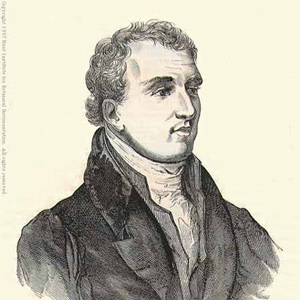

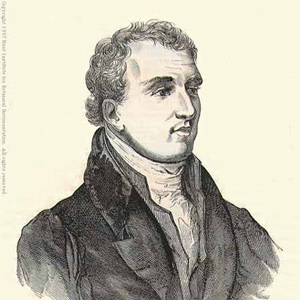

Thomas Nuttall was one of the most adventurous of the early naturalists on the American frontier, and certainly one of most knowledgeable in the field. Gifted as a botanist and ornithologist, skilled as a printer, and a traveler with nerve, he came to the newly formed United States at a perfect time to explorer its expanding boundaries.

Early Years

Born on 5 January 1786 in the village of Long Preston near Craven, Yorkshire, England, he was destined to spend most of his professional life (33 of his 73 years) in America as a botanist, explorer and professor. Nuttall was always willing to take risks. As an example, his career in botany was sparked within a day of his arrival in Philadelphia in 1808 by Benjamin Smith Barton, who had given up on his previous protégé, Frederick Pursh, and was searching for another. He found one in Nuttall, who came inquiring about a plant he had found, a cat-brier, Smilax (SMY-laks) to be exact, and was curious about its name. After some formal instruction in botany from Barton, Nuttall was prepared.

Within months, he was engaged in field work for Barton, collecting plants in the salt marshes of Delaware and the Chesapeake Bay. This 1809 trip was a success, but a second to Lake Ontario in August resulted in illness, and mold destroyed his plants so that he was forced return to Philadelphia.

Nonetheless, Barton asked Nuttall to explore and botanize the Great Lakes region during the summer of 1810. Nuttall’s efforts this time were far more productive, and by mid-August he was at Mackinac Island on Lake Huron, visiting the headquarters of John Jacob Astor’s American Fur Company. There he learned of a trip scheduled to go up the Missouri River the following year. Intrigued, he abandoned Barton’s instructions to return to Philadelphia, and went to St. Louis.

Along the Missouri

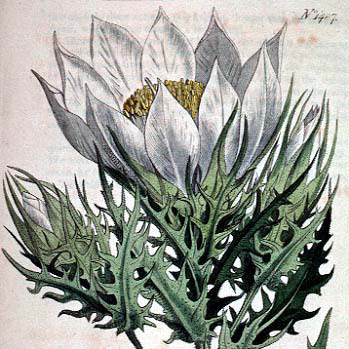

Sego-lily

Calochortus nuttallii Torr. & A. Gray[1]Many of the plants shown here were probably collected by Lewis and Clark in 1805 and were among the cached specimens lost to the disastrous spring floods of 1806. It is difficult to appreciate the … Continue reading

© 2000 James L. Reveal.

Nuttall was a printer by trade, and in St. Louis he applied his skills at a local newspaper, thereby gaining a small but adequate income. He met the Englishman John Bradbury, a fellow botanist, and the two collected locally. In the spring of 1811, they headed up the Missouri River, traveling with the “Overland Astorians” who were heading for Oregon with Wilson Hunt Price as their leader.[2]The story of the “Overland Astorians” was told with considerable relish by Washington Irving in a two-volume 1836 book entitled Astoria. The party left St. Charles, Missouri, on 14 March … Continue reading

Nuttall’s adventures along the Missouri River were many, and the botany intriguing. Although the area had been botanized by Lewis and Clark in 1804, and to a much lesser degree in 1806, none of the plants had been described and thus all was new to him. Nuttall also collected at the perfect time, covering the whole of the river from the Mandan region to St. Louis throughout the growing season. Also, it is good to remember that Lewis and Clark lost their entire 1805 spring collection when a winter cache was destroyed by floodwater. As a result, many of the plants Nuttall (and Bradbury) found were destined to be new to science.

