Controlling the great mart at The Dalles were the Wishrams on the north shore and the Wascos on the south side of the Columbia.

“Tsagiglalal, the Guardian of Nixluidix”

Edward S. Curtis (1868–1952)

Special Collections, Mansfield Library, The University of Montana, Missoula

Original size, 18.6 x 13.3 cm (c. 7-1/4 x 5-1/4 in). Sepia-toned photogravure print from The North American Indian, Vol. 8, Frontispiece

Curtis recounted the legend of Tsagiglalal, the Rock Woman:

A woman had a house where the village of Nihhluidih [Nixluidix] was later built. She was chief of all who lived in this region. That was long ago, before Coyote came up the river and changed things, and people were not yet real people. After a time coyote in his travels came to this place and asked the inhabitants if they were living well or ill. They sent him to their chief, who lived up in the rocks, where she could look down on the village and know all that was going on. Coyote climbed up to her home and asked: “What kind of living do you give these people? Do you treat them well, or are you one of those evil women?” “I am teaching them how to live well and to build good houses,” she said. “Soon the world is going to change,” he told her, “and women will no longer be chiefs. You will be stopped from being a chief.” Then he changed her into a rock, with the command, “you shall stay here and watch over the people who will live at this place, which shall be called Nihhluidih.”[1]Edward S. Curtis, The North American Indian, 20 vols. (Norwood, Massachusetts: Plimpton Press, 1911), 8:145-46.

Curtis added that the petroglyph must have been extremely old, since all those dwelling in the village believed that even long ago, the oldest of the old thought of it only as something done by Coyote. “All the people know,” he reflected, “that Tsagiglalal sees all things, for whenever they are looking up at her those large eyes are watching them.”[2]Ibid., 46n.

The Dalles in 1805 and 1806

At The Dalles lived Upper Chinookan people, the Wishrams on the Columbia’s north (Washington) side—and their allies the Wascos on the south (Oregon) side—who were the main masters of the regional trading center. The Lewis and Clark Expedition encamped on the north side, in Wishram territory, when they passed through The Dalles in both 1805 and 1806. The captains believed that the people called themselves “Echelutes,” which modern linguists say actually was i-c-xl˙it, identifying the speaker as a resident of Nixluidix, the Wishram’s main village and trading spot.[3]By regional custom, native people identified themselves by their villages rather than tribes; tribal names came later, mostly bestowed by whites. Chinookan Peoples identified themselves by villages rather than tribes.

The expedition camped by Nixluidix on 24 October 1805, without learning its name, at the head of the Long Narrows; Clark’s advance trading party returned 16 April 1806, with Lewis and the main command arriving on the 19th; the united Corps portaged the Long Narrows and left the village the following day.

The Wishrams and other Chinookans, the captains complained, helped themselves to tomahawks, knives, spoons, and other items left out. Historian James P. Ronda explains these acts as the Indians’ way of delivering a two-part message. First, the Corps obviously had more things than they needed and could well pay for services rendered, such as advice and demonstrations of how to run the rapids and where the portages lay. Second, the Wishram expected the takings to result in a meeting, a council in the captains’ terms, where the latter could “offer respect and attention to the trading lords of the Columbia.”[4]James P. Ronda, Lewis and Clark Among the Indians (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1984), 171-72. Notably, when Clark pushed to purchase horses (still in relatively short supply here, see Indian Horses in the PNW) for three days in the spring of 1806, many portable items disappeared from camp. This pattern, however, was common during visits to many other Chinookan villages beyond Nixluidix.

Masters of the Mart

It had been only two decades since whites had found their way into the lower Columbia and inserted themselves into the regional trading network, purchasing furs there with muskets, ammunition, beads, and metal tools and ornaments. The news had arrived in an alarming manner when Lower Chinookans, including Chief Concomly,[5]A chief of the Chinook proper on the Columbia estuary’s Baker Bay, Concomly, also known as Comcomly, visited Lewis and some of his men at Point Ellice and Station Camp on 17 November 1805. canoed to upstream villages (defended solely by bows and arrows), demanded cut-rate prices, and then fired their new muskets to reject unacceptable deals. But no previous whites had come in to trade at The Dalles, challenging the Wishrams’ supremacy face to face. Guns were still scarce, as were horses that were being traded into the area from the Nez Perce and other tribes to the southeast.

The trade in goods would continue comfortably until 1813. In 1825, the Hudson’s Bay Company of Great Britain opened Fort Vancouver. It sat across the Columbia and a bit upstream from the mouth of the Willamette River, precursor to the city of Vancouver, Washington. Agriculturally self-supporting, the fort was administrative headquarters for Hudson’s Bay trappers from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific coast. Its proximity was the beginning of the end for The Dalles’ trading mart.

