Linguistically, the Kathlamets spoke their own Chinookan dialect. Culturally, they were part of the Lower Chinook residing primarily on the south shores of the Columbia River between Tongue Point and the Kalama River. Their name is derived from galámat, a village at Aldrich Point—previously named Cathlamet Point.[1]Michael Silverstein, Handbook of North American Indians: Northwest Coast Vol. 7, ed. Wayne Suttles (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1990), 534, 544.

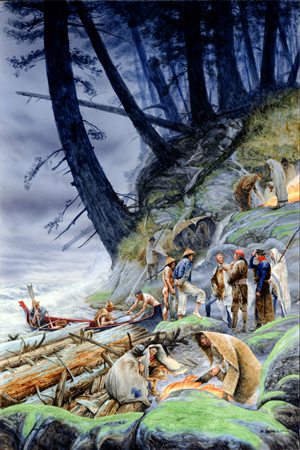

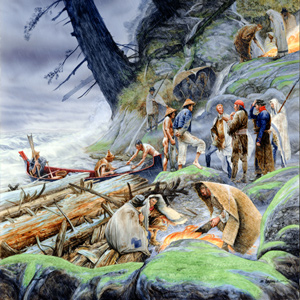

The expedition journalists recorded several encounters with the Kathlamets, or Cathlamets, during their stay at the Pacific coast during the 1805–06 winter. On 11 November 1805, while hunkered down in a “dismal nitch” on the north side of the Columbia, a Kathlamet canoe “loaded with fish of Salmon Spes. Called Red Charr” pulled to shore. After buying 13 sockeye, Clark marveled:

those people left us and Crossed the river (which is about 5 miles wide at this place) through the highest waves I ever Saw a Small vestles ride. Those Indians are Certainly the best Canoe navigaters I ever Saw.

The captains also noticed a Kathlamet man decked out in sailor’s clothes. Speaking in Plains Sign Language the captains mistakenly heard that they got those clothes from white people living further down the river. However, the expedition’s hopes of finding a post or trading ship were never fulfilled (see The Empty Anchorage). Throughout the winter, trade with the Kathlamets brought salmon, sturgeon, eulachon, and wapato bulbs, a much–needed variety in the expedition’s bland diet of elk meat.

Shortly after the expedition, many Kathlamets moved to the north side of the river joining with similar–speaking The Wahkiakums. In an 1851 treaty, the Kathlamets ceded lands to the United States where John Jacob Astor’s Fort Astoria and the British Fort George had been located and the city of Astoria is presently. Populations dwindled due to dispersal and disease, and today, there are no speakers of the Cathlamet dialect[2]Robert H. Ruby, John A. Brown, and Cary C. Collins, A Guide to the Indian Tribes of the Pacific Northwest (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010), 15–16. Descendants have joined with Chinook Indian Tribe/Chinook Nation, and Chinuk Wawa, a pidgin hybrid language used during the European trade era, is preserved and taught.[3]Tony A. Johnson, Chinookan Peoples of the Lower Columbia, ed. Robert T. Boyd, et al. (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2013), 5, 273.

Selected Pages and Encounters

November 11, 1805

Kathlamet visitors

The expedition makes the best of their poor location in a small niche exposed to high waves and driving rain. Five Kathlamet visitors skillfully cross the Columbia in a canoe loaded with fish.

November 26, 1805

Crossing the Columbia

Several miles above the mouth of the Columbia, they safely cross the river and continue west along the southern shore. At a Kathlamet village, the villagers want blue beads and blue, red, or brown blankets.

December 3, 1805

Food for the sick

At their Tongue Point bivouac, spirits lift when the morning proves fair and fresh elk meat arrives. Clark and several enlisted men find healing in the wapato and marrow.

January 10, 1806

Šax̣awaq̀ap visits

After an early start at the salt makers’ camp, Clark hikes and canoes well into the dark to return to Fort Clatsop. During the day, a dozen Kathlamets visit Lewis and elk become scarce.

January 11, 1806

Lost canoe

At Fort Clatsop, careless paddlers fail to secure the Chinookan canoe, and it floats away. After visiting Kathlamets leave to barter with the Clatsops, Lewis describes the Columbia River trade network.

January 13, 1806

Out of candles

At Fort Clatsop near present Astoria, Oregon, elk tallow is rendered to make new candles, and Lewis finds that elk do not have enough fat. He also describes the ship trade among the area’s Nations.

January 15, 1806

Lewis's new fur coat

Lewis’s new fur coat—made by local Indians from bobcat and perhaps mountain beaver robes—is brought to Fort Clatsop. The captain also describes Chinookan hunting methods and weaponry.

January 20, 1806

Five plant specimens

At Fort Clatsop, Lewis prepares five new plant specimens and describes roots eaten by local Chinookan Peoples. The captains worry about the rate at which they are going through their supply of elk.

March 11, 1806

Living "in clover"

Sgt. Pryor returns to Fort Clatsop in a borrowed canoe full of fish and wapato, and Lewis says they are living in clover. Lewis describes the western fence lizard and rough-skinned newt.

March 17, 1806

A new canoe

Drouillard returns to Fort Clatsop with a canoe purchased with Lewis’s uniform coat and suggests they take another in lieu of the six ‘stolen elk ‘. Lewis describes seaweed and lists ship captain names.

March 21, 1806

Weather delay

At Fort Clatsop near the Pacific Ocean, bad weather prevents the expedition from leaving for home. Provisions are low, so hunters are dispatched and eulachon purchased from some visiting Clatsops.

Up the Columbia

Heading home

by Barbara Fifer, Joseph A. Mussulman

Homeward bound in April 1806, the Lewis and Clark Expedition traveled through the Columbia Gorge and pitched camps on its north side. Their passage was tense and unpleasant, with Indians taking small goods regularly.

March 24, 1806

Stolen canoe claimed

On their way to present Aldrich Point, they cross shallow waters crowded with islands, and a Kathlamet man guides them to the correct channel. The guide claims he is the owner of one of their canoes.

March 25, 1806

Downstreamer Chinooks

As they paddle along the south shore of the Columbia, the expedition sees Downstreamer Chinooks trolling for sturgeon. After fifteen miles, they find a popular camping spot at the present Clatskanie River.

March 26, 1806

At Fanny's Bottom

After a wet night, they paddle approximately 18 miles up the Columbia River and camp on an island near an area they call “fannys bottom”. Lewis describes eagles and substitutes for tobacco.

March 27, 1806

Generous Skilloots

Near present Deer Island, Oregon, some generous Skilloots give away food with hopes that the expedition hunters will hunt with them. Lewis describes the area’s trees and prepares a salmonberry specimen.

Notes

| ↑1 | Michael Silverstein, Handbook of North American Indians: Northwest Coast Vol. 7, ed. Wayne Suttles (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1990), 534, 544. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Robert H. Ruby, John A. Brown, and Cary C. Collins, A Guide to the Indian Tribes of the Pacific Northwest (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010), 15–16. |

| ↑3 | Tony A. Johnson, Chinookan Peoples of the Lower Columbia, ed. Robert T. Boyd, et al. (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2013), 5, 273. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.