The U.S.-Mexican War

Years 1846 and 1847 had an increase in documented Jean Baptiste Charbonneau sightings. He was a guide for the Mormon Battalion, a unique military unit consisting of regular U.S. Army soldiers and Mormon pioneer army volunteers. Their purpose was to assist General Stephen W. Kearny in the Mexican War—also known as the U.S.-Mexican War. The war had about twenty major battles—none of which the involved the Mormon Battalion—in the present-day American Southwest and Mexico.

Also called to action were members of the St. Louis-based artillery battery under the command of Major Meriwether Lewis Clark—the son of William Clark and Meriwether Lewis‘s namesake. Major Clark and the Missouri volunteers had a major effect on the outcome of the battles fought south of the Rio Grande in present-day Mexico. The war’s outcome via the 1848 Treaty of Hildago resulted in a 25% expansion in U.S. Territories primarily in California, Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, and Utah, including parts of Colorado, Wyoming, and Oklahoma.[1]Sherman L. Fleek, History May Be Searched in Vain: A Military History of the Mormon Battalion (Spokane: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 2008), 29, 338.

General Kearny was ordered to take California and was authorized to recruit any American emigrants he found there. President James Polk also encouraged him to form a battalion of Mormon volunteers:

Col. Kearny was also authorized to receive into service as volunteers a few hundred of the Mormons who are now on their way to California, with a view to conciliate them, attach them to our country, & prevent them from taking part against us.[2]The Diary of James K. Polk During his Presidency, 1845 to 1849, Milo M. Quaife, ed. (Chicago: A. C. McClurg & Co., 1910), 1:444, https://archive.org/details/diaryofjameskpol00polk.

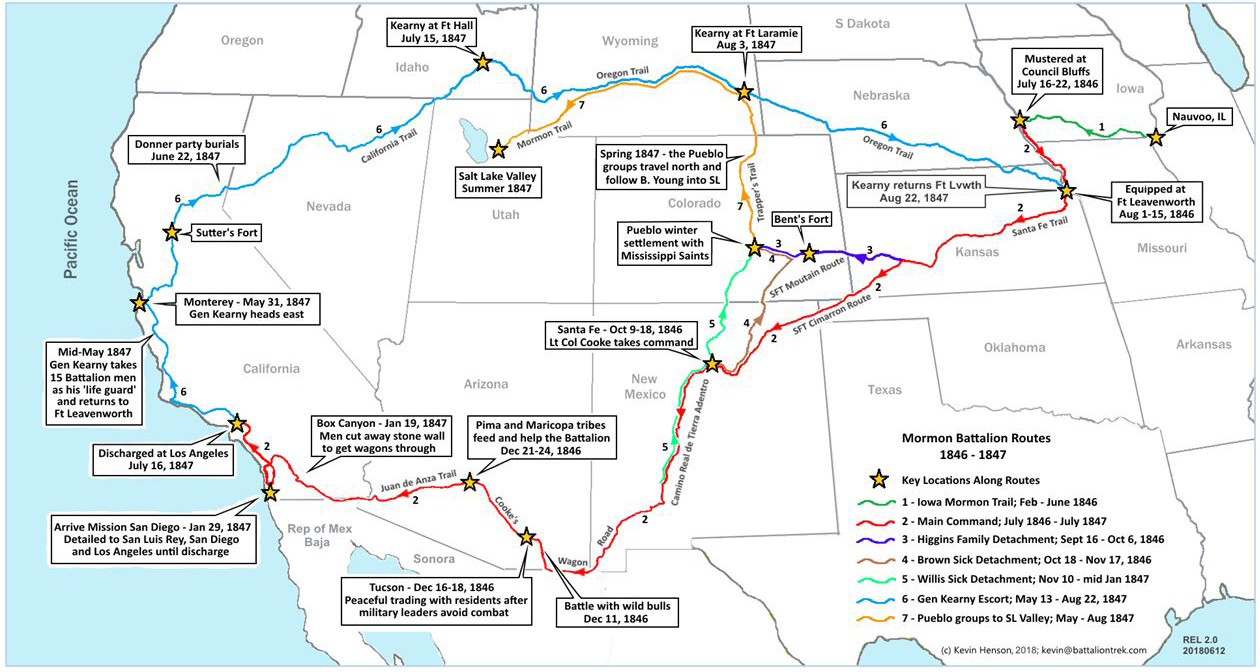

Mormon Battalion Routes 1846–47

By Bud Henson. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Once again, Jean Baptiste was directly involved in a critical period in the history of the American West. Of the many Mormon Battalion routes during the war, Jean Baptiste traveled with Cooke’s main command group, shown above in red as Cooke’s Wagon Road and Juan de Anza Trail. By the time Jean Baptiste joined Cooke’s group, the battalion had been reduced to approximately 340 men and four women.[3]Bud Henson, “Mormon Battalion Routes 1846–1847,” commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mormon_Battalion_Routes_1846-47_HENSON.jpg accessed 22 May 2023.

