America’s M.D.

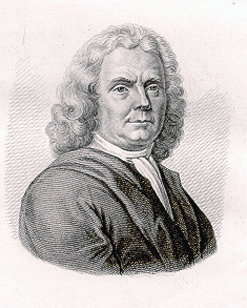

Dr. Benjamin Rush (1746-1813) at age 37

by Charles Willson Peale (1783)

Courtesy Winterthur Museum, gift of Mrs. Julia B. Henry (1959)

Oil on canvas, 55″ by 44½”.

Benjamin Rush was many things: a zealous reformer who advocated constantly for social and educational causes, an ardent patriot who signed the Declaration of Independence and served in the medical department of the Continental Army, a teacher whose influence spread across the growing United States through the thousands of medical students and apprentices he taught, a tireless physician who gave so much to relieve the suffering of his patients that his own health was affected. His roles as reformer, patriot, teacher and physician were informed by a firm Christian faith whose expression may have varied (he never quite settled on one church) but whose conviction never did.

Rush’s energy, dedication, and prolific pen had made him the most famous physician in America in 1803,[1]Richard Shryock, “The Medical Reputation of Benjamin Rush: Contrasts over Two Centuries,” the Fielding H. Garrison Lecture, delivered at the 43rd annual meeting of the American … Continue reading the year Meriwether Lewis visited him in Philadelphia, where Rush, at the behest of Thomas Jefferson, would advise Lewis on how to keep his men healthy and what questions to ask to determine the health practices of the Indians he would encounter.[2]Lyman H. Butterfield, ed., Letters of Benjamin Rush, 2 vols. (Princeton: University Press, 1951). Rush to Thomas Jefferson, 11 June 1803. Hereafter cited as Letters.

The city Lewis visited was the most important in the young nation, full of famous buildings and renowned institutions, an economic, financial, cultural, intellectual, and political center second to none, until 1800 the capital of the nation and still its chief port. Benjamin Rush, as much as even Benjamin Franklin, was a Philadelphian, and should always be viewed as intimately a part of his city.

Childhood

Benjamin Rush was born 4 January 1746 (New Style) in the rural community of Byberry, twelve miles north of Philadelphia.[3]Except as noted, biographical information comes from David Freeman Hawke, Benjamin Rush: Revolutionary Gadfly (Indianapolis and New York: Bobbs-Merrill, 1971) and Nathan G. Goodman, Benjamin Rush, … Continue reading His great-great grandfather, a captain of horse in Oliver Cromwell’s army who had become a Quaker, had settled there in 1683. (Benjamin was baptized an Episcopalian but was mostly raised a Presbyterian.) John, Rush’s father, set up shop as a gunsmith in Philadelphia in 1748, a trade John’s farmer-father had also practiced. When John Rush died in 1751, his wife Susanna firmly established the family in the city, where she opened a grocery and provision store which, together with proceeds from her husband’s estate, provided for her and her children.

The Philadelphia of the 1750s was a growing, tolerant, progressive, somewhat dull city. It had its share of problems. David Freeman Hawke writes,

Hogs ran wild. A constant stench arose from Dock Creek, a stream that twisted through the heart of the city and was flanked by stables and tanyards that used it for an open sewer. Filth accumulated in the streets until heavy rains washed it away. Flies blackened uncovered food, and bedbugs, mosquitoes, and roaches tormented residents through the sweltering summers.[4]Hawke, 9.

A young Rush would have been exposed to the sordid aspects of a bustling port city.

But if Philadelphia was not Eden, it nonetheless had many attractions and amenities.[5]The following information on early Philadelphia comes from Russell F. Weigley, ed., Philadelphia: A 300-Year History (New York and London, Norton, 1982), 1-108. Streets were gradually being paved and wooden sidewalks were common, as were street lights. The city was known for its craftsmen, who produced furniture and other items for the well-to-do. The port connected the city to the rest of the world, providing much of the wealth of the city through trade and exports from the surrounding fertile agricultural area. The port also made Philadelphia more cosmopolitan than other colonial cities. Developments in science and thought came back with Philadelphians who traveled to Europe to study.

Benjamin Franklin’s energy and public-spiritedness set the tone for the city, and greatly improved the quality of life for its citizens. Franklin helped make Philadelphia a center of publishing, and his efforts greatly improved the mail system, connecting the city—and the other colonies—more closely. With Franklin as the guiding spirit, Philadelphia saw many firsts in British North America: the first circulating library (the Library Company, 1731); the first organized fire company (the Union Fire Company, 1736); the first hospital (Pennsylvania Hospital, 1751); the first system of public night watch (1751); the first fire insurance company (the Philadelphia Contributionship, 1752). Franklin also helped organize the first college in the city (now the University of Pennsylvania) in 1755.

