John Thomas Evans (1770–1799), was a Welsh explorer in search of the mythic Welsh, or Madoc, Indians said to be residing in North America. The London literary society, the Gyneddigion, sponsored Evans to sail to America and find the lost tribe established by Prince Madoc—their “Lost Brothers in America.”[1]W. Raymond Wood, Prologue to Lewis & Clark: The Mackay and Evans Expedition (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2003), 43,97.

By 1795, Evans was in the employ of Scotsman James Mackay. Both were from St. Louis, both were naturalized Spanish citizens, and both had been hired by the Spanish government to represent Spain’s right to displace British trading companies and maintain control of commerce in Upper Louisiana.

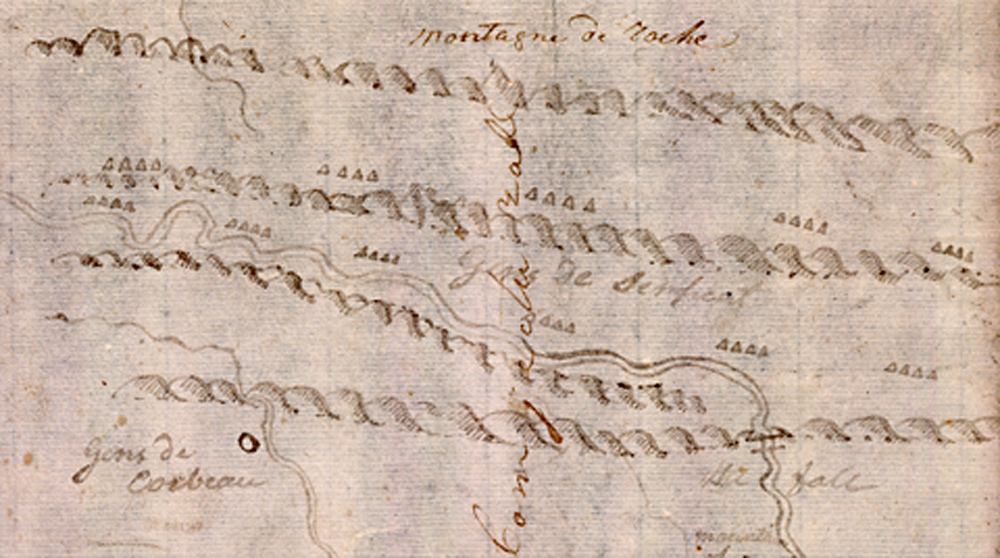

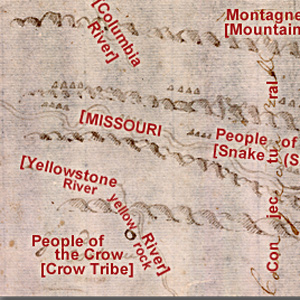

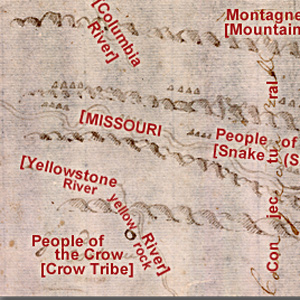

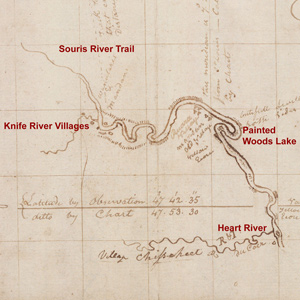

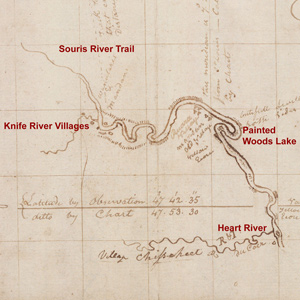

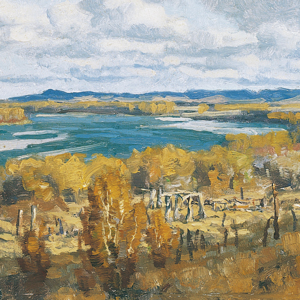

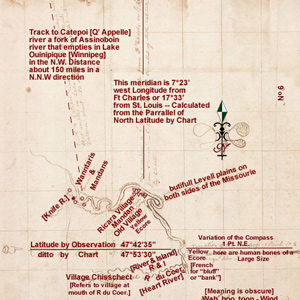

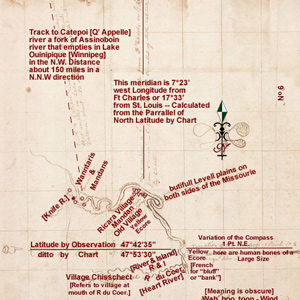

John Evans proceeded up the Missouri River under Mackay’s orders to explore all the way to the Pacific Ocean. He got no farther than the Mandan and Hidatsa villages at the Knife River, but there he queried his Indian hosts about Western geography and learned of a waterfall “of an astonishing height” about six hundred miles to the west of the Mandans, the Great Falls of the Missouri. He subsequently provided Mackay with six detailed maps of the river from Fort Charles to the Knife River, and a seventh from the Knife River to the Rockies based on Indian information he had gathered. It is certain the captains had his seven maps, the most significant outcome of the Mackay-Evans Expedition.

The Mythic Madoc Indians continues to thrive in popular culture, bringing renewed interest in John Evans’ history. On his return to St. Louis, he renounces the entire idea of the there being Welsh Indians:

[15 July 1797]

Dear Sir,

. . . . .

