On the morning of 5 May 1805, the Corps of Discovery was ascending the Missouri River in what is now eastern Montana. Meriwether Lewis, as he usually did, was walking on shore while the rest of the party made its way upriver in pirogues and dugout canoes. It was a “fine morning,” Lewis would later write in his journal, and the country was “beatifull in the extreme,” filled with “a great quantity of game . . . feeding in every direction” on the shortgrass prairie. Lewis the born naturalist was in his element. In a passage that continues for well over a thousand words, he discusses the physiology, behavior, and other characteristics of the wild-life around him—geese, buffalo, elk, pronghorn antelopes, grizzly bears, coyotes, and wolves. The wolf of the plains, he tells us, is a bit smaller than the type found in eastern woodlands, with shorter legs and a coat that varies from blackish-brown to creamy white. Wolf packs were ubiquitous as they followed their prey and culled the weak: “we scarcely see a gang of buffaloe without observing a parsel of those faithfull shepherds on their skirts in readiness to take care of the mamed & wounded.”[2]Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition, 13 volumes (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001), 4:111–113.

Buffalo Hunt (cropped)

Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library. “Buffalo hunt. White wolves attacking a buffalo bull.”[3]New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed October 21, 2019. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-dbf1-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.

At the time of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, the gray or timber wolf (Canis lupus) was common in the northern regions of what would eventually become the continental United States, ranging from Maine to California and south through the plains and along the spines of the Appalachian, Rocky, and Sierra Nevada mountains. Lewis had probably encountered gray wolves in the East, although before the expedition he almost certainly would have been unfamiliar with their plains-dwelling smaller cousin, the coyote (Canis latrans), which he and Clark referred to as the prairie or “burrowing” wolf, because it lived in dens.

Entering Wolf Country

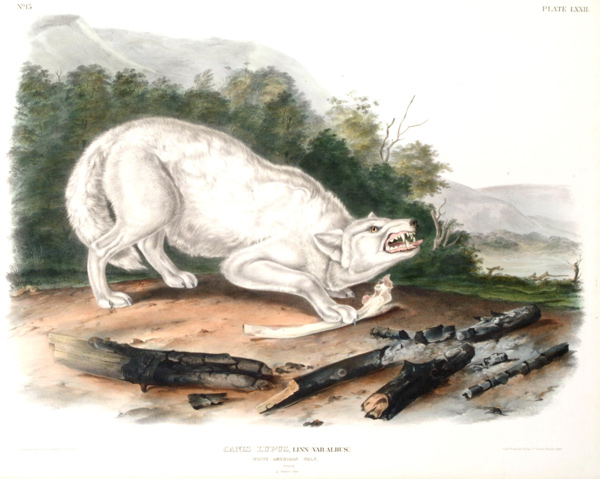

Light Wolf

John James Audubon (1785–1851)

Courtesy University of Michigan Museum of Art, Gift of J. Frederick Hoffman, 2005.[4]Canis lupus. linn. var. albus. Male. No.15, Plate LXXII. [72]

John James Audubon painted the light and dark versions of the timber wolf, which he observed in the 1840s near Fort Union, in present-day North Dakota.

The explorers entered wolf country in the early summer of 1804, some six weeks after their flotilla departed Camp River Dubois. Two were spotted from the boats on 25 June 1804, near the mouth of the Kansas River, in what is now the out-skirts of Kansas City. A hunter was quickly dispatched and shot one of them, the first of 36 wolves killed during the 28-month expedition.[5]Ibid., 11:30. Joseph Whitehouse, entry for 25 June 1804: “we saw two Wolves, on the shore; one of our Men went a shore . . . and shot one of them.” Another was shot the next day, and a wolf cub was captured alive by Joseph and Reubin Field, who wanted to keep it as a pet. They tied it up, but after three days it escaped by chewing through its rope.[6]Ibid., 10:17 (Patrick Gass, entry for 26 June 1804); 11:32 (Joseph Whitehouse); and 9:8 (John Ordway). Ordway and Whitehouse differ from Gass in recording the date of the first wolf kill as 28 June … Continue reading