Philadelphia was a center of science; again we find Franklin’s presence. The American Philosophical Society (APS) was started by Franklin (and the botanist John Bartram) in 1743, the first scientific society in North America, and which after 1769 began its real emergence as America’s preeminent scientific society, remaining so well into the 19th century. Franklin created much of the scientific reputation of Philadelphia with the publication of his Experiments and Observations in Electricity in 1751, a reputation further cemented internationally by the historically important observation of the transit of Venus in 1769 that was organized by the APS.

Rush grew up in the city—the most urbanized area in the colonies—that Franklin did so much to create, and although very different personalities, they shared similar ideas of active citizenship, constantly striving to improve the self and society. Franklin, too, was to become one of Rush’s mentors.

Calvinist Training

Rush was much more formally educated than the largely self-taught Franklin. At age eight Rush went to a Presbyterian boarding school run by his uncle, Samuel Finley, the first of his father figures and mentors. At the age of thirteen Rush enrolled at the College of New Jersey, now Princeton University, another Presbyterian institution, run by Samuel Davies, who became another mentor.

Finley’s and especially Davies’ institutions formed Rush in several ways. Both men were Calvinists, imbued with the spirit of the Great Awakening, the first major American religious revival. It was begun by George Whitefield, who propagated the view that, as David Freeman Hawke writes, “God offered regeneration to all who opened their hearts to Him, regardless of their race or rank in society”; God’s grace alone, not wealth or power, put humankind on the true road to happiness. “This spiritual happiness gained . . . carried with it public duties,” he wrote; one “must work with god to bring heaven down to earth.”[6]Hawke, 13. This is the deep source of Rush’s reformist impulse, his patriotism, and even his approach to medicine. Restoration of sovereignty to “a free and virtuous people” would allow them to “advance to knowledge and truth according to God’s plan,” resulting in a renewal of Christian civilization.[7]Donald J. D’Elia, “Jefferson, Rush, and the Limits of Philosophical Friendship,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 117, No. 5 (Oct. 25, 1973), 336. As a physician, Rush, following his belief that nature was fallen, did not trust nature to cure disease. Only “heroic” medicine based on a system of medicine in which the physician tries to “conquer nature the way Christ conquered death at Calvary” could cure disease.[8]Ibid.

Redman’s Intern

After some thought about becoming a lawyer, Rush followed Finley’s advice and took up medicine. Dr. John Redman, considered the best physician in Philadelphia, a friend of Finley’s and another Presbyterian, in 1761 accepted Rush as an apprentice. Only 15, Rush went quickly to work, mixing drugs (a job of physicians at the time), accompanying Redman on patient visits and keeping the books.

Lifelong habits of long hours, no distractions from work, and intellectual improvement were solidified during Rush’s five years with Redman. Rush writes in his autobiography:

During this period I was absent from [Redman’s] business but eleven days, and never spent more than three evenings out of his house. . . . It may not be amiss to mention here that before I began the study of medicine, I had an uncommon aversion from seeing such sights as are connected with its practice. But a little time and habit soon wore away all that degree of sensibility which is painful, and enabled me to see and even assist with composure in performing the most severe operations in surgery. The confinement and restraint which now imposed upon me gave me no alternative but business and study, both of which became in a short time agreeable to me. I read in the intervals of my business and at late and early hours, all the books in medicine that were put into my hands by my master, or that I could borrow from other students of medicine in the city.

He was learning his profession—and further developing his close ties to the life of his city.[9]George W. Corner, ed. The Autobiography of Benjamin Rush: His “Travels Through Life” Together with his “Commonplace Book” for 1789-1813, Princeton, Princeton University Press, … Continue reading

Edinburgh Medical School

Although Rush was committed to Philadelphia (and not prudish), he was contemptuous and weary of sinful city life. The serious young man wrote his friend Ebenezer Hazard,

Vice and profanity openly prevail in our city. Our Sabbaths are boldly profaned by the most open and flagitious enormities. Our Young men in general (who should be the prop of sinking Religion) are whole devoted to pleasure and sensuality and very few are solicitous about the one thing needful.

O my dear Ebenezer, let not the deadly contagion reach us. We wrestle with powerful corruptions and temptations, but let us derive strength from the Rock of Ages.[10]Rush to Ebenezer Hazard, Letters, 2 August 1764.

