The “Sokulks”

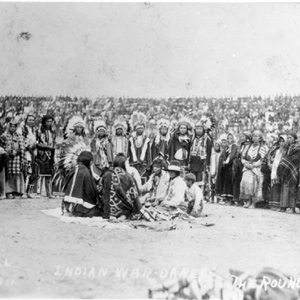

Lewis and Clark called them “Sokulks” but they were ‘river people’ from the Sahaptin wána (river) and pam (people). Wanapam is an alternate spelling.[1]William Bright, Native American Placenames of the United States (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2004), 545. When the dugouts pulled up to the spit of land between the Snake and Columbia Rivers, they were shown by nearby villagers where to camp. Shortly after, Clark reported “about 200 men Singing and beeting on their drums Stick and keeping time to the musik, they formed a half circle around us and Sung for Some time.” Because the expedition’s Nez Perce guides had traveled ahead to prepare the villagers for the expedition’s arrival, the group may have included many Sahaptin peoples other than the Wanapums and Yakamas noted by Clark.

Last Wanapum Prophet

In the figure, Puck Hyah Toot stands by a flag previously owned by his uncle Smohalla (Smowhalla, Dreamer). The latter revived the Washani Religion and Washat dance and blended his own contributions to start a revivalist religion popular among the Columbia Plateau peoples. The religion’s most famous follower was Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce. Puck Hyat Toot carried the movement into the twentieth century.

The flag has a six-sided star and was flown only when a Washat dance was in progress. Behind is the Columbia River at Priest Rapids, so named for the priest living there, Smohalla, by traders traveling with David Thompson in 1811. Priest Rapids are now inundated behind Priest Rapids Dam.[2]Click Relander, Drummer and Dreamers (Caxton Printers, Ltd., 1986), 29, plate 9; Helen H. Shuster, Handbook of North American Indians: Plateau Vol. 12, ed. Deward E. Walker, Jr. (Washington, D.C.: … Continue reading

Selected Encounters

Flag Presentations

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Lewis and Clark usually distributed flags at councils with the chiefs and headmen of the tribes they encountered—one flag for each tribe or independent band.

October 16, 1805

A musical welcome

The paddlers negotiate the last of the Snake River rapids and the expedition arrives at the Columbia River. Soon after, they are given a musical welcome from a large group of Yakamas and Wanapums.

October 17, 1805

Snake and Columbia observations

At the confluence of the Columbia and Snake rivers, Lewis takes vocabularies from the Wanapum and Yakama speakers, and hunters are sent out to collect sage grouse specimens. Clark explores the Yakama River.

October 18, 1805

Down the Columbia

At the mouth of the Snake, the captains council with the Wanapums and Yakamas. Late in the day, the expedition heads down the Columbia and camps below the Twin Sisters in Wallula Gap.

Notes

| ↑1 | William Bright, Native American Placenames of the United States (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2004), 545. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Click Relander, Drummer and Dreamers (Caxton Printers, Ltd., 1986), 29, plate 9; Helen H. Shuster, Handbook of North American Indians: Plateau Vol. 12, ed. Deward E. Walker, Jr. (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1998), 349. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.