The desire to return to St. Louis motivates the paddlers as they head up the Columbia River. Across from the Sandy River, they stop to hunt and dry meat. They explore the Willamette and Sandy hoping that one of them is the fabled river that comes from California.

Below Celilo Falls, they begin trading for horses and by the time they reach the Walla Walla River, they have enough horses to take the overland Travois Trail back to the Snake River. They then continue by horse up the Clearwater River.

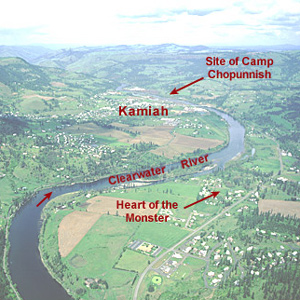

At Kamiah in present Idaho, they establish a “Long Camp” among the Nez Perce to wait for mountain snows to melt. Sgt. Ordway takes a side trip to the Salmon and Snake rivers where some Nez Perce fishers are catching salmon.

After five weeks sharing with the Nez Perce, they head to the mountain trails that will take them to the land of the buffalo.

The Wahkiakums

by Kristopher K. Townsend

The Wahkiakums exemplify the complexities encountered when trying to classify Chinookan peoples. Linguistically, they spoke the Upper Chinookan Clackamas dialect. Culturally, they were related to the Lower Chinookan Clatsops and Chinooks proper. They resided primarily along the north side of the Columbia between Grays Bay and Cathlamet, Washington.

The Wascos and Wishrams

by Barbara Fifer

At The Dalles lived Upper Chinookan people, the Wishrams on the Columbia’s north (Washington) side—and their allies the Wascos on the south (Oregon) side—who were the main masters of the regional trading center. The Lewis and Clark Expedition encamped on the north side.

The Palouses

At the time of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, the Palouses had coalesced around four primary villages on the lower Snake River: Penewawa, Almota, Wawaiwai, and Palus. Lewis and Clark estimated their population as 2,300 which included Northern Nez Perce.

The Cowlitz

The Cowlitz proper were Southwestern Coast Salish peoples living mainly along the Cowlitz River. The people were blenders. Those living among the Chinookan Skilloots intermarried and may have been indistinguishable when the expedition passed the “Cow-e-lis’-kee” River.

The Multnomahs

by Kristopher K. Townsend

When interviewing William Clark and George Shannon to prepare his condensation of the expedition journals, Nicholas Biddle wrote in his notes that “The Multnomah nation is placed on the Wappatoe Island opposite the mouth of the Multh. river and the inlet which forms the island. . . . the neighbors speak of the Multnomah nations as great &c.”

The Yakamas

The Yakama’s first Euro-American contact was the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1805. The captains named the people Chim’-nah-pum’ which was the name of the village at the mouth of the Yakima River.

The Umatillas

After emerging from the Wallula Gap on 19 October 1805, Clark came across some Umatillas hiding in their lodges, and he committed a serious faux pas by entering without permission.

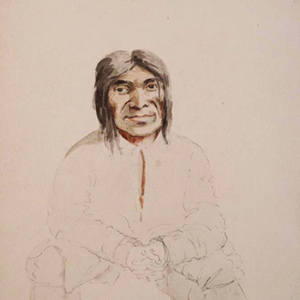

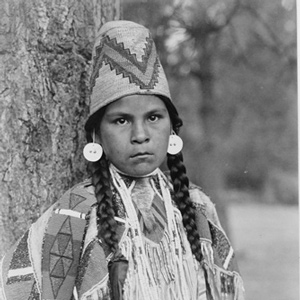

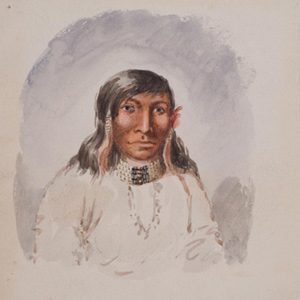

The Nez Perce

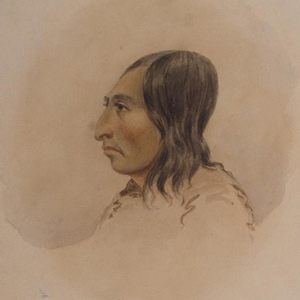

by Kristopher K. Townsend

First encountered September 1805 when John Colter met them on Lolo Creek near Travelers’ Rest, they would remain with the expedition in one way or another until 25 October 1805 saying their goodbyes at Rock Fort at The Dalles of the Columbia River. They were together again between 23 April 1806 and 4 July 1806, the expedition’s longest period of contact with any Native American Nation.