Certainly Rush was aware of stench and filth of the city (and learned that “miasma” in the air caused disease). But Rush knew also that Philadelphia was a dynamic place. Later in life, when he had become part of the establishment, Rush could write, “From habit, from necessity, and from local circumstances, all the States view our city as the capital of the new world.”[11]Rush to Noah Webster, Letters, 13 February 1788.

As much as Philadelphia had to offer, its medical school was yet new and so, like a number of his contemporaries, Rush went to Edinburgh—the most prestigious medical school in Europe—to get a medical degree. In Edinburgh Rush received training from such luminaries as the anatomist Alexander Monro; the chemist Joseph Black, the discoverer of carbon dioxide; and William Cullen, who taught theory and practice of medicine. Rush would leave Edinburgh a disciple of Cullen’s theories.

In Edinburgh, Rush socialized, with notable success, with members of the Scottish elite. After graduating in 1768, he spent the following year in London and Paris furthering his training and meeting many notables. In London Rush took clinical training with Richard Huck and attended lectures by the anatomist William Hunter. Through Huck, Rush met Sir John Pringle, physician to the royal family. Rush also met Dr. John Fothergill, a Quaker and friend of many Americans. Rush’s most enduring friendship was with Dr. John Coakley Lettsom, a man as idealistic and energetic as Rush. Among the notables Rush met were Samuel Johnson, Oliver Goldsmith, and painters Benjamin West and Sir Joshua Reynolds. Another significant acquaintance, first begun in Edinburgh, was with George Whitefield, the great preacher who had so much influenced Finley and Davies.

Franklin, who had helped Rush with introductions for Edinburgh, showed him around London as well or, as Rush puts it, he was “domesticated in [Franklin’s] family.” One time Franklin took Rush to Court, pointing out the distinguished “public characters” of the nation.[12]Autobiography 55. Planning to go to Paris, Rush was assisted by Franklin again, who wrote other introductions and provided a letter of credit. The money Rush used was repaid from some of the first money he made upon his return to America.[13]Goodman, 19.

His European experience gave Rush an intellectual grounding, social polish, and medical knowledge only a few in America could match.

Building a Practice

Upon returning to Philadelphia, Rush began practicing medicine. While he could also cultivate wealthier clients, as he did among fellow Presbyterians, it was first among the poor that Rush built his reputation. As Hawke notes, “His natural courtesy and kindness, his unfeigned sympathy for the distressed, won a wide following among the city’s less prosperous.”[14]Hawke, 85. In Rush’s words:

From the time of my settlement in Philadelphia in 1769 ’till 1775 I led a life of constant labor and self-denial. My shop was crowded with the poor in the morning and at meal times, and nearly every street and alley in the city was visited by me every day. There are few old huts now standing in the ancient parts of the city in which I have not tended sick people. Often have I ascended the upper story of these huts by a ladder, and many hundred times have been obliged to rest my weary limbs upon the bedside of the sick (from the wont of chairs) where I was sure I risqued not only taking their disease but being infected by vermin. More than once did I suffer from the latter.[15]Autobiography, 83-84.

Conscientious, charging what he thought a patient could pay (often nothing), Rush soon developed a reputation that in a while begat other business.[16]Quoted in Hawke, 85. While he would eventually become an elite physician, successful in many endeavors, Rush was, and would remain, intimately connected to his city, familiar with all aspects of its life.

A key to Rush’s success was his appointment to the faculty of the College of Philadelphia as professor of chemistry, the first in British North America. Professorships were not well paid but were prestigious; Rush’s name would become better known through his institutional connection. His lectures were reworkings of Black’s from Edinburgh, and Rush never made an important contribution to chemistry. Later he held other appointments, especially as professor of the theory and practice of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, successor institution to the College of Philadelphia, where his influence was vast. Rush’s son James estimated that his father taught nearly 3,000 students between 1779 and 1812.[17]Goodman, p. 132.

