In five battered dugout canoes, the expedition paddles down the Columbia River—a river that they know will take them to the Pacific Ocean.

They safely pass a series of rapids and falls between Celilo Falls and the Cascades of the Columbia. In the Columbia River Gorge, they see stunning geologic features.

The river calms, now affected by tides, and they enter one of the most populated areas of their entire journey with numerous villages of Upper and Lower Chinook.

They find the Columbia River Estuary is miles long and miles wide. Everyone must hunker down in small niches several days before they can reach the end of their water journey at Baker Bay.

At Station Camp, the captains survey the party as to where they would like to spend the winter. Everyone’s opinion—including York and Sacagawea—are written down. They decide to cross the river where according to the Clatsops, there are many elk.

They set up a camp on a narrow spit of land on the opposite side—present Tongue Point at Astoria, Oregon. Lewis takes a small party to find a suitable location to build a fort, but when he fails to return after five days, Clark begins to worry.

The Wahkiakums

by Kristopher K. Townsend

The Wahkiakums exemplify the complexities encountered when trying to classify Chinookan peoples. Linguistically, they spoke the Upper Chinookan Clackamas dialect. Culturally, they were related to the Lower Chinookan Clatsops and Chinooks proper. They resided primarily along the north side of the Columbia between Grays Bay and Cathlamet, Washington.

The Wascos and Wishrams

by Barbara Fifer

At The Dalles lived Upper Chinookan people, the Wishrams on the Columbia’s north (Washington) side—and their allies the Wascos on the south (Oregon) side—who were the main masters of the regional trading center. The Lewis and Clark Expedition encamped on the north side.

The Cowlitz

The Cowlitz proper were Southwestern Coast Salish peoples living mainly along the Cowlitz River. The people were blenders. Those living among the Chinookan Skilloots intermarried and may have been indistinguishable when the expedition passed the “Cow-e-lis’-kee” River.

The Multnomahs

by Kristopher K. Townsend

When interviewing William Clark and George Shannon to prepare his condensation of the expedition journals, Nicholas Biddle wrote in his notes that “The Multnomah nation is placed on the Wappatoe Island opposite the mouth of the Multh. river and the inlet which forms the island. . . . the neighbors speak of the Multnomah nations as great &c.”

The Yakamas

The Yakama’s first Euro-American contact was the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1805. The captains named the people Chim’-nah-pum’ which was the name of the village at the mouth of the Yakima River.

The Umatillas

After emerging from the Wallula Gap on 19 October 1805, Clark came across some Umatillas hiding in their lodges, and he committed a serious faux pas by entering without permission.

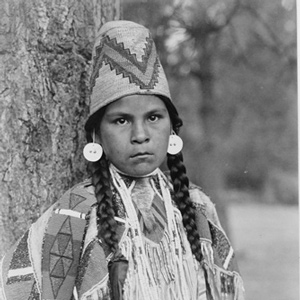

The Nez Perce

by Kristopher K. Townsend

First encountered September 1805 when John Colter met them on Lolo Creek near Travelers’ Rest, they would remain with the expedition in one way or another until 25 October 1805 saying their goodbyes at Rock Fort at The Dalles of the Columbia River. They were together again between 23 April 1806 and 4 July 1806, the expedition’s longest period of contact with any Native American Nation.

The Walla Wallas

Walla Wallas, sometimes Waluulapam and sometimes on this site as Walula, are a Sahaptin-speaking indigenous people that lived primarily along their namesake river. There has been disagreement among historians regarding the nation’s etymology.

The Watlalas

by Kristopher K. Townsend

Watlala was the name of a key Upper Chinookan village at the Cascades of the Columbia. The name has been extended by many to mean the tribe more often called the Cascades. The captains called them the Shahala, meaning ‘those upriver.’ The natural constriction of the river provided the people with a fishery and a good measure of control over those who traveled up and down the river. As a result, the Cascade Clahclellah village which the expedition visited on 31 October 1805 and 9 April 1806 was a major trade center before and during white contact.

The Clatsops

by Kristopher K. Townsend

The creek where Coyote built his legendary house—today’s Neacoxie Creek—flows north to south bisecting nearly the length of the Clatsop Plain. A village at the estuary created by the ocean, Neacoxie Creek and the larger Necanicum River is Ne-ah-coxie Village. Nearby were three other Clatsop villages, and for a short time, a salt works built by soldiers from the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

The Lower Chehalis

by Kristopher K. Townsend

The Lewis and Clark Expedition encountered the Lower Chehalis mainly during their stay at Station Camp on Baker Bay. In the journals, the people’s name is spelled Chieltz and Chiltch.