The Walla Wallas

Walla Wallas, sometimes Waluulapam and sometimes on this site as Walula, are a Sahaptin-speaking indigenous people that lived primarily along their namesake river. There has been disagreement among historians regarding the nation’s etymology.

The Coeur d’Alenes

The Skitswish, or Coeur d’Alenes, often visited the Nez Perces on the Clearwater River. Three met the captains at the mouth of Colter’s Creek.

The Clackamases

by Kristopher K. Townsend

The Clackamas people had about twelve villages south of the Columbia River, along the Clackamas River, and at Willamette Falls in what is now Portland and Oregon City. They spoke the Clackamas dialect as did nearby Multnomahs and Skilloots. On 2 April 1806, two young Clackamas men came to “Provision Camp” near present-day Washougal and sketched a map of the Willamette River, the mouth of which the expedition captains had failed to find.

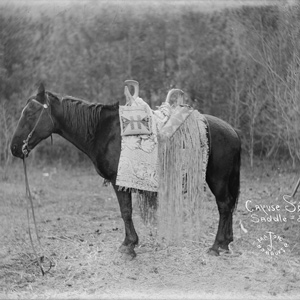

The Cayuses

by Kristopher K. Townsend

Clark’s name for the Cayuse, the Ye-E-al-po Nation, may have been his phonetic spelling of the Nez Perce name for them—Waiilatpu. The people are noted for their namesake horses and the 1847 murders at the Whitman Mission.

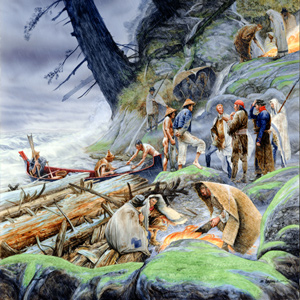

The Watlalas

by Kristopher K. Townsend

Watlala was the name of a key Upper Chinookan village at the Cascades of the Columbia. The name has been extended by many to mean the tribe more often called the Cascades. The captains called them the Shahala, meaning ‘those upriver.’ The natural constriction of the river provided the people with a fishery and a good measure of control over those who traveled up and down the river. As a result, the Cascade Clahclellah village which the expedition visited on 31 October 1805 and 9 April 1806 was a major trade center before and during white contact.

The Clatsops

by Kristopher K. Townsend

The creek where Coyote built his legendary house—today’s Neacoxie Creek—flows north to south bisecting nearly the length of the Clatsop Plain. A village at the estuary created by the ocean, Neacoxie Creek and the larger Necanicum River is Ne-ah-coxie Village. Nearby were three other Clatsop villages, and for a short time, a salt works built by soldiers from the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

The Chinooks

by Kristopher K. Townsend

Today, Chinook often refers to the politically united Lower Chinook, Clatsops, Willapas, Wahkiakums, and Kathlamets. To Lewis and Clark, the Chinook were the people living on the north side of the Columbia River’s estuary. When Lewis and Clark met them, the people of Baker Bay had been trading with European ships for more than a decade.

The Kathlamets

by Kristopher K. Townsend

The expedition journalists recorded several encounters with the Kathlamets, or Cathlamets, during their stay at the Pacific coast during the 1805–06 winter. On 11 November 1805, while hunkered down in a “dismal nitch” on the north side of the Columbia, a canoe “loaded with fish of Salmon Spes. Called Red Charr” pulled to shore. After buying 13 sockeye, Clark marveled.

