Watlala Village of the Cascades People

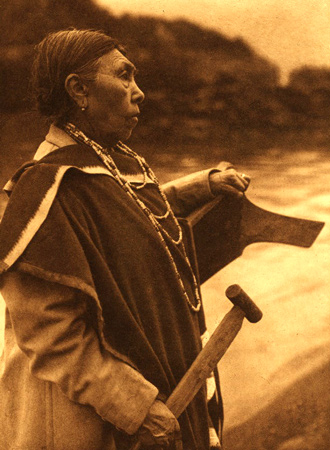

Kamagwaih – Cascade

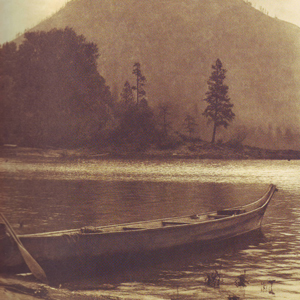

Whylick Quiuck, Virginia Miller, Tumulth’s Daughter[1]Chuck Williams, a Cascade Chinook and direct descendant of Tumulth has Virginia as Tumulth’s daughter. Other researchers say her father was Tamakoun, a different Cascade chief who met Father … Continue reading

Edward S. Curtis (1868–1952)

Courtesy Northwestern University Library, Edward S. Curtis’s “The North American Indian,” 2003. http://curtis.library.northwestern.edu/site_curtis.[2]Edward S Curtis, The North American Indian (1907-1930), vol. 8 (Cambridge, Mass.: The University Press, 1911), facing page 138.

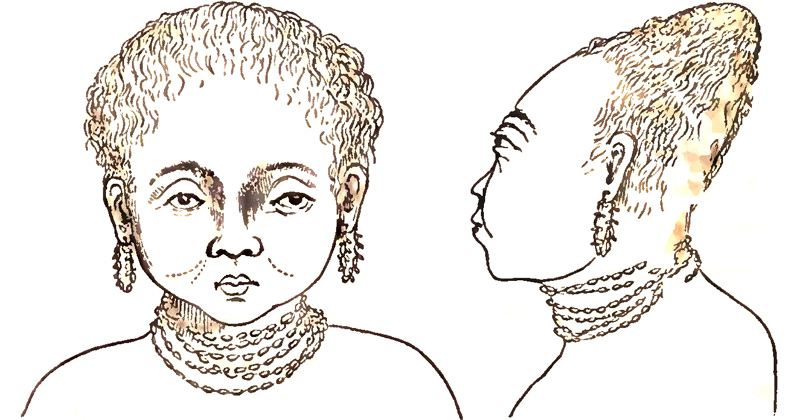

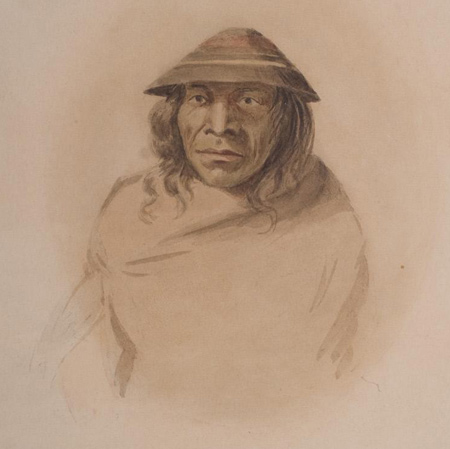

One of Paul Kane‘s subjects was Tamakoun (his To-ma-quin), a Cascade chief. Ethnographers David and Kathrine French, identify the chief’s son in an earlier sketch by Joseph Drayton, a member of the 1841 Wilkes Expedition.[3]David H. French and Katherine S. French, Handbook of North American Indians: Plateau Vol. 12, ed. Deward E. Walker, Jr. (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1998), 371–72; Kenneth R. Lister, … Continue reading Of the child, Wilkes wrote:

Mr. Drayton obtained a drawing of a child’s head that had just been released from its bandages, in order to secure its flattened head. Both the parents showed great delight at the success they had met with in effecting this distortion.[4]Charles Wilkes, The Narrative of the United States Exploring Expedition During the Years [1838–1842] (Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1845), 4:388.