Even early in his career, Rush attracted controversy. Opinionated, not shy of expressing himself, he alienated the medical establishment, many of whom practiced medicine according to the theories of Herman Boerhaave, by advocating Cullen’s system of medicine. Boerhaave (1668-1738) was a towering figure, a major medical theorist who was accomplished in other fields as well, including botany and chemistry. To sum up the controversy in very general terms, Boerhaavists were more supportive of the theory of humors and therapeutic bloodletting than Cullenists, who were solidists and much less supportive of bloodletting. That Rush began his career as an advocate of limited bloodletting is certainly ironic.[18]Humoral theory traces back to Hippocrates and Greek medicine. In outline the theory states that disease stems from an unbalance of fluids in the body, the four humors being yellow bile, black bile, … Continue reading

Reformer

Dr. Benjamin Rush established a garden of medicinal plants such as this one in the dooryard of the College of Physicians. Not an academic institution but an association of professionals with common interests and objectives, the College of Physicians of Philadelphia was founded by Dr. Benjamin Rush in 1787. Even though the first medical school in the U.S. had been established in 1765 at what was to become the University of Pennsylvania, and although a medical degree from Edinburgh or London was considered the touchstone of legitimacy for Philadelphia physicians, no formal training was in fact required in order to represent oneself as a doctor, and a period of apprenticeship to one so declared was not necessarily enhanced by formal lectures on “physik.”

Therefore, in part, Rush’s “Discourse Delivered Before the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, 6 February 1787, On the Objects of Their Institution,” stated:

By assuming the name of a College, we shall 1st, be able to introduce order and dignity into the practice of physic, by establishing incentives and rewards for character. Men are generally anxious to preserve the good opinion of those with whom they are obliged to associate. The reception we shall meet with from each other in our meetings will serve to correct or to improve our conduct. And if we are as chaste as we should be, in the admission of members, a fellowship in our College will become in time, not only the sign of the ability, but an introduction to business and reputation in physic. . . .

3dly. By means of our association, under the title of a College, we shall be better able to attract the attention of the government of our country, in matters that relate to the health and happiness of our fellow citizens. . . .

4thly. By stated meetings as a College, we may promote enquiries and observations upon the prevailing diseases of the city. Here the timid may be encouraged, and the sanguine may be taught to doubt. Here the young practitioner may profit by the experience of the old, and the old by the boldness of enquiry, and modern improvements of the young.

Thus the historic College of Physicians of Philadelphia was in a sense a progenitor of the American Medical Association, an organization devoted to the exchange of medical information and practice. One of the ironies of history is that the author of the statements, Benjamin Rush, had by 1803 withdrawn from the College’s membership.

—Charles Reed

Promoting reform was one means to build a more perfect country. While Rush remained throughout his life above all else a physician, his energy, ambition, zeal, and talents were such that he became an advocate for many causes. Franklin was certainly the great example of active citizenship, dedicated to making life better for people everywhere. Rush, also a believer in active citizenship, was more religious and parochial than Franklin, believing that it was America’s destiny to be a freer, more just, and more godly society than any other known to history—a millennial patriotism built on the faith in the perfectibility of man.

Temperance became one of Rush’s causes. His most famous essay is probably An Enquiry into the Effects of Spirituous Liquors upon the Human Body.[19]Philadelphia: Thomas Bradford, [1784?] As much a medical essay as a temperance one, it details the effects of distilled spirits, describing their physiological effects as if he were doing so from a pulpit. One should keep in mind, however, that Rush was not a tee-totaler. Wine and beer were acceptable with meals and, indeed, beer was considered to be nourishment. It was hard liquor that destroyed bodies and souls.

Rush was also an advocate for educational reform. In an address titled “Thoughts Upon Female Education” (1787) he advocated education for girls and young women. While the address envisioned education as preparing females to be good wives and mothers, it was progressive for the time, insisting, for instance, that “our ladies should be qualified to a certain degree by a peculiar and subtle education, to concur in instructing their sons in the principles of liberty and government,” that is, women need to be educated citizens, too, at least so they can instruct their sons.[20]Quoted in Goodman, 314. Rush also wrote against corporal punishment in schools, in favor of a national university, and using the Bible as a textbook. Probably his most lasting contribution to education in America was the key role Rush played in founding Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

An early example of Rush’s strong belief in social justice is his anti-slavery essay, An Address to the Inhabitants of the British Settlements in America, upon Slave-Keeping (1773). In it, he attacks the moral grounds of slavery, saying, for instance, that the vices supposedly characteristic of Negroes—idleness, theft and treachery—”are the genuine offspring of slavery” and not the result of their blackness or any natural inferiority.[21]Quoted in Hawke, 105. There are also horrific accounts of slave life in the West Indies (although Rush never visited the islands). The essay naturally angered slaveholders, though Rush himself owned a slave, whom he freed in 1794. He also became actively involved in abolition, serving as president from 1803 to 1813 of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, aiding the free black community and assisting with the establishment of the African Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia.

