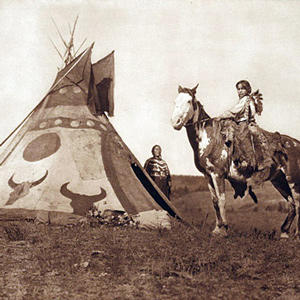

They commonly called themselves saokí•tap•ksi meaning ‘prairie people.’ The meaning ‘people with black feet’ comes from exonymns—the names given by other, external tribes. Historically, several related groups comprise the Blackfoot or Blackfeet people:

- Siksika (Blackfoot)

- Kainai or Kainah (Blood)

- Piikani (Piegan Blackfeet)

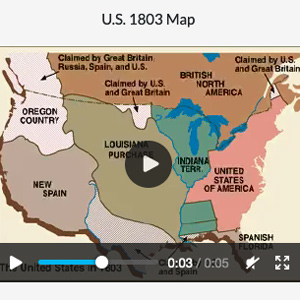

While Blackfoot is typically applied north of the 49th parallel and Blackfeet to those from the United States, linguistically they are all members of the Western division of the Algonquian language family. They also are members of the Blackfeet Confederacy which includes Atsinas, Arapahos, and Cheyennes.[1]Frederick Webb Hodge, Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico, Vol. 1 (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology, Government Printing Office, 1912), 138,570.

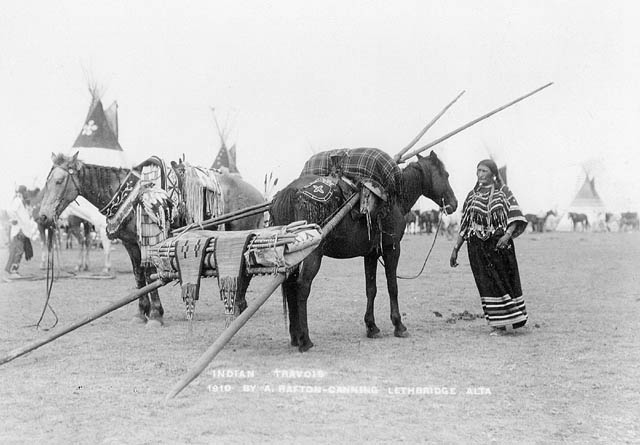

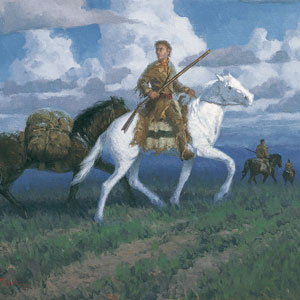

Prior to European contact, the Blackfeet had traded for horses via the Eastern Shoshone to the south and weapons and tools via the Cree to the East.[2]See on this site Indian Horses in the PNW. Thus armed and mounted, they dominated their neighbors, and after the first traders arrived, they sought to maintain that dominance.[3]Loretta Fowler and Regina Flannery, Handbook of North American Indians: Plains Vol. 15, ed. Raymond J. DeMallie (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1978), 608, 623.

At the time of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, the captains avoided encounters with Blackfeet people as the Americans’ presence would be seen as a serious threat to their dominance over other tribes in the region. Despite that, Lewis risked a trip to locate the source of the Marias River. On his way back to the Great Falls of the Missouri, he did meet a group of young Blackfeet men. For more on that encounter, see The Marias River Risk and Fight on the Two Medicine.

For many years after the expedition, traveling, trapping, and trading in Blackfeet country was unusually risky. In 1810, near the Three Forks of the Missouri, expedition members George Drouillard and John Potts were killed by Blackfeet, and John Colter made his famous run to escape death at their hands.[4]For more on this period, see Blackfeet Confederacy and American Trappers, 1806–1840 by Jay H. Buckley.

Today, there are three First Nations governments in Canada, and in the United States, the Blackfeet Nation is a federally recognized tribe residing in Northern Montana.[5]“Blackfoot Confederacy,” Wikipedia, accessed on 25 November 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blackfoot_Confederacy.