The Chinooks

by Kristopher K. Townsend

Today, Chinook often refers to the politically united Lower Chinook, Clatsops, Willapas, Wahkiakums, and Kathlamets. To Lewis and Clark, the Chinook were the people living on the north side of the Columbia River’s estuary. When Lewis and Clark met them, the people of Baker Bay had been trading with European ships for more than a decade.

The Kathlamets

by Kristopher K. Townsend

The expedition journalists recorded several encounters with the Kathlamets, or Cathlamets, during their stay at the Pacific coast during the 1805–06 winter. On 11 November 1805, while hunkered down in a “dismal nitch” on the north side of the Columbia, a canoe “loaded with fish of Salmon Spes. Called Red Charr” pulled to shore. After buying 13 sockeye, Clark marveled.

The Chilluckittequaws

White Salmon and Smock-shops

by Kristopher K. Townsend

Wind Mountain was at the western extent of a series of Upper Chinookan villages called by Lewis and Clark the “Chilluckkittequaw nation.” Apparently, when asked for a tribal name, the captains were given the word for ‘he pointed at me’. Chilluckittequaw was adopted as their name a century later by early ethnographer Frederick Hodge. Between Wind Mountain and Hood River, nine villages have been identified, some overlapping with Klickitats

The Skilloots

by Kristopher K. Townsend

The Skilloot were an Upper Chinookan group that spoke the Clackamas dialect of the Chinookan language. They were located on both sides of the Columbia River above and below the mouth of the Cowlitz. At first, the captains applied the name over a much wider area, perhaps misinterpreting a similar expression meaning ‘look at him!’. Cape Horn, a few miles east of Washougal, was named sqúlips, and could be the origin of the tribe’s name.

The Teninos

At the time of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, the Teninos lived on the north side of the Columbia River and controlled key fishing areas on the river’s south side. Tenino was a small village at Five Mile Rapids above The Dalles of the Columbia.

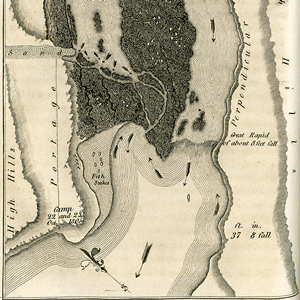

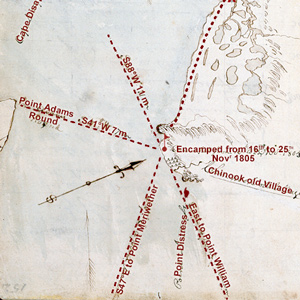

Clark’s Columbia River Maps

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Clark made a series of maps illustrating the Columbia River suitable for future navigators.

Synopsis Part 4

Lemhi Valley to Fort Clatsop

by Harry W. Fritz

After trading for horses with Sacagawea’s people, the expedition turned north and then west, on what would indisputably be the most exhausting and debilitating segment of the entire journey, the passage across the Bitterroot Mountains.

Columbia River Basalts

by John W. Jengo

The region of the lower Snake River and the Columbia River’s course through the Columbia Plateau and Gorge experienced volcanic activity starting some 55 million years ago, although the expedition would primarily encounter rock units of Miocene-age.

Meeting the Columbia

A welcoming fanfare

by Joseph A. Mussulman

In the afternoon of 16 October 1805, the expedition portaged around “the last bad rapid as the Indians Sign to us”–the last on the Snake River, that is–and soon arrived at the “Great River of the West,” the Columbia.

Through Wallula Gap

Yelleppit and Sacagawea help out

by Joseph A. Mussulman

They encountered several rapids that nineteenth of October, including “a verry bad one” about two miles long. Clark climbed a 200-foot “clift” from which he could see many miles across the high desert.

Hat Rock

The enlisted men must have recognized it at a glance, this pile of columnar basalt all together resembling a well-weathered gentleman’s hat with a work-worn brim. Two centuries later, it would be one of the few Lewis and Clark landmarks left above Columbia River.

Columbia River near Blalock

Greatest chief

by Joseph A. Mussulman

This scene’s most arresting feature is still the “high mountain of emence hight covered with Snow” on the photo’s horizon. Clark mistook it for Mount St. Helens. The Indians called the mountain Pahtoe. Since 1838 it has been known as Mount Adams.

The Deschutes River

by Barbara Fifer

The fall salmon run was ending when the Corps arrived at the Great Falls of the Columbia, several miles below the mouth of Towarnehiooks, with some native people still at the river, fishing with gigs and nets and processing their salmon harvest.