Politician

A characteristic belief in the equality of all men (and, more so than almost all Revolutionary leaders, women) led Rush to a faith in the future of a united America more quickly than many of his contemporaries. Indeed, from his return from Europe he was convinced of the corruption of Parliament and the king’s advisors. Rush was pro-independence and during and immediately after the War tended to be a Federalist, favoring a strong Constitution. At the time of the First Continental Congress, Rush was peripheral to it but well-informed, becoming friends with, among others, John and Samuel Adams, George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. During the Second Continental Congress of 1775, though not yet a member, Rush urged the appointment of Washington as Commander of the Army. The doctor also accepted the position of physician-surgeon of the fleet of galleys built to protect Philadelphia from a British invasion up the Delaware River. During this year he also greatly aided the patriots’ cause by helping Thomas Paine get Common Sense printed; it was in fact Rush who suggested the title.

The year 1776 was Rush’s glory year as a politician. Although his exact role is somewhat obscure, Rush was an important figure in pushing Pennsylvania into supporting independence. The Pennsylvania Assembly, made up largely of Reconciliationists, attempted to thwart the so-called Independents. Rush was a member of a committee of Independents that had tried and failed to wrest control of the Assembly from the Reconciliationists. Delegated from the committee to a Provincial Conference to establish a constitution for Pennsylvania, Rush helped draw up plans for a convention that would develop one. At the same time the Continental Congress was voting in favor of the Declaration of Independence. Pennsylvania’s constitutional Conference, usurping the power of the Assembly, met in mid-July, and Rush, resigning as fleet-surgeon, was elected to the new Pennsylvania delegation to the Continental Congress. Rush, who was not in Congress when independence was being debated, nevertheless by happenstance became a signatory of the Declaration, which was signed on about August 1.

Army Doctor

Over the next few months, Rush remained heavily involved in Revolutionary events. He saw action during the fighting around Trenton. About a week after the famous surprise attack, Rush attended to the wounded following a skirmish at Trenton and went to Princeton immediately after the battle there, where he cared for, among others, General Hugh Mercer. The first-hand experience of battlefield medicine gave Rush additional insight into the inadequacies of army medical care (he was already involved in army medical organization through his work in Congress). A few months after his departure from Congress, Rush was appointed physician general for the mid-Atlantic states. Just before the appointment Rush had written an essay on the health of soldiers, a piece containing many sound points about military hygiene. “The mortality from sickness in camps is not necessarily connected with a soldier’s life,” Rush wrote.[22]Quoted in Hawke, 193. The title of the essay was “To the Officers in the Army of the United American States: Directions for Preserving the Health of Soldiers,” printed in the Pennsylvania … Continue reading Filth-caused disease killed more soldiers than battle. Officers should keep their men well-fed, clean and dry. Advice in the essay would be given to Meriwether Lewis in 1803.

The press of events found Rush with the army again, this time at the Battle of Brandywine. A flag of truce to treat wounded allowed Rush to observe conditions in the British army, which intensified his anger about the conditions in the American army, as Washington’s defeat had intensified Rush’s lack of confidence in the American general. He demanded a congressional inquiry into director general William Shippen’s handling of the medical department, which Rush received, but in the event Shippen retained his position and Rush resigned. He had not helped his case by writing an indiscreet letter to Patrick Henry, disparaging Washington’s leadership. Unfortunately, Rush had also praised members of the Conway Cabal who attempted to replace Washington with Thomas Conway as Commander in Chief. (No direct evidence links Rush to the Cabal, and in later years Rush again came to admire Washington.) Rush’s zeal and commitment to the cause, his outspokenness and lack of discretion, and his personal animosity towards Shippen, were contributing factors in Rush’s resignation from the medical department and the damage to his reputation caused by the controversies.

While he remained closely in touch with events, Rush lessened his direct involvement after 1777. He testified at the court-martial of nemesis William Shippen, locked in a bitter dispute with John Morgan (Shippen was acquitted). Another political issue was the Pennsylvania state constitution. At first a supporter, Rush became an ardent foe of its unicameral legislature and weak executive. Rush worked on its modification until a new state constitution was promulgated in 1789. Rush, however, while ever the reformer and writer, was mainly occupied with his practice, his teaching, and his family. Julia Stockton had become Mrs. Rush in January 1776; their first child was born the following year.