Unlike Bradbury, who returned to St. Louis in July, Nuttall apparently remained on the upper Missouri. It is unclear where he went or how he traveled. One new plant he obtained was the sego-lily, Calochortus nuttallii (kal-oh-COR-tus nut-TALL-ee-eye). Today that plant is found from extreme western North Dakota westward. It is possible Nuttall traveled up river a considerable distance, or that one of the trappers brought the specimen to him. It is likely that Nuttall returned to St. Louis with Manuel Lisa of the Missouri Fur Company, arriving there in late October 1811.

The result for Nuttall was a wealth of new plants, many times more than Barton could ever have expected. In the fall, however, when he got back to St. Louis, Nuttall learned of the possibility of war between England and America. He gave up all hopes of going back to Philadelphia and sailed for Europe from New Orleans, taking his dried plants and seeds with him.

In London, Nuttall prepared his collection, apparently with the intent of delivering a full set of his specimens to Barton. At the same time he published a small pamphlet in association with Fraser’s Nursery, wherein he validly published such new species as the cactus spinystar, Escobaria viviparia (Nutt.) Buxbaum (ess-coe-BAR-ee-ah vi-vi-PAIR-ree-ah,referring to the small, persistent fruits), the alpine golden wild buckwheat, Eriogonum flavum Nutt. (er-ee-AH-gon-um and FLAY-vum, referring to the golden yellow color of the flowers), the tufted evening-primrose, Oenothera cespitosa Nutt. (ee-NO-ther-ah ces-PIT-oh-sah, the matted or tufted habit) and big-fruit evening-primrose, Oenothera macrocarpa Nutt. (ma-crow-CAR-pah, big fruit), the large-flower beardtongue, Penstemon grandiflorum Nutt. (PEN-steh-mun gran-di-FLOOR-um, large flowers), and soapweed, Yucca glauca Nutt. (YUCK-ah and GLAW-cah, alluding to the bluish waxy covering on the leaves).

Suspicions about Pursh

Nuttall had gotten to know Frederick Pursh, and he was decidedly uncomfortable with the man. Nuttall showed some of his new plants to Pursh, who took a rather unprofessional desire to know much more about them. It was Pursh’s opinion that, since he was doing a flora of North America, and had found some (but by no means all) of the same species among the Lewis and Clark material, he should describe all of the new species no matter who found them. Apparently there was some kind of agreement that the two of them would propose Bartonia (bar-TONE-ee-ah) jointly, but Pursh did it without Nuttall, and without Nuttall’s knowledge. Still, Nuttall felt obligated to provide Pursh’s patron, Aylmer Bourke Lambert, with specimens, and thus Pursh had access to most of Nuttall’s new species anyway. This misunderstanding was to play a role in Pursh’s Flora americae septentrionalis.[3]As was common for the day, the pages for Pursh’s Flora were printed in parts, with the printer’s type then reused to print another part. On page 327, or just over half way through the … Continue reading

Nuttall returned to the United States immediately after the conclusion of the War of 1812. From Philadelphia, in 1815, he set off for the field again, this time into the mountains of the Southeast, gathering more new species in areas not yet explored for botanical novelties. In 1817, he published a brief paper on the wild buckwheat genus Eriogonum (from the Greek “erios” and “gonos” meaning “wooly knees,” alluding to the hairs at the nodes in some species), suggesting the genus would be a large one when the American West was finally explored. From the four species he knew, the genus has grown to some 245 species! He also proposed a new genus of plants, Collinsia (cole-IN-zee-ah, named for Zaccheus Collins [1764-1831], a Philadelphia botanist), a genus that eventually would also have several species in the West.