Wolves remained a presence in the explorers’ lives as they continued upriver to the Mandan and Hidatsa villages, in present-day North Dakota. They encountered them frequently while in winter camp at Fort Mandan and during their ascent of the Missouri the following spring. On the outbound journey the last wolf sighting occurred at the Great Falls on July 7, 1805. Lewis and Clark would not see another wolf until a year later, on July 8, 1806, near the Great Falls, on the homeward trip.[7]Ibid., 8:97. Lewis, descending the Medicine (now Sun) River with his party, observed “a great number of deer[,] goats [antelopes] and wolves as we passed through the plains.” A little … Continue reading

In all, the journals reveal a total of 59 days in which wolves were seen. Mainly these encounters occurred in Montana and North Dakota, where the greatest concentrations of the prey on which wolves feed-bison, elk, deer, and pronghorns-were found. The number of predators an ecosystem can support depends on the quantity of game, and the reported absence of wolves in the mountains can be attributed to the relative scarcity of large herbivores.[8]Exactly why Lewis and Clark found so much game on the high plains and so little of it in the mountains can be attributed to several factors. First and foremost, game was relatively scarce in the … Continue reading Prey and predators were also scarce along the Columbia River. Writing at Fort Clatsop, Lewis states that both “large and small woolves” (i.e., gray wolves and coyotes) could be found in the open country and bordering woodlands of the Pacific coast but “are not abundant . . . because there is but little game on which for them to subsist.”[9]Moulton, 6:331. Entry for 20 February 1806. Substantially the same wording appears in Nicholas Biddle‘s compilation of Lewis and Clark’s Fort Clatsop writings on flora and fauna. Elliott … Continue reading

Hunting Strategies

Canis lupis, Black American Wolf. Male.

John James Audubon

Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library. “Canis lupus, Black American Wolf. Male. 1/3 Natural size.”[10]New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed October 21, 2019. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-7835-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.

Lewis’s observations about wolves and coyotes were the first detailed accounts of these animals in their western habitat. His descriptions, and those of the expedition’s other journalists, make fascinating reading for anyone interested in the natural world, and as a kind of historical baseline they remain important to wildlife biologists. In part, no doubt, because he was a hunter himself, Lewis was fascinated by the wolf pack’s hunting strategies. Here is his account of wolves hunting pronghorns, written in late April of 1805, three weeks after leaving Fort Mandan:

game is still very abundant we can scarcely cast our eyes in any direction without percieving deer Elk Buffaloe or Antelopes. The quantity of wolves appear to increase in the same proportion; they generally hunt in parties of six eight or ten; they kill a great number of the Antelopes at this season; the Antelopes are yet meagre and the females are big with young; the wolves take them most generally in attempting to swim the river; in this manner my dog caught one drowned it and brought it on shore; they are but clumsey swimmers, tho’ on land when in good order, they are extreemly fleet and dureable. we have frequently seen the wolves in pursuit of the Antelope in the plains; they appear to decoy a single one from a flock, and then pursue it, alturnately relieving each other untill they take it.[11]Moulton, 4:85. The location is eastern Montana, just beyond the present Montana-North Dakota border.

Patrick Gass reported on a similar technique for hunting pronghorns, or “goats,” as they were often (if erroneously) called:

The wolves in packs occasinally hunt these goats, which are too swift to be run down and taken by a single wolf. The wolves having fixed upon their intended prey and taken their stations, a part of the pack commence the chase, and running it in a circle, are at certain intervals relieved by others. In this manner they are able to run a goat down.[12]Ibid., 10:258. Entry for 27 July 1806.

On another occasion Lewis relates how:

Capt Clark informed me that he saw a large drove of buffaloe pursued by wolves today, that they at length caught a calf which was unable to keep up with the herd. the cows only defend their young so long as they are able to keep up with the herd, and seldom return any distance in surch of them.”[13]Moulton, 4:60–61. Entry for 22 April 1805. The location is north of present-day Williston, North Dakota.

Evolution Hones a Predator

When the Land Belonged to God

Charles M. Russell (1864–1926)

Courtesy Montana Historical Society, Helena, Montana.

Charles M. Russell’s painting “When the land belonged to God” shows the close relationship between buffalo herds and wolf packs.

