As Meriwether Lewis prepared for the great expedition, Thomas Jefferson took a moment to let him know this was not the first time he had tried something like this. In an 27 April 1803, letter, the President told Lewis that a “considerable portion of [the instructions were] being within the field of the Philosophical Society, which once undertook the same mission.” That mission, with its twists, turns, and tales of covert operations, is the subject of our story here.[1]This article is from Lee Alan Dugatkin, “André Michaux’s ‘Almost Expedition’ to the West in 1793,” We Proceeded On, Vol. 47 No. 1, January, 2022, 5–11. The original … Continue reading.

First Two Attempts

George Rogers Clark

By Hermon Atkins MacNeil

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HMcNeil-GRClark.jpg>. Permission via the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Hermon Atkins MacNeil’s list of works include the Standing Liberty Quarter minted between 1916 and 1930, Civil War Soldier’s Monument (Philadelphia, 1921), “Coming of the White Man / Chief Multnomah “, Jacques Marquette bas-reliefs (Chicago, 1894), and the Pony Express Monument (St. Joseph, 1940).[2]“Hermon Atkins MacNeil,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hermon_Atkins_MacNeil accessed on 9 February 2021.

As early as 1783, Jefferson was growing leery of British expeditions in the West: “they pretend it is only to promote knowledge,” he wrote George Rogers Clark, “[but] I am afraid they have thoughts of colonizing into that quarter.” And so he asked Rogers Clark if he might be keen to lead an expedition to the West. “Your proposition respecting a tour to the West and Northwest of the continent would be extremely agreeable to me,” Rogers Clark replied, but monetary circumstance would not allow it, as “I have late discovered that I knew nothing of the lucrative policy of the world.”[3]Jefferson to George Rogers Clark, 4 December 1783, founders. archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-06-02-0289; George Rogers Clark to Jefferson, 8 February 1784, … Continue reading

A few years later, Jefferson was again working to facilitate an exploration of the uncharted West, this time by John Ledyard, whom he had met in Paris. “I suggested to him,” Jefferson noted, “the enterprise of exploring the Western part of our continent, by passing thro St. Petersburg to Kamchatka, and procuring a passage thence in some of the Russian vessels to Nootka Sound, whence he might make his way across the continent to America.” But Catherine the Great had other ideas on the matter, and it never amounted to anything.[4]Thomas Jefferson, autobiography manuscript, 6 January 1821, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/98-01-02-1756.

Sometime in 1792, Jefferson approached the American Philosophical Society to “set on foot a subscription to engage some competent person to explore . . . by ascending the Missouri, crossing the Stony Mountains, and descending the nearest river to the Pacific.” His timing was fortuitous. For in late 1792 French botanist and explorer André Michaux (1746–1802), who had already spent many years in America, found himself “destitute of means,” unable to get the back pay owed to him as a Member of the French Court, and wondering whether the political upheavals in France left him with a job or not. It seemed to Michaux, unaware as yet of Jefferson’s proposal, that the American Philosophical Society (APS) might be of some service in such matters.[5]See Jefferson to Paul Allen, 18 August 1813, founders.archives.gov/ documents/Jefferson/03-06-02-0341-0002.

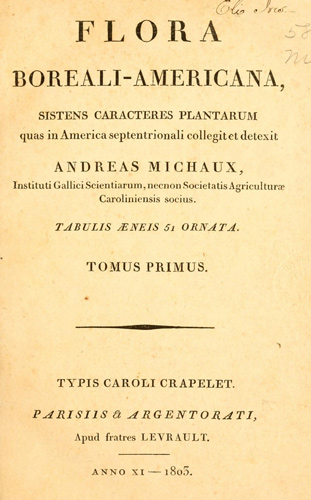

André Michaux (1746–1802)

Written entirely in Latin, the cover of Michaux’s botanical thome translates to:

Flowers of North America, standing characteristics of plants which he collected and discovered in North America. By Andre Michaux, of the French Institute of Sciences, and of the Agricultural Society Carolina member. Fifty-one decorated bronze plates.[6]André Michaux, Flora boreali Americana (Typis Caroli Crapelet: 1803), frontispiece.

Michaux had trained at Buffon’s Jardin du Roi (Royal Botanical Garden) in Paris. Not long after he returned from some natural history work in Persia, in an 18 July 1785, brevet, Louis XVI appointed him Royal Botanist and sent him to America. The position came with an annual salary set at 2000 livres. At least in principle it did. And so on 28 September 1785, André Michaux boarded Le Courrier de New York docked quayside in Lorient, and set sail for the fledgling United States. After forty-six days at sea, much of it on unbearably choppy waters, he arrived in New York harbor.