Armed with this new material, Nuttall began to set the type for a new book on the flora of North America in 1817, and on 14 July 1818, the two small volumes of his Genera of North American plants were published in Philadelphia. By the end of the year, Nuttall was on the Mississippi River south of the Ohio heading for the Red River of the south. By boat and foot he made his way to Fort Smith along the Arkansas River, and then southward to the Red, collecting there mainly during the months of May and June of 1819. In July he was along the Verdigris River, and in August and September up the Arkansas well into what is now Oklahoma. In January of the following year he bid goodbye to the Arkansas headed for New Orleans, and from that city sailed back to Philadelphia. In 1821 he published A journal of travels into the Arkansa territory, during the year 1819. While a few of the new species would be named during this period, most were not published until the mid-1830s.

Along the Oregon Trail

In 1825, Nuttall became associated with Harvard University, and likely would have remained a quiet and reclusive professor had not a Boston merchant, Nathaniel Wyeth,[4]Nathaniel Jarvis Wyeth was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1802 into a family of some note, and made his initial fortune by manufacturing ice. Well-liked in Boston, he longed for adventure in … Continue reading brought him a collection of plants in 1833 from the Rocky Mountains with a promise to take him West if he wished to join an expedition to the Columbia River the following year. Nuttall resigned his professorship, prepared the manuscript describing Wyeth’s new plants, and reached St. Louis in March 1834, months before his paper on Wyeth’s 1833 botanical discoveries would be published in Philadelphia.[5]Essentially all of the plants gathered by Wyeth were collected on his return trip in 1833. He left Fort Vancouver, the outpost of the Hudson’s Bay Company, in early February, heading up the … Continue reading

Nuttall’s second trip across the Missouri was his most successful. This time he was traveling in a large company so that transporting his growing collection of dried plants was less of a problem. In addition, he was traveling with a fellow naturalist, twenty-four-year-old John Kirk Townsend,[6]John Kirk Townsend was born in 1809 and died in 1851. He kept an excellent journal and recorded much of the day-to-day activities of his adventure with Wyeth and Nuttall. Townsend re-collected … Continue reading who, like Nuttall, was a skilled ornithologist as well as physician and pharmacist.

From St. Louis, the party headed across Kansas via the Blue River to the Platte, and on into present-day Wyoming, crossing the Continental Divide at South Pass. Wyeth reached the fur trappers’ rendezvous on the Ham’s Fork of the Green River in midsummer. While the trappers traded furs for merchandise, Nuttall and Townsend headed south, collecting even more strange and curious plants on the gumbo-clay hills north of the Utah border. Leaving Wyoming, the party crossed into Idaho and followed the Snake River to the Columbia.

Everywhere Nuttall went he found new and curious plants. Unlike those who came before him, he collected even the unattractive plants—the ordinary things of everyday travel—so that from his collections science came to know sagebrush, Artemisia tridentata (are-tah-MEE-zee-a try-den-TAH-tah, alluding to the shallowly three-lobed leaf), for example, as well as many other nondescript plants of the West.

Nuttall left Oregon and sailed on for Hawaii (and more botanizing) in December 1834 only to return in the spring to continue his collecting efforts. There was not much new to be found, the region having been well collected by David Douglas. He remained in the Pacific Northwest until late in 1835, then caught a ship bound for Philadelphia. After collecting specimens at various California ports, he was found walking the beach in San Diego Bay, collecting shells, by Richard Henry Dana, a former Harvard student who was on his own adventure destined to be told in Two Years Before the Mast.

Academy of Natural Sciences

Lewis collected a specimen along the Lolo Trail, Idaho Co., Idaho, 15 June 1806.

From 1836 until 1841 Nuttall worked at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, making short trips and writing up the hundreds of new species he had found. Articles appeared in the Academy’s journals detailing novelties in various families. Others he sent in manuscript form to John Torrey and Asa Gray for insertion into their newly proposed Flora of North America. Unfortunately, the sudden death of Nuttall’s uncle, and a stipulation in the will that Nuttall spend at least six months of each year in England, forced him to leave America. Except for a brief stay in late 1847 and early 1848, when Nuttall described the last of his American novelties, he remained in Europe.[7]Nuttall published two major papers as a result of his 1834-1836 western trip to the Pacific Coast. His first, “Descriptions of new species and genera of plants in the natural order … Continue reading

Rocky Mountain Iris

Iris missourensis Nutt.[8]Iris missouriensis was originally collected by Lewis in Nevada Valley in what is now Powell Co., Montana. Today, all that remains of his collection are some fragments of the leaves. Wyeth … Continue reading

Photo © 2000 James L. Reveal.