The Advanced Guard

Prior to Jean Baptiste’s involvement with them, the Mormon Battalion soldiers were recruited and assembled at Council Bluffs in mid-July 1846. They then traveled the Santa Fe Trail with the ultimatum to reach Santa Fe by October 10. Behind schedule, they sent the sick and many of the women to Bent’s Fort, and chose the shorter, but drier, Cimarron route. Cimarrón means bighorn, but the Spanish and Mexicans called the shortcut Jornada del Meurte—Journey of Death.[4]Stanley B. Kimball, Historic Sites and Markers Along the Mormon and Other Great Western Trails (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988), 199.

The march of the Mormon Battalion is unique in that so many participants wrote about it. Among them, Dr. George Sanderson, called by many of the volunteers as Dr. Death for his practice of bleeding and purging dehydrated and overheated soldiers,[5]Fleek, 191, 195. kept an insightful journal. He described a portion of the Cimarron Cut-off experience:

Our teams fail every day. I think this expedition will satisfy our Government that marching an army to Santa Fe California &c is not so easy accomplished as talked about . . . .[6]24 September 1846, “Journal kept by George B. Sanderson, Ast. Surgeon, United States Army from Fort Leavenworth, Missouri, to Santa Fe, New Mexico and to San Diego, Upper California, and back … Continue reading

While the Mormon Battalion rushed to make their Santa Fe deadline, Jean Baptiste was picked up by Kearny’s “advanced Guard of the Army of the West” and assigned to First Lieutenant William Emory, a renowned Army Topographical Engineer, scientist, and explorer. With him were old associates such as Kit Carson and Thomas Fitzpatrick.[7]Fleek, 223–25.

Avery gave this account of Jean Baptiste’s ability to spot potential threats:

October 6.—

I saw some object perched on the hills to the west, which were at first mistaken for large cedars, but dwindled by distance to a shrub. Chaboneau (one of our guides) exclaimed “Indians! there are the Apaches.” His more practised eye detected human figures in my shrubbery. They came in and held a council . . . . [8]William H. Emory, Notes of a Military Reconnaissance, from Fort Leavenworth, in Missouri, to San Diego (Washington: Wendell and Van Benthuysen, Printers, 1848), 52, … Continue reading

The Old Trapper

Beaver Tail

© 2017 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

The Mormon Battalion made their Santa Fe deadline, and Jean Baptiste was sent back to be one of their guides. Their new leader was Lieutenant Colonel Philip St. George Cooke—a gifted military and calvary strategist. Veteran trapper Antoine Leroux would be the lead guide and Dr. Stephen Foster the interpreter. The other scouts were Pauline Weaver, Philip F. Thompson, Willard Hall, Appolonius, Chacon, Francisco, and Tasson.

The nature of the topography made the search for water critical, as described by Cooke:

Leroux, with five, six, or seven others, would get a day in advance, exploring for water, in the best practicable direction; finding a spring or a puddle, (sometimes a hole in nearly inaccessible rocks,) he would send a man back, who would meet me, and be the guide. This operation would be repeated until his number was unsafely reduced, when he would await me, or return to take a fresh departure. This was the plan, but, ever varying and uncertain, attended, of course, with much anxiety.[9]Hamilton Gardner, “Report of Lieut. Col. P. St. George Cooke of his March from Santa Fe, New Mexico, to San Diego, Upper California,” Utah Historical Quarterly,” 22 (1954): 22, … Continue reading

Cooke first met Jean Baptiste on his first day out of Santa Fe, 24 October, near present-day Albuquerque. He declined to follow Jean Baptiste’s suggestion to head south and take a road to El Paso. Leroux arrived on 2 November and also recommended traveling further south rather than follow Kearny’s advanced guard track. This latter advice, Cooke followed.[10]Philip St. George Cooke, “Report and Journal of Lieutenant Colonel Philip Saint George Cooke’s March from Santa Fe, New Mexico, to California, in Command of the Mormon Battalion,” … Continue reading

On 6 November 1846, Dr. Sanderson described the joy of eating a large beaver caught by Jean Baptiste:

We encamped at a beautiful spot, a valley bounded on the West & East by a high bank and gently sloping towards the river. We had a great delicacy for supper. Beaver meat. One of our Guides an old Trapper caught one. It was very fine eating indeed particularly the tail. The meat resembled veal very much. The day as been very warm burning ones face. After enjoying my supper and listening to some tales told by this trapper I went to bed.[11]Sanderson, “Journal,” 24.

