Bearberry (Kinnikinnick)

Arctostaphylos uva-ursi

© 2007 by Walter Siegmund. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.

Names

The botanical designation for this storied miniature shrub is Arctostaphylos uva-ursi (L.) Spreng.[1]The bearberry’s Latin name is pronounced arc-toe-STAFF-ee-los oo-va ER-see. Arktos is Greek for “bear,” and staphyle is Greek for “a bunch of berries.” Just for good measure, uva-ursi, the designation for the species, also means “berry-of-bear,” Uva-ursi being an early generic name that was rejected by the Swedish naturalist, Carl Linnaeus when he established the principles and procedures of modern botanical nomenclature in 1753. His role in the taxonomy of the bearberry is acknowledged by the parenthetical /L./ in the plant’s full name. “Spreng.” stands for the German botanist Curt Polycarp Joachim Springel (1766–1833), who wrote the first full description of the plant.

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark sometimes called it kinnikinnick, sometimes sacacommis. The Algonquian (Delaware) word kinnikinnick, meaning “mixture”, is appropriate since the plant’s dried leaves were often mixed with tobacco, the inner barks of red osier dogwood and black chokecherry, and other plant leaves. Saccacomis–or sac • comis, sagakomi, segockimac, or segockiniac–may have been derived from a Chippewa word for “mixture”. An equally familiar name is bearberry, which first appeared in print around 1625. The plant has also borne a long lexicon of other names: bear’s bilberry, bear’s grape, raisin d’ours in France. Bear’s weed, chokerberry, chipmunk’s apple, creashak, crowberry, devil’s tobacco, Indian tobacco, hog cranberry, larb, manzanita, mealberry, mealy-plum vine, mountain box, mountain cranberry, mountain laurel, rapper-dandies, redberry, rockberry, sandberry, universe vine, upland cranberry, uvursy, whortleberry, and wild cranberry.[2]Dictionary of American Regional English (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1985– ), s.v. bearberry. CRC World Dictionary of Plant Names (4 vols., New York: CRC Press, 2000), … Continue reading Herbalists know it best as uva-ursi.

The captains’ first experience with bearberry came at Fort Mandan brought by two Northwest Company clerks. Lewis explains the etymology of saccacomis as “from the circumstance of the Clerks of those trading companies carrying the leaves of this plant in a small bag for the purpose of smokeing.” Many experienced botanists and historians believe Lewis was mistaken, owing to a similar Chippewa word. When this author mentioned saccacomis in a discussion about bearberry, his French-born friend immediately recognized the phrase from his formative years in a French military school. He explained that it referred to a bag or sack from the military commissary. The friend had no prior knowledge of bearberry making this is an innocent and uncanny corroboration of Lewis’s original etymology.[3]Further research should be conducted by a qualified linguist to test the possibility that Lewis actually gave an accurate etymology for saccacomis.

The Blackfeet Indian name for bearberry is kakahsiin; the Flathead Salish call the berries skw lsé. The Pawnee name for the whole plant is nakasis, meaning “little tree.”[4]Melvin R. Gilmore, Uses of Plants by the Indians of the Missouri River Region (1914; enlarged ed., Lincoln: University of Nebraska press, 1977), 56.

Ethnobotanical Uses

Bearberry Fruits and Leaves

© 2010 Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

This bearberry bush was growing in the Lee Creek Area between Lolo Hot Springs and Lolo Pass on 14 September, the same time of year and place the Lewis and Clark Expedition passed in 1805.

At Fort Clatsop on 25 January 1806, Lewis noticed that the fruits and berries eaten by the Lower Chinook included “a Scarlet berry about the Size of a Small Cherry,” referring to the bearberry. The berries once served as a staple food for Native Americans as well as white settlers. Indians, it is said, cooked them in salmon oil, bear fat or fish eggs, or added them to soups and stews. Boiled, they were sometimes mixed with snow for a wintertime treat.[5]Linda Kershaw, Edible & Medicinal Plants of the Rockies (Renton, Washington: Lone Pine Publishing, 2000), 90–91.

A fruit so seductively colored, and set off against such a salubrious deep green foliage, ought to taste as good as it looks. Lewis himself, evidently having sampled one, judged it “a very tasteless and insippid fruit,” but added that it was reported to taste sweeter after boiling. Blackfoot, Lower Chinook, Coeur d’Alene, Flathead Salish, and Montana Nations are among those who used the berries as a food source.[6]John C. Hellson, “Ethnobotany of the Blackfoot Indians,” National Museum of Man Mercury Series, no. 19 (Ottawa: National Museums of Canada, 1974), 101, … Continue reading Additionally, black bears, rodents, songbirds and turkeys evidently find the bright berries tasty. Blue grouse (Dendragapus obscurus) and spruce grouse (Canachites canadensis) seem especially fond of them.[7]John J. Craighead, Frank C. Craighead, Jr., and Ray J. Davis, A Field Guide to Rocky Mountain Wildflowers (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1963), 130. Deer and mountain sheep eat the leaves during fall and winter.