The Cliffs at John Day

Columbia River rock falls

by John W. Jengo

The 21 October 1805 rock fall geologic notation is likely referring to mass-wasting features along a fourteen-mile long stretch of dramatically steep slopes visible today between Blalock Canyon and the John Day River.

Miller Island

River of the falls

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Near the west end of the island, they passed a sizeable tributary local Indians called To war ne hi ooks. The journalists left us no hint that the word they heard as Towarnehiooks was a Chinookan expression meaning “enemies.”

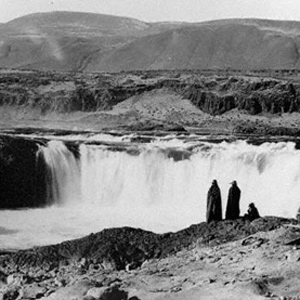

Celilo Falls

Great mart of the west

by Barbara Fifer

The Corps of Discovery reached a many-faceted barrier, Celilo Falls, which required a portage. The falls proved to be the beginning of fifty-some river miles that also held The Short and Long Narrows (jointly called The Dalles), and ended with the lengthy Cascades of the Columbia.

Geology of The Dalles

by John W. Jengo

Over four days (22-25 October 1805) the expedition would be navigating through one of the most exciting and difficult stretches of the entire water route to the Pacific. Several outstanding geological features were noted.

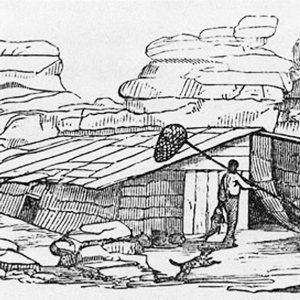

Flea Country

A multitude of fleas

by Joseph A. Mussulman

During the portage around the Falls of the Columbia River, as Biddle paraphrased it, “we found that the Indians had camped there not long since, and had left behind them multitudes of fleas.”

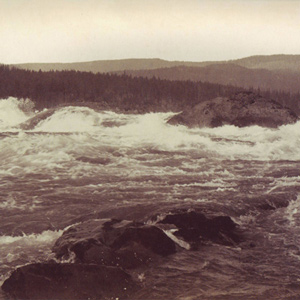

The Short and Long Narrows

A bad whorl and suck

by Barbara Fifer

Here the Columbia was “an agitated gut Swelling, boiling & whirling in every direction.” Even so, Cruzatte and Clark agreed that they could run the canoes through.

Fort Rock

Refuge at The Dalles

by Joseph A. Mussulman

The party “Came too, under a high point of rocks on the Lard. Side below a creek”—Quenett (“salmon”), now Mill Creek—a “Situation well Calculated to defend our Selves,” and duly named their bivouac “Fort Rock Camp.”

The Dalles

Through the Narrows

by Joseph A. Mussulman

There really was no need for him to have been on the defensive. Pierre Cruzatte cast a spell over the assembled Indians with his fiddle, which was much more effective than any pompous diplomatic talk.

The Columbia River Gorge

Its geologic origin

by John W. Jengo

The consolidated rocks that compose the Gorge were formed by a complex interplay of Columbia River Basalt Group flood basalt deposition and basin subsidence, along with contemporaneous folding and faulting—not the Glacial Lake Missoula floods.

Columbia Gorge Waterfalls

by John W. Jengo

William Clark: “Saw 4 Cascades caused by Small Streams falling from the mountains on the Lard. Side.”

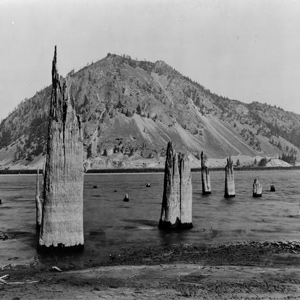

A Submerged Forest

by John W. Jengo

On 30 October 1805, Clark documented the presence of a submerged forest, which along with the burning bluffs of northeastern Nebraska, the “Burnt Hills” of North Dakota, and White Cliffs of the Missouri in central Montana, remain one of the expedition’s most famous geological observations.

Beacon Rock

A remarkable, high and detached rock

by Joseph A. Mussulman![]()

“a remarkable high detached rock Stands in a bottom on the Stard [starboard, the navigator’s right] Side & about 800 feet high and 400 paces around”

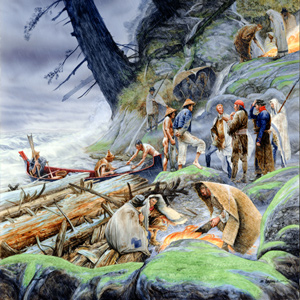

Cascades of the Columbia

The "Great Shute"

by Barbara Fifer

Clark described the Cascades as having a “Great Shute” where the Columbia dropped about twenty feet over both large and small rocks, “water passing with great velocity forming & boiling in a most horriable manner.”

