The military molded the Corps of Discovery and its co-captains into an effective unit for exploring the continent. Prior to the Lewis and Clark Expedition, William Clark and Meriwether Lewis began their military careers by actively serving in their local militias. After that, they joined the regular army and first met during the Ohio Valley’s Indian wars.[1]Extracts from Sherman L. Fleek, “The Army of Lewis and Clark,” We Proceeded On, Vol. 30 No. 4, November 2004, 8–14. The original full-length article is available at our sister site, … Continue reading.

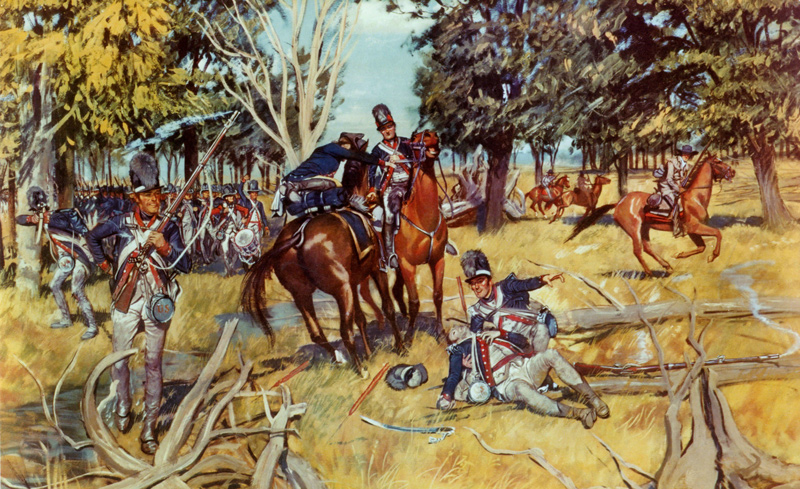

The text accompanying this poster:

Banks of the Maumee, Ohio, August 1794. Anthony Wayne commanded the Army, enlarged in 1792 and formed into the Legion (now 1st and 3d Infantry Regiments). He trained it into a tough combat team to beat the Indians of the Northwest who had twice whipped us. The Legion advanced into Indian country, feeling its way cautiously. On 20 August 1794 it tracked down the foe, routed him from behind a vast windfall, and destroyed his warriors. Thus the way cleared for the new nation to expand into the Ohio Valley.[2]Army Posters and Prints, history.army.mil/catalog/pubs/21/daposters/21-38.html accessed 30 Nov 2022.

Militias

The Lewis and Clark Expedition was first and foremost a military enterprise—outfitted by the War Department, manned by soldiers of the U.S. Army, and led by two commanders who had met a decade earlier while serving as junior officers on the frontier.

Before they were commissioned officers in the regular army, William Clark and Meriwether Lewis served as citizen soldiers in the militia, the predecessor of today’s National Guard. Clark joined the Virginia militia as a 19-year-old in 1789 and also served in the Northwest Territory and Kentucky militias. After transferring to the regular army in 1792 as a lieutenant of infantry, he fought in several significant engagements in the Ohio Valley’s Indian wars, including the Battle of Fallen Timbers, before resigning his commission and returning to civilian life. Lewis joined the Virginia militia as a 20-year-old in 1794, during the Whiskey Rebellion, and obtained a commission as an ensign in the regular army in 1795. He was later promoted to lieutenant and then captain, the rank he held while on detached duty as President Thomas Jefferson’s personal secretary during the first two years of his administration.

Militias offered many American males their first (and in most cases only) military experience. This had been so since the mustering of the first colonial militias in the 1630s. Militia units served bravely during the American Revolution but in general were outmatched by British troops. The better trained and disciplined Continental Army provided the core of the tiny postwar regular army, which in the years immediately following the Revolution shrunk to a force as small as eighty men, with a captain as the senior ranking officer.[3]Alan R. Millet and Peter Maslowski, For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States of America (New York: The Free Press, 1994), 91; Michael D. Doubler, I Am the Guard: A History of … Continue reading The national military’s small size reflected Congress’s strapped finances, its fear of a large standing army, and a continued reliance on militias for defense. The Militia Act of 1792 made all white males between the ages of 18 and 45 members of the enrolled, or common, militia. The first men recruited by Lewis and Clark for the expedition—the famed nine young men from Kentucky—were all, by definition, members of the enrolled militia. Whether any of them had ever participated in militia drills isn’t known, but it is perhaps telling that the balance of men recruited in the fall of 1803 were members of regular army units.[4]The nine young men from Kentucky were John Colter and George Shannon (recruited by Lewis in Pittsburgh) and William Bratton, Joseph Field, Reubin Field, Charles Floyd, George Gibson, Nathaniel Pryor, … Continue reading