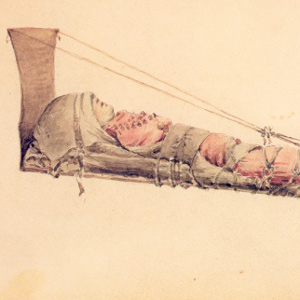

For Lack of an Interpreter

The Lewis and Clark Expedition, with no Chinookan speakers in their company, managed only minimal communication with the Wishrams. At Fort Clatsop on 1 March 1806, Lewis noted that the Tillamooks held slaves, which were adopted into families and treated like relatives. He did not learn that Chinookan custom allowed killing slaves to accompany their late master into the afterlife, or that slaves could also own slaves. While they noted Chinookan head flattening, they did not learn that only the upper of three or four castes were privileged to perform this beautifying practice and that it was forbidden to slaves. Many slaves were sold at The Dalles, where Chinookan people favored those captured a long distance away, likely in northern California, which made them less liable to try an escape.

The captains also never traded with women or learned that such was possible, or discovered that among some Chinookans women could be selected as chiefs, in a culture where each chief had a specific sphere of responsibility. They did comment that work duties were more evenly distributed between the genders around Fort Clatsop than what they had seen on the Great Plains.

Treaty and Reservation

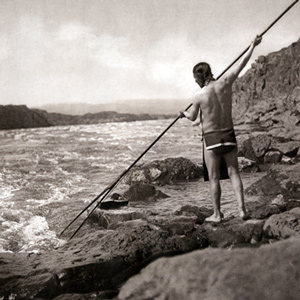

“Wishram Maid”

Edward S. Curtis (1910)

Special Collections, Mansfield Library, The University of Montana, Missoula.

Photogravure print from The North American Indian, Vol. 8, Plate 284.

Edward Curtis’s caption for this photo reads: “Clad in her deerskin dress of the plains and her basketry hat of the coast, the girl pauses on the grim lava rocks above The Dalles, looking out across the thundering rapids, perhaps observing the activities of her friends in the village Wasko.” Indians west of the Rockies abandoned the practice of flattening their babies’ heads after about 1850.

After fur trading posts run by British and American companies multiplied throughout the greater “Oregon country,” with free traders also circulating among Indian settlements, Christian missionaries followed, bringing a new religion, classroom education, and a different form of medical care.

White farm families began homesteading central Washington lands in the early 1850s, moving east from the Willamette Valley. In 1855, two years after Washington Territory was created, its governor Isaac I. Stevens negotiated the Treaty of Yakima, which consolidated the Wishrams and thirteen other tribes and bands, including Chinookan, Sahaptian, and Salishan speakers. The Wishrams resisted the U.S. government’s plan for them to move onto the Yakima Indian Reservation, which is headquartered at Toppenish, Washington. When finally they did move there, they were assimilated into the consolidated tribes, which include the Yakamas and Palouses. The government’s final act in the generations-long campaign to eliminate native life-ways was the flooding of nearly all of the traditional Wishram fishing sites on the Columbia with the completion of The Dalles Dam in 1957.

Selected Pages and Encounters

Life’s Cycle at the Dalles

by Barbara Fifer

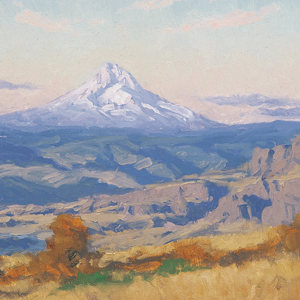

From the Columbia Plateau to the river’s mouth, people followed a yearly cycle for fishing, hunting, and harvesting wild foods. In the summer, people from many Sahaptin and Chinookan tribes visited The Dalles to trade and socialize.

October 22, 1805

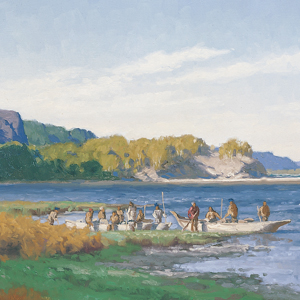

Falls of the Columbia

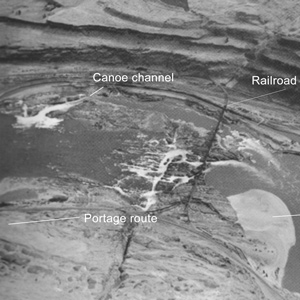

The expedition arrives at the Falls of the Columbia. With the help of some Wishram villagers, they portage their baggage along the northern shore. Others scout the channel that the canoes will navigate.

Celilo Falls

Great mart of the west

by Barbara Fifer

The Corps of Discovery reached a many-faceted barrier, Celilo Falls, which required a portage. The falls proved to be the beginning of fifty-some river miles that also held The Short and Long Narrows (jointly called The Dalles), and ended with the lengthy Cascades of the Columbia.

October 23, 1805

Lining Horseshoe Bend

The men line the heavy dugout canoes down the Horseshoe Bend of Celilo Falls while Lewis trades their smallest dugout, a hatchet, and a few trinkets for a Chinook-style canoe. Clark shoots at a sea otter.