Bonneville Dam

Through the Narrows

by Joseph A. Mussulman

The Bonneville Dam, completed in 1938, raised the level of this part of the Columbia seventy-two feet and permanently obliterated the place Lewis and Clark called the “Great Shute.”

Columbia River Dams

The rough places plain

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Bonneville Dam, was the first dam to be built on the Columbia River. The slackwater pool it impounds, called Lake Bonneville, eliminated the Cascades as a barrier to commercial shipping, and provided a deep, navigable channel for barges and tugs.

Rooster Rock at Crown Point

by John W. Jengo

The promontory of Crown Point comes to mind when Clark mentions in his notebook journal that the expedition camped “under a high projecting rock.”

Phoca (Seal) Rock

by John W. Jengo

The mid-river island identified as “Phoca” and “Seal rock” on one of William Clark’s route maps is a compact landslide block that detached from the Cape Horn headland.

The Sandy River

The "quicksand river"

by John W. Jengo

The expedition traveled out from under an ancient river channel frozen in time to a river discharging huge volumes of sediment in real time, the “quicksand river,” now known as the Sandy River.

Ridgefield National Wildlife Refuge

Horrid noise

by Joseph A. Mussulman

On the night of 4 November 1805 the expedition camped near a pond now called Post Office Lake. The next morning a weary, groggy Clark complained that he “could not Sleep for the noise” made by the numerous waterfowl.

Cascade Mountains at Dawn

by Joseph A. Mussulman

In 1838, a patriotic citizen started a campaign to change the Cascade Mountains into the “Presidential Range.” This was to include renaming Mount Hood after John Adams.

The Columbia River Estuary

"Great joy"

by Joseph A. Mussulman

When the sky cleared briefly at about noon on 7 November 1805, a rising cheer may have startled the myriad waterfowl in the area, for Clark wrote, “we are in view of the opening of the Ocian, which Creates great joy.”

Ocean in View?

Premature elation

by Joseph A. Mussulman

They fancied they could already see and hear the Pacific Ocean, although it was still more than 20 miles away, well beyond their horizon. Clark’s famous exclamation was another instance of the captains’ habit of reacting prematurely.

Grays Bay

Shallow bay

by Joseph A. Mussulman

On the morning of 8 November 1805, the Corps’ flotilla entered a “nitch” they called Shallow Bay and paused for their midday meal near the remains of an Indian village with “great numbers of flees which [we] treated with the greatest caution and distance.”

Point Ellice

"blustering point"

by Joseph A. Mussulman

It was “the most disagreeable time I have experienced,” Clark grumbled on 15 November 1805. “Confined on a tempiest Coast wet, where I can neither get out to hunt, return to a better Situation, or proceed on”

Station Camp

"the extent of our journey"

by Joseph A. Mussulman

“…this I could plainly See would be the extent of our journey by water, as the waves were too high at any Stage for our Canoes to proceed any further down ….”

The Station Camp Observations

16–24 November 1805

by Robert N. Bergantino

The morning of 16 November 1805 dawned “Clear and butifull.” At noon Clark took advantage of the conditions and made an observation of the sun’s altitude for latitude. He used the sextant and artificial horizon.

Cape Disappointment

"This Emence Ocian"

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Private Whitehouse thought his captains had named Cape Disappointment “on account of not finding Vessells there,” but it had received the name years earlier.

Arrival at the Pacific

Exploring Long Beach

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Clark was pleased that his men appeared “much Satisfied with their trip beholding with estonishment the high waves dashing against the rocks & this emence ocean.”

Bivouac at Tongue Point

A long and wet encampment

by Joseph A. Mussulman

As the Corps rounded Tongue Point the wind rose hard from the west, and heavy seas with torrential rain forced them back to the east shore of the narrow isthmus, where they huddled for ten miserable days.

Wheeler on the Columbia

Fish wheels and canneries

by Barbara Fifer, Joseph A. Mussulman

At The Dalles in 1902, a hospitable local citizen helped Wheeler make his way to the brink of the long narrow channel and chasm through which Lewis and Clark took their canoes, where he “overlooked the swirling waters as they boiled and raged.”

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.