At 4 p.m. on 7 April 1805, the permanent party heads their six canoes and two pirogues up the Missouri toward the Rocky Mountain barrier. At the same moment, Corp. Warfington and a small crew accompanied by Too Né’s delegation bound for a meeting with President Jefferson head downriver in the barge.

The Missouri River reaches it most northern position flowing from the Great Falls of the Missouri across present Montana and North Dakota. Moving through this stretch, the expedition passes the Yellowstone, Milk, Poplar, and Musselshell rivers. In the Upper Missouri River Breaks, the journalists describe both “scenes of barrenness and desolation” and “seens of visionary inchantment”.

At the mouth of the Marias, they come to a river they did not expect. They are unsure which fork is the true Missouri. After ten days exploring each, the captains decide to take the left fork.

Lewis scouts ahead to find the Falls of the Missouri that they are expecting. Sacagawea becomes dangerously ill and travels with Clark and the boats until they can go no farther—below present Belt Creek.

If the expedition is to be successful, Sacagawea will need gain her health, and the heavy boats will need to be carted around not one, but several waterfalls on a long and difficult portage.

The Assiniboines

by Kristopher K. Townsend

The Assiniboines were nomadic hunter-gatherers roaming primarily along the rivers in Saskatchewan and western Manitoba. They often dropped south into present-day Montana and North Dakota, especially in their role as middle-men between the English trading companies and the Hidatsas to the south.

The Atsinas

by Kristopher K. Townsend

Today, they are called the Atsina or Gros Ventre, but their names in the historical literature—Big Bellies, Gros Ventre and Minnetares—cause confusion even to this day. The expedition never met them, but their presence affected the expedition in several ways.

Synopsis Part 2

Fort Mandan to the Marias River

by Harry W. Fritz

Near the mouth of the Knife, in late October 1804, the expedition settled down for the winter. After the river ice broke up, the keelboat left for St. Louis and six new dugout canoes headed the opposite direction, up the Missouri river.

The Fort Union Formation

by Robert N. Bergantino

Today it is a high and dry plain, but sixty million years ago it was a shallow saucer in the earth’s crust, filled with warm, steamy tropical jungles. That rich, dense vegetation would, over some millions of years, become a huge, complex deposit of lignite.

Mouth of the Yellowstone

When Captain Lewis arrived at the mouth of the great river in late April 1805, he saw a “rich, delightful land, broken into valleys and meadows, and well supplied with wood and water.”

Fort Union

Upper Missouri developers

by Joseph A. Mussulman

This is where, in 1828, John Jacob Astor’s American Fur Company built Fort Union, which remained the axis of Indian-American commerce on the Upper Missouri until the late 1860s.

Culbertson, Montana

Abundance

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Somewhere in this vicinity, on 29 April 1805, Lewis shot his first grizzly bear and promptly began his detailed study of the fascinating species. Other game was astonishingly abundant, too.

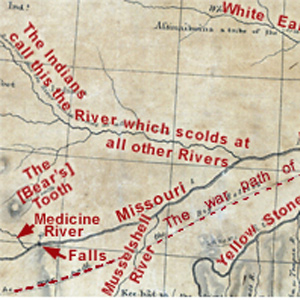

The Milk River

The river which scolds all others?

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Creeping down the nearly imperceptible slope of the northern high plains, this is the stream Lewis and Clark described as possessing a peculiar whiteness, being about the colour of a cup of tea with the admixture of a tablespoonfull of milk.

Fort Peck Dam

Varied landscape

by Joseph A. Mussulman

“The countrey on the North Side of the Missouri is one of the handsomest plains we have yet Seen on the river,” Clark declared. Lewis described the ragged badlands on the south side as “high broken hills….”

Charbonneau’s Prayer

Accident in the white pirogue

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Charbonneau’s ultimate test of faith came as a boatman, on a day when he was at the helm of the white pirogue. After a sudden gust of wind, he panicked and turned the boat sideways to the wind, turning the boat over.