Lewis, Gass, and Clark knew nothing about natural selection—Darwin’s The Origin of Species wouldn’t be published until 1859—but their accounts hint at the co-evolution of predator and prey that occurred over millennia on the grasslands of North America. For grazing animals such as bison, natural selection would have favored herding, which conveys the obvious advantage that comes from strength in numbers, while pronghorns have evolved their remarkable speed—they can sprint at 60 mph—to outrun predators. But wolves have evolved their own physical and mental traits to meet these challenges. They are tireless distance runners, able to chase a herd for miles on end, and for shorter distances they can dash at speeds approaching 30 miles per hour.[14]John C. McLoughlin, The Canine Clan: A New Look at Man’s Best Friend (New York: Viking Press, 1983), 62. McLoughlin expresses a wolf’s speed in metrics—45 kilometers per hour for two … Continue reading Keen-eyed, with sharp senses of hearing and smell, they are also acutely intelligent and possessed of a social instinct that enables them to hunt in a coordinated way—pressing a herd until the weakness of one of its members shows, then isolating and killing that individual. Wolves make successful kills in roughly one out of three or four attempts. When times are lean they can go several weeks without food, and when they do eat they can gorge on up to twenty pounds of meat, which they bolt down in large chunks without chewing.

Wolves have 42 teeth (ten more than humans), including dagger-like canines and specialized carnassials for shearing through bone, ligament, and muscle. This fearsome equipment comes in handy not only for taking down prey but also for feeding on carrion. Wolves aren’t picky—they will scavenge whenever the need and opportunity arise, as the explorers discovered:

Sent the others to bring in the ballance of the buffaloe meat, or at least that part which the wolves had left us, for those fellows are ever at hand and ready to partake with us the moment we kill a buffaloe; and there is no means of puting the meat out of their reach in those plains; the two men shortly after returned . . . and informed me that the wolves had devoured the greater part of the meat.[15]Moulton, 4:289. Lewis’s entry for 14 June 1805.

On a hunting trip he led out of Fort Mandan under brutal winter conditions, Clark built a log pen to protect the meat from wolves and scavenging ravens and magpies.[16]Ibid., 3:291–292. On an occasion the previous fall on the Missouri, a hunter shot a buffalo, then returned to the boats to find someone to help him butcher the meat and carry it back. To keep scavengers away he placed his hat on the carcass. While he was gone, wolves ate the meat and carried off the hat.[17]Ibid., 10:37. Patrick Gass, 8 September 1804. Gass says the wolves “carried off the hat,” but one suspects that they ate it along with the meat.

Wolves prowled the banks of the Missouri looking for an easy meal in the form of drowned buffalo. Lewis counted 27 feasting on a carcass lodged at the tip of an island above the Great Falls.[18]Ibid., 8:108. Entry for 14 July 1806. As the explorers approached the Missouri Breaks on the outbound journey, they came upon “a great many wolves” lingering at a pile of putrefying bison. The wolves had obviously been feasting for several days, for they were sated to the point of lethargy—Lewis found them “fat and extreemly gentle,” so much so that Clark was able to walk up to one and spear it with his espontoon.[19]Ibid., 4:219. Entry for 29 May 1805. Scholars debate whether these bison had been washed there by the river or killed by Indians who had driven them off a bankside cliff. See Francis Mitchell, … Continue reading

The pack that Lewis had noted feeding on a buffalo above the Great Falls engaged at night in a chorus of howling. Wolves use this signature behavior to communicate within the pack and to establish territory. It is a haunting, primeval, unworldly sound. Anyone who has listened to a pack’s eerie serenade on a wilderness night can understand the fear it provoked in our ancestors and why, in western folklore, the wolf is so often portrayed as evil. One might assume that as products of western culture, Lewis and Clark and their men would have shared this attitude. Yet the journal accounts of wolves are utterly free of this cultural prejudice.[20]Apparently, the explorers first heard wolves howling on 21 July 1804, although they did not even bother to record it at the time. Clark’s journal entry states, “a Great number of wolves … Continue reading The entries are straight-forwardly factual and nonjudgmental, even when they describe wolves filching the explorers’ meat or—as happened once—attacking them.

This incident occurred on the homeward journey. Sergeant Nathaniel Pryor was leading a party down the Yellowstone River when a wolf wandered into their campsite one night and bit him through the hand as he lay sleeping. The animal then attacked one of the other men (Richard Windsor) but was shot by George Shannon before it could do more damage.[21]Moulton, 8:285. Clark’s entry for 8 August 1806, reporting on an incident that occurred the previous 26 July 1806. This is highly aberrant behavior for healthy wolves, which seldom if ever attack humans. It is behavior more typical of a rabid wolf, but if this one had rabies, its bite miraculously failed to infect Pryor.