APS Member

While the APS dates its founding to 1743, it wasn’t until 1769 that a permanent society emerged from the union of two societies: the American Society for Promoting and Propagating Useful Knowledge and a revived APS.[23]The original APS founded by Franklin in 1743 became dormant in 1746. A similar organization formed in about 1750, calling itself the Young Junto, emulating Franklin’s 1727 group of learned … Continue reading The united society was (and is) officially called the American Philosophical Society, held at Philadelphia, for Promoting Useful Knowledge. “Useful Knowledge” was seen as seeking to understand how the world was organized and functioned, and putting that knowledge to use so that the lives of citizens could be improved. The political situation had provided an impulse to better define the goals of the Society. The Stamp Act and Townshend Acts caused Americans to think about how the colonies could be made less economically dependent upon England. Improvement in agriculture and manufacturing as well as developing trade and commerce now more urgently needed discussing.[24]Bell, Patriot Improvers, Vol. One, 339. Native ground would be the focus, from examining mineral deposits to surveying plants to improving transportation to understanding Native Americans. When Lewis and Clark went up the Missouri in 1804, their mission—equally scientific, economic, ethnographic, geographical, and political—harmonized with the stated purpose of the APS.

While in Europe in 1768, Rush had been elected a member of the American Society, so thus became a member of the united society. On his return he immediately began attending meetings, becoming an active member. He served on various committees, such as the standing Committee on Natural History and Chemistry and the ad hoc committee to design the seal. (With a few modifications, the seal is still used today.) He served as curator (1770-72), secretary (1773-76), vice-president (1797-1800), and councilor (1786-1794, 1806-1813). “Between 1770 and 1797 he delivered fifteen papers and orations before the Society,” many published in the Society’s Transactions. See Rush’s Writings for the APS for a full list of Rush’s orations and publications.[25]Lyman H. Butterfield, “Benjamin Rush as a Promoter of Useful Knowledge,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 92, no. 1, March 1948, 28.

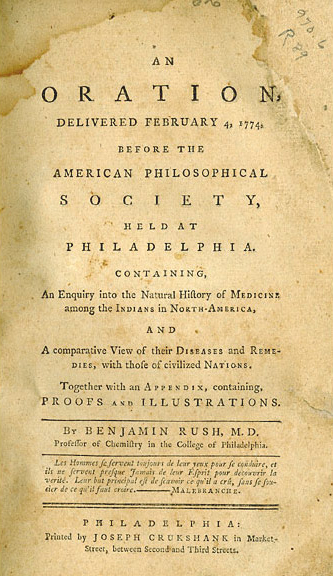

Medicine among the Indians

Some presentations find echoes in the scientific concerns of the Lewis and Clark expedition: a piece on the medicinal qualities of a plant (thorn apple), the effects of cold on the body, the (supposed) mineral springs of Philadelphia. One of Rush’s earliest contributions was an oration on medicine among the Indians, given in 1774. It is no great contribution to medicine or ethnography. Rush had no direct knowledge of Native Americans, instead relying on second hand sources and reports from Edward Hand, a military surgeon who studied Indian life while stationed at Fort Pitt. What Rush does do is present Native Americans not as noble savages but as a people (he does not distinguish among tribes) with a specific way of life. Indian medicine is seen as inferior to western, but Rush points out how disease and corrupting vices have harmed Native Americans—problems western medicine should now address.

Ultimately, the essay is a muddle, filled with material irrelevant to the title. But Rush knew his audience and the pervading American hope for the future. He concluded:

It reflects equal honor upon our society and the honourable assembly of our province, to acknowledge, that we have always found the latter willing to encourage their patronage, and reward their liberality, all our schemes for promoting useful knowledge. What may we not expect from this harmony between sciences and government! Methinks I can see canals cut—rivers once impassable rendered navigable—bridges erected—and roads improved, to facilitate the exportation of grain.—I see the banks of our rivers vieing in fruitfulness with the banks of the rivers of Egypt.—I behold our farmers, nobles—our merchant princes.—But I forbear—Imagination cannot swell with the subject.

I beg leave to conclude, by deriving an argument from our connection with the legislature, to remind my auditors of the duty they owe to the society. Patriotism and literature are here connected together; and a man cannot neglect the one, without being destitute of the other. Nature and our ancestors have completed their work among us; and have left us nothing to do, but enlarge and perpetuate our own happiness.[26]Quoted in Bell, Patriot Improvers, Vol. One, 456. There is, however, no record in the APS manuscript minutes (Archives I, #4 and #5) of Rush attending a meeting of the APS after 1801. In the one … Continue reading

It is with such hopes that Jefferson dispatched Lewis and Clark.

