The Tillamooks, cordial hosts and friends to the visiting Americans in 1806, may have numbered about 2,200 persons at that time. By 1841 sexually transmitted diseases, smallpox, measles, and influenza epidemics contracted from white traders reduced them to about 400 souls. As immigrant settlement increased, the Indians were even attacked by self-styled white “exterminators.”

Welcoming Pole at NeCus’ Park

by Guy Capoeman

Courtesy National Park Service, Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.

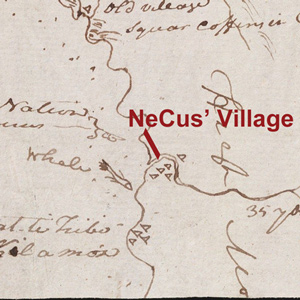

NeCus’ Village was a thriving village at Ecola Creek, and the Lewis and Clark Expedition journals provide the first written account of this community. It is here that Clark and his party saw the whale and Hugh Hall‘s life was saved by the efforts of a Tillamook woman. The 10-foot cedar “welcoming pole” shown above is of a Clatsop man, and the park was developed in cooperation with the Clatsop-Nehalem Confederated Tribes.[1]“NeCus’ Park,” National Park Service, Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail, www.nps.gov/places/necus-park.htm accessed 4 January 2023; “A Village on the Ecola Shore: … Continue reading

Early in the 1850s most of the survivors, along with the remnants of about 15 other Indian nations in northwestern Oregon, were marched from their homes to a 69,000-acre Coastal Reservation on Oregon’s Salmon River, 60 miles south of the Columbia and 20 miles inland.

The General Allotment (Dawes) Act of 1887, which gave 160 acres of land to the head of each Indian household, was intended to ease the River Indians into the American mainstream as middle class farmers and, in the time-honored conservative catch-phrase, “get the government out of their lives.” However, it also required that “surplus” reservation land be surrendered to the U.S. Government. By the early 1950s there were only 597 acres left in their reservation and so, in the spirit of economy, a government-appointed trustee was directed to dispose of them. That he did—to private interests, for $1.10 per acre; the income was distributed to tribal members at $35 per person. In 1970, tribal property consisted of 2.5 acres and a tool shed next to the tribal cemetery.

In a gesture of reconciliation, the Restoration Act of 1983 restored recognition to the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde. In 1988 the Grand Ronde Reservation Act gave back to the tribe 9,811 acres of public timberland, on three conditions: First, that the tribes refrain from competing with the local timber market for 20 years; second, that 30 percent of any income from the timber be used for tribal economic development; and third, that the tribe pay 20 years’ worth of back taxes to the two counties in which the timberland lay.

For Further Reading:

Jan Halliday & Gail Chehak, Native Peoples of the Northwest (Seattle: Sasquatch Books, 1986), pp. 140-42.

William Canby, Jr., American Indian Law (2nd ed., St. Paul: West Publishing Company, 1991).

Sharon Malinowski, et al., eds., The Gale Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes (4 vols., Detroit: Gale Research, 1998).

Selected Encounters

January 3, 1806

An agreeable food

Clatsop villagers come to Fort Clatsop to sell whale blubber and dogs. Lewis finds the latter “an agreeable food”. Two men are sent to fetch long-overdue Pvts. Willard and Weiser from the salt works.

January 6, 1806

Sacagawea's plea

At Fort Clatsop, Sacagawea pleads to be permitted to see a beached whale, and her wish is “indulged”. Half-way to the salt works, Clark’s group—including Sacagawea—have a clear night with a “Shiney” moon.

January 7, 1806

Climbing Clark's Mountain

Clark’s small group walks several miles along the beach to reach the Salt Works at present Seaside, Oregon. From there, they climb up and over the very “Pe Shack” (bad) Tillamook Head—Clark’s Mountain.

Over Tillamook Head

Clark's point of view

by Joseph A. Mussulman

After passing the salt works and continuing along the “round Slippery Stones under a high hill,” Clark related, “my guide made a Sudin halt, pointed to the top of the mountain and uttered the word Pe Shack which means bad, and made Signs that we . . . must pass over that mountain.

January 8, 1806

A night at Ecola

From Clark’s Point of View above Ecola, Clark’s group enjoys the “grandest and most pleasing prospects”. At Ecola, Tillamook Indians trade a little whale blubber, and Pvt. McNeal’s life is threatened.

Ecola

Whale tale

by Joseph A. Mussulman

By the time Clark and his party got to present-day Cannon Beach, Oregon, on 8 January 1806, the locals had picked the dead whale’s 105-foot-long carcass clean.

NeCus’ Village

by Douglas Deur, Tricia Gates Brown

Before the resort town of Cannon Beach, Oregon, a Tillamook tribal village—NeCus’—sat along the tiny brackish bay where Ecola Creek crosses the sandy beach. The Lewis and Clark Expedition journals provide a tantalizing but fragmentary glimpse of this community.

January 11, 1806

Lost canoe

At Fort Clatsop, careless paddlers fail to secure the Chinookan canoe, and it floats away. After visiting Kathlamets leave to barter with the Clatsops, Lewis describes the Columbia River trade network.

January 13, 1806

Out of candles

At Fort Clatsop near present Astoria, Oregon, elk tallow is rendered to make new candles, and Lewis finds that elk do not have enough fat. He also describes the ship trade among the area’s Nations.

January 23, 1806

A lack of brains

At Fort Clatsop, Lewis laments a “want of [animal] branes” and lye soap with which to make leather. He sends Pvts. Werner and Howard to fetch some salt from the Salt Makers’ Camp at present Seaside, Oregon.

January 25, 1806

Critical updates

At Fort Clatsop near the Pacific Ocean, the captains receive several updates: a report from the salt makers, the location of two previously missing hunters, and new information about the Tillamooks.

March 18, 1806

Stealing a canoe

Near the Pacific Ocean, four men steal and hide a Clatsop canoe. The captains write a short description of the expedition which they distribute among the local residents.

March 21, 1806

Weather delay

At Fort Clatsop near the Pacific Ocean, bad weather prevents the expedition from leaving for home. Provisions are low, so hunters are dispatched and eulachon purchased from some visiting Clatsops.

March 22, 1806

Giving away the fort

In anticipation of leaving for home tomorrow, Fort Clatsop is given to Coboway, and hunters are sent up the Columbia. Dried eulachon and a dog are purchased, and the canoes are plugged with mud.

Notes

| ↑1 | “NeCus’ Park,” National Park Service, Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail, www.nps.gov/places/necus-park.htm accessed 4 January 2023; “A Village on the Ecola Shore: Revisiting the Lives and Landscapes of the “No-Cost Tribe of the Kil a mox Nation,” We Proceeded On 48, no. 1 (February 2022): 20–29. |

|---|

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.