The following are extracts from We Proceeded On, the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation.[1]James J. Holmberg, “William Clark, York, and Slavery,” We Proceeded On, August 2021, Volume 47, No. 3. The full reprint is provided at … Continue reading

Clark and Slavery

Slavery was a fact of life in America until December 1865. Its boundaries expanded and then shrank over time, but it didn’t officially end in the United States until the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution went into effect. It is a blot on America’s conscience and was a major reason for the bloody and tragic four-year Civil War. But for tens of thousands of White Americans it was part of their way of life and sometimes represented a significant portion of the value of their assets. Even if some owners questioned the morality of the “peculiar institution,” they accepted it and propagated it. Thomas Jefferson likened slavery to having a “wolf by the ear;” you wanted to let go but you couldn’t. His admonition that slavery and the controversy it and its expansion caused were a “fire bell in the night” ringing a warning of future trouble was prescient.[2]Thomas Jefferson to John Holmes, 22 April 1820, Thomas Jefferson Papers, Library of Congress online collection: https://www.loc.gov/resource/ mtj1.051_1238_1239/?sp=1. Not everyone wanted to let go, of course, or listen to that bell. Many a slaveholder believed that slavery was validated by the Bible and that Blacks were lower on the human scale of intellectual and societal development than Whites and therefore rightfully enslaved. Racism, custom, finances, and other factors combined to perpetuate slavery in areas of the United States until civil war and the Thirteenth Amendment ended it.

Harvey W. Scott and York Statues

This tyrptic was created by the editor from three separate photographs. The left image © 2020 by Ted Timmons; center and right image © 2021 by WikiMedia user Another Believer. Permission to use—for each photo and the whole tryptic—granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

On 20 October 2020 at Mt. Tabor Park in Portland, Oregon, vandals toppled—and seriously damaged—a statue of Harvey W. Scott—perhaps because of racist language published during his 40-year tenure as the editor of The Oregonian. A bust of York, was anonymously erected 20 February 2021—and anonymously removed 28 July 2021.

Materials used to construct York’s bust were all perishable. The plaque, made of paper on plywood painted to look like marble read:

York

The first African American to cross North America and reach the Pacific Coast.

Born into slavery in the 1770s to the family of William Clark, York became a member of the 1804 Lewis and Clark Expedition. Though York was an enslaved laborer, he performed all the duties of a full member of the expedition. He was a skilled hunter, negotiated trade with Native American communities and tended to the sick. Upon his return east with the Corps of Discovery, York asked for his freedom. Clark refused his request.

The date and circumstances of his death are unclear.[3]“Bust of York,” Wikipedia, accessed 19 January 2024, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bust_of_York

The relationship between Clark and York will likely remain a relevant topic for more than one generation.—KKT, editor

William Clark was born in Caroline County, Virginia, in 1770. He moved to Kentucky with his family when he was fourteen. In 1808, he moved to St. Louis and lived there until his death in 1838. All three states in which he lived were slave states. Slavery was an acceptable institution in his world. The Clarks were a slaveholding family. William grew up among family slaves. In 1799, he inherited slaves in his father John Clark’s will. He is known to have purchased at least one slave and most likely more, planned to sell slaves from time to time, freed at least two, and owned slaves to his dying day. In his classic book, Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America, Ira Berlin makes a distinction between a slave society and a society with slaves. Virginia was a slave society. Kentucky in its early years was also, before gradually transitioning to a society with slaves.

This also was true for Missouri, where William lived for the last thirty years of his life. William Clark’s society and family shaped his beliefs and opinions about African Americans in general, enslaved African Americans specifically, and, inevitably, the institution of slavery. In 1770, the year of Clark’s birth, slaves comprised forty-two percent of Virginia’s population. In 1800, when he was settled on his farm outside Louisville and the legal owner of some twenty slaves, African Americans in bondage comprised just over eighteen percent of Kentucky’s population. The majority of slaves lived in the Bluegrass region of the state, including Jefferson County where Clark’s Mulberry Hill farm was located. As Americans moved farther west and into Missouri, many of them were slaveholders and brought their human property with them. In 1820, the year before Missouri became a state and the last year of Clark’s tenure as territorial governor, slaves comprised fifteen percent of Missouri’s population.[4]Ira Berlin, Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1998), 369; Lowell H. Harrison, The Anti-Slavery Movement … Continue reading Slavery was an institution everywhere William lived, and as a slaveowner he was a participating member. It was part of who he was.

Addressing Presentism

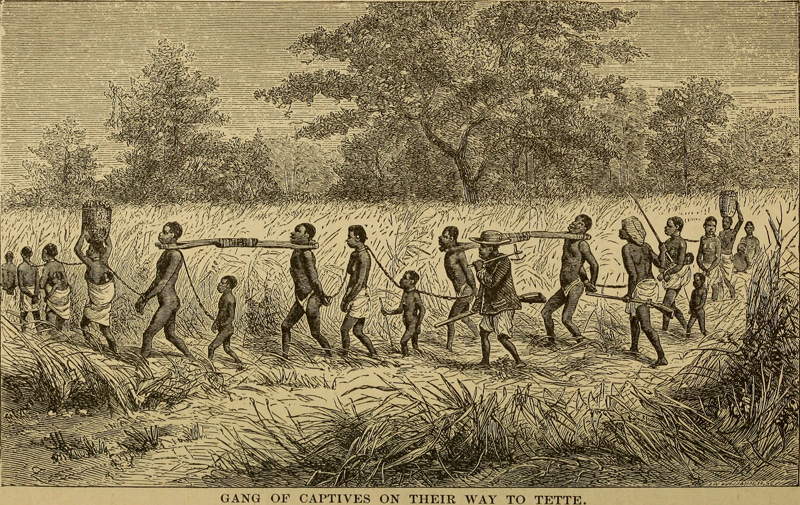

Gang of Captives on Their Way to Tette

From Stanley and the White Heroes in Africa . . ., D. M. Kelsey, ed. (1890), archive.org/details/stanleywhitehero00kels/.

