Given President Jefferson’s directive to establish commerce, the captains worked extensively within a long-established network of North American fur trade. Part of their mission was to help establish the United States of America’s position within that industry.

The Corps of Discovery had been, as James Ronda phrased it, “only the latest in a long series of traders and travelers” to visit the tribes living along the Missouri. The Mandans had been visited in 1738 by la Vérendrye from his base on the Assiniboine River.

By the time of Lewis and Clark’s sojourn at the mouth of the Columbia River in the winter of 1805-1806, sea otter hunts and trading ventures had been at white heat for twenty years

By the time of Lewis and Clark’s sojourn at the mouth of the Columbia River in the winter of 1805-1806, sea otter hunts and trading ventures had been at white heat for twenty years

Whether they be boatmen, interpreters, traders, privates in the U.S. Army, diplomats, or cultural guides, the contribution of the French men already living in the Illinois and Louisiana region was “mission critical.”

Next to grizzly bears and Mother Nature, the most feared enemy of American fur trappers traveling along the upper Missouri River were the Niitsítapi or Blackfeet, the “Original People” or “Prairie People.” Was that Lewis’s fault?

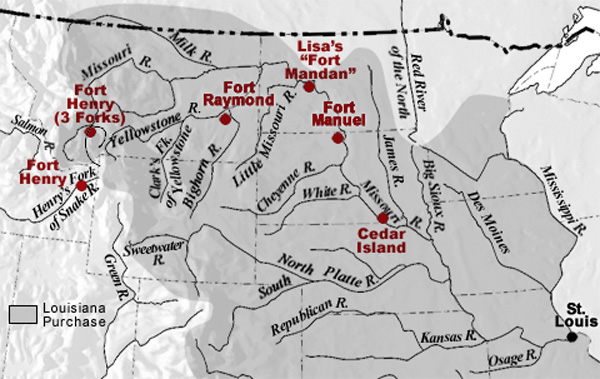

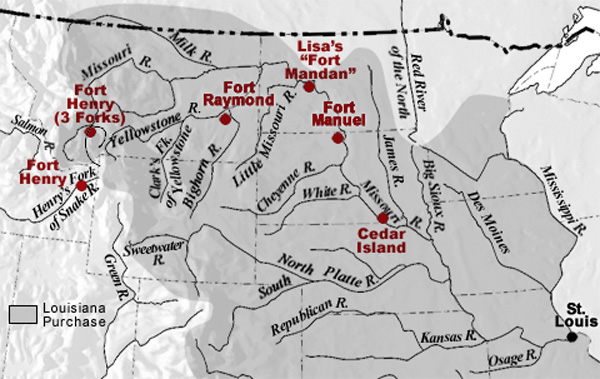

Manuel Lisa’s men at Fort Raymond not only encouraged the Crows to come trade with them, but they set out parties to trap beaver on their own. It was the latter effort that led to hostilities with the Blackfeet that affected Potts, Drouillard, and Colter.

Larocque at Fort Mandan

by Joseph A. Mussulman

In the fall of 1804, Larocque’s job was to take a supply of North West Company merchandise to the Mandan and Hidatsa villages and trade for furs. While there, he asked the captains if he could join the expedition.