Here, Jean Baptiste, Clark’s dancing toddler in 1806, is now an “old Trapper” catching beaver and telling tales at the evening’s camp. Only fellow guide Antoine Leroux had more years trapping in the Rocky Mountain West.

The Grizzled Hunter

After one frustrating day without water, 23 November, Lt. Col. Cooke learned more of Jean Baptiste’s personality. In his 1878 book Conquest of New Mexico and California, Cooke re-tells this incident involving a wayward mule:

Since dark Charboneaux has come in; his mule gave out, he says, and he stopped for it to rest and feed a half an hour; when going to saddle it, it kicked at him and ran off; he followed it a number of miles and finally shot it; partly I suppose from anger, and partly, as he says, to get his saddle and pistols, which he brought into camp.”[12]Philip St. George Cooke, The Conquest of New Mexico and California: an Historical and Personal Narrative (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1878), 131, … Continue reading

One week after shooting his mule, Jean Baptiste’s abilities as a hunter were witnessed by Lt. Col. Cooke and Dr. Sanderson. Prior to crossing the Guadalupe Mountains—the western Continental Divide—they both reported the following hunting incidents, here told by Dr. Sanderson:

I left Camp very e[arly] this morning ahead of the Command in company with one of our guides, a very enterprising daring fellow. He is half Crow Indian. His father a Frenchman. We had not left the camp more than a mile when he crawled some distance towards a very large Antelope and shot it. He had the skin of[f] and cut up I am confident in five minutes.

We tied behind our mules and travelled on about three miles, and in passing through the Mountains saw three Grisly Bears [grizzly bears] a Mother with two Cubs half grown. This man pulls of his coat and hat ties a hander chief around his head and away he starts up the Mountain to shoot them. After a while I heard his Rifle crack twice in succession so quick you would not credit that it was from the same gun. This was one of the most exciting as well as hazardous scenes I ever witnessed. After he shot the first time she immediately made towards him. He shot the second time and what is almost incredible both the Balls entered the same place. The young ones also advanced towards him making the most pitiful bowling and growling. He was found(?) to take to a projecting piece of rock standing bluff of from the side of the mountain. The Cubs kept running backwards and forwards toward the rock where he stood for five minutes which rock was four hundred feet from the base of the Mountain. He shouted be had no more bullets. I felt very much alarmed for his situation. I sent him up some more ammunition but before the man got up the Cubs left the place the Mother dead.[13]Sanderson, “Journal,” 32.

Along the San Pedro

The San Pedro River flows through the Chihuahuan and Sonoran Deserts in southeast Arizona. Near this river, the Mormon Battalion fought off a herd of feral cattle. Of the river, Cooke wrote:

December 9 [1846:] My anxiety was became very great . . . and after ascending a hill saw a valley indeed, but no other appearance of a stream than a few ash trees in the midst; but they, with the numerous cattle paths, gave every promise of water. On we pushed, and finally, when twenty paces off, I saw a fine bold stream.

Two days later, Cooke sent Jean Baptiste to scout the country while his men battled wild attacking bulls:

At 2 o’clock, again I came to a cañon, and several men having been wounded and much meat killed, I encamped, sending Charboneaux to examine the country. He came immediately in view of a deserted “village,” which I presume is the true San Pedro.

There was quite an engagement with bulls, as I had to direct the men to load their muskets to defend themselves.[14]Cooke, “Report and Journal,” 37.

Cooke passed the canyon on December 12 unsure of the best route they should take:

Charboneaux still thinks the gap the one we are to pass, and that it is only accessible for wagons some ten miles lower down; so I have determined to send early in the morning to have the trail followed . . . .[15]Cooke, “Report and Journal,” 36–38.

The Final Push

In present-day Arizona and California, the Mormon Battalion followed the 1774 route of explorer Juan Bautista de Anza Bezerra Nieto (1736–1788). The trail had until the 1820’s been closed by the Quechan [Yuma] tribe. At this point in his life, Jean Baptiste was directly involved with six National Historic Trails: Lewis and Clark, Nez Perce (Nee-Me-Poo), Juan Bautista de Anza, Mormon Pioneer, Oregon, and Santa Fe.