Does owning slaves make William Clark a bad person? By today’s standards, yes. But as historians and others remind us, you cannot judge people and their society and actions from the past by what is considered proper or morally defensible now. What is called presentism can be fraught with unfair and erroneous judgments of historical people and their actions. Were some of Clark’s actions toward his enslaved African Americans harsh? Yes. Were they unfeeling? Yes. But by the standards of a slaveholding society of the early nineteenth century they were common and expected. William Clark was a firm believer in not only his responsibilities as a master but also in what his slaves’ responsibilities were. If they obeyed him and performed their “duty” as slaves, then he would try to do right by them as best he could. That didn’t necessarily mean they would agree with or like his decisions but, as he was their master and owner, it was their duty to obey him. White slave masters made the rules. Slavery was an abhorrent institution and the human suffering and tragedy caused by it are beyond counting. Owners, depending on their needs, could act callously toward their human property because they believed they had no choice or simply because they could. Clark acted as he believed his circumstances dictated, even when he feared people would misunderstand and be critical of his actions.

William Clark’s beliefs regarding African Americans, especially enslaved ones, are documented in his own words in letters to his brother Jonathan. His opinions and beliefs were formed from childhood by the society in which he lived and interactions with the enslaved on a regular basis. By the time he was an adult William’s views were well entrenched. Flashes of enlightenment regarding the peculiar institution and its victims were fleeting and, like Jefferson, he probably felt as trapped in it as the enslaved. In December 1802 while preparing to move across the Ohio River from slaveholding Kentucky to free Indiana Territory, Clark freed one slave. On 10 December 1802, stating that “in consideration of services rendered me and regarding perpetual involuntary servitude to be contrary to principles of natural justice,” Clark freed Ben Gee (or McGee). While his statement might seem to indicate that he’d had an epiphany about the wrongness and inhumanity of slavery, in reality, it was a boilerplate statement and a legal dodge. There is no record of his freeing any of his other slaves at this time even though he brought more members of his household than only Ben across the river to Indiana. The next day the legal maneuver was revealed. On 11 December, Clark and Ben returned to the Jefferson County courthouse and Ben bound himself to Clark for thirty years. The condition of slave had been exchanged for that of an indentured servant. Not only could the treatment of indentured servants be worse because the master no longer had a financial investment in them, but thirty years might have been intended to span the rest of Ben’s life. As it turned out, Ben likely was released from his indenture after almost eighteen years in 1820.[5]Jefferson County (KY) Bond and Power of Attorney Book, 2:201–2. There is a question whether Clark actually owned Ben at the time he freed him. Ben had been willed to John Clark’s grandsons … Continue reading

In July 1803 when Meriwether Lewis‘ invitation to join him on the expedition arrived, at least some of William’s slaves were living at the Clark farm at the Point of Rocks on the eastern edge of Clarksville and in free territory. Some of them apparently continued to live there with brother George Rogers Clark while William was away on the expedition. Others might have lived with other Clark family members, with Jonathan at his Trough Spring plantation southeast of Louisville, or perhaps they were hired out in their master’s absence. When William moved to St. Louis, he took certain slaves with him and left others at the Clarksville farm. In December 1810 William remarked to Jonathan in a letter that he wanted to make sure the “Old Negrows” at the farm at the Point did not suffer and were taken care of.[6]William Clark to Jonathan Clark, 14 December 1810, in James J. Holmberg, ed., Dear Brother: Letters of William Clark to Jonathan Clark (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002), 251–252n. The entire … Continue reading The assumption is that these elderly African Americans still were slaves belonging to William. While records are spotty, there is no evidence that William freed anyone other than Ben Gee whom he took to St. Louis.

Clark and York

The Clark home known as “Mulberry Hill,” built under the supervision of Jonathan and George, William’s older brothers in 1783-84, by slaves who included Old York, the father of William Clark’s personal slave, who was also called . The rest of the Clark family, including 14-year-old William, arrived here in March 1785. In 1799 William inherited the house from his father, and in 1803 sold it to Jonathan. It remained in the Clark family until its collapse in the early 1900s. This photo was taken about 1890.—Joseph Musselman, ed.

William Clark’s relationship with York is especially troubling and serves as a tragic example of how the institution of slavery whereby one person owns and rules the fate of another could affect the enslaver as well as the enslaved. It was Jefferson who said, “the [White] man must be a prodigy who can retain his manners and morals undepraved by such circumstances.” I stated previously that I believe William Clark was a good person. That he was an honorable man. But he was formed by his times and society. He was the product of a slave-holding society and a slave-owning family. He was a military man. He felt a great sense of duty and responsibility to family, friend, and country. And, in the context of the times and society, he felt a duty and responsibility to his enslaved African Americans. He believed he must do right by them—if they did right by him.

The master-slave relationship was one of reciprocal responsibilities. For one, it was their duty to obey their owner. To fulfill their duties and contribute to their owner’s success. Disobedience, recalcitrance, disrespect, violence, and other forms of misbehavior were unacceptable. Their punishment could take various forms, with whipping being a common one, and as William’s letters document, such punishment was meted out to both male and female slaves. Such corporeal punishment also was administered to indentured servants, soldiers and sailors, children, and others. For William to punish his “people” was considered very acceptable—as long as they deserved it—especially if you had a reputation for being a “good” master. Hiring your slaves out as a means of making money was standard. And, as circumstances dictated, selling your human property was common practice. What you didn’t do—if you were a responsible master who took care of his slaves—was separate families if it could be avoided, sell your slaves without reasonable cause, or abuse them unjustly. If those enslaved failed to uphold their responsibilities and gave their owner reason to set aside that master-slave understanding, then various forms of punishment, incarceration, hiring out to a severe master, and selling were all options. And that was the post-expedition path that William and York’s relationship took.

The mistake should never be made that the two men were friends. They were master and slave, owner and property, superior and inferior. As close as that relationship was for the many years and countless miles they were by each other’s side, for all the dangers and hardships they shared their relationship always was based on William as master and York as servant. All indications are that the relationship was stable and could maybe even be described as good from boyhood through the expedition.

