In Synopsis Part 2, they winter with the Mandan before leaving in canoes up the Missouri River’s northern reach. When they reach the Marias River at Decision Point they have difficulty deciding which river to follow.

Fort Mandan Winter

Charbonneau and Sacagawea

On 4 November 1804, an independent trader named Toussaint Charbonneau, who had lived among the Hidatsas for several years, offered the captains his services as an interpreter. He was unpredictable and unreliable—”a man of no particular merit,” Meriwether Lewis was to remark later, though William Clark was somewhat more tolerant. Charbonneau’s principal asset was the wife he proposed to bring along, Sacagawea. (Her name is also sometimes spelled, and pronounced, Sakakawea or Sacajawea.[1]“Sacagawea” is Clark’s phonetic transliteration of her Hidatsa name, which he and Lewis invariably spelled with what they clearly meant to sound with a hard g in the third syllable. … Continue reading) She was a Lemhi Shoshone girl,[2]The Lemhi Shoshone band belonged to the Northern division of the Shoshone nation. Early EuroAmerican traders, including those Lewis and Clark met during their winter at Fort Mandan, called the … Continue reading perhaps 12 years old, who had been abducted from her tribe’s hunting camp by Hidatsa raiders near the Three Forks of the Missouri about four years before. It has been a persistent American legend that she was the expedition’s indispensable guide, and as such she has been the subject of more commemorative sculptures and paintings (See Faces of Sacagawea) than any other woman in American history, many of them showing her “pointing the way.”

Bitter Cold

It was cold at Fort Mandan that winter, sometimes more than 40 degrees below zero. Hunting expeditions courted danger, especially if they stayed out overnight. The Indians amazed Lewis and Clark; they dressed lightly and carried only one buffalo skin for a blanket. Members of the expedition helped the natives hunt for food, repaired tools, and treated frostbite and illnesses. They participated in ceremonial dances and other activities.

Not everything went smoothly. The captains were unable to prevent an Arikara raid on the Mandans, intertribal jealousy among the river tribes, and a bit of commercial jostling. But there were no major flare-ups.

At Fort Mandan on a sub-zero February day in 1805, Sacagawea gave birth to a son. The fact that only one man died during the hazard-filled voyage is no less remarkable than that little Jean Baptiste Charbonneau survived, not two years old at expedition’s end. From that auspicious beginning the child, later nicknamed “Pomp” by someone in the party, was to enjoy a long and varied career as a frontiersman in the white man’s West.

Sacagawea’s Roles

Although Sacagawea’s role has often been debated, there is nothing in the expedition’s journals to even hint that she guided the Corps of Discovery to the Pacific Ocean and back. The facts are before us; there is little or nothing to debate. But in no way does that diminish either the importance or the drama of her participation. At the outset the captains preferred her over Charbonneau’s other current wife because Sacagawea was a Shoshone. They envisioned a need to secure horses from her tribe for the portage from the Missouri’s sources to the headwaters of the Columbia River, so her presence might have made those negotiations easier. Yet Lewis did not even include her in his own reconnaissance detail that made the initial contact with her people.

She had been on seasonal buffalo-hunting trips from her Lemhi valley home to the Three Forks of the Missouri and the prairies of Crow country, but nearly all of the territory the expedition went through was foreign to her. Clark once called her an “interpretess,” but she spoke only Hidatsa, and one dialect of Shoshone. Nevertheless, when the Corps of Discovery approached her homeland, her recognition of some key landmarks “cheered the spirits of the party.” The land that Lewis and Clark explored was anything but a pristine wilderness. It was laced with Indian “roads,” as the captains termed them, and there were several critical junctions where a wrong turn could have led to considerable inconvenience, if not tragic consequences. Thus Captain Clark readily acknowledged her “great service . . . as a pilot” through the Big Hole and Gallatin valleys in July of 1806—two widely separated places that she happened to be familiar with. Occasionally she brought the captains edible plants and natural medicaments to help resolve minor problems. At more critical times, her mere presence was enough to convince surprised strangers of the expedition’s peaceful motives, and that was of incalculable value. Of equal importance, on the rare occasions when a Shoshone-speaking person was encountered among non-Shoshone tribes or bands, she was an indispensable link in the chain of translators leading to and from the captains.