Medicinally, Blackfoot People used bearberry in a salve for rashes and skin sores and Cheyenne People used it in medicines for sore backs, colds, and to drive away bad spirits.[8]Hellman, 75; George Bird Grinnell, The Cheyenne Indians—Their History and Ways of Life, Vol. 2 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1972), 188, archive.org/details/cheyenneindiansv0002grin. The leaves of the bearberry, which contain two glucosides plus tannic and gallic acid, have been strong medicine since at least the thirteenth century, and perhaps long before that. They once were used for their potent astringent and diuretic effects, and are still employed by some herbalists, although with rigorous limitations.

Smoking the Leaves

Ever since the expedition’s arrival at the mouth of the Columbia River in December 1805, almost daily rains had drenched the men, soaked their baggage, and spoiled their fresh meat. The urgency of erecting a common shelter overrode nearly every other need except for all but seven non-smokers: some means of stretching their dwindling supply of Turkish tobacco. On the morning of 21 December 1805, deeming it advisable to spare some hands from the construction project, Clark:

dispatched two men to the open lands near the Ocian for Sackacome, which we make use of to mix with our tobacco to Smoke, which has an agreeable flavour.

Two Native Nations separated by a continent—the Ojibwa and Kwakiutl—reported that smoking the leaves caused a type of intoxication. The Navaho and Kayenta reported similar effects from smoking nicotiana (tobacco).[9]Daniel E. Moerman, Native American Ethnobotany (Portland, Oregon: Timber Press, 1988), 808. Bearberry appears to be an effective partner with—and substitute for—tobacco. The labor to collect and dry it was minimal when compared to other substitutes such as the inner bark of red osier dogwood, chokecherry, or alder trees.

Ground Cover

Bearberry

Arctostaphylos uva-ursi (L.) Spreng

© 2007 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Bearberry Blooms

© 2008 by Walter Siegmund. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.

On 11 April 1806, enroute back up the Columbia River at the Cascades of the Columbiaa, the captains remarked that the “Sackacommis” was in bloom. They undoubtedly saw the same plant growing west of the Bitterroot Mountains, but none of them mentioned the plant’s pretty pale-pink, waxy, urn-shaped flowers. In addition to its attractive berries and blooms, Kinnikinnick is a drought tolerant plant that stays green all year. This makes it a popular ground cover in modern landscapes. In Euro-American culture, bearberry foliage often serves as a Christmas decoration.

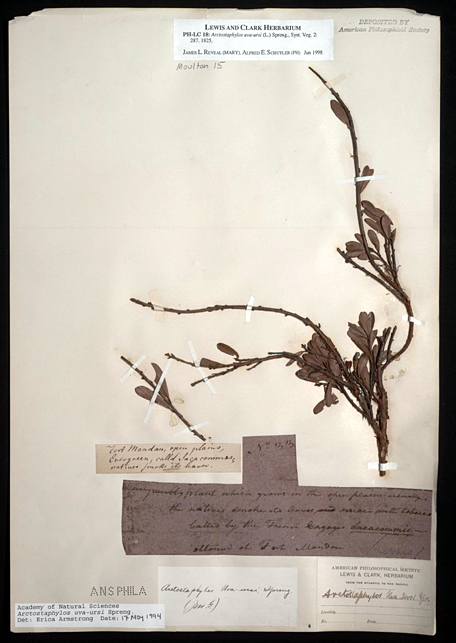

Lewis’s Specimen

At Fort Mandan on 28 February 1805, the captains received a gift of “Sacka comah” from Hugh Heney, a trader with the North West Company stationed at Fort Assiniboine, southwest of Lake Winnipeg in today’s Manitoba, Canada. Lewis sent a bearberry specimen—likely the same one gifted by Hugh Heney—to President Jefferson on the barge in spring 1805. It is item No. 33 in the list prepared by John Vaughan of the American Philosophical Society, where Jefferson sent Lewis’s specimens. The label in Lewis’s handwriting reads:

an evergreen plant which grows usually in the open plains, the natives smoke its leaves mixed with Tobacco; called by the French engagés Sacacommé. Obtained at Fort Mandan.[10]Moulton, 3:464. This information probably was taken from Lewis’ seemingly incomplete written report about his collections. During the winter of 1804-1805 Lewis drafted “A List of … Continue reading

The young German American botanist Frederick Pursh who worked with Lewis’s specimens added his own note—typical of his abridgements of Lewis’s annotations:

Fort Mandan, open plains, Evergreen, called Sacacommis, natives Smoke its leaves.