There only are two known mentions of York prior to the expedition, and one is only a possibility. While serving in the army, William corresponded with his sister Fanny O’Fallon. In his 1 June 1795, letter from Greenville, Ohio, he expressed his pleasure in receiving letters from her and friends “by my Boy who arrived here a fiew days ago.” Although not definite, the likeliest person to be that “boy” was York who had been assigned to William from childhood and was experienced in the ways of frontier travel. Slaves were commonly dispatched over long distances in the service of their owners if capable and trusted. Taking York on an expedition across the American West clearly illustrated that he had confidence in York’s abilities to contribute not only to camp duties but to the successful advancement of the journey. The other mention is York’s inclusion in John Clark’s will of 1799 whereby he and a number of other slaves were inherited by William. Even though York acted as William’s servant and at his direction, legal ownership until then had remained with John Clark. This was true for other Clark slaves who were serving and even living with William’s siblings.[7]William Clark to Fanny Clark O’Fallon, 1 June 1795, Holmberg, ed., Dear Brother, 273; Jefferson County (KY) Will Book, 1:86–90. Referring to adult African American men as “boy” … Continue reading

York’s Contributions

“Explorers at the Portage” (detail)

Great Falls Tourist Center

© 2015 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

York almost certainly accompanied Clark in his travels before, during, and after his army service. Clark traveled extensively in the 1790s and early 1800s before joining the expedition. York is not mentioned in Clark’s non-expedition journals, which speaks to the invisibility of slaves. If they did their duty they were rarely if ever mentioned. If they misbehaved or the owner had other reason to complain about them (such as in William’s letters to Jonathan about Easter, Venos, and some of his other slaves) or they did something of particular note perhaps, they were more likely to be mentioned. William knew that York could perform all the necessary duties to make camp life easier for him and Meriwether Lewis, as well as the duties needed to advance the Corps. Having grown up on the frontier, York could hunt, track, and handle weapons, horses, and boats. He could swim, something that some of the expedition’s personnel couldn’t do. And perhaps, given their many years together, William simply was comfortable having York by his side. He was someone whom he could rely on and trust, almost something of a shadow.

An added bonus, something unanticipated when William decided to have York accompany the expedition, was the sensation York caused among some of the Native American Nations. York is mentioned in the expedition journals of Clark and others more frequently than most of the other members. This is partly due to comments about the Indians’ reaction to him. Those Indians who had never seen a person with black skin before believed him to have great spiritual power. The Arikara, Mandan, and Hidatsa were particularly impressed, and he was called Big Medison.

The journals and various sources relate York’s special status with Native Americans and also York’s reaction to it. For the first time in his life, the color of his skin made him special, and in the eyes of some of the Native people superior to those with white skin. Having been told he was inferior his whole life despite being near the top of the slave pecking order as the servant of a Kentucky gentleman and soon to be national celebrity, he was believed by some Natives to be superior to his owner. At least on one occasion, according to Clark, York got a bit carried away with his tale of once being wild and captured and tamed by Clark but still liked to eat little children. One can understand his reaction. Amazement, shock, and perhaps a growing understanding that he was not inferior to Whites because of his black skin.

It is through the expedition journals, Clark’s post-expedition interviews with Nicholas Biddle, and Pierre-Antoine Tabeau‘s recollection of seeing York when the Corps visited the Arikara that we gain our best understanding of York’s experiences and his physical appearance. Tall, well-built and perhaps heavy (Clark refers to him as “fat” in one 1804 entry), agile, very strong, hair cropped short, a good dancer, and as “black as a bear.”[8]York appears periodically in the Lewis and Clark Expedition journals regarding various topics—such as health, hunting, horse play, taking care of the dying Charles Floyd, and especially interaction … Continue reading

Post Expedition Expectations

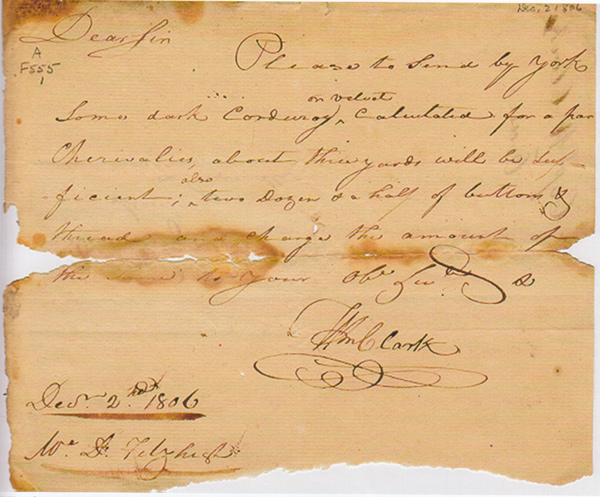

Transcription:

Dear Sir,

Please do Send by York Some dark Corduroy on velvet Calculated for a Jan[?] Cherivalies about three yards will be sufficient; also two Dozen & a half of buttons & thread and change the amount of the [same?] to

your [obedient servant?]

WM. CLARK

Dec 2nd 1806

Did York believe life would return to its pre-expedition routine once he and Clark were home? Life in Louisville or Clarksville with periodic trips? Despite being separated from his wife and possible children and other family members, York knew he’d be returning home. He and his master were in the same boat, so to speak—they both were separated from family. But that soon changed. In January 1808, William wed Julia Hancock in Fincastle, Virginia. Was York with him? Most likely. After a visit in Louisville, it was off to St. Louis, where they would live. William was taking his wife. York wasn’t. York’s wife was owned by someone else. Whether William attempted to acquire her so that she could accompany her husband to St. Louis is not known. And if there were children, what about them? It is likely that William declined to try to acquire York’s wife. He already had more slaves than he needed. He hired most of them out upon arriving in St. Louis. The situation the two men had experienced during years of travel and separation from family now was different. William had his wife with him in a new town, far from their Falls of the Ohio home. York did not. Upon return from the expedition, unlike every other member of the Corps, York didn’t receive any pay or a land grant. And he didn’t receive his freedom. He was Clark’s property and not an official member of the party. Any compensation or reward was up to his master. York did get store bought clothes and boots, but he didn’t get his freedom.