Final Thoughts

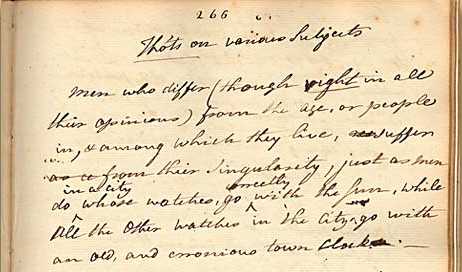

Transcript:

Tho’ts on various Subjects

Men who differ (Though right in all their opinions) from the age, or people in, & among which they live, suffer from their Singularity, just as men do in a city, whose watches go meetly with the sun while all the other watches in the city go with an old, and erronious town clock.

After 1803, Rush had ten years of life left. He spent those years in Philadelphia, still arguably the most important city in America, even as economic power was shifting to New York City and political power to the new federal capital, Washington. Although less politically active than in the 1770s and ’80s, Rush continued as he had throughout his life, advocating causes, and especially practicing, writing about, and teaching medicine. He always gave unstinting care to his patients. Few forgot him as a professor of medicine, and his influence was wide. An unpublished set of lecture notes taken by William Darlington attests to Rush’s effectiveness as a teacher. While discussing “autumnal fever,” Rush used the case of:

A young lady [who] was once in this city affected with autumnal fever, and in her convalescence her moral faculty was much impaired—so that she would tell great falsehoods—she was cured by exercise, cool air, &c. of her fibbing propensity—. This we should remember for the encouragement of relatives.[27]William Darlington, Notes Taken from the Lectures of Benjamin Rush, M.D. on the Theory & Practice of Physic, v. 3, 1803-4, 193. College of Physicians of Philadelphia manuscript number 10a/105. … Continue reading

The passage has an unmistakable charm and is as close as Rush ever got to the humorous.

Benjamin Rush died in 1813 at the age of 67. He was the type of man who attracted adjectives: hard-working, well-mannered, honest, public-spirited, contentious, self-righteous, passionate, studious, unaffected, indiscreet, unbalanced, intelligent, impatient, compassionate, stubborn, articulate, devout, energetic. He seems above all a man who cared about other human beings and gave of himself so that earth would be a better place. As a physician, politician, and writer he was a man of his times who nevertheless worked for a better future. Despite his failings, his was a life of noble effort.

Related Pages

Treatment emphasized depletion of ‘morbid excitement’ through bleeding and purging. Calomel and jalap were preferred purgatives; blended together they became Rush’s pills, taken along by the Corps of Discovery.

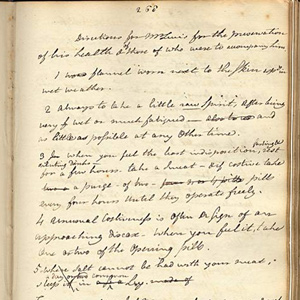

Rush’s Rules of Health

July 27, 1805

Naming the three forks

Lewis and the boats reach the end of the Missouri. After exploring the Madison River, Clark’s group returns to the headwaters, and the captains name the three forks: Jefferson, Madison, and Gallatin.

Rush’s Writings for the A.P.S.

A list of Rush’s writings for the American Philosophical Society (from Lyman H. Butterfield, “Benjamin Rush as a Promoter of Useful Knowledge,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 92, no. 1, March 1948, 35-6.)

Dr. Rush had expressly indicated to Lewis that when one of his men showed the “sign of an approaching disease . . . take one or two of the opening pills” nicknamed “Rush’s Thunderbolts.”

The advice Dr. Rush had given Lewis often sounds rather odd or useless by modern standards, and wasn’t followed to the letter by the captains, but it fulfilled Jefferson’s request.

Rush’s Questions for Indians

Vices, morals, and religion

Benjamin Rush provided Lewis this list of questions about Indian medicine, vices, and religion.

Notes

| ↑1 | Richard Shryock, “The Medical Reputation of Benjamin Rush: Contrasts over Two Centuries,” the Fielding H. Garrison Lecture, delivered at the 43rd annual meeting of the American Association of the History of Medicine, 2 April 1970, printed in Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 45:6 (1971), 507-552. See 516-519 for Rush’s medical reputation. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Lyman H. Butterfield, ed., Letters of Benjamin Rush, 2 vols. (Princeton: University Press, 1951). Rush to Thomas Jefferson, 11 June 1803. Hereafter cited as Letters. |

| ↑3 | Except as noted, biographical information comes from David Freeman Hawke, Benjamin Rush: Revolutionary Gadfly (Indianapolis and New York: Bobbs-Merrill, 1971) and Nathan G. Goodman, Benjamin Rush, Physician and Citizen, 1746-1813 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1934). A comprehensive bibliography of works by and about Rush was published 1998: Claire G. Fox, Gordon L. Miller, Jacquelyn C. Miller, Benjamin Rush, M.D.: A Bibliographic Guide. Bibliographies and Indexes in American History Number 31, Westport, Connecticut & London, Greenwood. |

