An American Expansion

President Thomas Jefferson wrote to a fellow scientist in late January 1804, that “I confess I look to the duplication of area for extending a government so free and economical as ours, as a great achievement to the mass of happiness which is to ensue.” Just nine months earlier the President’s representatives in Paris had bargained successfully with Napoleon’s bureaucrats not only to buy the port of New Orleans, then the keystone of the continent, but also to acquire, at three cents an acre, an area extending from the Mississippi River to . . . where? No one knew until Meriwether Lewis stood at the crest of the Rocky Mountains at a place known today as Lemhi Pass, on 12 August 1805.

Expansion of the American experiment created wonderful opportunities for the nation and daunting challenges for Jefferson and his circle. In the late summer of 1804, Lewis and Clark named the three rivers they deemed the sources of the Missouri River in honor of the team at the pinnacle of contemporary American statesmanship: the President himself, Secretary of State James Madison, and of the Treasury Albert Gallatin.

Gallatin’s frugality and financial acumen made possible payment to France. Moreover, he pointed out that since the Constitution did not specifically deny the President authority to make the purchase, the transaction would be legal. Ever since then, the “doctrine of implied powers” has been a key element in presidential policy around the world.

Madison faced an unhappy Spain because that government had been assured by the French that it would never alienate Louisiana—nor throw the Roman Catholic creole population of New Orleans into the prison of American protestantism. He also coped with Napoleon’s on-again, off-again attitude regarding the sale. Most importantly, he had been the President’s confidant and support in the long planning stages.

President Jefferson was one of those western-looking aristocrats who believed that the United States should people all America. Also, he was well aware that France, Spain, and Britain also had designs on the land, people and resources west of his own republic. When his representatives, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, set out to trace the lineaments of the Missouri River, their objective would be the debouchure of the river already named by an American explorer-trader for the popular symbol of American empire—Columbia.

With the purchase of Louisiana, the nest of nationhood would extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Rocky Mountains, but Liberty’s Rainbow arched from sea to shining sea.

Paris Negotiations

Timeline

11 April 1803

- Secretary of State James Madison has authorized Livingston to pay up to 50 million francs ($9,375,000) for New Orleans. When Talleyrand asks how much the U.S. would pay for the entire territory of Louisiana, Livingston offers 20 million francs.

- François Barbé-Marbois’s counter: 100 million francs plus the liquidation of claims against France for American citizens’ property seized by French ships during the naval “war” of 1798-99.

- Livingston declines.

- Barbé-Marbois: 60 million francs, plus assumption of claims.

- Livingston and Monroe: 40 million francs.

- Barbé-Marbois: no sale.

- Livingston and Monroe: 50 million francs.

- Barbé-Marbois: 60 million francs.

27 April 1803

- Agreed: The price is 60 million francs ($11,250,000), plus 20 million francs ($3,750,000) to cover American citizens’ claims.

30 April 1804

- Signed and sealed. Barbé-Marbois has gotten a better price than Napoleon had expected.

Spain, France, and England had now and then regarded the youthful republic as a potential ally, or at least a quiet neutral. President Jefferson had worked to establish a foreign policy that would play them against one another and reflect the position he had set forth so succinctly in his first inaugural address: “We see no enemies at home or abroad; we spend little to protect ourselves and we mind our own business.”

Madison directed foreign policy along pacific lines also, and Gallatin had minded business so well that the country enjoyed good credit, a bit of budget surplus, and excellent connections with major bankers at home and abroad.

Easter week in Paris, 1803, was truly momentous for the young United States of America. The American Minister to France, Robert R. Livingston, was deep in negotiations—initiated by direct command of the First Consul, Napoleon Bonaparte[1]In post-revolutionary France, the maelstrom of domestic intrigue and international strife resulted a series of new governments, including, in 1795, a five-man executive committee called the … Continue reading—to discuss the difficult question of New Orleans, the Mississippi and Franco-American relations. A springtime warmth suffused the international atmosphere.

Livingston had been sent to Paris, in Jefferson’s words, because “the cession of Louisiana and the Floridas by Spain to France works most sorely on the United States.” Spain had held the territory since the end of the Seven Years War (1756-63), or the French and Indian War, as Americans termed it. In secret moves culminating in the Treaty of San Idelfonso, France had reclaimed the area in 1800, but left Spanish officials in charge. For a time, Spain had allowed unfettered commercial traffic on the lower Mississippi River, but royal pique toward both the U.S. and France had led to an abrupt, threatening closure of the river: New Orleans was no longer open to American ships, and Americans west of the Alleghenies were landlocked. Jefferson immediately dispatched his Virginia protégé, James Monroe, to Paris to reinforce Livingston. Monroe arrived at Le Havre on Good Friday 1803. On Easter Sunday Napoleon, 100 miles away in Paris, learned of his arrival by semaphore.[2]Semaphore was a long-distance visual telegraph system invented and named by Claude Chappe in 1794, during the French Revolution. A similar system, developed in 1795 in England, was used in the U.S. … Continue reading

Napoleon possessed an agile mind, imperial demeanor, and an enormous need for money. If the sale of a territory he already considered to be American could bring in some ready cash, why not sell it? These thoughts crystallized at High Mass on that Easter Sunday. Completing his worship, he called for his minister of the treasury, Marquis François Barbé-Marbois (barb-mar-bwah). Marbois had served in the U.S. and married an American woman, and was a good friend of Jefferson, partly because of his friendships in the United States.