It’s a popular belief that Clark promised York his freedom if he went on the expedition and did good service on it. This is not documented by any known source. Clark was an honorable man. If he had promised York manumission, he undoubtedly would have followed through. His comments on York and their eroding relationship after the move to St. Louis attest to this. Instead, it was a case of York’s being where his master wanted him to be. Whether a three-year trip to the Pacific Ocean or a permanent move to St. Louis, it was York’s duty to obey William and do his duty as a good slave should. If that meant he must “give over that wife of his,” as Clark insensitively put it, then that’s what he must do.[9]Betts and Holmberg, In Search of York, 153–5, 192n. Clark’s brother-in-law Dennis Fitzhugh (sister Fanny’s third husband) was a partner in the mercantile firm of Fitzhugh and Rose. A … Continue reading

But York didn’t want to give up his wife and family in Louisville. Perhaps for the first time in their essentially lifelong relationship, York balked at his master’s orders. William records it in his own words in letters to his brother Jonathan. Upon arrival in St. Louis, William put York to work tending the garden and horses and doing other chores. In late August their relationship was still stable enough that William trusted York to go to St. Charles in search of a runaway slave.[10]William Clark to Jonathan Clark, 21 July 1808, and ca. 1 March 1809, Holmberg, ed., Dear Brother, 144, 197, 199n; Jackson, ed., Letters, 2:462463n. The runaway might have been York’s … Continue reading But trouble was brewing. York was unhappy in St. Louis, and he let his master know it. He wanted to return to Louisville to be with his family. The situation was increasingly aggravated by York’s refusal to resign himself to a new life in St. Louis. It is possible that something more than a desire to have York with him to perform certain work was involved. York had been his companion since their youth. William could rely on him. His presence may well have been a comfort to William, and now York wanted to leave him. Even if it were his wife, York was choosing someone else over him. Hurt feelings combined with a slave’s breaking the expected code of conduct preyed greatly on William’s mind. He recorded his dismay in his letters to Jonathan. His attitude and actions concerning York don’t reflect well on him. Today he is perceived as callous and cruel. Two centuries ago, even William feared his family might think him too severe regarding the treatment of his slaves, but he was within his rights as a slave owner.

Troubles with York

The statue of York on the campus of Lewis and Clark College, Portland, Oregon was scultped by Alison Saar. On the back of the enslaved man, she incised one of Clark’s maps showing “Yorks dry River” near the confluence of present Yellowstone and Powder rivers.

On 9 November 1808, William reported trouble with York. The two men were at odds and both had stubbornly dug in their heels regarding what they wanted. “I Shall Send York . . . and promit him to Spend a fiew weeks with his wife. he wishes to Stay there altogether and hire himself which I have refused. he prefers being Sold to return[ing] here, he is Serviceable to me at this place, and I am determined not to Sell him to gratify him.” Gratifying York as recognition and thanks for his years of faithful service, so he could be near his wife, seems perfectly reasonable, but that wasn’t necessarily the way of slavery in 1808 America. A slave who made such demands was defying his master and order and discipline must be maintained.

This had become a contest of wills. Taking the risk of being hired out was uncertain enough, but to ask to be sold so he could be in Louisville near his wife was fraught with danger and possible heartbreak. Unless York somehow got the right of refusal regarding to whom he was sold, he could find himself with an owner who wouldn’t permit him to visit his wife, or he might find himself taken away from Louisville if his new master moved or resold or hired him out to someone else. William’s anger and frustration were at such a level that he then threatened to do what seems the unthinkable. “If any attempt is made by york to run off, or refuse to provorm his duty as a Slave, I wish him Sent to New Orleans and Sold, or hired out to Some Severe master until he thinks better of Such Conduct.”[11]William Clark to Jonathan Clark, 9 November 1808, Holmberg, ed., Dear Brother, 160.

York becomes a recurring subject in William’s letters to Jonathan. For historians and readers today the information he imparts regarding York’s sad post-expedition fate and his own actions as a slaveholder is priceless, but very troubling. If the widening chasm in their relationship hadn’t bothered William, he wouldn’t have returned in his correspondence to his difficulties with York time and again. He hoped Jonathan would have sage advice on the topic of York and his other slave troubles. What that advice might have been is unknown because Jonathan’s letters most likely haven’t survived. A couple of weeks later, with York on his way to Louisville, William returned to the topic of his recalcitrant slave, writing Jonathan that he didn’t want York sold “if he behaves himself well. he does not like to Stay here on account of his wife being there. he is Serviceable to me here and perhaps he will See his Situation there more unfavourable than he expected & will after a while prefur returning to this place.”[12]William Clark to Jonathan Clark, 22, 24 November 1808, Holmberg, ed., Dear Brother, 172–3.

The deteriorating relationship continued to prey on William’s mind. On 10 December 1808, he again vented his frustration. His beliefs regarding York’s loyalty, service, and value reveal how wide that chasm of understanding and sympathy between owner and slave could be, and how pernicious slavery’s effects could be for both master and slave. For Clark, worried about personal and professional responsibilities and seeking ways to become financially secure, freeing a valuable piece of property—York—wasn’t possible. In a bit of slave owner rationalization William reasoned that York didn’t deserve his freedom, at least not yet, and blamed the situation on York’s refusal to give up his wife in Kentucky.

I wrote you in both of my last letters about York, I did wish to do well by him _ but as he has got Such a notion about freedom and his emence Services, that I do not expect he will be of much Service to me again; I do not think with him, that his Services has been So great (or my Situation would promit me to liberate him[)] I must request you to do for me as Circumstances may to you, appir best, or necessary and will ratify what you may do he Could [be freed] if he would be of Service to me and Save me money, but I do not expect much from him as long as he has a wife in Kenty. I find it is necessary to look out a little and must get in Some way of makeing a little, you will not disapprove of my inclinatuns on this Score, I have long discovered your wish (even beforee I went [on] the western trip) to induc me to beleve that there might be a raney day, Clouds Seem to fly thicker than they use to do and I think there will be a raney day.[13]William Clark to Jonathan Clark, 10 December 1808, Holmberg, ed., Dear Brother, 183–4, 185n.

Clark’s “raney day” notion regarding York continued. York took advantage of the opportunity to visit his wife and family and apparently told people he had permission to stay for four or five months rather than weeks. When word reached William of York’s exaggeration of the time allotted to him, Clark was more than a “little displeased.” “I do not wish the horses nor do I cear for Yorks being in this Country. I have got a little displeased with him and intended to have punished him but Govr. Lewis has insisted on my only hireing him out in Kentucky which perhaps will be best,” he wrote Jonathan on 17 December 1808. “This I leave entirely to you, perhaps if he has a Severe master a while he may do Some Service, I do not wish him again in this Country untill he applies himself to Come and give over that wife of his—I wishd him to Stay with his family four or five weeks only, and not 4 or 5 months —[.]”[14]William Clark to Jonathan Clark, 17 December 1808, Holmberg, ed., Dear Brother, 187.