The Chilluckittequaws

White Salmon and Smock-shops

by Kristopher K. Townsend

Wind Mountain was at the western extent of a series of Upper Chinookan villages called by Lewis and Clark the “Chilluckkittequaw nation.” Apparently, when asked for a tribal name, the captains were given the word for ‘he pointed at me’. Chilluckittequaw was adopted as their name a century later by early ethnographer Frederick Hodge. Between Wind Mountain and Hood River, nine villages have been identified, some overlapping with Klickitats

The Skilloots

by Kristopher K. Townsend

The Skilloot were an Upper Chinookan group that spoke the Clackamas dialect of the Chinookan language. They were located on both sides of the Columbia River above and below the mouth of the Cowlitz. At first, the captains applied the name over a much wider area, perhaps misinterpreting a similar expression meaning ‘look at him!’. Cape Horn, a few miles east of Washougal, was named sqúlips, and could be the origin of the tribe’s name.

The Teninos

At the time of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, the Teninos lived on the north side of the Columbia River and controlled key fishing areas on the river’s south side. Tenino was a small village at Five Mile Rapids above The Dalles of the Columbia.

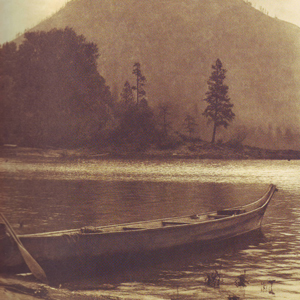

Up the Columbia

Heading home

by Barbara Fifer, Joseph A. Mussulman

Homeward bound in April 1806, the Lewis and Clark Expedition traveled through the Columbia Gorge and pitched camps on its north side. Their passage was tense and unpleasant, with Indians taking small goods regularly.

Synopsis Part 5

Fort Clatsop to St. Louis

by Harry W. Fritz

On 23 March 1806, once again battling the rising spring runoff, as it had each of the two previous years on the Missouri, the Corps of Discovery started up the Columbia River towards home.

Finding the Willamette

Filling in the blank

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Islands had hidden it from view on the westbound trip, but early on 2 April 1806 some Indians visiting their camp happened to mention it. Clark picked six of his soldiers, hired an Indian guide, and went back to see it.

Keffekill at Lake Lewis

A missing mineral specimen

by John W. Jengo

Near Wallula Gap, Meriwether Lewis apparently collected an enigmatic and long-missing mineral specimen that was never documented in the expedition journals.

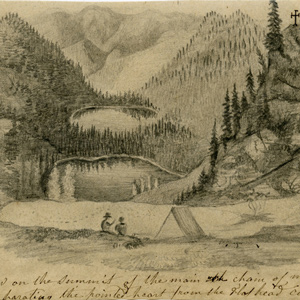

Long Camp

Five weeks with the "Chopunnish"

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Upon its return from the Pacific coast in the spring of 1806, the expedition camped on the Clearwater River near present-day Kamiah from 14 May 1806 until 10 June 1806, waiting for the snow to melt on the crest of the Bitterroot Mountains.

Long Camp Observations

25 May–9 June 1806

by Robert N. Bergantino

An analysis of Lewis’s celestial observations made during their stay at Long Camp near present-day Kamiah, Idaho.

The Salmon and Snake Villages

Side trip

by Joseph A. Mussulman

When the captains saw Nez Perces with several fresh chinook salmon, “fat and fine,” which the Indians said came from “Lewis’s River,” known today as the Salmon River, they dispatched Sgt. John Ordway and two privates to buy some.

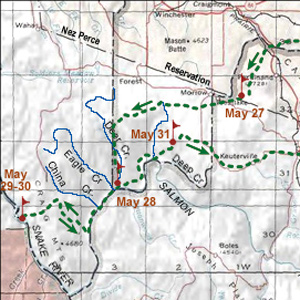

Ordway’s Fishing Trip

No mere half day

On 27 May 1806, Sergeant John Ordway, accompanied by Privates Frazer and Weiser, left Long Camp under orders to ride over to “the East branch of the Salmon River. The spring run of chinooks had not yet appeared on the Clearwater, so the three were to buy some fresh fish.

Frazer’s Razor

The enthno-history of a common object

by James P. Ronda

The comments made by Ordway and Gass about Frazer selling his razor for two Spanish dollars can tell us much about the ethno-history of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and the native peoples of the Plateau.

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.