Thus having explored and charted the Missurie for 1800 miles and by my Communications with the Inians this side of the Pacific Ocean from 35 to 49 Degrees of Latitude, I am able to inform you that there is no such People as the Welsh Indians, and you will be so kind as to satisfie my friends as to that doubtfull Question.

I am, Dear Sir, with due respect, your very humble servant, J. Thomas Evans.[2]John Evans to Samuel Jones, Papers of Dr. Samuel Jones, Pennepek Baptist Church, Lower Dublin Township, Mrs. Irving H. McKesson Collection of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; reprinted from Williams, … Continue reading

Of course, those seeking to turn myths into historical evidence will only think the Dr. Jones letter is a fake. More rightfully, John Evans should be remembered for his significant contributions to the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

Related Pages

This Arikara leader rode upriver with the expedition in the weeks that followed to negotiate a peace settlement with the Mandan. In the spring of 1805 he went down river with the barge to St. Louis. After a series of delays, he went to Washington, DC, to meet with President Jefferson.

The Mandans

by Kristopher K. Townsend

After the 1781 smallpox epidemic, the Mandan had moved into to a more defensible position in two villages immediately south of the Hidatsa at the Knife River. The Mandan-Hidatsa alliance had developed many years prior, and the two tribes previously shared their large hunting territory to the west.

Lewis’s Branding Iron

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Lewis may have had this branding iron custom-made before he left the East, perhaps at Harpers Ferry, although there is no mention of it in existing records. Such tools commonly were used for marking wooden packing crates and barrels, and on leather bags, until the early 20th century.

Fur Trade after the Expedition

by W. Raymond Wood

The Louisiana Purchase and the lure of its beaver population led to a veritable flood of traders and trappers moving toward the Upper Missouri and the Northern Rocky Mountains and the slow abandonment of the overland trade in the United States by Canadian and British interests.

The Indian Vocabularies

by Bob Saindon

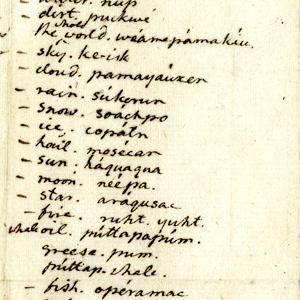

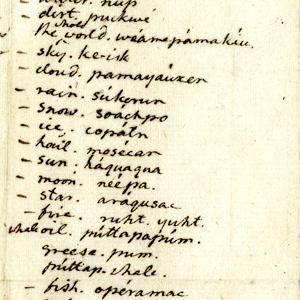

Due to the many unfortunate events which followed Lewis’s death, in 1809, the Indian vocabularies the captains had carefully collected are now lost, and were never made available to the public.

Clark evidently began compiling a map of the Northern Rockies after meeting with Hugh Heney at Fort Mandan on 18 December 1804, and continued adding information acquired from other traders, as well as from Indians. The reality, he would find, was much different.

The Corps of Discovery had been, as James Ronda phrased it, “only the latest in a long series of traders and travelers” to visit the tribes living along the Missouri. The Mandans had been visited in 1738 by la Vérendrye from his base on the Assiniboine River.

December 28, 1803

Mackay and Evans journals

At Wood River, Clark reports “nothing remarkable to day”. Elsewhere, Lewis tells President Jefferson that he has a census of Louisiana and journals and maps from explorers John Evans and James Mackay.

January 22, 1804

A snowy day

On or near this snowy day at winter camp across from the mouth of the Missouri, Clark estimates they will cross the Rocky Mountains this coming November. Lewis continues working in Cahokia and St. Louis.

On 16 June 1804, Clark took a long walk through a “butifull extensive Prarie” to look for an old fort on Evans’s map, built by the French thereabouts more than eighty years earlier. The party spent three days here making new oars and ropes, and hunting.

September 14, 1804

Pronghorn and jackrabbit

As the men move the boats up the Missouri below present Oacoma, South Dakota, Clark kills a pronghorn, and Pvt. Shields kills a white-tailed jackrabbit. In his natural history notes, Lewis describes each.

October 20, 1804

Pursuits and escapes

Below the Heart River Clark in present North Dakota, Clark sees On-a-Slant, a Mandan village abandoned due to Sioux attacks. Cruzatte wounds a grizzly and bison, and the unlucky hunter is chased by both.

November 18, 1804

Blackcat visits

At Fort Mandan, Black Cat’s wife brings as much corn as she can carry. Blackcat tells the captains that the Mandans have decided to continue with the Canada-based traders rather than St. Louis.

Clark’s Fort Mandan Maps

by Joseph A. Mussulman

While wintering over at Fort Mandan, Clark made a series of maps based on Indian information and previous traders such as John Evans and François Larocque.

Shortly before noon on the 13 June 1805, Lewis’s ears “were saluted with the agreeable sound of a fall of water,” which “soon began to make a roaring too tremendious to be mistaken for any cause short of the great falls of the Missouri.”

Notes

| ↑1 | W. Raymond Wood, Prologue to Lewis & Clark: The Mackay and Evans Expedition (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2003), 43,97. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | John Evans to Samuel Jones, Papers of Dr. Samuel Jones, Pennepek Baptist Church, Lower Dublin Township, Mrs. Irving H. McKesson Collection of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; reprinted from Williams, “John Evans’s Mission,” 600–601, quoted in Wood, 190–91. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.