It is interesting that Meriwether Lewis intervened on York’s behalf and persuaded his partner in discovery to take a less drastic course of action. Still, being hired out to a severe master would be a wretched experience, but in this war of wills between the two men, Clark was determined to win. A chastened, remorseful, and obedient York, resigned to giving up his wife and family in Kentucky, and requesting to return to his master, was Clark’s preferred resolution of the problem. Months passed with no word about York’s status. William’s curiosity and perhaps anticipation regarding York’s bending to his will was such by March 1809 that he asked Jonathan “what has becom of York? and the horse.”[15]William Clark to Jonathan Clark, ca. 1 March 1809, Holmberg, ed., Dear Brother, 197. Two possessions William had on his mind.

Whether York applied to William to return to St. Louis or the latter requested he be sent back isn’t known. During his stay in Louisville York might have been something of a floater among Clark family members or hired out only for short periods rather than the usual one-year term. But whatever his situation, he did not endear himself to the Clarks and other Whites. York apparently let his unhappiness and resentment be known. His behavior wasn’t what it should have been for a slave and that earned him the displeasure of the Clarks and others. William had exposed York’s dissembling about how long he had permission to stay in Louisville. York was violating the slave code of conduct. In short, he was a malcontent and possible troublemaker, setting a bad example for his fellow slaves. This is known because Edmund Clark wrote his brother in early September 1809, when he learned that William planned to send York back to Louisville after his return to St. Louis that spring, that “I don’t like him nor does any other person in this country and was it not for their friendship for you I Believe he w[oul]d have been roughfly used when he was up last.”[16]Edmund Clark to William Clark, 3 September 1809, William Clark Papers-Clark Family Papers Collection, Missouri Historical Society. This letter also is cited in Betts and Holmberg, In Search of York, … Continue reading

It was indeed back to Louisville for York after a brief return to St. Louis. William documents his “insolent and Sulky” behavior in letters to Jonathan. He became so disgusted with him that he sent him to Louisville to be hired out or sold. York might be near his wife and family but it was not for an enjoyable visit. He had fallen from one of the highest positions a slave could have, as the body servant to a high-ranking government official and national hero, to facing possible sale down the river to the Deep South or being hired out to a severe master. Manumission was still off the table as far as William was concerned. If he had hopes that York would have adjusted his attitude upon his return to St. Louis, he was disappointed. York was back with Clark by May 1809, and his letters to Jonathan continued to document York’s behavior. “He is here but of verry little Service to me, insolent and Sulky, I gave him a Severe trouncing the other Day and he as much mended Sence Could he be hired for any thing at or near Louis ville, I think if he was hired there a while to a Severe master he would See the difference and do better.”[17]William Clark to Jonathan Clark, 28 May 1809, Holmberg, ed., Dear Brother, 201. Clark uses the term “mended” meaning mended his ways rather than physically mended. It also is possible … Continue reading

And so it went that spring and summer between Clark and York. The latter’s behavior would improve after punishment but soon enough his resentment and disobedience would again manifest themselves and he’d be punished. In July York landed in jail. It isn’t known whether it was for violation of a law or at William’s direction. There is a story in St. Louis lore that York would frequent the taverns and tell tales of the expedition in exchange for drinks, get drunk, and be jailed. Or did Clark have him imprisoned as punishment for some wrongdoing? Whatever the reason, William reported in late July that “I have taken York out of the Caleboos and he has for two or three weeks been the finest negrow I ever had.” He then reported that he’d lost his favorite horse a few days earlier.[18]William Clark to Jonathan Clark, 22 July 1809, Holmberg, ed., Dear Brother, 204, 205n; Betts and Holmberg, In Search of York, 73–6.

York’s Fate

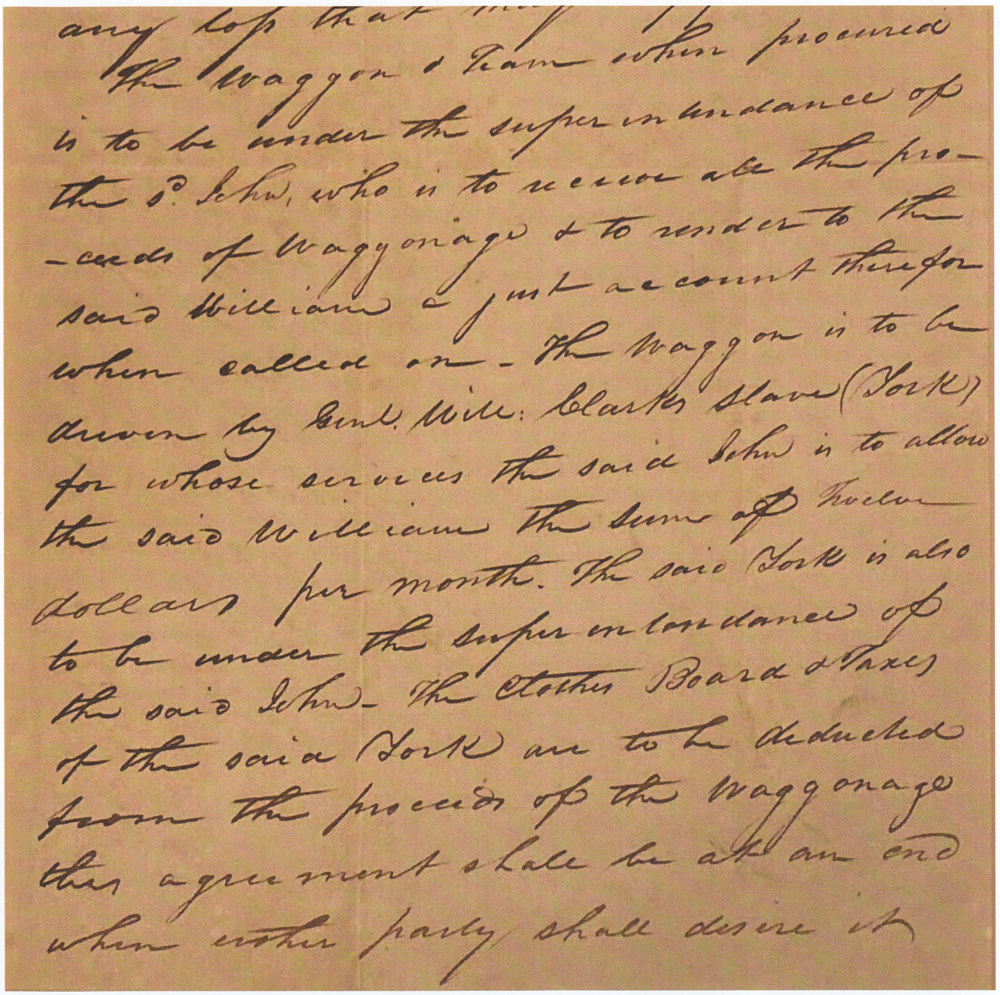

The above drayage business agreement between William Clark and John Hite Clark names York as the driver. Transcription:

The wagon & team when procured is to be under the superintendance of the P. John, who is to receive all the proceeds of Waggonage & to render to the said William a just account therefor when called on. The waggon is to be driven by Gent. Will. Clarks slave (York) for whose services the said John is to allow the said William the sum of Twelve dollars per month. The said York is also to be under the superintentdance of the said Joh, The Clothes Board & Taxes of the said York are to be deducted from the proceeds of the waggonage this agreement shall be at an end when either party shall desire it

By late August William was again so disgusted with York that he decided to wash his hands of him. “Since I confined york he has been a gadd fellow to work; I have become William Clark and John Hite displeased with him and Shall hire or Sell him,” he wrote Jonathan on 26 August. He was sending him to Wheeling as a boat hand in early September. When he arrived at Louisville on the return trip, “I wish much to hire him or Sell him I cant Sell negrows here for money.”[19]William Clark to Jonathan Clark, 26 August 1809, Holmberg, ed., Dear Brother, 210, 212n. This is the last letter to Jonathan in which William mentions York; and their correspondence continued for two … Continue reading York had so violated the master-slave code, William believed, that he deserved to be sold—to be turned into money. Whether there were no takers in Louisville and vicinity or a decision was made not to send him off with a slave trader to New Orleans or Natchez, William retained ownership of York. Instead, he was hired out, sometimes to neglectful or severe masters. It made William some money, but it didn’t necessarily teach York the error of his ways.

Life in Louisville was hard for York. He worked for the Clark family and also was hired out to severe masters who mistreated him. He worked as a wagon driver, which would play a role in his future. William’s nephew John O’Fallon had known York his whole life. York had been entrusted by William with accompanying O’Fallon on a trip from Louisville upriver to Maysville, Kentucky, or farther a few years after the expedition. In his instructions to his nephew, William stated that York knew how to handle both horses and a boat. In May 1811, O’Fallon wrote his uncle with the main purpose of informing him about York. It was reported that his wife’s owner was moving to Natchez and taking her with him, O’Fallon wrote. Inquiries indicated that York’s behavior had been good and with his wife’s leaving Louisville, would his uncle wish York to return to St. Louis? He confessed that he didn’t know the details of their “breach,” but York “appeared wretched under the fear that he has incurred your displeasure and which he despairs he’ll ever remove. I am confident he sorely repent[s].”[20]William Clark to John O’Fallon, memorandum, no date [ca. 1807–1808], John O’Fallon Papers, Filson Historical Society; John O’Fallon to William Clark, 15 May 1811, William Clark … Continue reading

His nephew’s plea on behalf of York didn’t persuade William to allow him to return to St. Louis. York remained hired out in Louisville. How severe his treatment was isn’t known, but O’Fallon’s comment in his 1811 letter that York had been “indifferently clothed if at all” indicates he wasn’t treated particularly well. By December 1814 William was ignorant of York’s situation, querying brother Edmund in a letter, “what have you done with . . . my negrow man York?”

In November 1815, William and his nephew John Hite Clark formed a drayage business in Louisville. The driver of the wagon, as stated in the business agreement, was “Genl. Will: Clarks Slave (York).” Nine years after the return of the Corps of Discovery from its epic journey, York still was a slave.[21]John O’Fallon to William Clark, 15 May 1811; William Clark to Edmund Clark, 25 December 1814, Clark Family Papers, Filson Historical Society; William Clark and John Hite Clark business … Continue reading What became of York after this is uncertain. He disappears from known documentary sources. Clark doesn’t include him on his list of the status of expedition members he recorded in the 1820s. It isn’t until Washington Irving visited William in St. Louis in 1832 that York’s apparent fate was revealed. In the course of their conversation, William reflected on York, reporting that he had set him free (not stating when), set him up in a freight hauling business with a route between Nashville and Richmond (Kentucky most likely), that he was a poor businessman, lost the business, “damned” the day he ever got his freedom, and died in Tennessee of cholera while trying to return to Clark in St. Louis, the year unnoted.

Is this true? Should it be given more weight than the story of the happier ending of York’s returning to the West and being a respected chief and warrior among the Crow Indians? In the early 1830s, mountain man Zenas Leonard met a Black man living among the Crow who said he had been with Lewis and Clark. But Leonard didn’t give his name. This has caused some to conclude that it was York. But there were other African Americans in the West who might have had dealings with Lewis and Clark. The person also might have been spinning a yarn.[22]Jackson, ed., Letters, 2:638–9; John F. McDermott, ed., The Western Journals of Washington Irving (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1944), 82; John C. Ewers, ed., Adventures of Zenas Leonard, … Continue reading The great weight of evidence supports an unmarked pauper’s grave in Tennessee as being York’s fate.

Why should we believe William Clark, a displeased master who opined that York was an ungrateful slave who eventually regretted being freed? While Clark might have engaged in the usual slaveholder rationalization that freed slaves regretted their freedom, he had no reason to lie about York’s fate. What he reported to Irving regarding York’s being a wagon driver is supported by contemporary documentation.

As York neared fifty years of age, William needed to free him if he intended ever to do so. In 1815 York would have been in his forties. If he were the same age as William or a few years younger, he would have reached that cut-off age of fifty in 1820 or perhaps a few years later. William also had a wide range of contacts. Even though he’d evidently washed his hands of York, that didn’t mean he was unaware of how he fared after being freed. When he learned of Meriwether Lewis’ death in October 1809, he immediately reached out to several contacts in Nashville for information. York was based in Nashville and perhaps those same contacts kept William informed about him. What he tells Irving is quite specific. If he told Irving further details, he unfortunately didn’t note them.

If William gave a year for York’s death, would it have been 1822? There were other cholera deaths in the region that year, including William’s brother-in-law Dennis Fitzhugh. The manner in which William reflects on York suggests that some years had passed since he’d been freed and died. Is an estimate of York’s manumission about 1820 and dying about 1822 reasonable? As mentioned earlier, William apparently released Ben from his indenture in 1820. We may never know when York was freed. This author continues to search for more information on York but further details relating to his freedom and death have not been found to date.