Expedition Wolf Kills

| Date | Number | Reference* | Location |

| 25 June 1804 | 1 | 11:30 | Jackson County, Missouri |

| 26 June 1804 | 1[22]Ordway (Moulton, 9:18) and Whitehouse (11:32) say this wolf was killed June 28. | 10:17 | Jackson County, Missouri |

| 7 July 1804 | 1 | 10:19 | Buchanan County, Missouri |

| 20 July 1804 | 1 | 2:355 | Cass County, Neb. |

| 6 September 1804 | 1 | 9:55 | Charles Mix County, South Dakota |

| 8 September 1804 | 1 | 10:37 | Boyd County, Neb. |

| 17 September 1804 | 1 | 3:82 | Lyman County, South Dakota |

| 18 September 1804 | 1 | 10:41 | Lyman County, South Dakota |

| 21 September 1804 | 1 | 3:96 | Lyman County, South Dakota |

| 20 October 1804 | 1 | 10:57 | Morton County, North Dakota |

| 29 December 1804 | 1 | 9:106 | Fort Mandan, North Dakota |

| 3 January 1805 | 2 or 3 | 10:69 | Fort Mandan, North Dakota |

| 4 January 1805 | 1 | 9:108 | Fort Mandan, North Dakota |

| 5 January 1805 | 1 | 9:108 | Fort Mandan, North Dakota |

| 7 January 1805 | 2 | 3:269 | Fort Mandan, North Dakota |

| 14 January 1805 | 1 | 9:109 | Fort Mandan, North Dakota |

| 18 January 1805 | 4 | 10:70 | Fort Mandan, North Dakota |

| 16 February 1805 | 1 | 9:116 | Fort Mandan, North Dakota |

| 8 May 1805 | 1 | 4;126 | Valley County, Montana |

| 14 May 1805 | 1 | 4:151 | Valley County, Montana |

| 20 May 1805 | 1 | 11:162–63 | Garfield or Petroleum County, Montana |

| 29 May 1805 | 1 | 4:219 | Fergus County, Montana |

| 5 July 1805 | 2 | 2:363 | Cascade County, Montana |

| 7 July 1805 | 3 | 4:365 | Cascade County, Montana |

| 8 July 1806 | 1 | 8:97 | Lewis & Clark or Cascade County, Montana |

| 15 July 1806 | 2 | 8:108 | Cascade County, Montana |

| 8 August 1806 | 1 | 8:285 | Big Horn County, Montana |

*Moulton, volume:page

Total kills: 36 or 37, depending on interpretation of journal entries for 3 January 1805.

Today’s Re-introduction

The settling of the West in the century following the Lewis and Clark Expedition saw wholesale changes to the environment. The disappearance of the great herds of buffalo, elk, and other large prey, coupled with eradication campaigns by stockmen, led to the near-total extirpation of wolves in the United States. (The adaptable coyote managed to hang on and eventually to spread well beyond its historic range.) In recent years, wolves have moved down from Canada, and wildlife managers have introduced them into Yellowstone National Park and elsewhere in the Rockies, so the West is again home to these canny predators, Lewis’s “faithfull shepherds” of the plains.

Notes

| ↑1 | Kenneth C. Walcheck, “Of Wolves and Prairie Wolves”, We Proceeded On, May 2004, Volume 30, No. 2, the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. The original, full-length article is provided at lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol30no2.pdf#page=21 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition, 13 volumes (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001), 4:111–113. |

| ↑3 | New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed October 21, 2019. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-dbf1-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99. |

| ↑4 | Canis lupus. linn. var. albus. Male. No.15, Plate LXXII. [72] |

| ↑5 | Ibid., 11:30. Joseph Whitehouse, entry for 25 June 1804: “we saw two Wolves, on the shore; one of our Men went a shore . . . and shot one of them.” |

| ↑6 | Ibid., 10:17 (Patrick Gass, entry for 26 June 1804); 11:32 (Joseph Whitehouse); and 9:8 (John Ordway). Ordway and Whitehouse differ from Gass in recording the date of the first wolf kill as 28 June 1804. |