Following the adoption of the Constitution, in 1788, Congress established the War Department within the executive branch and confirmed Henry Knox, who had served as George Washington’s chief of artillery during the Revolution, as the first secretary of war. Knox’s domain encompassed the army, navy, and marines as well as all federal arsenals and coastal defenses. The Navy Department was established in 1798, during the administration of John Adams, in response to maritime threats from both Great Britain and France.[5]Warren W. Hassler, Jr., With the Shield and Sword: American Military Affairs, Colonial Times to the Present (Ames: Iowa State University Press, 1982), 50 and 63. Adams’s fellow Federalist but political rival Alexander Hamilton, meanwhile, conceived an ambitious plan to greatly expand the army with the addition of twelve infantry regiments. Hamilton himself would mold and ultimately lead this New Army, as it was called, but his grandiose scheme came to naught when Congress, after much debate, refused to fund it.[6]Theodore J. Crackel, Mr. Jefferson’s Army: Political and Social Reform of the Military Establishment, 1801–1809 (New York: New York University Press, 1987), 32–33.

The Ohio Campaigns

The regular-army service of Clark and Lewis had begun a decade earlier under the command of Major General “Mad Anthony” Wayne, the crusty, competent Revolutionary War veteran who directed military operations against the Miamis, Shawnees, and other confederated tribes of the Northwest Territory. Wayne, the army’s highest-ranking officer, took charge in 1792 after a massacre on the Wabash River of more than six hundred soldiers commanded by his predecessor, Arthur St. Clair. (In their lopsided victory, the Indians lost perhaps forty men.)[7]Landon Y. Jones, William Clark and the Opening of the West (New York: Hill & Wang, 2004), 12. The debacle led to a major restructuring of forces. In a name evocative of the Roman Republic, the U.S. Army became the Legion of the United States. The legion was divided into four sub-legions, each commanded by a brigadier general and with a complement of 1,280 men. A sub-legion comprised eight companies of infantry, four companies of riflemen, and a company each of artillery and dragoons (cavalry). In theory, this structure did a better job of integrating forces, thereby increasing tactical flexibility.[8]Gregory J.W. Urwin, The United States Infantry: An Illustrated History, 1775–1918 (New York: Sterling Co., 1991), 33; Francis B. Heitman, Historical Register and Dictionary of the United States … Continue reading

A strict disciplinarian, Wayne spent more than two years training his troops before the army again took to the field against the Indian confederacy, in a campaign that culminated on 11 August 1794, in the decisive Battle of Fallen Timbers. The officers distinguishing themselves in that engagement included 24-year-old Lieutenant William Clark, who led a column of riflemen on Wayne’s left flank and drove the enemy back a mile.[9]Jones, 78. Hostilities ended soon after, but the army (and Clark) remained garrisoned in the Ohio country to ensure the peace. In November 1795, Clark was placed in command of the Chosen Rifle Company of the Fourth Sub-Legion.[10]The word “chosen” shouldn’t be thought of as synonymous with “elite,” a term associated in today’s military with crack, highly trained units like the Rangers and … Continue reading Soon afterward, a 21-year-old ensign named Meriwether Lewis was transferred to Clark’s unit following his court martial on charges of insulting a superior officer. Lewis was acquitted, but he and the offended officer were in the same company, and Wayne must have ordered Lewis’s transfer to prevent another altercation. In 1796, in yet another reorganization, the army abandoned the legion concept and returned to a regimental structure. Lewis then became a member of the First Regiment of Infantry. By this time, Clark had resigned his commission and returned to civilian life.

1802 Reduction in Force

In the view of Thomas Jefferson, Hamilton’s proposal for a large standing army represented a direct threat to freedom and republican values.[11]Jefferson’s fears of a standing army are well known, but militias concerned him, too. “Beware of a military force, even of citizens,” he wrote to a friend in early 1800. (Crackel, … Continue reading When Jefferson assumed the presidency, in 1801, Federalist supporters of a strong military feared the worst; as one officer wrote to a friend, “the navy will be hauled up—the army disbanded.”[12]Edward M. Coffman, The Old Army: A Portrait of the American Army in Peacetime, 1784–1898 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), 3. Jefferson lost no time giving the army what he called “a chaste reformation.”[13]Thomas Jefferson to Nathaniel Bacon, May 14, 1801. Albert Ellery Bergh, ed., The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, 20 volumes. (Washington D.C.: The Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association, 1907), 10:261. The entire regular army comprised barely four thousand officers and men. Most officers were Federalists, and many were veterans of the Revolution long past their prime. A principal reason Jefferson made Captain Meriwether Lewis his personal secretary was his knowledge of the officer corps, and one of his first assignments was compiling a list of expendable officers; more than half were trimmed from the roster.[14]Donald Jackson, “Jefferson, Meriwether Lewis, and the Reduction of the United States Army,” in James Ronda, ed., Voyages of Discovery: Essays on the Lewis and Clark Expedition (Helena: … Continue reading Jefferson ultimately reduced the army to about three thousand men in two regiments of infantry, one large regiment of artillery, and a small corps of engineers.[15]Millet and Maslowski, 105. Jefferson also downsized the navy. He stopped work on several ships of the line and a dozen or so frigates in favor of a “mosquito” navy of armed sloops. Logistical and administrative support for line units was provided by bureaus in Washington, D.C., whose officers reported directly to the secretary of war.