Conclusion

What are we to conclude about William Clark as a slaveholder? Should he be viewed through the lens of presentism? If so, his reputation would be that of the Simon Legree character from Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a cruel master with whip in hand. But is that fair to Clark and fair to history? Probably not. William Clark was the product of a slaveholding society and a slaveholding family. He was shaped by that culture. Recent Clark biographers Landon Jones, William Foley, and Jay Buckley concur. Did he believe African Americans were inferior to Euro-Americans? Yes. Did he believe slavery was wrong? On some level he probably did, yet, like Thomas Jefferson and many others, he believed it was a system in which both Whites and Blacks were trapped, Jefferson’s wolf by the ear. William Clark owned slaves until the day he died and willed them to his sons. The value of his human property was such that he believed he couldn’t afford freeing more than the occasional one. The Clarks had a reputation as “good” masters to their slaves. To be a bad or severe master was wrong and a blot on a slave-owning family’s good name. Owners didn’t abuse their slaves and slaves weren’t punished unless they deserved it.

William’s letters to Jonathan document the anxiety and frustration he experienced in trying to do right by York and his other slaves while at the same time requiring them to obey orders and uphold their responsibilities as slaves. When they failed to do so there were consequences in the form of escalating punishments from lost privileges and whippings to hiring out to a severe master or being sold.

While William might have been a stern task master and unsympathetic regarding the desires of his slaves, he wasn’t cruel to them, at least by the standards of the time. By those standards, he was not a severe master. He responded as he’d been conditioned to and as a slaveholding society expected him to-to maintain discipline and control over his slaves. This, of course, doesn’t entirely excuse his actions regarding York, Venos, Easter, Juba, Scipio, and his other slaves. But the culture and realities of William Clark’s world must be kept in proper perspective. Applying today’s societal mores and beliefs to those who inhabit history is a slippery slope and one that should be avoided. It isn’t necessarily fair or valid. This applies to William Clark as slaveholder. He could be a stern master, on occasion capable of meting out physical punishment to man and woman both. He could be demanding, callous, and perhaps unreasonable. But he was no exception to how even “good” masters treated their human property. By the standards of his day, he was a good and honorable man who loved his family and his country—and who tried to do right by the human beings he owned.

While York and other slaves of William Clark serve as examples of the pernicious institution of slavery, it should be kept in mind that its effects also impacted those who owned them, making them people of whom they might not have been proud and who today often are condemned for being or becoming who they were. The peculiar institution and its relationships between owner and owned are replete with contradictions and complexities. But that is part of human nature. William Clark was no exception. His actions as a slaveholder are contradictory. His relationships with his human property sometimes were complicated—as all relationships can be. His struggle to be a “good” master rather than a “severe” one was difficult at times. Clark had his flaws, just as all people do, and his actions as a slaveholder can be considered one of them; but he was a man of his times, culture, and upbringing, and they informed his beliefs and world view for better and worse. He may not have liked the institution of slavery, but he engaged in it and perpetuated it.

Further Reading

- York: Enslaved Afrikan Adventurer by Ahati N.N. Toure

- York’s Fallout over Freedom by Joseph Mussulman.

- York in the Journals

- African-American Song and York: Did He Sing? by Joseph Mussulman

- In Search of York: The Slave Who Went to the Pacific with Lewis and Clark, Robert B. Betts. Revised edition with a new epilogue by James J. Holmberg (Boulder, University Press of Colorado, 2000).

- Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America, Ira Berlin (Cambridge, Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1998).

- Generations of Captivity: A History of African-American Slaves, Ira Berlin (Cambridge, Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2003).

- Africans in America: America’s Journey through Slavery, Charles Johnson, Patricia Smith et al. (New York, Harcourt Brace & Company, 1998).

- American Slavery, Peter Kolchin (1619–1877. New York, Hill and Wang, 1993).

- A History of Blacks in Kentucky: From Slavery to Segregation, 1760–1891, Marion B. Lucas (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2003 second edition).

- White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide, Carol Anderson (New York: Bloomsbury Adult, 2017).

Notes

| ↑1 | James J. Holmberg, “William Clark, York, and Slavery,” We Proceeded On, August 2021, Volume 47, No. 3. The full reprint is provided at lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol47no3.pdf#page=23.—KKT, ed. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Thomas Jefferson to John Holmes, 22 April 1820, Thomas Jefferson Papers, Library of Congress online collection: https://www.loc.gov/resource/ mtj1.051_1238_1239/?sp=1. |

| ↑3 | “Bust of York,” Wikipedia, accessed 19 January 2024, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bust_of_York |

| ↑4 | Ira Berlin, Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1998), 369; Lowell H. Harrison, The Anti-Slavery Movement in Kentucky (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1978), 2; Slave, Free Black, and White Population, 1780–1830 (umbc.edu). |

| ↑5 | Jefferson County (KY) Bond and Power of Attorney Book, 2:201–2. There is a question whether Clark actually owned Ben at the time he freed him. Ben had been willed to John Clark’s grandsons John and Benjamin O’Fallon but was to be managed by their Uncle William and title transferred to him when the boys reached twenty-one years of age-still some ten years away. Clark apparently had acquired Ben or acted as if he had. Ben’s wife was Venus/Venos/Venice, who had been willed to George Rogers Clark. William had acquired her and two of her children from George in 1800 for services rendered on his behalf. William took Ben and Venus with him to St. Louis when he moved there in June 1808.The freeing and then indenturing of slaves was a legal ploy commonly practiced. An owner might free one or more slaves but still bring enslaved people across the river. In this early period the enforcement of the ban on slavery in what was the Northwest Territory was rather lax. Clark’s Mulberry Hill neighbor Robert K. Moore moved across the river to Clark County shortly before Clark and freed a couple of his slaves using the same language. It wasn’t until anti-slavery members of the territorial legislature gained a majority in 1809 that the slavery friendly treatment began to be ended. The 1816 state constitution specifically prohibited slavery. A letter in the Clark Family Papers at the Missouri Historical Society indicates that Ben was either released from his indenture or simply sent to live in Clarksville in 1820. The letter written in Ben’s name (probably by Clark’s nephew Samuel Gwathmey) from Clarksville, Indiana, on 3 June 1820, to Clark inquires about his trunk that Clark was going to send him. Ben already had received two boxes of his things (Clark Family Papers, Missouri Historical Society). |