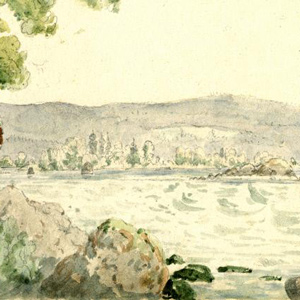

Watlala was the name of a key Upper Chinookan village at the Cascades of the Columbia. The name has been extended by many to mean the tribe more often called the Cascades. The captains called them the Shahala, meaning ‘those upriver.’[5]French and French, 375. The natural constriction of the river provided the people with a fishery and a good measure of control over those who traveled up and down the river. As a result, the Cascade Clahclellah village which the expedition visited on 31 October 1805 and 9 April 1806 was a major trade center before and during white contact.

In 1847, artist Paul Kane had time to observe and sketch several Cascade people and the submerged forest above the Cascades. He described the Cascade fishery and their method of collecting tolls from travelers:

We were engaged both days in carrying the parcels of goods across the portage, and dragging the empty boats up by lines. This is a large fishing station, and immense numbers of fish are caught by the Hudson’s Bay Company and the Cascade Indians, who congregate about here in great numbers at the fishing season, which happened at the time of our passing. They gave us a good deal of trouble and uneasiness, as it was only by the utmost vigilance that we could keep them from stealing.[6]Paul Kane, Wanderings of an Artist among the Indians of North America . . . (London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans, and Roberts, 1859), 259.

In the fall of 1805 and spring of 1806, the expedition had similar experiences with the Watlala. At that time, the tribe sold their fish not to an English trading company, but to other tribes. Forty years later saw the arrival of Oregon Trail settlers who hired the Cascades to steer their rafts through the rapids. Just a decade after that, a wooden railroad traversed the portage and steamboats on either end ferried passengers and goods along the river.

The 1855 Treaty

In 1855, Cascade leaders signed the 1855 Willamette Valley Treaty which listed the people as the “Wah-lal-la band of Tumwaters.” The treaty was ratified by Congress, and a majority of Cascades were moved to the Grand Ronde Reservation along with many other native nations from western Oregon. Others moved to the Yakama and Warm Springs reservations.

One of the treaty signers, Tumulth, was still at Watlala when Yakamas and Klickitats attacked Fort Rains in an attempt to block white trade through the Cascades of the Columbia. The Cascades maintained their innocence and did not flee when Lt. Philip Sheridan and his dragoons arrived. Sheridan held court and, according to oral tradition, if the defendant had recently fired his gun, he was declared guilty. Sheridan had Tumulth and eight other Cascades hanged. This was the beginning of the Plateau Indian War, Col. Steptoe’s defeat, and Gen. George Wright’s campaign of brutal retribution in Eastern Washington and parts of the Idaho panhandle.[7]Williams, 315–16; Donald L. Cutler, “Hang them all”: George Wright and the Plateau Indian War (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2016), 93–94.

The Cascades Today

Today, the Cascades maintain a fishery at the falls even though river is a reservoir behind Bonneville Dam. In the 1950s, the Bureau of Indian affairs declared the Grand Ronde Tribe assimilated and it was one of many Western Oregon Tribes terminated via the Western Oregon Indian Termination Act (PL 588). Many could not afford to purchase their allotments and had to move from the reservation. The federal government restored the tribe in 1983 leading to a resurgence of culture and community. Although Kiksht, the language of the Upper Chinook no longer has any speakers, the common Chinuk Wawa pigeon spoken among the diverse tribes living at the Grand Ronde Reservation has been preserved and is now taught.[8]French and French, 360; Robert H. Ruby, John A. Brown, and Cary C. Collins, A Guide to the Indian Tribes of the Pacific Northwest (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010), 379–80; David G. … Continue reading

Selected Pages and Encounters

October 31, 1805

Portaging the "Great Shute"

Clark and Pvt. Cruzatte scout the “Great Shute” at the Cascades of the Columbia, and two canoes are carried around the rapids. Clark continues down the river and sees a tall monolith—Beacon Rock.

November 1, 1805

A day with the Watlalas

Most of the men move baggage and canoes around the Cascades of the Columbia. Clark describes the Upper Chinookan Watlala People living in the area, and Lewis adds Pacific madrone to his plant collection.

November 2, 1805

Last of the rapids

Non-swimmers carry baggage, and others paddle the empty dugout canoes though the lower rapids of the Cascades of the Columbia. They pass Beacon Rock and camp below present Crown Point in Oregon.

November 4, 1805

Busy day, noisy night

Moving down the Columbia River, a Chinookan villager introduces the captains to the wapato bulb—a staple Native food. At camp near present Ridgefield, Washington, they are kept awake by noisy waterfowl.