Selected Pages and Encounters

The Blackfeet Confederacy

Short tempers and long knives

by Jay H. Buckley

Next to grizzly bears and Mother Nature, the most feared enemy of American fur trappers traveling along the upper Missouri River were the Niitsítapi or Blackfeet, the “Original People” or “Prairie People.” Was that Lewis’s fault?

Montana’s Indian Country

Changes after the expedition

by Rick Newby

Beginning with the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, the U.S. government set the vast area north of the Missouri (approximately 20 million acres) aside as the “Blackfeet Hunting Ground” for the Blackfeet and other tribes—Cree, Assiniboine, Gros Ventre, and Sioux.

The Marias River Risk

"Of highest national importance"

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Why was it so important that Meriwether Lewis was willing to risk his life in a region occupied by the “Pahkees” or Minnetares, the Assiniboines, and other people whom he had been led—by their enemies, of course—to believe were “vicious and illy disposed”?

Blackfeet Songs

An interview with an elder

These songs are used in honorings, giveaways, recognition of society members, and respect for veterans. Blackfeet reporter Pelah Hoyt talked with Professor of Music Joseph Mussulman about the expedition and its music.

The Marias Massacre

My Lai on the Marias

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Some blame the ruin of the Blackfeet people on the Lewis and Clark Expedition. The story is far too complicated to be told fully in a few hundred words. Many foul deeds on both sides led up to the “the greatest slaughter of Indians ever made by U.S. troops.”

July 4, 1806

Dangerous roads

Lewis travels east on “Cokahlahishkit”—the Road to the Buffalo—along the Blackfoot River. Clark travels south up the Bitterroot River and celebrates the Fourth of July with a “Sumptious Dinner”.

July 17, 1806

Signs of danger

Between the Falls of the Missouri and the Marias River, Lewis sees signs of Indian hunters. On the Yellowstone, Clark passes an “Indian Fort”. Sgt. Ordway runs Pine Tree Rapids and Sgt. Gass waits above the falls.

July 23, 1806

Blackfeet and Crow near

At Camp Disappointment, clouds prevent Lewis from making celestial observations. Clark’s group is ready to paddle down the Yellowstone, and another detachment portages around the Falls of the Missouri.

July 25, 1806

Pompy's Tower (Pompeys Pillar)

Clark names Pompy’s Tower and then carves his name into it. At Camp Disappointment, Lewis waits one more day. At the Great Falls, the portage route is muddy. Sgt. Pryor herds horses south of the Yellowstone.

July 26, 1806

A Blackfeet interview

On the Two Medicine River, Lewis is joined by several young Blackfeet. All of Pryor’s horses are stolen, and the portage of the Great Falls of the Missouri is completed. Clark explores the Bighorn River.

July 27, 1806

Fight with the Blackfeet

Lewis has a fatal fight with the Blackfeet, Ordway paddles down the Missouri, Gass takes horses to the Teton River, Clark paddles through the Yellowstone Badlands, and Pryor is stranded without horses.

Fight on the Two Medicine

An "accedental interview"

by Joseph A. Mussulman

The Indians invited the Americans to share a campsite that night. At daybreak, despite the soldiers’ watchfulness, the Indians tried to steal the Americans’ guns and horses. That immediately erupted into a skirmish.

August 3, 1806

Clark reaches the Missouri

Clark reaches the Missouri-Yellowstone confluence and camps there to dry things out. Lewis makes seventy miles down the Missouri nearing present Fort Peck, Montana. Sgt. Pryor is still on the Yellowstone.

Notes

| ↑1 | Frederick Webb Hodge, Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico, Vol. 1 (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology, Government Printing Office, 1912), 138,570. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | See on this site Indian Horses in the PNW. |

| ↑3 | Loretta Fowler and Regina Flannery, Handbook of North American Indians: Plains Vol. 15, ed. Raymond J. DeMallie (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1978), 608, 623. |

| ↑4 | For more on this period, see Blackfeet Confederacy and American Trappers, 1806–1840 by Jay H. Buckley. |

| ↑5 | “Blackfoot Confederacy,” Wikipedia, accessed on 25 November 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blackfoot_Confederacy. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.