| ↑6 | William Clark to Jonathan Clark, 14 December 1810, in James J. Holmberg, ed., Dear Brother: Letters of William Clark to Jonathan Clark (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002), 251–252n. The entire quote is “if the farm is broken up whuch I think well of I must draw your attention a little to the Old Negrows at the point, they must not Suffer when they have become infirm, may I beg of You to doo the best you Can with them So that they may not Suffer I will with much pleasure pay for expences which may be encured by them under your directions.” After brother George’s leg was amputated and he went to live at Locust Grove with his sister Lucy Croghan and her husband William the family had to decide what to do with the farm at Point of Rocks (present Clarks Point). It was sold but William retained land he owned in the immediate area along the river front. The old slaves living at the Point might have included Old York, Rose, Harry, Cupid, and others. The four named were over fifty years old in 1799. Whether all of them were living is not known, but Rose definitely was because she is mentioned in William’s 1816 runaway slave ad for her son Juba. In Kentucky slaves older than fifty weren’t to be freed because it was feared that they wouldn’t be able to earn a living and thus be a charity case. If they were moved to free territory that might have been legal, but they likely wouldn’t have been welcome there for the same reason. The original “Dear Brother” letters are in the collection of the Filson Historical Society. |

| ↑7 | William Clark to Fanny Clark O’Fallon, 1 June 1795, Holmberg, ed., Dear Brother, 273; Jefferson County (KY) Will Book, 1:86–90. Referring to adult African American men as “boy” was common practice as one of the methods of demeaning them and formalizing their inferior status. |

| ↑8 | York appears periodically in the Lewis and Clark Expedition journals regarding various topics—such as health, hunting, horse play, taking care of the dying Charles Floyd, and especially interaction with the Indians. See Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Lewis and Clark Expedition Day by Day (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2018) for a concise source regarding York on the journey; Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents 1783–1854 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 2:503, 539; Robert B. Betts, In Search of York: The Slave Who Went to the Pacific with Lewis and Clark, revised edition with a new epilogue by James J. Holmberg (Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2000), 57–60, 65–7, 179n. |

| ↑9 | Betts and Holmberg, In Search of York, 153–5, 192n. Clark’s brother-in-law Dennis Fitzhugh (sister Fanny’s third husband) was a partner in the mercantile firm of Fitzhugh and Rose. A collection of their ledgers and journals is in the Filson Historical Society’s Charles W. Thruston Collection. Entries from November–December 1806 and April and August–December 1807 record purchases for and errands by York, 5:83–4, 87, 91, 101, 256, 262, 328, 333–40, 351, 385, 390, 402–3, 411–3, 419–420, 444, 454–5; William Clark receipt, 2 December 1806, Dennis Fitzhugh Papers, Filson Historical Society; William Clark to Jonathan Clark, 2 July 1808, 9, 22, 24 November 1808, and 10, 17 December 1808, Holmberg, ed., Dear Brother, 139, 160, 172–3, 183–4, 187. |

| ↑10 | William Clark to Jonathan Clark, 21 July 1808, and ca. 1 March 1809, Holmberg, ed., Dear Brother, 144, 197, 199n; Jackson, ed., Letters, 2:462463n. The runaway might have been York’s half-brother Juba. Clark reported his difficulties to Jonathan regarding his running off and being offered for sale. |

| ↑11 | William Clark to Jonathan Clark, 9 November 1808, Holmberg, ed., Dear Brother, 160. |

| ↑12 | William Clark to Jonathan Clark, 22, 24 November 1808, Holmberg, ed., Dear Brother, 172–3. |

| ↑13 | William Clark to Jonathan Clark, 10 December 1808, Holmberg, ed., Dear Brother, 183–4, 185n. |

| ↑14 | William Clark to Jonathan Clark, 17 December 1808, Holmberg, ed., Dear Brother, 187. |

| ↑15 | William Clark to Jonathan Clark, ca. 1 March 1809, Holmberg, ed., Dear Brother, 197. |

| ↑16 | Edmund Clark to William Clark, 3 September 1809, William Clark Papers-Clark Family Papers Collection, Missouri Historical Society. This letter also is cited in Betts and Holmberg, In Search of York, 164. |

| ↑17 | William Clark to Jonathan Clark, 28 May 1809, Holmberg, ed., Dear Brother, 201. Clark uses the term “mended” meaning mended his ways rather than physically mended. It also is possible that he intended “minded” rather than “mended” but if so the “i” is not dotted and slightly open. |

| ↑18 | William Clark to Jonathan Clark, 22 July 1809, Holmberg, ed., Dear Brother, 204, 205n; Betts and Holmberg, In Search of York, 73–6. |

| ↑19 | William Clark to Jonathan Clark, 26 August 1809, Holmberg, ed., Dear Brother, 210, 212n. This is the last letter to Jonathan in which William mentions York; and their correspondence continued for two more years until Jonathan’s death in November 1811. |

| ↑20 | William Clark to John O’Fallon, memorandum, no date [ca. 1807–1808], John O’Fallon Papers, Filson Historical Society; John O’Fallon to William Clark, 15 May 1811, William Clark Papers-Clark Family Papers Collection, Missouri Historical Society. |

| ↑21 | John O’Fallon to William Clark, 15 May 1811; William Clark to Edmund Clark, 25 December 1814, Clark Family Papers, Filson Historical Society; William Clark and John Hite Clark business agreement, 14 November 1815, John H. Clark Papers, Filson Historical Society. |

| ↑22 | Jackson, ed., Letters, 2:638–9; John F. McDermott, ed., The Western Journals of Washington Irving (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1944), 82; John C. Ewers, ed., Adventures of Zenas Leonard, Fur Trader (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1959), 51–2, 139, 147–8; Betts and Holmberg, In Search of York, 135–43, 167–70; Holmberg, ed., Dear Brother, 98n–99n. Two events in 1820 also point to it as the possible year in which Clark freed York: the deaths of his wife Julia and her father George Hancock. Their deaths had estate implications, including the disposition of slaves that Julia had received from her father. With these events and the clock that was ticking toward York’s fiftieth birthday, perhaps Clark believed that the time had come to free him. One also wonders if the horses and wagon acquired for the 1815 drayage business with his nephew were the same ones given to York for his business upon being freed. |