Lewis “saw the common small blue flag” and “preserved speciemines of them” in Nevada Valley, Powell Co., Montana, on 6 July 1806.

Aside from a few matters left unresolved from his earlier travels, the primary reason for returning to the United States was to complete work on his latest project The North American Sylva. Unlike his previous efforts, this was to be a multi-volume, lavishly illustrated set of books that accounted for all of the trees in North America, with special reference to those along the Pacific Coast. Published in three volumes (in 1842, 1846 and 1849) in Philadelphia, the colored lithographs are even today of an excellent quality.

Nuttall’s contributions were many. He wrote papers in geology, botany and zoology—there is still an ornithological society named in his honor—and it is hard to travel anywhere in the American West without seeing a plant that was not named or collected by him.[9]The Nuttall Ornithological Club, centered at Harvard University, began its main publication, Bulletin of the Nuttall Ornithological Club, in 1876. Today, this journal is know simple as The Auk. … Continue reading He was the first to champion the use of a natural system of classification in the United States, he authored a textbook on botany, and his magnificent Silva is difficult to match even today. He was first and foremost a field botanist, and as such changed the direction of botany. After Nuttall, knowledge of the North American flora would come from a combination of field and museum work, not just from old, flat, dried things on a piece of paper collected by someone else.

References

A.M. Coats, 1970. The plant hunters: Being a history of the horticultural pioneers, their quests and their discoveries from the Renaissance to the twentieth century. McGraw-Hill, New York.

R.H. Dana. 1840. Two years before the mast: A personal narrative of life at sea. Harper, New York.

De Voto, B. 1947. Across the wide Missouri. American Book Co., Boston.

Goetzmann, W. J. 1966. Exploration and empire. W. W. Norton & Co., Inc., New York.

Graustein, J. E. 1967. Thomas Nuttall, naturalist. Explorations in America, 1808-1841. Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

Isley, D. 1994. One hundred and one botanists. Iowa State University Press, Ames.

Kastner, J. 1977. A species of eternity. Alfred A. Knopf, New York.

McKelvey, S. D. 1955. Botanical explorations of the trans-Mississippi west, 1790-1850. Arnold Arboretum, Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts.

Nuttall, T. 1818. The genera of North American plants. 2 vols. D. Heart, Philadelphia.

Nuttall, T. 1834. “A catalogue of a collection of plants made chiefly in the valleys of the Rocky Mountains or northern Andes, towards the sources of the Columbia River, by Mr. Nathaniel B. [sic] Wyeth, and described by T. Nuttall.” Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 7: 1-60.

Pennell, F. W. 1936. “Travels and scientific collections of Thomas Nuttall.” Bartonia 18: 1-51.

Reveal, J. L. 1992. Gentle conquest. The botanical discovery of North America with illustrations from the Library of Congress. Starwood Publishing, Washington, D.C.

Reveal, J. L., G. E. Moulton & A. E. Schuyler. 1999. “The Lewis and Clark collection of vascular plants: Names, types and comments.” Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 149: 1-64.

Reveal, J. L. & J. S. Pringle. 1993. “Taxonomic botany and floristics,” pp. 157-192. In: Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.), Flora of North America north of Mexico. Volume 1. Oxford University Press, New York.—See http://www.inform.umd.edu/PBIO/usda/fnach7.html for an online version.

Rickett, H. W. 1950. John Bradbury’s explorations in Missouri Territory. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 94: 59-89.

Townsend, J. K. 1839. Narrative of a journey across the Rocky Mountains, to the Columbia River, and a visit to the Sandwich Islands, Chile, &c., with a scientific appendix. H. Perkins, Philadelphia.