By all of these means together, Sacagawea was what the American mythologist Joseph Campbell (1904-1987) might have called a “spirit guide.” She was a guardian figure of mysterious birth and uncertain destiny who, often without being asked, provided her heroes with the advice and assistance they needed in order to cope with some of the dragon forces they encountered. To the Corps of Discovery she was, in the poet Dante’s words, “the living fount of hope.”[3]Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces (New York: MJF Books, 1949), 69-74.

The Missouri’s Northern Reach

Near the end of March, the river-ice broke up. The men readied the barge (called the ‘boat’ or ‘barge’ but never the ‘keelboat’) for its return to St. Louis, with zoological, botanical, geological, and ethnological specimens and artifacts collected up to that point. Letters, maps, and other reports went to President Jefferson, and Secretary of War Henry Dearborn. Six new dugout canoes, each about thirty feet long and up to three feet wide, were carved from cottonwood logs. At four o’clock on the afternoon of 7 April 1805, the two parties set out in opposite directions.

“The high country on either side of the river,” they wrote, was “one vast plain, intirely destitute of timber,” extending “back as far as the eye can reach.” Across these plains swept violent winds, stirring up waves, blowing dust and sand, bringing at times the rain, snow, ice and fog of spring on the high plains. One week after leaving Fort Mandan they passed the highest point on the Missouri River that any Euro-American had ever reached. Confronting strong, shifting winds, collapsing riverbanks, and capricious currents, they proceeded on.

At the Yellowstone

On 25 April 1805, ranging ahead of the rest of the party, Lewis and his big, handsome Newfoundland dog, Seaman, along with four of the men, arrived at the mouth of the Yellowstone—or “Roche Jaune”—River. The Indians had told them about it, and the captains foresaw that it might become, for a short time at least, a key landmark in the geographical, political, and commercial topography of the Northwest.

Central Montana

Westward the terrain changed. Central Montana, they noted, was “truly a desert barren country.” Clark couldn’t imagine that the part of it he could see could ever be settled; it was deficient in water and timber, and was too steep to be tilled. Much of that territory now lies submerged under the waters of the Fort Peck Lake, but some of it remains unchanged along the Upper Missouri River Breaks, especially the 40-mile stretch now called the White Cliffs. “A most romantic appearance,” rhapsodized Lewis, as his imagination perceived “a thousand grotesque figures,” “the remains or ruins of eligant buildings,” and other “seens of visionary inchantment.” Lewis also was excited by his first glimpse, on 26 May 1805, of the distant Rocky Mountains, feeling “a secret pleasure” in finding himself so near the head of “the heretofore conceived boundless Missouri.”

Ascending the mighty, muddy Missouri at a rate of up to twenty-five miles on good days, the expedition’s journalists remarked on the rolling, treeless Great Plains grasslands, the weather and the river, and always the profusion of game. “We can scarcely cast our eyes in any direction,” wrote Lewis,”without perceiving deer Elk Buffaloe or Antelopes [pronghorn].”

There were increasingly numerous, and threatening, grizzly bears, which Lewis and Clark usually called “white bears.” Bighorn sheep, wolves, coyotes, and beavers were abundant, as were geese, ducks, sagles and swans. The Corps grew fat on the fat of the land.

Marias River Decision

At the Marias River

Produced by Joseph Mussulman

Sah cah gah, we a our Indian woman verry Sick I blead her, we deturmined to assend the South fork, and one of us, Capt. Lewis or My self to go by land as far as the Snow mountains S. 20° W. and examine the river & Countrey Course & to be Certain of our assending the proper river, Capt Lewis inclines to go by land on this expedition, according Selects 4 men . . . to accompany him

–William Clark

For more on Sacagawea’s illness, see Sulphur Springs.

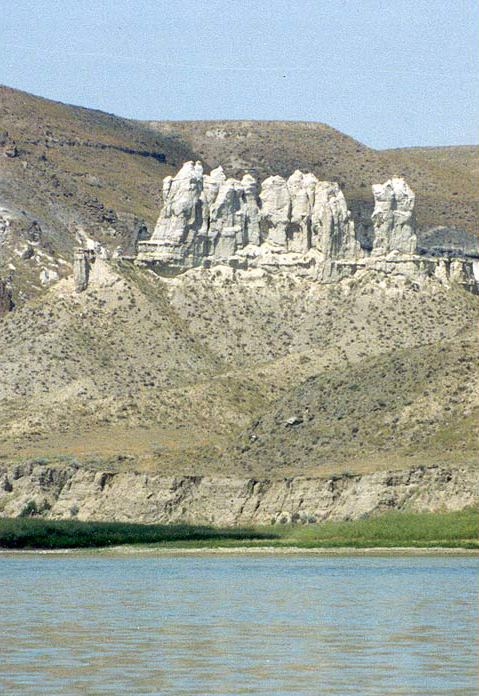

Lower Marias River

View north

© 2000, Jim Wark, Airphoto

Copies of Jim Wark’s aerial photos of the Lewis and Clark Trail

are available from Air Photo.