The battalion followed the San Pedro for about fifty miles before turning towards Tucson. Cooke managed to control the Spanish soldiers garrisoned there without any actual battle. After another arduous desert crossing, they reached the relatively verdant Gila River on December 21. A week later, Cooke sent several of his best scouts ahead to get more provisions and mules—by purchase and if necessary by force:

I sent Leroux, Charboneaux, and three other guides express this morning; Mr. Hall went with them. Their instructions were, to proceed with caution when there was any reason to expect to meet Mexican troops, or important parties with droves. To observe any discovered until they passed the southern Sonora road from the crossing of the Colorado; otherwise, to endeavor to inform me of their approach; if strong enough, to seize any drove of mules or horses coming out of California without passport, and bring them to me; one or two to go on, if possible, to bear my letter to General Kearny wherever to be found and; if necessary, one or two of them to examine the road from Warner’s to San Diego, and meet me there to guide me, &c., by the 21st of January. To endeavor to bring me from twenty to seventy fresh mules from the vicinity of Warner’s to the Colorado, (a part of them assisted by hired bands;) and also eight or ten fat beeves.[16]Cooke, “Report and Journal,” 55.

On 11 January, after failing to dig their own wells, Cooke found this note written by Jean Baptiste:

I found here, on the high bank above the well, stuck on a pole, “No water; January 2.—Charboneaux.” This fills me with fearfulness not only for the full success of my party, but almost for their safety, for they had rode their tired animals hard so far, were disappointed for water here, and would be for fifty-seven miles further.[17]Cooke, “Report and Journal,” 69.

Four days later at the Pozo Hondo watering hole in today’s Imperial Valley, Major Cloud returned having traveled to California with Jean Baptiste’s advanced party of scouts. He had delivered Cooke’s letter to General Kearny, and returned with a reply and letters. Later that day, Cooke reports that Tesson—alone—had brought back some mules and cattle, although Cooke seemed disappointed in his effort.[18]Fleek, 308; Cooke, “Report and Journal,” 72.

On 18 January at Vallecito, Cooke learned that the advanced party had arrived at San Diego on 14 January. The Mormon Battalion had now been through the worst, and were beginning to recover:

The men, who this morning were prostrate, worn out, hungry, and heartless, have recovered their spirits tonight, and are singing and playing the fiddle.[19]Cooke, “Report and Journal,” 75.

After two additional days of hard marching, Col. Cooke connected with Jean Baptiste at a deserted Indian village, the latter having left San Diego on the 17th. Jean Baptiste’s journey was not without risk for the governor of San Diego had retained fellow guides Leroux and Hall thinking the road unsafe from Mexican soldiers. One could wonder if Jean Baptiste was sent in hopes that he could pass as a Luiseño or Quechan [Yuma] Indian. Jean Baptiste informed Cooke that it was five days—”some very hard”—to San Diego and recommended taking the left-hand road through San Pascual.[20]Fleek, 308; Cooke, “Report and Journal,” 77.

Cooke then ordered Jean Baptiste and some Indians to have some of the battalion’s cattle taken to Warner Ranch and then gather stray mules and cattle thought to be at San Isabel. The next day, Jean Baptiste left early for San Isabel. By that day’s end, the tired battalion men finally arrived at Warner’s Ranch, which provided food, water, and rest.

On 22 January, Jean Baptiste returned having delegated care of the mules to others, and apparently made a deal to return five previously abandoned wagons. Cooke recorded:

Charboneaux returned this evening, leaving others to do his business; and they have only brought three, of six or seven mules, from San Isabel. “Bill,” the overseer, came with him; and Mr. Stoneman has bargained with him to send for five wagons—the two nearest costing twenty dollars each; he also takes charge of twenty-four of my broken down mules.[21]Cooke, “Report and Journal,” 80.

It is unclear if Cooke is referring to Jean Baptiste or Mr. Stoneman. One interpretation is that Jean Baptiste was tasked with hiring locals to do this work. His multi-lingual communication skills would make him a natural choice to serve as a contractor and supervisor—a middleman between army officers and the local Spanish and Native American inhabitants.

San Luis Rey Mission

Another oasis, San Luis Rey Mission, was reached by the battalion on 27 January. Of the mission, Private Guy Keysor wrote:

The building porches, & railings being of beautiful white gives the edifice a degree of splendour that the traveler’s eye seldom meets with in these western wilds.[22]Quoted in Fleek, 315.

The mission likely impressed Jean Baptiste as well as later in the year, he would be appointed its alcalde.

Final Congratulations

The Mormon Battalion reached San Diego on 29 January. It may not have been the longest march in U.S. military history, but it was likely the most difficult.[23]In response to the 1857 Utah War, the 6th Infantry made a longer march, and the 7th Infantry marched at least as long as did the Mormon Battalion (Fleek, 326). At the end of his official journal, Cooke gave them high praise:

The Lieutenant-colonel commanding congratulates the battalion on their safe arrival on the shore of the Pacific ocean, and the conclusion of the march of over two thousand miles.