Fort Peck Lake

Close calls

by Joseph A. Mussulman

The fourteenth of May was a day of close calls. With no time to reload their weapons, the grizzly bear hunters flung them aside and leaped over a twenty-foot-high bank into the river.

The Musselshell River

Sharp curve

by Joseph A. Mussulman

On 19 May 1805, the expedition camped on the east side of the neck, or “gouge,” in the Missouri River where the Musselshell River joins it. It had been an exhausting day.

Charles M. Russell NWR

Missouri Breaks

by Joseph A. Mussulman

The wind against them again on 25 May 1805, the Corps had to tow their boats with ropes. Lewis observed, “the water run with great violence, and compelled us in some instances to double our force in order to get a perorogue or canoe by them.”

Into the Breaks

Fred Robinson Bridge to Judith Landing

by Joseph A. Mussulman

In 1804-5-6 Lewis and Clark called all rough or relatively precipitous elevations, wherever they saw them, “broken” lands; the topography along this 149-mile stretch of the Wild and Scenic Missouri River was clearly the worst they had ever seen.

Geology of the Breaks

The geologic entries

by John W. Jengo

As a professional geologist and a Lewis and Clark enthusiast I’m impressed by what the captains had to say about the geology of the Upper Missouri River Breaks, as suggested by the following journal excerpts and commentary.

The Judith River

by Joseph A. Mussulman

“at the distance of 2½ miles passed a handsome river which discharged itself on the Lard. side, I walked on shore and acended this river about a mile and a half in order to examine it”

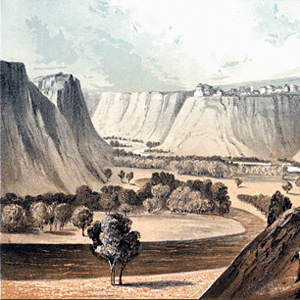

The Grand Natural Wall

"walls of tolerable workmanship"

by Joseph A. Mussulman

“As we passed on it seemed as if those seens of visionary inchantment would never have an end; for here it is too that nature presents to the view of the traveler vast ranges of walls of tolerable workmanship.”

The White Cliffs

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Under cloudy skies on the morning of 31 May 1805, the expedition “proceeded at an early hour,” and roped their flotilla of six cottonwood dugout canoes and two big pirogues into one of the most famous riverscapes on the Missouri.

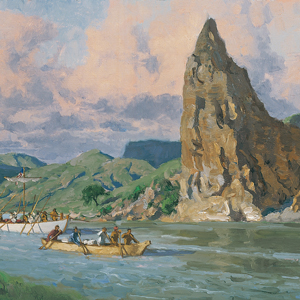

Citadel Rock

"Steep black rock"

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Clark remarked on this “high Steep black rock riseing from the waters edge” as they passed it on 31 May 1805, but he did not give it a name. Citadel Rock, so called during the steamboat era for its fortress-like presence, was an igneous intrusion into a layer of sandstone.

The Teton River

Clark's "Tanzy" and Lewis's "Rose"

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Clark first called it the “Tanzey.” Apparently Lewis dubbed it Rose River, for he noted that “the wild rose which grows here in great abundance in the bottoms of all these rivers is now in full bloom, and adds not a little to the beauty of the cenery.”

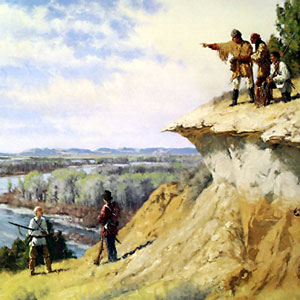

Decision Point

Marias River decision

by Joseph A. Mussulman

The two captains “strolled out to the top of the hights in the fork of these rivers,” from which they had “an extensive and most inchanting view.”

The Marias River Observations

2–10 June 1805

by Robert N. Bergantino

It was a clear night. The moon, just two days short of its first quarter, was 23° above the horizon bearing S78° W when the captains began their observations about 9:30 p.m.

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.