Related Pages

Its oak-strong, hickory-tough wood made powerful, reliable hunting bows. Early French explorers and traders translated its Indian name into bois d’arc,–”wood for a bow,” which was easily anglicized into “bodark.”

“The prickly pear is now in full blume,” he wrote on a mild early-summer day in 1805, “and forms one of the beauties as well as the greatest pests of the plains.”

No other botanical explorer in western North America is more famous than David Douglas. His name is associated with hundreds of western plants, and may also be found on mountains, rivers, counties, schools and even modern-day streets.

There is a great abundance of a species of bear-grass which grows on every part of these mountains,” wrote Lewis on 15 June 1806. “It’s growth is luxouriant and continues green all winter but the horses will not eat it.”

None of the expedition’s journalists made any note of yucca, although in writing of Lemhi-Shoshone Indian dress, Meriwether Lewis mentioned “a small cord of the silk-grass” which at least one scholar has interpreted as referring to the yucca.

Notes

| ↑1 | Many of the plants shown here were probably collected by Lewis and Clark in 1805 and were among the cached specimens lost to the disastrous spring floods of 1806. It is difficult to appreciate the significance the loss of these specimens had on Lewis’s mental state as he was attempting to prepare his final report. The history of botanical collecting in the American West is filled with the names of now forgotten naturalists who lost essentially everything but their lives to fast-flowing water. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The story of the “Overland Astorians” was told with considerable relish by Washington Irving in a two-volume 1836 book entitled Astoria. The party left St. Charles, Missouri, on 14 March 1811 (Nuttall and Bradbury left the following day on foot) and reached the Pacific Ocean on 16 February 1812 after some considerable hardship. Robert Stuart left with a return party in late June of that year and reached St. Louis on 30 April 1813. There is no indication that either botanist desired to go beyond the Knife River Villages of North Dakota. |

| ↑3 | As was common for the day, the pages for Pursh’s Flora were printed in parts, with the printer’s type then reused to print another part. On page 327, or just over half way through the book, Pursh proposes Bartonia ornata (or-NAT-ah, adorned or ornate) as a new name for his own Bartonia decapetala (deck-ah-PET-al-ah, having ten petals) published in Curtis’ Botanical Magazine in 1812. Aside from the fact that the new name was superfluous and not correct according to our modern rules of botanical nomenclature, Pursh adds a comment about Nuttall:In 1812, Mr. Nuttall, on his return from a journey in those parts [the Missouri River], brought seeds and specimens of this and another species to London; and having those means having the living plants, I agreed with Mr. Nuttall to dedicate it to the memory of Dr. B. S. Barton, of Philadelphia, our mutual friend; under which name it was published in the Botanical Magazine. Since that publication, Mr. Nuttall, whose name has occurred in several pages of this work, with all the credit due to his valuable discoveries, has found himself rather offended at not having given him all the exclusive credit of discovery, which with justice and propriety to the memory of M. Lewis, Esq., I never could do.Reveal, Moulton and Schuyler noted in 1999 that after this page, Pursh basically stopped citing Nuttall’s specimens making it difficult to know what Pursh had in hand to describe some of the species. They concluded that Pursh continued to credit Lewis with his discoveries, but non-credited species from the Missouri River were probably all based on Nuttall specimens. |

| ↑4 | Nathaniel Jarvis Wyeth was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1802 into a family of some note, and made his initial fortune by manufacturing ice. Well-liked in Boston, he longed for adventure in the West. He firmly believed that if he could get to Oregon he could become a player in the fur industry, develop farms for growing crops (especially tobacco), and that he could start a salmon industry that would rival the cod industry of New England. To explore the possibilities, he went to Oregon via what would become known as the “Oregon Trail” in 1832, returning the following year. His 1834 trip with Nuttall was not entirely successful. Lacking sufficient financial backing even before he left Boston, his plans in Oregon failed completely due, in no small part, to the loss of a ship sent from Boston to transport goods to and from the Columbia River. Although he failed, Wyeth strongly supported the occupation of Oregon by American settlers, and encouraged many to go west. His own business dealings in Massachusetts remained sound so that he managed to maintain a sizable fortune although he never crossed the Mississippi again. He died in 1856. |