Michaux spent 1785–1792 botanizing (a favorite term of his) around the United States and Canada, collecting samples of anything and everything, discovering scores of new species, shipping more than 60,000 samples back to France, and eventually publishing two books including, The Flora of North America. During these years he visited Philadelphia on many occasions, but he does not appear to have interacted directly with Jefferson or the American Philosophical Society before December 1792.[7]André Michaux, Histoire des Chênes de l’Amérique, de l’imprimerie de Crapelet (Paris, 1801); Michaux, Flora boreali Americana, Crapelet (Paris, 1805).

By the time André Michaux rode into Philadelphia on 8 December 1792, King Louis XVI was in prison awaiting trial. Michaux no longer knew whether he was acting as a botanical minister for the new French republic or whether he would ever receive the 17,520 livres in back pay that had accumulated over the years, and if not, how he could cover his mounting debts. The idea he came up with was designed both to mitigate his economic woes and allow him to do the botanizing he so loved.

Proposed Expedition

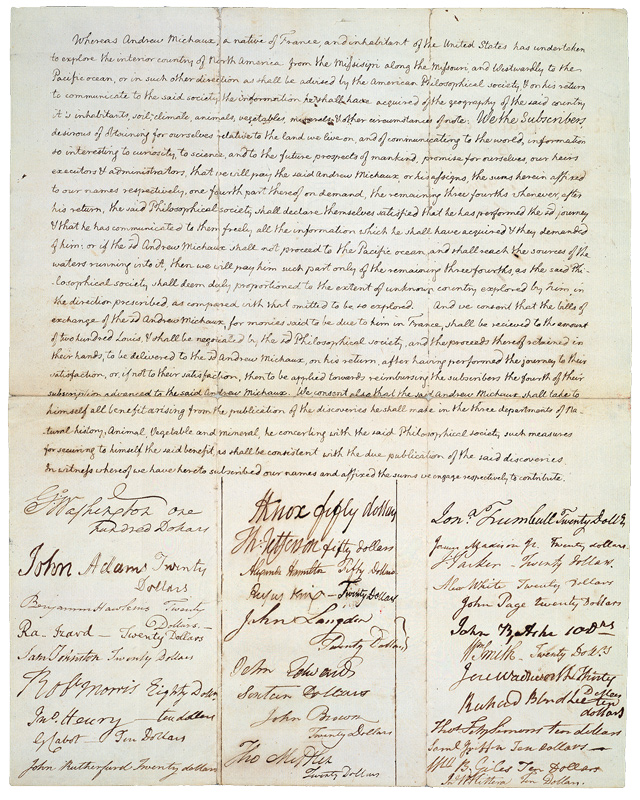

This is the only document signed by four living U.S. presidents: George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison. A fourth column, not shown above lists eight additional signatures for a total of thirty-six sponsors, a third of whom were elected American Philosophical Society members.[8]“Michaux Expedition Subscription List,” American Philosophical Society, /www.amphilsoc.org/item-detail/michaux-expedition-subscription-list-0 accessed 2 December 2022.

On 10 December, Michaux approached members of the American Philosophical Society, including Jefferson, with an audacious idea in which he proposed “the advantages to the United States of having geographical information about the country west of the Mississippi and asked that they back [his] explorations,” informing his potential sponsors that he was “ready to go to the sources of the Missouri and even explore the rivers that flow into the Pacific Ocean.” In short time Jefferson, the Vice President of the Society, as well as Secretary of State, became the point man handling Michaux’s proposal.[9]Michaux journal entry, 10 December 1792, The Diary of André Michaux, Book 2, Missouri Botanical Garden Archives, translated by Mary E. Radford.

Michaux next provided the American Philosophical Society with a list of conditions under which he would undertake the journey, including “letters of recommendation necessary for negotiations with . . . Indian chieftains.” In his Observations on Proposed Western Expedition, presented to the Society on 20 January 1793, Michaux spelled out who would get what, should he head off to the Pacific: “All knowledge, observations, and geographical information will be communicated to the Philosophical Society,” but “other discoveries in natural history will be for my own immediate profit, and, afterwards, destined for the public good.”

