like a Varnish when it is Nearly the Patent yellow Colour it is more elastic than any other wood; the Indians use it for Bows, and the Inhabitants sometimes for Ax helves and handles for other Tools, I think it would be highly esteem’d by Cabinet makers for Inlaying & Fineering, and by Turners. But probably would be more Valuable as a dye wood; a few days ago I had some experiments made in colouring with it and have taken the Liberty of Inclosing to you some samples of colours it produs’d. . . . I have no doubt by a person skill’d in dying a very numerous Variety of Colours might be produc’d from this wood as the Basis; from an experiment I believe the Colours will Neither wash out; nor fade by washing.” Doug Erickson, Jeremy Skinner, and Paul Merchant, eds., Jefferson’s Western Explorations (Spokane, Washington: Arthur H. Clark, 2004), 309. Sibley was correct on all counts. It was used to make khaki dye during World War I, and is still widely used as a yellow dye by artists and craftspersons. |

| ↑7 | Many of those species are represented by more than a single herbarium sheet. Of that number, 179 specimens are on permanent loan to the Academy of Natural Sciences by the American Philosophical Society. Nine or perhaps ten more are to be found at the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, England. A previously unknown Lewis specimen of a grass gathered in North Dakota in 1806 was discovered at Kew in 2005. |

| ↑8 | When Rafinesque died in 1840, his herbarium was obtained by Elias Durand, who was then at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. Unfortunately, Durand kept only a few of Rafinesque’s plant specimens, discarding thousands of them, including many that Rafinesque had used to characterize new species as well as types. In the case of this species, it is not known if Rafinesque actually had a specimen in his herbarium, but it is likely he did. |

| ↑9 | Clark thought their own name for themselves sounded more like Bar-har-cha. “List,” in Moulton, Journals, 3:390. |

| ↑10 | Eagle/Walking Turtle, Indian America: A Traveler’s Companion, 4th edition (Santa Fe, New Mexico: John Muir Publication, 1995), 79. |

| ↑11 | “Red Hill: Patrick Henry National Memorial,” http://www.redhill.org/tree.htm. Accessed 12 November 2005. |

| ↑12 | Nancy Ross Hugo, “The Mystery of Patrick Henry’s Osage-Orange,” American Forests (Summer 2003), 32-35. The bow and arrow began to supplant the atlatl in North America about 1,600 years ago, itself to be superseded upon the arrival of gun-totin’ Europeans. |