October 24, 1805

Running the Short Narrows

The dugout canoes are safely run down the Short Narrows of the Columbia astonishing the local onlookers. Below the narrows, the expedition encounters their first Chinookan-speaking People.

The Short and Long Narrows

A bad whorl and suck

by Barbara Fifer

Here the Columbia was “an agitated gut Swelling, boiling & whirling in every direction.” Even so, Cruzatte and Clark agreed that they could run the canoes through.

October 25, 1805

A "bad whorl & Suck"

The expedition’s most valuable cargo is carried around the Long Narrows of the Columbia, and then the best paddlers run the canoes. At present The Dalles, Oregon, Fort Rock Camp is established.

October 26, 1805

Refuge at Fort Rock

At Fort Rock in present The Dalles, Oregon, two chiefs and fifteen warriors cross the river to visit and share food. They are given peace medals and other gifts, and York dances to the fiddle.

October 27, 1805

Sahaptin v. Chinookan

Sgt. Gass notices visitors with flattened heads, and the captains compare languages and customs of the Sahaptin and Chinookan Peoples living above and below The Dalles of the Columbia.

October 28, 1805

Columbia River headwinds

The expedition sets out from Fort Rock but is soon stopped by headwinds. The captains visit nearby Chilluckittequaws where Clark sees goods acquired from British trade ships and superior Chinookan canoes.

January 13, 1806

Out of candles

At Fort Clatsop near present Astoria, Oregon, elk tallow is rendered to make new candles, and Lewis finds that elk do not have enough fat. He also describes the ship trade among the area’s Nations.

Up the Columbia

Heading home

by Barbara Fifer, Joseph A. Mussulman

Homeward bound in April 1806, the Lewis and Clark Expedition traveled through the Columbia Gorge and pitched camps on its north side. Their passage was tense and unpleasant, with Indians taking small goods regularly.

April 1, 1806

Exploring the 'Quicksand' River

At Provision Camp, Pryor’s detachment explores the Quicksand River—the present Sandy in Oregon. Visiting Indians of various Nations warn of no food upriver, and no salmon for another month.

April 9, 1806

Beautiful waterfalls

The flotilla moves sixteen miles up the Columbia River Gorge marveling at its many beautiful waterfalls. In Washington City, the Secretary of War deals with the unexpected death of Arikara Chief Too Né.

April 15, 1806

Return to Fort Rock

While paddling up the Columbia, the 33 members see many horses but are unsuccessful in trading for any. They encamp at Fort Rock at present The Dalles, Oregon. Lewis prepares four plant specimens.

April 16, 1806

"Great Mart of all this Country"

Clark crosses the river to trade for horses and calls The Dalles of the Columbia the “Great Mart of all this Country.” At Fort Rock, the men make saddles, Lewis botanizes, and Cruzatte plays the fiddle.

April 17, 1806

A struggle to buy horses

At the Wishram villages on the north side of Celilo Falls, Clark and Charbonneau struggle to buy horses. At Fort Rock, Lewis remarks on the rich verdure and prepares several plant specimens.

April 19, 1806

Portaging the Long Narrows

All hands help portage the Long Narrows of the Columbia River. The last big kettles are traded for horses, and the Indians celebrate the start of the spring salmon run. Clark moves up to a Tenino village.

April 20, 1806

Six stolen tomahawks

Working at separate villages at Celilo Falls, the captains have difficulty buying more horses and even lose one. After six tomahawks are stolen, Lewis orders all Indians away from his camp.

April 21, 1806

Several severe blows

When items are stolen from his camp, Lewis gives an Indian “several severe blows” and then threatens to kill and burn the entire village. After portaging Celilo Falls, they proceed on by horse and canoe.

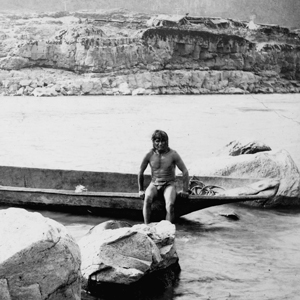

Drying Salmon

As documented by Edward Curtis

by Barbara Fifer

As documented by Edward Curtis

Photographer Edward Curtis himself described the processes pictured here. “In the preparation of this article of food the salmon was beheaded and gutted, and with a sharp knife the two halves were separated from the backbone and the skin.”

Notes

| ↑1 | Edward S. Curtis, The North American Indian, 20 vols. (Norwood, Massachusetts: Plimpton Press, 1911), 8:145-46. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Ibid., 46n. |

| ↑3 | By regional custom, native people identified themselves by their villages rather than tribes; tribal names came later, mostly bestowed by whites. |

| ↑4 | James P. Ronda, Lewis and Clark Among the Indians (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1984), 171-72. |

| ↑5 | A chief of the Chinook proper on the Columbia estuary’s Baker Bay, Concomly, also known as Comcomly, visited Lewis and some of his men at Point Ellice and Station Camp on 17 November 1805. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.