The next day, 21 January 1793, though Michaux would not have known it, Louis XVI went to the guillotine. One day after that, Jefferson, on behalf of the American Philosophical Society, presented Michaux with the first official subscription for this expedition. The Society, “desirous of obtaining for ourselves relative to the land we live on, and of communicating to the world, information so interesting to curiosity, to science, and to the future prospects of mankind,” would sponsor the expedition. The subscription was signed by thirty-eight individuals, many of them members of the American Philosophical Society, the first two signatures being those of President Washington and Vice President John Adams, respectively, with commitments of $120, and later down on the list, Secretary of the Treasury Hamilton and Secretary of State Jefferson, pledging $50 each. The total for all signatories came to $870—a respectable start to what would be an ongoing funding campaign.[10]American Philosophical Society Subscription for Michaux’s Expedition, 22 January 1793, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-25-02-0088.

“The chief objects of your journey,” as the American Philosophical Society’s charge to Michaux instructed him, were “to find the shortest and most convenient route of communication between the U.S. & the Pacific Ocean . . . [to] take notice of the country you pass through, its general face, soil, rivers, mountains, its productions animal, vegetable, and mineral so far as they may be new to us and may also be useful or very curious . . . the names, numbers, & dwellings of the inhabitants, and such particularities as you can learn of their history, connection with each other, languages, manners, state of society & of the arts & commerce among them.” A decade later, Lewis and Clark’s instructions were in many ways a longer, more detailed version of those given to Michaux.[11]American Philosophical Society’s Instructions to André Michaux, on or about 30 April 1793, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-25-02-0569. The APS instructions were almost certainly written by Jefferson.

Genêt’s Covert Mission

Edmond Charles Genet (c. 1809)

By Ezra Ames (1768-1836)

Oil on wood panel, 30 3/8 x 23 1/2, bequest of George Clinton Genét, courtesy Albany Institute, downloaded from the Internet Archive.

Everything appeared to be in place for Michaux to begin gathering what he would need for an American expedition the likes of which had never before been attempted. But just then fate, in the person of French Minister Edmond-Charles Genêt, stepped in.

When Genêt, the first official representative of the new French Republic to the United States, arrived in Philadelphia in May of 1793, he and his entourage were greeted cautiously by the Washington administration and warmly by the general public. The reception might have been otherwise had “Citizen” Genêt’s covert mission been known. For above and beyond a generic (and admirable enough) charge to facilitate an alliance that would “encourage the liberation of mankind,” Genêt had been ordered by the leaders of the New Republic to “pave the way for the liberation of Spanish America . . . [and] deliver our brothers in Louisiana from the tyrannical yoke of Spain . . . [which] will be easy to carry out if the Americans wish it.” Genêt was empowered “to make whatever expenditures he shall judge appropriate to facilitate the execution of the project, leaving this to his prudence and loyalty.” These clandestine instructions put him on a collision course with President Washington, who, only a month earlier, had issued a proclamation of neutrality, ordering America to “pursue a conduct friendly and impartial toward the belligerent powers.”[12]F. Turner, Correspondence of the French Ministers to the United States, 1791-1797 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Press, 1904), 201–11.

Genêt had the liberation of both Florida and Louisiana in his sights, but it was the Louisiana mission that would lead him to Michaux. He had done his homework, and knew of the long-standing disputes between the people of Kentucky and the Spanish over navigation rights on the Mississippi River, and thought this might incline Kentuckians to join with the French to free Louisiana. Genêt turned to his well-connected countryman Michaux to facilitate just the sort of political machinations that Washington’s neutrality proclamation had been put in place to prevent.

Michaux met with Genêt twice during the first two weeks the minister was in Philadelphia, and Genêt instructed him to travel to Kentucky to gauge the sentiments of the people there on the question of joining with the French to end Spain’s control of Louisiana. Genêt instructed Michaux to meet with George Rogers Clark about spearheading both a land and amphibious assault on New Orleans, and if Rogers Clark were so inclined, Michaux was to commission him General in what Genêt was calling the Independent and Revolutionary Legion, and provide Rogers Clark with commissions for those he would invite to join him. Michaux had never forgotten that his primary duty in the New World was to serve France, and so he accepted this new charge from the Republic, placing the American Philosophical Society expedition to the far West on hold. He spent most of June preparing for the political journey and set out for Kentucky on 16 July.

By 28 June, Jefferson knew that Michaux was heading to Kentucky, as is evidenced in a letter of introduction the Secretary of State wrote to Isaac Shelby, Governor of Kentucky. At this point, Jefferson was aware that Genêt had sponsored Michaux’s trip, but it appears that he did not yet know the true nature of the expedition, describing Michaux only as “[a] conductor of a botanical establishment belonging to the French nation . . . a man of science and merit . . . [who] goes to Kentucky in pursuit of objects of natural history and botany . . . Mr. Genêt the Minister of France here, having expressed to me his esteem for Mr. Michaux.”[13]Jefferson to Isaac Shelby, 28 June 1793, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-26-02-0359.