It cannot be said that Lewis discovered sacacommis, for the Connecticut Yankee Jonathan Carver (1710–1780), who explored the upper Mississippi Valley in the late 1760s, reported that:

“a weed that grows near the great lakes, in rocky places, they use in the summer season. It is called by the Indians Segockiniac, and creeps like a vine on the ground, sometimes extending to eight or ten feet. . . . These leaves, dried and powdered, they likewise mix with their tobacco.”[11]Jonathan Carver, Travels Through the Interior Parts of North-American, in the years 1766, 1767, and 1768 (London: 1778), 31. Carver was a Connecticut gentleman, shoemaker, soldier, self-taught … Continue reading

Carver did not bring back any specimens.

Lewis’s Description

At Fort Clatsop on 29 January 1806, drawing partly on information obtained at Fort Mandan, partly on his observations along the route, and finally upon the ample supply of specimens nearby, he described the plant as follows:

the growth of high dry situations, and invariably in a piney country or on it’s borders. It is generally found in the open piney woodland as on the Western side of the Rocky mountains, but in this neighbourhood we find it only in the prairies or on their borders in the more open wood lands. A very rich soil is not absolutely necessary, as a meager one frequently produces it abundantly.

The natives on this [the west] side of the Rocky mountains who can procure this berry invariably use it. To me it is a very tasteless and insippid fruit.

This shrub is an evergreen. The leaves retain their verdure most perfectly through the winter, even in the most rigid climate, as on lake Winnipic.

The root of this shrub puts forth a great number of stems which separate near the surface of the ground, each stem from the size of a small quill to that of a man’s finger. These are much more branched, the branches forming an acute angle with the stem, and all more properly procumbent than creeping, for altho’ it sometimes puts forth radicles from the stem and branches which strike obliquely into the ground, these radicles are by no means general, nor equable in their distances from each other, nor do they appear to be calculated to furnish nutriment to the plant but rather to hold the stem or branch in its place.

The bark is formed of several thin layers of a smooth, thin, brittle substance of a dark or redish brown color, easily separated from the woody stem in flakes.The leaves with rispect to their position are scattered yet closely arranged near the extremities of the twigs particularly. The leaf is about ¾ of an inch in length and about half that in width, is oval but obtusely pointed, absolutely entire, thick, smooth, firm, a deep green and slightly grooved. The leaf is supported by a small footstalk of proportionable length.

The berry is attached in an irregular and scattered manner to the small boughs among the leaves, though frequently closely arranged, but always supported by separate short and small peduncles, the insertion of which produces a slight concavity in the bury while it’s opposite side is slightly convex. The form of the berry is a spheroid, the shorter diameter being in a line with the peduncle.—This berry is apericarp, the outer coat of which is a thin, firm, tough pellicle.[12]Consistent with botanical usage in his day, Lewis used pericarp to denote a fruit. Today, the word is applied to the wall of a ripened ovary; the fruit of the bearberry is simply called a berry. … Continue reading The inner part consists of a dry mealy powder of a yellowish white color enveloping from four to six proportionably large, hard, light brown seeds, each in the form of a section of a spheroid, which figure they form when united, and are destitute of any membranous covering. The color of this [ripened] fruit is a fine scarlet.

The natives usually eat them without any preparation. The fruit ripens in September and remains on the bushes all winter. The frost appears to take no effect on it. These berries are sometimes gathered and hung in their lodges in bags where they dry without further trouble, for in their most succulent state they appear to be almost as dry as flour.—[13]Lewis almost certainly included in his “Traveling Library” Benjamin Smith Barton’s Elements of Botany. Whenever possible, definitions in these tooltip annotations are quoted … Continue reading

Notes

| ↑1 | The bearberry’s Latin name is pronounced arc-toe-STAFF-ee-los oo-va ER-see. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Dictionary of American Regional English (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1985– ), s.v. bearberry. CRC World Dictionary of Plant Names (4 vols., New York: CRC Press, 2000), 1:187. |

| ↑3 | Further research should be conducted by a qualified linguist to test the possibility that Lewis actually gave an accurate etymology for saccacomis. |

| ↑4 | Melvin R. Gilmore, Uses of Plants by the Indians of the Missouri River Region (1914; enlarged ed., Lincoln: University of Nebraska press, 1977), 56. |

| ↑5 | Linda Kershaw, Edible & Medicinal Plants of the Rockies (Renton, Washington: Lone Pine Publishing, 2000), 90–91. |

