Sharitarish (Wicked Chief). Pawnee tribe

by Charles Bird King (1785–1862)

Height: 44.6 cm (17.5 in); Width: 35.1 cm (13.8 in). Courtesy The White House Historical Association, 1962.394.2.

Sharitarish represented the Chawi, or Grand Pawnees, in a delegation visiting United States President James Monroe in 1822. During that trip, he posed for portraitist Charles Bird King. He was the son of Characterish, who persuaded Facundo Melgares to abandon his attempt to stop the Lewis and Clark Expedition in September 1806 and confiscate all their possessions.

Although Clark referred to the Pawnee often and included them in the “Estimate of the Eastern Indians,” the journals do not document any face-to-face encounters. They did meet another Caddoan-speaking nation—the Arikaras—and Clark initially, and mistakenly, called those people Pawnee.

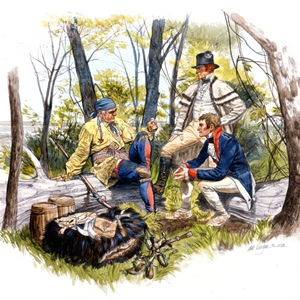

During the Lewis and Clark Expedition, the Pawnees had several significant encounters with large Spanish military parties intent on arresting Meriwether Lewis and his men. In the first, leader Pedro Vial reported that the Americans were passing out large gifts and taking Spanish peace medals and Indian commissions. He warned the people that they “still do not know the Americans but in the future they will.”[1]Diario de Dn. Pedro Vial a la nacion Panana, Santa Fe, 23 November 1804, SpAGI (Aud. Guad.398) fol. 3v-4, as translated and cited in Cook, Flood Tide of Empire, 463. Vial’s second excursion was disrupted by a Loup or Skiri Pawnee ambush and he reported that the Pawnees were “in complete agreement and commerce with the Americans.”[2]Real Alencaster to Commandant General Salcedo, Santa Fe, 4 January 1806, NmSRC – State Record Center and Archives, Santa Fe New Mexico (Span. Arch. 1942). Trans. in Loomis and Nasatir, Pedro Vial … Continue reading. In September 1806, a Spanish expedition led by Lieutenant Facundo Melgares was about 140 miles west of the Missouri River as Lewis and Clark’s men were descending the Missouri. An interception was possible, but Pawnee Chief Characterish, talked Melgares out of pursuing the matter any further. For more, see Spanish Opposition.

Through most if their history, the nation did not have a single name, but rather identified themselves as one of four separate bands:

- Skiri (Panimaha or Loup)

- Chawi (Grand)

- Kitkahahki (Republican)

- Pitahawirate (Tappage)[3]Douglas R. Parks, Handbook of North American Indians: Plains Vol. 13, ed. Raymond J. DeMallie (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 2001), 515.

Related Pages

May 27, 1804

Gasconade River

The flotilla meets two trading parties coming down from Omaha and Osage villages. At evening camp near the mouth of the Gasconade River in present Missouri, arms and ammunition are inspected.

June 14, 1804

Gobbling snakes

The morning is foggy as the boats leave the Grand River, and they make only eight miles up the Missouri. They meet four traders loaded with furs, and Drouillard hears snakes that gobble like turkeys.

July 14, 1804

Sudden storm

When they encounter a sudden storm, the men jump into the water to save the boats. An elk is wounded, and Lewis’s dog, Seaman, joins the chase. They encamp southwest of present Langdon, Missouri.

July 20, 1804

Drouillard is sick

The expedition passes Water-which-Cries and Waubonsie creeks along the present Nebraska and Iowa border. Lead hunter George Drouillard is sick, and Lewis collects two specimens of clover.

July 21, 1804

Passing the Platte

At midday, the boats arrive at the mouth of the Platte where they remark on the sandy river’s effect on the Missouri. Before continuing, the captains take a pirogue one mile up the Platte.

July 23, 1804

Searching for Otoes

George Drouillard and Pierre Cruzatte are sent to find the Otoes and invite them to council at White Catfish Camp near present Bellevue, Nebraska. A flag is hoisted as a signal.

July 30, 1804

Council Bluff arrival

The expedition arrives at a bluff at present Fort Atkinson, Nebraska where they intend hold a council with the Otoes. Pvt. J. Field kills a badger, and Lewis preserves it as his first zoological specimen.

August 3, 1804

The Otoe council

Most of the day is spent exchanging speeches, gifts, and knowledge with the Otoes and Missourias on Council Bluff at present Fort Atkinson, Nebraska. Then, the boats travel six miles up the Missouri.

August 4, 1804

Moses Reed is missing

The expedition travels 15 miles and encamps southwest of present Modale, Iowa. The captains record yesterday’s speech to the Otoes, and Pvt. Moses Reed, who left to retrieve his knife, does not return.

January 4, 1806

Across the Clatsop Plain

Sgt. Gass and Pvt. Shannon travel through the marshes and dunes of the Clatsop Plain on their way to the salt makers’ camp. At Fort Clatsop, Lewis describes Clatsop views on material goods.

September 10, 1806

News of Zebulon Pike

Fur traders heading up the river tell the captains that Zebulon Pike is leading an expedition to the source of the Arkansas River. They end the day near present Bean Lake, Missouri.

September 12, 1806

Given up for dead

At present St. Joseph, Missouri, the captains modify orders given to Pierre Dorion and Joseph Gravelines. An old military companion, Robert McClellan, says that they have all been given up for dead.

September 16, 1806

A young trader

Moving down the Missouri, they question a young trader—likely Joseph Robidoux Jr.—who lacks a properly signed license. They end the day near present Waverly, Missouri 52 miles closer to home.

September 25, 1806

Eighteen toasts

After storing botanical and zoological specimens in Pierre Chouteau’s St. Louis warehouse, the captains attend a ball. At Christy’s Tavern, eighteen toasts are given in honor of the “Missouri expedition”.

Notes

| ↑1 | Diario de Dn. Pedro Vial a la nacion Panana, Santa Fe, 23 November 1804, SpAGI (Aud. Guad.398) fol. 3v-4, as translated and cited in Cook, Flood Tide of Empire, 463. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Real Alencaster to Commandant General Salcedo, Santa Fe, 4 January 1806, NmSRC – State Record Center and Archives, Santa Fe New Mexico (Span. Arch. 1942). Trans. in Loomis and Nasatir, Pedro Vial and the Roads to Santa Fe, 442. |

| ↑3 | Douglas R. Parks, Handbook of North American Indians: Plains Vol. 13, ed. Raymond J. DeMallie (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 2001), 515. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.