Suspicions

Though Jefferson did not pick up on them, there were warning bells that something unusual, something more than a natural history jaunt, was in the works, as when Genêt asked Jefferson to appoint Michaux French Consul to Kentucky, which the Secretary of State refused to do. But after Genêt came to visit him a week later, Jefferson became privy to the sordid details: “Mr. Genêt called on me and read to me very rapidly instructions he had prepared for Michaux who is going to Kentucky,” Jefferson wrote of the meeting, “besides encouraging those inhabitants to insurrection . . . [they would] undertake the expedition against N. Orleans, and then Louisiana, to be established into an independent state connected in commerce with France and the US.” Adding insult to injury, Genêt told Jefferson that “he communicated these things to [him], not as Secy. of State, but as Mr. Jeff.” Jefferson then informed Citizen Genêt that “enticing officers and soldiers from Kentucky to go against Spain, was really putting a halter about their necks, for that they would assuredly be hung if they command hostilities against a nation at peace with the US.”[14]Jefferson’s notes of cabinet meeting and conversations with Edmond Charles Genêt, 5 July 1793, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-26-02-0387.

Yet, despite now knowing what Genêt and Michaux were up to, Jefferson neither stopped the mission nor informed others in the Washington administration about it. We can only speculate on why, but one possibility is that this was all a bit of calculated ambiguity on the Francophile Secretary of State’s part. There was, of course, the matter of neutrality, but at the same time, Jefferson was concerned that the Spanish were itching to provoke a war over Louisiana with the United States. What’s more, any action against Genêt and the French might strengthen his Hamiltonian Federalist opponents who were wary of Genêt from the start and would use a rebuke as evidence they had reason to be. Jefferson’s solution was to warn Genêt of the dangers—people will hang for violating neutrality—but not go so far as to expose the plan to Washington or his cabinet, and force its termination.

In August, as Michaux approached Kentucky, Citizen Genêt was the subject of much discussion in the political circles of Philadelphia. By this time, President Washington had learned of Genêt’s plans for Louisiana and Florida. On 23 August, after consulting with his advisors, Washington sent a request to the French government to recall Genêt. There was no public announcement of the recall request, nor did it leak to the press, and Genêt was not informed until at least September 15, and perhaps a few days later. Genêt was furious at the recall request, but reasoned that such a request might very well be denied by his government. In any case, he saw no reason to have it interfere with Michaux’s mission, and there is no evidence that he informed his botanist-turned-operative of any change to the plans.

Michaux finally arrived in Danville, Kentucky, on September 10—he did quite of bit of botanizing on the way down, considerably slowing his trek south—and met with George Rogers Clark twice during his first two weeks there. Rogers Clark informed him that “I every day meet with encouragement and am anxious for us to commence on our operations,” and that he would be honored to work with France and to accept a position in the Independent and Revolutionary Legion. He made it clear to Michaux that he could provide the troops, but that he needed boats, supplies, and money to achieve the goal of freeing Louisiana from the Spanish. Michaux assured Rogers Clark that he would provide everything needed, but before that he would need to return to Philadelphia to secure resources.[15]George Rogers Clark to Michaux,15 October 1793, in Annual Report of The American Historical Association for the Year 1896 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Press, 1896), 1013.

The Death Knell

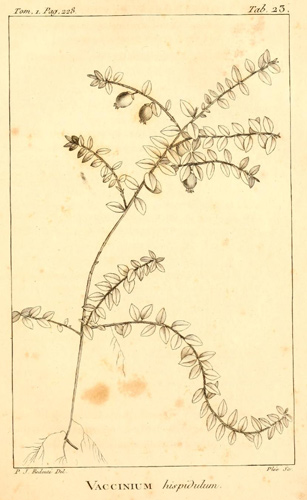

Vaccinium hispidulum

Presently Gaultheria hispidula, creeping snowberry

From Michaux’s Flora of North America, vol 1, plate 23

Michaux’s description of this plant, entirely in Latin, begins: “V. repens, hispidulum: folii sub-rotundo-ovalibus, acuminatis: floribus solitarie axillaribus . . . .” Roughly translated, this becomes, V. creeping, hispidulum: leaves sub-round-oval, pointed: flowers solitary axillary.”[16]Michaux, Flora, 1:228–9. On 13 August 1805, near Pattee Creek in the Lemhi River valley, Lewis collected a specimen of common snowberry. A few seeds were taken back to Bernard McMahon in Philadelphia who planted them.