Notwithstanding his fear of a standing army, Jefferson was a realist who understood the importance of a viable military to a young nation threatened by imperial powers on its borders and hostile Indians along its frontiers. He also recognized the need for military engineers to build an expanding nation’s canals, roads, and harbors. In 1802, he signed a bill creating the military academy at West Point, New York. Jefferson envisioned the academy as a place to educate future engineers. Lewis was a strong advocate of the new military college, and with Henry Dearborn, the secretary of war, he helped ensure that many of its first appointments came from good Republican stock.[16]Crackel, 109.

Notes

| ↑1 | Extracts from Sherman L. Fleek, “The Army of Lewis and Clark,” We Proceeded On, Vol. 30 No. 4, November 2004, 8–14. The original full-length article is available at our sister site, lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol30no4.pdf#page=9 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Army Posters and Prints, history.army.mil/catalog/pubs/21/daposters/21-38.html accessed 30 Nov 2022. |

| ↑3 | Alan R. Millet and Peter Maslowski, For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States of America (New York: The Free Press, 1994), 91; Michael D. Doubler, I Am the Guard: A History of the Army National Guard, 1636–2000 (Washington, D.C.: Department of the Army, 2001), 69–73. |

| ↑4 | The nine young men from Kentucky were John Colter and George Shannon (recruited by Lewis in Pittsburgh) and William Bratton, Joseph Field, Reubin Field, Charles Floyd, George Gibson, Nathaniel Pryor, and John Shields (recruited by Clark in the vicinity of Louisville). Regular army men recruited later in 1803 included John Newman, Joseph Whitehouse, John Collins, Patrick Gass, John Ordway, John Thompson, Peter Weiser, and Alexander Willard. See the The Personnel Plan. |

| ↑5 | Warren W. Hassler, Jr., With the Shield and Sword: American Military Affairs, Colonial Times to the Present (Ames: Iowa State University Press, 1982), 50 and 63. |

| ↑6 | Theodore J. Crackel, Mr. Jefferson’s Army: Political and Social Reform of the Military Establishment, 1801–1809 (New York: New York University Press, 1987), 32–33. |

| ↑7 | Landon Y. Jones, William Clark and the Opening of the West (New York: Hill & Wang, 2004), 12. |

| ↑8 | Gregory J.W. Urwin, The United States Infantry: An Illustrated History, 1775–1918 (New York: Sterling Co., 1991), 33; Francis B. Heitman, Historical Register and Dictionary of the United States Army from its Organization, September 29, 1789 to March 2, 1903, 2 volumes (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1903; reprinted, University of Illinois Press, 1965), 2:562. |

| ↑9 | Jones, 78. |

| ↑10 | The word “chosen” shouldn’t be thought of as synonymous with “elite,” a term associated in today’s military with crack, highly trained units like the Rangers and Special Forces. Clark’s troopers differed from ordinary, musket-toting infantrymen in carrying a specialized weapon—the rifle—and in the marksmanship training required to use it effectively. |

| ↑11 | Jefferson’s fears of a standing army are well known, but militias concerned him, too. “Beware of a military force, even of citizens,” he wrote to a friend in early 1800. (Crackel, 32.) John Randolph, a fellow Republican, referred to his own “dread of standing armies.” (Crackel, 155.) Albert Gallatin, Jefferson’s future treasury secretary, considered “our little army” a “perhaps necessary evil” for defending the frontier, but one whose forces should be garrisoned as far as possible from population centers. Jefferson did have limited military experience, having served at least nominally as a colonel in the Albemarle County militia in the 1770s. Willard Sterne Randall, Thomas Jefferson: A Life (New York: Henry Holt, 1993), 249. |

| ↑12 | Edward M. Coffman, The Old Army: A Portrait of the American Army in Peacetime, 1784–1898 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), 3. |

| ↑13 | Thomas Jefferson to Nathaniel Bacon, May 14, 1801. Albert Ellery Bergh, ed., The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, 20 volumes. (Washington D.C.: The Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association, 1907), 10:261. |

| ↑14 | Donald Jackson, “Jefferson, Meriwether Lewis, and the Reduction of the United States Army,” in James Ronda, ed., Voyages of Discovery: Essays on the Lewis and Clark Expedition (Helena: Montana Historical Society, 1998), 59-61. Of 269 officers on Lewis’s list in 1801, 131 remained on the rolls a year later. See also Lewis’s Report on Army Officers. |

| ↑15 | Millet and Maslowski, 105. Jefferson also downsized the navy. He stopped work on several ships of the line and a dozen or so frigates in favor of a “mosquito” navy of armed sloops. |

| ↑16 | Crackel, 109. |