“Of all the terrains the Lewis and Clark expedition traversed between 1803 and 1806, the route down the Snake and Columbia Rivers, amongst dark menacing rocks and through ferocious whitewater rapids, was perhaps the most thrilling, dramatic, and geologically fascinating. What Sergeant Patrick Gass observed to be “so much uniformity in the appearance of the country,” belied an exceptionally active and relatively recent geologic history.”

Related Pages

From the moment they dipped their paddles into the Snake River, the Lewis and Clark expedition would not only be following the path of multiple flood basalt flows, but also the route of the colossal Lake Missoula floods that so markedly scoured the basaltic landscape.

The 21 October 1805 rock fall geologic notation is likely referring to mass-wasting features along a fourteen-mile long stretch of dramatically steep slopes visible today between Blalock Canyon and the John Day River.

![]()

“a remarkable high detached rock Stands in a bottom on the Stard [starboard, the navigator’s right] Side & about 800 feet high and 400 paces around”

The consolidated rocks that compose the Gorge were formed by a complex interplay of Columbia River Basalt Group flood basalt deposition and basin subsidence, along with contemporaneous folding and faulting—not the Glacial Lake Missoula floods.

Hat Rock

The enlisted men must have recognized it at a glance, this pile of columnar basalt all together resembling a well-weathered gentleman’s hat with a work-worn brim. Two centuries later, it would be one of the few Lewis and Clark landmarks left above Columbia River.

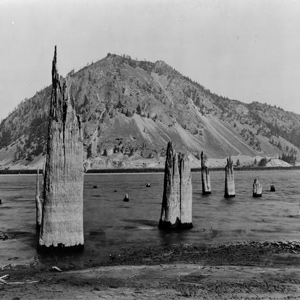

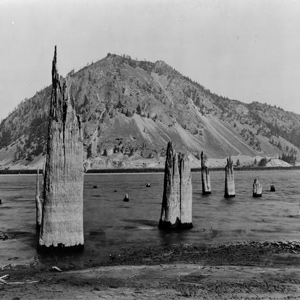

A Submerged Forest

by John W. Jengo

On 30 October 1805, Clark documented the presence of a submerged forest, which along with the burning bluffs of northeastern Nebraska, the “Burnt Hills” of North Dakota, and White Cliffs of the Missouri in central Montana, remain one of the expedition’s most famous geological observations.

Dubbed “Ship Rock” on Clark’s route map, but now known as Monumental Rock, this distinct outcropping of the Lower Monumental Member of the Saddle Mountains Basalt is located on the south bank of the Snake River in Walla Walla County, Washington, just upriver of Lower Monumental Dam.

Columbia Gorge Waterfalls

by John W. Jengo

William Clark: “Saw 4 Cascades caused by Small Streams falling from the mountains on the Lard. Side.”

Rooster Rock at Crown Point

by John W. Jengo

The promontory of Crown Point comes to mind when Clark mentions in his notebook journal that the expedition camped “under a high projecting rock.”

Phoca (Seal) Rock

by John W. Jengo

The mid-river island identified as “Phoca” and “Seal rock” on one of William Clark’s route maps is a compact landslide block that detached from the Cape Horn headland.

Geology of The Dalles

by John W. Jengo

Over four days (22-25 October 1805) the expedition would be navigating through one of the most exciting and difficult stretches of the entire water route to the Pacific. Several outstanding geological features were noted.

Near Wallula Gap, Meriwether Lewis apparently collected an enigmatic and long-missing mineral specimen that was never documented in the expedition journals.

Columbia River Basalts

by John W. Jengo

The region of the lower Snake River and the Columbia River’s course through the Columbia Plateau and Gorge experienced volcanic activity starting some 55 million years ago, although the expedition would primarily encounter rock units of Miocene-age.

The expedition traveled out from under an ancient river channel frozen in time to a river discharging huge volumes of sediment in real time, the “quicksand river,” now known as the Sandy River.