| ↑5 | Essentially all of the plants gathered by Wyeth were collected on his return trip in 1833. He left Fort Vancouver, the outpost of the Hudson’s Bay Company, in early February, heading up the Columbia by boat. By the first week of April he and his party were in Idaho, more or less following the Clark’s Fork of the Flathead River. As may be guessed, the travel was miserable. Once in Montana, the party stopped at Flathead Post (near Eddy, Montana) from 11 to 21 April, and it was here that Wyeth began to seriously collect plants for Nuttall. In May, as more came into bloom, Wyeth collected more frequently when he re-entered Idaho in late May and continued southward to the Ham’s Fork of the Snake River, which he reached in early July. In July, Wyeth stopped at the ninth fur-trapper rendezvous to learn more about the trade, and probably did not collect much after that. He and his men then traveled northeastwardly across Wyoming, followed the Yellowstone to the Missouri, and reached St. Louis in early October. Nuttall probably got the collection in late November and read his paper before the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia on 18 February 1834. He accounted for 113 species. Among the new genera, Nuttall proposed the distinctive sunflower genus Wyethia (wye-ETH-ee-ah) with the wonderful common name mule’s-ear. The paper was formally published 28 October 1834. |

| ↑6 | John Kirk Townsend was born in 1809 and died in 1851. He kept an excellent journal and recorded much of the day-to-day activities of his adventure with Wyeth and Nuttall. Townsend re-collected several of the birds found originally by Lewis and Clark, and found several more that were new. From Fort Vancouver, in 1835, Townsend shipped hundreds of bird and animal specimens to the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. The Academy had provided the ornithologist with a hundred dollars for his travels; today his specimens are priceless. |

| ↑7 | Nuttall published two major papers as a result of his 1834-1836 western trip to the Pacific Coast. His first, “Descriptions of new species and genera of plants in the natural order Compositae” detailed the diverse array of plant found in the sunflower family, Asteraceae (ass-ter-AYE-see-ee). His second paper was on new and rare plants in families of some economic or horticultural importance. Most of his new western plants were described in Torrey and Gray’s A flora of North America—the first effort by American botanists to summarize the plants of the region. When Nuttall returned in 1847-1848, he described a significant collection made by William Gambe, who traveled the Santa Fe Trail from New Mexico to California in 1841. He also added descriptions of many of the new species he had collected in California in 1836 that were still to be published. |

| ↑8 | Iris missouriensis was originally collected by Lewis in Nevada Valley in what is now Powell Co., Montana. Today, all that remains of his collection are some fragments of the leaves. Wyeth re-collected the plant in 1833, probably in Idaho, and Nuttall described it as a new species in 1834. |

| ↑9 | The Nuttall Ornithological Club, centered at Harvard University, began its main publication, Bulletin of the Nuttall Ornithological Club, in 1876. Today, this journal is know simple as The Auk. Nuttall himself published American’s first field manual on birds in two volumes (1831, 1834). John James Audubon named the California dogwood Cornus nuttallii (CORE-nus) for Nuttall in 1838. Audubon also honored Nuttall in 1837 by naming the yellow-billed magpie, Pica nuttalli (PIE-kah), for him, and in 1844 by naming the common poorwill, Phalaenoptilus nuttalli (fill-aye-NAHP-till-us nut-TAHL-li). Nuttall specimens were also used to describe Nuttall’s woodpecker (Picoides nuttallii (pick-OY-deez), a bird known only from California; it was named by William Gambel. For more information, see Early birds. A look at the history of birds and ornithology in California by Harry Fuller at http://www.goldengateaudubon.org/EducationResourcesMerchandise/ggasearlybirds.html |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.