History may be searched in vain for an equal march of infantry . . . . Thus, marching half-naked and half-fed, and living upon wild animals, we have discovered and made a road of great value to our country.[24]Cooke, “Report and Journal,” 84.

Companies and detachments were soon assigned various occupation duties throughout southern California before being discharged on 16 July. On January 24, 1848, James Marshall found gold near Sutter’s Mill, an event witnessed and recorded by Mormon Battalion veteran Henry Bigler.[25]Fleek, 375. Jean Baptiste Charbonneau along with many Mormon Battalion veterans were soon to become California gold miners.

Recommended Reading

- Sherman L. Fleek, History May Be Searched in Vain: A Military History of the Mormon Battalion (Spokane: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 2008).

- Philip St. George Cooke, The Conquest of New Mexico and California: an Historical and Personal Narrative (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1878), archive.org/details/conquestofnewmex00cookrich.

- “Journal kept by George B. Sanderson, Ast. Surgeon, United States Army from Fort Leavenworth, Missouri, to Santa Fe, New Mexico and to San Diego, Upper California, and back to the United States in the years 1846 & 1847” [transcript], J. Willard Marriott Digital Library, University of Utah, https://collections.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6rrwwsj.

Notes

| ↑1 | Sherman L. Fleek, History May Be Searched in Vain: A Military History of the Mormon Battalion (Spokane: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 2008), 29, 338. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The Diary of James K. Polk During his Presidency, 1845 to 1849, Milo M. Quaife, ed. (Chicago: A. C. McClurg & Co., 1910), 1:444, https://archive.org/details/diaryofjameskpol00polk. |

| ↑3 | Bud Henson, “Mormon Battalion Routes 1846–1847,” commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mormon_Battalion_Routes_1846-47_HENSON.jpg accessed 22 May 2023. |

| ↑4 | Stanley B. Kimball, Historic Sites and Markers Along the Mormon and Other Great Western Trails (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988), 199. |

| ↑5 | Fleek, 191, 195. |

| ↑6 | 24 September 1846, “Journal kept by George B. Sanderson, Ast. Surgeon, United States Army from Fort Leavenworth, Missouri, to Santa Fe, New Mexico and to San Diego, Upper California, and back to the United States in the years 1846 & 1847” [transcript], J. Willard Marriott Digital Library, University of Utah, page 11, https://collections.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6rrwwsj. |

| ↑7 | Fleek, 223–25. |

| ↑8 | William H. Emory, Notes of a Military Reconnaissance, from Fort Leavenworth, in Missouri, to San Diego (Washington: Wendell and Van Benthuysen, Printers, 1848), 52, archive.org/details/notesamilitaryr01emorgoog. |

| ↑9 | Hamilton Gardner, “Report of Lieut. Col. P. St. George Cooke of his March from Santa Fe, New Mexico, to San Diego, Upper California,” Utah Historical Quarterly,” 22 (1954): 22, issuu.com/utah10/docs/volume_22_1954. |

| ↑10 | Philip St. George Cooke, “Report and Journal of Lieutenant Colonel Philip Saint George Cooke’s March from Santa Fe, New Mexico, to California, in Command of the Mormon Battalion,” National Archives Catalog, Record Group 9436, p. 5, catalog.archives.gov/id/300370; Fleek, 256. |

| ↑11 | Sanderson, “Journal,” 24. |

| ↑12 | Philip St. George Cooke, The Conquest of New Mexico and California: an Historical and Personal Narrative (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1878), 131, archive.org/details/conquestofnewmex00cookrich. |

| ↑13 | Sanderson, “Journal,” 32. |

| ↑14 | Cooke, “Report and Journal,” 37. |

| ↑15 | Cooke, “Report and Journal,” 36–38. |

| ↑16 | Cooke, “Report and Journal,” 55. |

| ↑17 | Cooke, “Report and Journal,” 69. |

| ↑18 | Fleek, 308; Cooke, “Report and Journal,” 72. |

| ↑19 | Cooke, “Report and Journal,” 75. |

| ↑20 | Fleek, 308; Cooke, “Report and Journal,” 77. |

| ↑21 | Cooke, “Report and Journal,” 80. |

| ↑22 | Quoted in Fleek, 315. |

| ↑23 | In response to the 1857 Utah War, the 6th Infantry made a longer march, and the 7th Infantry marched at least as long as did the Mormon Battalion (Fleek, 326). |

| ↑24 | Cooke, “Report and Journal,” 84. |

| ↑25 | Fleek, 375. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.