Up the Columbia

Heading home

by Barbara Fifer, Joseph A. Mussulman

Homeward bound in April 1806, the Lewis and Clark Expedition traveled through the Columbia Gorge and pitched camps on its north side. Their passage was tense and unpleasant, with Indians taking small goods regularly.

March 30, 1806

Prospects for a settlement

As they paddle through an area dense with Multnomah and Watlala villages, they see Cascade Mountain snow peaks, fertile land, and the best prospect for a large settlement west of the Rocky Mountains.

March 31, 1806

Provision Camp

A multi-day basecamp is established to find the rumored “Waters of California” and to gather provisions. They learn that the missing river could be the as yet seen Willamette River.

April 1, 1806

Exploring the 'Quicksand' River

At Provision Camp, Pryor’s detachment explores the Quicksand River—the present Sandy in Oregon. Visiting Indians of various Nations warn of no food upriver, and no salmon for another month.

April 2, 1806

Exploring the Willamette River

Clark sets out to find the Multnomah River and at its mouth, resorts to trickery to entice Indians to trade for food. At Provision Camp, Lewis says the berries are all gone except for the Oregon grape.

April 3, 1806

Mapping the Willamette River

Clark concludes his exploration of the Willamette River and learns that a smallpox epidemic had devastated the local population. At Provision Camp, Lewis demonstrates the air gun as a defensive measure.

April 4, 1806

Hunting parties

At Provision Camp near present Washougal, Washington, the captains coordinate various hunting parties. Many “parties of the natives” visit, and Lewis takes astronomical observations.

April 8, 1806

High winds, poor hunting

At present Shepperds Dell, Oregon, wind-driven waves fill the dugout canoes with water. Lewis takes a nature walk and sees salmonberry blossoms. Late in the night, thief is caught sneaking into camp.

April 9, 1806

Beautiful waterfalls

The flotilla moves sixteen miles up the Columbia River Gorge marveling at its many beautiful waterfalls. In Washington City, the Secretary of War deals with the unexpected death of Arikara Chief Too Né.

April 11, 1806

Seaman stolen

On this wet spring day at the Cascades of the Columbia, the men tow four dugout canoes through the “big Shoote.” Hostilities ensue when a few local Indians start stealing things—even Lewis’s dog Seaman.

April 12, 1806

Lost dugout

Portaging the Cascades of the Columbia, a rope breaks and the largest dugout is lost. The men arm themselves against numerous thieves despite some of the Watlalas condemning their relations who steal.

April 13, 1806

New dugouts and dogs

With only four dangerously overloaded canoes, Lewis must buy two new dugouts from some Watlalas. He also buys some dogs for dinner at present Dog Mountain east of Stevenson, Washington.

Notes

| ↑1 | Chuck Williams, a Cascade Chinook and direct descendant of Tumulth has Virginia as Tumulth’s daughter. Other researchers say her father was Tamakoun, a different Cascade chief who met Father Blanchet in 1841 and converted to Catholicism. Chuck Williams, Chinookan Peoples of the Lower Columbia, ed. Robert T. Boyd, et al. (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2013), 315–16. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Edward S Curtis, The North American Indian (1907-1930), vol. 8 (Cambridge, Mass.: The University Press, 1911), facing page 138. |

| ↑3 | David H. French and Katherine S. French, Handbook of North American Indians: Plateau Vol. 12, ed. Deward E. Walker, Jr. (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1998), 371–72; Kenneth R. Lister, Paul Kane the Artist: Wilderness to Studio (Toronto: Royal Ontario Museum Press, 2010), 105, 154. |

| ↑4 | Charles Wilkes, The Narrative of the United States Exploring Expedition During the Years [1838–1842] (Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1845), 4:388. |

| ↑5 | French and French, 375. |

| ↑6 | Paul Kane, Wanderings of an Artist among the Indians of North America . . . (London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans, and Roberts, 1859), 259. |

| ↑7 | Williams, 315–16; Donald L. Cutler, “Hang them all”: George Wright and the Plateau Indian War (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2016), 93–94. |

| ↑8 | French and French, 360; Robert H. Ruby, John A. Brown, and Cary C. Collins, A Guide to the Indian Tribes of the Pacific Northwest (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010), 379–80; David G. Lewis, et al., Chinookan Peoples . . ., 308–09; The Chinuk Wawa Dictionary Project, Chinuk Wawa: As Our Elders Teach Us to Speak It (Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community of Oregon, 2012). |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.