| ↑4 | Hawke, 9. |

| ↑5 | The following information on early Philadelphia comes from Russell F. Weigley, ed., Philadelphia: A 300-Year History (New York and London, Norton, 1982), 1-108. |

| ↑6 | Hawke, 13. |

| ↑7 | Donald J. D’Elia, “Jefferson, Rush, and the Limits of Philosophical Friendship,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 117, No. 5 (Oct. 25, 1973), 336. |

| ↑8 | Ibid. |

| ↑9 | George W. Corner, ed. The Autobiography of Benjamin Rush: His “Travels Through Life” Together with his “Commonplace Book” for 1789-1813, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1948 (Vol. 25 of the Memoirs of the American Philosophical Society), 38. |

| ↑10 | Rush to Ebenezer Hazard, Letters, 2 August 1764. |

| ↑11 | Rush to Noah Webster, Letters, 13 February 1788. |

| ↑12 | Autobiography 55. |

| ↑13 | Goodman, 19. |

| ↑14 | Hawke, 85. |

| ↑15 | Autobiography, 83-84. |

| ↑16 | Quoted in Hawke, 85. |

| ↑17 | Goodman, p. 132. |

| ↑18 | Humoral theory traces back to Hippocrates and Greek medicine. In outline the theory states that disease stems from an unbalance of fluids in the body, the four humors being yellow bile, black bile, phlegm, and blood. The four humors could be correlated with the four temperaments (choleric, melancholic, phlegmatic, and sanguine), the four elements (fire, earth, water, air), and the four qualities of nature (dry, cold, moist, and hot). Solidists postulated that disease was sited in the solid tissue of the body—in Cullen’s case, the brain and arteries. Roy Porter, The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity, New York and London, Norton, 1997, 56-9; Lester King, The Medical World of the Eighteenth Century (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1958), 140; Richard H. Shryock, Medicine and Society in America: 1660-1860 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1972), 68. |

| ↑19 | Philadelphia: Thomas Bradford, [1784?] |

| ↑20 | Quoted in Goodman, 314. |

| ↑21 | Quoted in Hawke, 105. |

| ↑22 | Quoted in Hawke, 193. The title of the essay was “To the Officers in the Army of the United American States: Directions for Preserving the Health of Soldiers,” printed in the Pennsylvania Packet, 22 April 1777. |

| ↑23 | The original APS founded by Franklin in 1743 became dormant in 1746. A similar organization formed in about 1750, calling itself the Young Junto, emulating Franklin’s 1727 group of learned tradesmen called the Junto. In 1766 the Young Junto changed its name to the American Society for Promoting and Propagating Useful Knowledge, meeting in Philadelphia. The American Society was developing into a growing concern when some former members of the original APS who had not been elected to the American Society revived that organization. Having two scientific societies in a city the size of Philadelphia was not a viable proposition, so the two societies merged in 1769. In addition, in 1766 the Philadelphia Medical Society was founded, which merged with the American Society in 1768. Rush was elected to both the Medical Society and the American Society in 1768, becoming an APS member upon the merger of the societies. For a brief history of the societies, see the two volumes of biographical portraits of members by Whitfield J. Bell, Jr., Patriot Improvers: Biographical Sketches of Members of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. One, 1743-1768 (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1997), and Vol. Two, 1768 (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1990). |

| ↑24 | Bell, Patriot Improvers, Vol. One, 339. |

| ↑25 | Lyman H. Butterfield, “Benjamin Rush as a Promoter of Useful Knowledge,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 92, no. 1, March 1948, 28. |

| ↑26 | Quoted in Bell, Patriot Improvers, Vol. One, 456. There is, however, no record in the APS manuscript minutes (Archives I, #4 and #5) of Rush attending a meeting of the APS after 1801. In the one clear reference as to why he ceased attending meetings, Rush says that he did so to “avoid insult” from “most of my medical brethren.” One can surmise that the animosity from the fierce debates about yellow fever had, at least to Rush, not fully abated. |

| ↑27 | William Darlington, Notes Taken from the Lectures of Benjamin Rush, M.D. on the Theory & Practice of Physic, v. 3, 1803-4, 193. College of Physicians of Philadelphia manuscript number 10a/105. Autumnal fever was literally an affliction of autumn. Rush believed one of the symptoms of a type of autumnal fever was an impairment of the moral sense. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.