| ↑7 | Ibid., 8:97. Lewis, descending the Medicine (now Sun) River with his party, observed “a great number of deer[,] goats [antelopes] and wolves as we passed through the plains.” A little later in this entry he reports killing “a very large and the whitest woolf I have seen.” |

| ↑8 | Exactly why Lewis and Clark found so much game on the high plains and so little of it in the mountains can be attributed to several factors. First and foremost, game was relatively scarce in the mountains because the habitat wasn’t nearly as rich as that found on the plains. The abundance of game on the plains of the upper Missouri was also due to the absence of permanent Indian settlements—tribes lived on the edge of the region and hunted there only a few months of the year, in effect treating it as a vast game preserve. One should also keep in mind that Lewis and Clark traversed the Rockies in the late summer and early fall, when most game animals (and their predators) would have been at higher elevations. Hunting pressure by the Shoshones, Nez Perces, and other resident tribes would also have contributed to the scarcity of game; this was certainly the case on the west slope of the Continental Divide and throughout the Columbia River corridor. The Columbia’s salmon runs supported a large permanent population (Lewis and Clark estimated it at 80,000) but the Indians’ diet included game as well as fish. See Paul S. Martin and Christine R. Szuter, “War Zones and Game Sinks in Lewis and Clark’s West,” Conservation Biology, February 1999 (Vol. 13, No. 1), pp. 36–45; and Ken Walcheck, “Wapiti,” We Proceeded On, August 2000, pp. 26–32. |

| ↑9 | Moulton, 6:331. Entry for 20 February 1806. Substantially the same wording appears in Nicholas Biddle‘s compilation of Lewis and Clark’s Fort Clatsop writings on flora and fauna. Elliott Coues, a distinguished naturalist who edited the 1893 edition of Biddle, offers extensive commentary in a footnote. See Elliott Coues, ed., The History of the Lewis and Clark Expedition by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, 3 volumes (New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1965; reprint of 1893 edition), 3:846. |

| ↑10 | New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed October 21, 2019. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-7835-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99. |

| ↑11 | Moulton, 4:85. The location is eastern Montana, just beyond the present Montana-North Dakota border. |

| ↑12 | Ibid., 10:258. Entry for 27 July 1806. |

| ↑13 | Moulton, 4:60–61. Entry for 22 April 1805. The location is north of present-day Williston, North Dakota. |

| ↑14 | John C. McLoughlin, The Canine Clan: A New Look at Man’s Best Friend (New York: Viking Press, 1983), 62. McLoughlin expresses a wolf’s speed in metrics—45 kilometers per hour for two kilometers—which I have converted to miles. |

| ↑15 | Moulton, 4:289. Lewis’s entry for 14 June 1805. |

| ↑16 | Ibid., 3:291–292. |

| ↑17 | Ibid., 10:37. Patrick Gass, 8 September 1804. Gass says the wolves “carried off the hat,” but one suspects that they ate it along with the meat. |

| ↑18 | Ibid., 8:108. Entry for 14 July 1806. |

| ↑19 | Ibid., 4:219. Entry for 29 May 1805. Scholars debate whether these bison had been washed there by the river or killed by Indians who had driven them off a bankside cliff. See Francis Mitchell, “Slaughter River Pishkun,” We Proceeded On, February 2004, pp. 26–34. For other journal entries on wolves’ scavenging of hunter kills, see Moulton, 3:255 (7 December 1804) and 8:208 and 211 (20 July 1806 and 23 July 1806). |

| ↑20 | Apparently, the explorers first heard wolves howling on 21 July 1804, although they did not even bother to record it at the time. Clark’s journal entry states, “a Great number of wolves about us this evening.” Later, when working with Nicholas Biddle on the latter’s paraphrase of the journals, he must have mentioned that wolves were also howling that day; Biddle rendered the entry, “A number of wolves were seen and heard around us in the evening.” Coues, 1:52. |

| ↑21 | Moulton, 8:285. Clark’s entry for 8 August 1806, reporting on an incident that occurred the previous 26 July 1806. |

| ↑22 | Ordway (Moulton, 9:18) and Whitehouse (11:32) say this wolf was killed June 28. |