In this photo of the lower Marias River, taken by Jim Wark in July 1999, the water looks relatively clear, especially in the shallows around the sandbars. During the first week in June 1805, however, this was the river that challenged the Corps’ “cogitating faculties” because, as Lewis conceded, it apparently gave to the Missouri “the colouring matter and character which is retained from hence to the gulph of Mexico.” Indeed, he reassured himself that it had “every appearance of the Missouri below except as to size.” In other words, it was muddy then. And it’s still brownish today above the reservoir, Lake Elwell, before the silt settles out behind Tiber Dam.

For an extensive treatment of the land of the Marias River, see The Golden Triangle. For more aerial photos of the trail, See Lewis & Clark by Air.

Thomas Jefferson, more concerned over relations with the Spanish to the south and west of Louisiana Territory, told Lewis to learn all he could about the southern tributaries of the Missouri. “The Northern waters,” he avowed, “are less to be enquired after.” Yet one of those “northern waters” presented the expedition with a serious dilemma. On 2 June 1805, they arrived at a major fork in the river, in north-central Montana, an estimated 465 river miles upstream from the mouth of the Yellowstone. It shouldn’t have been there. No Indian informant had mentioned it. There was not even a hint of it from anybody. Yet it posed the most significant geographical question of the entire expedition. Which of these rivers was the Missouri?

The issue was fraught with danger. They needed to reach the Rockies, find the Shoshone Indians, get some horses, portage to the head of the Columbia, and reach the Pacific before winter closed in.

To choose the wrong route would consume twice the time it would take to correct the mistake, and would, Lewis declared, not only lose them the whole of the present travel season, but “would probably so dishearten the party that it might defeat the expedition altogether.” Most of the men were thoroughly convinced that the river Lewis was to call Maria’s, after his cousin, Maria Wood, was the main river, but the captains reasoned differently. In the first place, the one major northern tributary they’d heard of, the one the Indians called “the river that scolds at all others,” which they took to be the Milk River, was nearly 300 miles behind them. Second, the Marias River was muddy, but a river draining the Rocky Mountains should be clear. Finally, the Marias flowed in from the north, whereas the true Missouri was supposed to turn southwest, toward mountains they already could see. Hunches, however, were insufficient bases for this momentous decision.

Accordingly, the captains sent search parties up both rivers. When the results proved inconclusive, they set out to see for themselves. Clark went forty-five miles up the Missouri, found that it ran swift and true to the west of south, and returned persuaded. Lewis went nearly eighty miles up the Marias, confirmed that it headed from too much to the north for their route to the Pacific, and made his way back. The captains’ findings represented the triumph of field observation over hypothetical image; they corrected their maps and, sure of themselves, chose the true Missouri.[4]For more, see Along the Northern Reach, Decision Point and Lewis on the Marias.

Notes

| ↑1 | “Sacagawea” is Clark’s phonetic transliteration of her Hidatsa name, which he and Lewis invariably spelled with what they clearly meant to sound with a hard g in the third syllable. In English the name means “Bird Woman.” Whether it was a Hidatsa translation of her Shoshone name is not known. If she was only 12 when she was carried off from her peoples’ hunting camp, she might not yet have had a permanent name. The Hidatsas pronounce both the c and the g in the captains’ Sacagawea with a throaty, aspirate k, and they spell it that way—Sakakawea. The third version of the name was the invention of Nicholas Biddle, who edited the captains’ journals for publication in 1814. For some unknown reason he replaced the captains’ hard g with a soft g and spelled it with its phonetic equivalent, j. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The Lemhi Shoshone band belonged to the Northern division of the Shoshone nation. Early EuroAmerican traders, including those Lewis and Clark met during their winter at Fort Mandan, called the Shoshones “Snake” Indians, perhaps from the gesture by which they were identified in Plains Sign Language. |

| ↑3 | Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces (New York: MJF Books, 1949), 69-74. |

| ↑4 | For more, see Along the Northern Reach, Decision Point and Lewis on the Marias. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.