| ↑6 | John C. Hellson, “Ethnobotany of the Blackfoot Indians,” National Museum of Man Mercury Series, no. 19 (Ottawa: National Museums of Canada, 1974), 101, archive.org/details/ethnobotanyofbla0000hell; Erna Gunther, Ethnobotany of Western Washington, revised edition (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1973), 44; James Alexander Teit, “The Salishan Tribes of the Western Plateaus,” Forty-fifth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, Smithsonian Institution, 1927–1928 reprinted as Coeur d’Alene, Flathead and Okanogan Indians (Fairfield, Washington: Ye Galleon Press, 1985), 90, archive.org/details/coeurdaleneflath0000boas/; Jeff Hart, Montana Native Plants and Early Peoples (Helena: Montana Historical Society Press, 1992), 40; J.W. Blankinship, “Native Economic Plants of Montana,” Montana Agricultural College Experimental Station, Bulletin 56 (Bozeman, Montana: 1905), 7, www.google.com/books/edition/Native_Economic_Plants_of_Montana. |

| ↑7 | John J. Craighead, Frank C. Craighead, Jr., and Ray J. Davis, A Field Guide to Rocky Mountain Wildflowers (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1963), 130. |

| ↑8 | Hellman, 75; George Bird Grinnell, The Cheyenne Indians—Their History and Ways of Life, Vol. 2 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1972), 188, archive.org/details/cheyenneindiansv0002grin. |

| ↑9 | Daniel E. Moerman, Native American Ethnobotany (Portland, Oregon: Timber Press, 1988), 808. |

| ↑10 | Moulton, 3:464. This information probably was taken from Lewis’ seemingly incomplete written report about his collections. During the winter of 1804-1805 Lewis drafted “A List of specimines of plants collected by me on the Mississippi and Missouri rivers” but the extant copy lists plant specimens 1 through 32 and 100 through 108. The first 32 numbered specimens gathered by Lewis are also missing. |

| ↑11 | Jonathan Carver, Travels Through the Interior Parts of North-American, in the years 1766, 1767, and 1768 (London: 1778), 31. Carver was a Connecticut gentleman, shoemaker, soldier, self-taught surveyor and cartographer, traveler and bigamist. He held a deep conviction, shared by few others in his day, that the Mississippi River would eventually become a North American Nile or Volga, and dreamed of exploring its upper reaches. In 1766 a similarly star-crossed visionary, Major Robert Rogers, hired him to explore a portion of the territory Great Britain had gained from its victory in the French and Indian War, namely that west of Michilimackinac, a major fur-trade post at the straits that separate Lake Huron from Lake Michigan. Carver was to record its geography, describe and count its Indians, and inventory the remains of French trading posts. Rogers also dreamed of finding the Great River of the West. Rogers, beset by political misfortunes, was unable to pay Carver, and he had to abandon his expedition. In 1769 he sailed to London, hoping through appeals to the Lords Commissioners of Trade and Plantations to recoup his personal losses and resume his travels in North America. Failing in that, in 1778 he finally published his journal, which instantly became a bestseller, rocketing through some 32 printings in nine years. But its success was short-lived, for the author was accused of plagiarism, and of perpetrating a hoax. Penniless, Carver died of starvation in 1780. Not until the early 1900s was it discovered that, insofar as the charges were ever true, the guilt lay with Carver’s unscrupulous editor, who evidently had felt the explorer’s original journals needed a little extra color. Nevertheless, Carver’s Travels may have further stimulated Thomas Jefferson’s long-held ambition to sponsor an expedition to the West. See bell.lib.umn.edu/hennepin/carver.html, “The Adventures of Jonathan Carver,” by Ann K.D. Myers of the James Ford Bell Library at the University of Minnesota. Carver noted that the Chippewas mixed red-osier dogwood bark with their tobacco in wintertime, and harvested sumac bark for the same purpose at the end of September. He concluded: “By these three succedaneums the pipes of the Indians are well supplied through every season of the year; and as they are great smoakers, they are very careful in properly gathering and preparing them.” |

| ↑12 | Consistent with botanical usage in his day, Lewis used pericarp to denote a fruit. Today, the word is applied to the wall of a ripened ovary; the fruit of the bearberry is simply called a berry. Pellicle (PELL-i-kul) is Latin for skin, here the outer layer or skin of the fruit. |

| ↑13 | Lewis almost certainly included in his “Traveling Library” Benjamin Smith Barton’s Elements of Botany. Whenever possible, definitions in these tooltip annotations are quoted verbatim from that work. When needed for clarity, The Kew Plant Glossary and Plant Identification Terminology are referenced. Benjamin Smith Barton, Elements of Botany: or Outlines of the Natural History of Vegetables (Philadelphia: 1803), www.google.com/books/edition/Elements_of_Botany_Or_Outlines_of_the_Na/Hk0aAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0; Henk Beentje, The Kew Plant Glossary: An Illustrated Dictionary of Plant Terms (Royal Botanic Gardens: Kew Publishing, 2012); James G. Harris and Melinda Woolf Harris, Plant Identification Terminology: An Illustrated Glossary (Spring Lake, Utah: Spring Lake Publishing, 2009). |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.