Arriving back in Philadelphia on 12 December—again, he took his time, botanizing along the way—Michaux met with Genêt. In a letter to Rogers Clark two weeks later he informed him that Genêt fully supported his plan and was working to obtain the resources needed, but “the difficulty, or rather impossibility, to [effect] a diversion with the navy forces the Minister to delay the operations until next Spring.” That delay was a death knell for the mission, for just a week after Michaux’s letter to Rogers Clark, Genêt learned that he was no longer acting as a representative of the French government. Washington’s recall request had at last arrived in France in October, and three days later, the Committee of Public Safety heeded Washington’s request and ordered that Genêt be recalled. News of that decision reached Philadelphia in January of 1794 and quickly became common knowledge. On 10 January, Michaux noted in his journal that he “returned to Minister Genêt the warrants he had entrusted to me for General Clark . . . I told him I wanted to use my time for research in natural history as much as possible.” The mission to use French and American forces to free Louisiana from Spanish control was over.[17]Michaux to Rogers Clark, 27 December 1793, in Annual Report of The American Historical Association for the Year 1896, 1024. Fearing the guillotine on his return to France, Genêt asked for, and was … Continue reading

Michaux’s desire to employ his “time for research in natural history as much as possible” would not translate into reviving any journey to the Pacific. Though there was no formal decision to scrap the project, once the “Genêt Affair,” as it has come to be known, had reached its dénouement, all things Citizen Genêt were politically and socially toxic, and the American Philosophical Society understood it would not be proper for Michaux to be first to explore the far West. Michaux too had likely had enough. He had grown weary of others’ managing his life, be they the American Philosophical Society or Genêt. He wanted his freedom back so he could botanize to his heart’s content, which is precisely what he did until he eventually sailed back to France two and a half years later.

Notes

| ↑1 | This article is from Lee Alan Dugatkin, “André Michaux’s ‘Almost Expedition’ to the West in 1793,” We Proceeded On, Vol. 47 No. 1, January, 2022, 5–11. The original article is available at our sister site, lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol47no1.pdf#page=7 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | “Hermon Atkins MacNeil,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hermon_Atkins_MacNeil accessed on 9 February 2021. |

| ↑3 | Jefferson to George Rogers Clark, 4 December 1783, founders. archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-06-02-0289; George Rogers Clark to Jefferson, 8 February 1784, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-15-02-0587. |

| ↑4 | Thomas Jefferson, autobiography manuscript, 6 January 1821, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/98-01-02-1756. |

| ↑5 | See Jefferson to Paul Allen, 18 August 1813, founders.archives.gov/ documents/Jefferson/03-06-02-0341-0002. |

| ↑6 | André Michaux, Flora boreali Americana (Typis Caroli Crapelet: 1803), frontispiece. |

| ↑7 | André Michaux, Histoire des Chênes de l’Amérique, de l’imprimerie de Crapelet (Paris, 1801); Michaux, Flora boreali Americana, Crapelet (Paris, 1805). |

| ↑8 | “Michaux Expedition Subscription List,” American Philosophical Society, /www.amphilsoc.org/item-detail/michaux-expedition-subscription-list-0 accessed 2 December 2022. |

| ↑9 | Michaux journal entry, 10 December 1792, The Diary of André Michaux, Book 2, Missouri Botanical Garden Archives, translated by Mary E. Radford. |

| ↑10 | American Philosophical Society Subscription for Michaux’s Expedition, 22 January 1793, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-25-02-0088. |

| ↑11 | American Philosophical Society’s Instructions to André Michaux, on or about 30 April 1793, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-25-02-0569. |

| ↑12 | F. Turner, Correspondence of the French Ministers to the United States, 1791-1797 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Press, 1904), 201–11. |

| ↑13 | Jefferson to Isaac Shelby, 28 June 1793, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-26-02-0359. |

| ↑14 | Jefferson’s notes of cabinet meeting and conversations with Edmond Charles Genêt, 5 July 1793, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-26-02-0387. |

| ↑15 | George Rogers Clark to Michaux,15 October 1793, in Annual Report of The American Historical Association for the Year 1896 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Press, 1896), 1013. |

| ↑16 | Michaux, Flora, 1:228–9. |

| ↑17 | Michaux to Rogers Clark, 27 December 1793, in Annual Report of The American Historical Association for the Year 1896, 1024. Fearing the guillotine on his return to France, Genêt asked for, and was granted, asylum to remain in the United States. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.