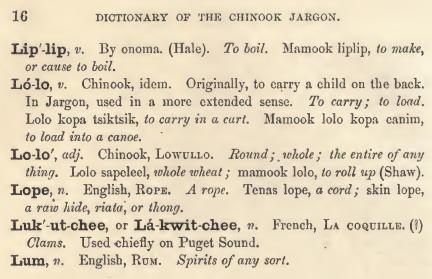

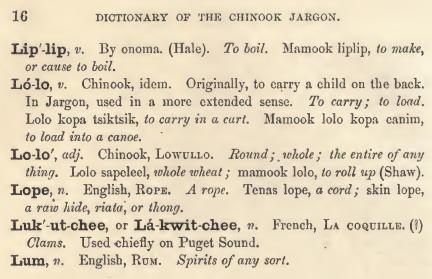

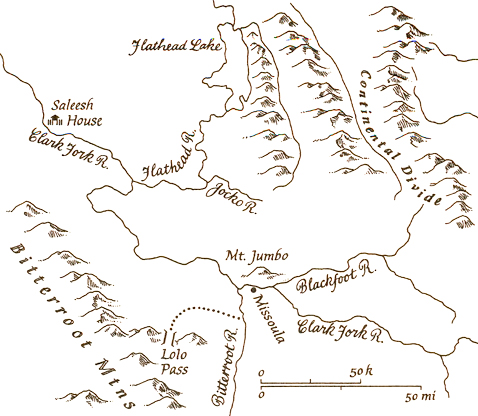

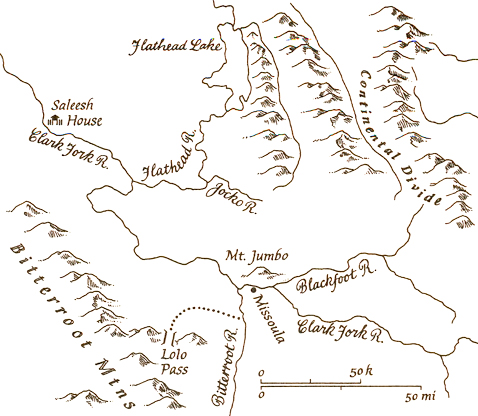

The verb, lolo, in the Chinook Trade Jargon, meant “to carry, load, bear, bring, fetch, transfer, lug, or pack.” Thus a “lolo” was a “carrier.”

The 1804-1805 Lewis and Clark journals provide the first reliable biological documentations of beaver (Castor Canadensis) for the Missouri and Columbia River corridors between St. Louis and the Pacific Ocean.

This is where, in 1828, John Jacob Astor’s American Fur Company built Fort Union, which remained the axis of Indian-American commerce on the Upper Missouri until the late 1860s.

Trade Beads

Essential supplies

Lewis’s preliminary list of supplies and equipment needed for the expedition, drawn up in the spring of 1803, included blue beads. “This is a coarse cheap bead,” he wrote, “imported from China….”

The first written record of a man named Lolo appeared in the field notes of David Thompson while at today’s Kettle Falls on the Columbia River. Fifteen years later, trader John Ashley mentions a “Mr. Lolo.”

Fur Trade after the Expedition

by W. Raymond Wood

The Louisiana Purchase and the lure of its beaver population led to a veritable flood of traders and trappers moving toward the Upper Missouri and the Northern Rocky Mountains and the slow abandonment of the overland trade in the United States by Canadian and British interests.

On 30 July 1806 Clark and his party camped near the mouth of the War har sah, or Powder River. He summarized the Yellowstone’s attractions, directing most of his attention toward opportunities for immediate expansion of the fur trade.

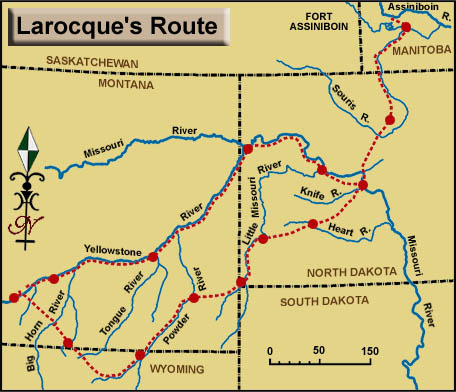

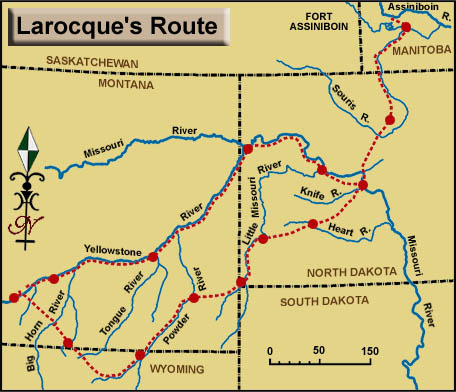

Larocque’s Yellowstone Journey

One year before Clark

The fourth literate explorer to go up the Yellowstone (and before Clark) was François-Antoine Larocque, who is important to the story of Lewis and Clark on the Middle Missouri for several reasons.

One of the tasks assigned to the expedition was to replace the French, Spanish, and English peace medals previously gifted to North American Indians with those from the United States. The gifts symbolized mutual loyalty in trade and, at least to the Indians, military protection.

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.