Napoleon made it clear that he wanted to sell the whole of Louisiana to the Americans. “They only ask of me one town in Louisiana, but I consider the colony as entirely lost.” He was referring to the ongoing American settlement in the Mississippi valley; to his devastating losses in his attempt to reinstate slavery in Haiti; to the might of the British navy, which controlled access to the New World; and to Jefferson’s wish to purchase at least a small piece of land near New Orleans where goods coming down the Mississippi could be deposited for transfer to seagoing ships.

At midnight, 13 April, Livingston sent a dispatch to Madison: “I have just come from the Minister of the Treasury [Marbois]. Our conversation was so important, that I think it necessary to write it.” Livingston and Monroe committed their country to pay France sixty million francs for the Louisiana Territory and twenty million to settle claims American merchants and shippers had lodged against France after the short, bitter naval near-war of 1799. The Mississippi, New Orleans, the vast lands west of the river and the Gulf Coast eastward[3]This was a misunderstanding. The French had no claim to most of the eastern Gulf Coast, nor Florida. During Monroe’s presidency, Spain was persuaded, partly by General Andrew Jackson’s … Continue reading were going to be American. Livingston concluded his dispatch: “every moment is precious.”

Indeed it was. Negotiations between the Americans and the French went on for a month; they would have taken at least three months had Livingston and Monroe taken the time to communicate with Washington, D.C. Just a few weeks after that business was concluded, war again erupted between France and England. Old Europe continued to tear itself apart. The American people had taken a giant step toward realizing a cherished dream.

Official Documents

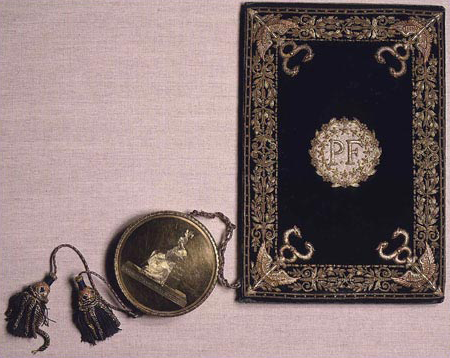

Three documents were transmitted detailing the sale and purchase of Louisiana. Each is covered with purple velvet embroidered with silver and gold thread and white silk appliqué. The initials in the center stand for “Peuple Francais”—The People of France. The object attached by the braided cord, called a skippet, contains the seal of the French government impressed in wax.

The treaty of cession is written both in French and English on both sides of three sheets and one side of a fourth, measuring 9-5/8 inches by 14-3/8 inches. Article I declares, in part:

The First Consul of the French Republic desiring to give to the United States a strong proof of his friendship doth hereby cede to the United States in the name of the French Republic for ever and in full Sovereignty the said territory with all its rights and appurtenances as fully and in the Same manner as they have been acquired by the French Republic.

The convention, or international agreement, for payment is written on both sides of one sheet and one side of a second. Article I states:

The Government of the United States engages to pay to the French Government in the manner Specified in the following article the sum of Sixty millions of francs independent of the Sum which Shall be fixed by another Convention for the payment of the debts due by France to citizens of the United States.

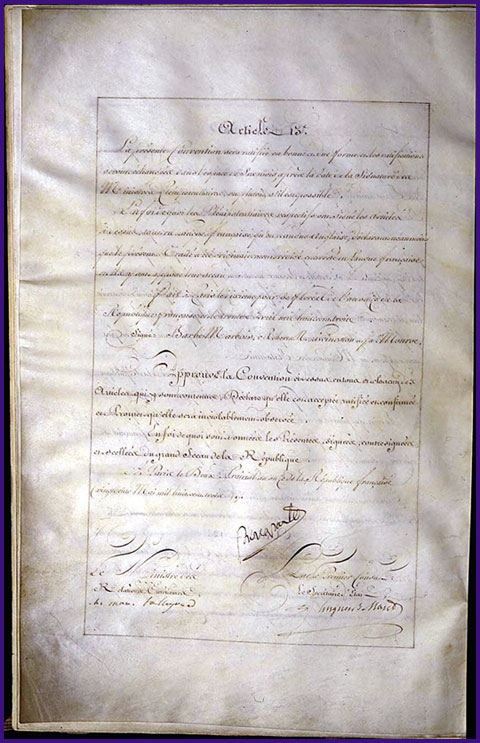

The claims convention, pictured above and on the next page, is written on both sides of three sheets. Article I reads:

The debts due by France to citizens of the United States contracted before the 8th Vendémiaire[4]The first month of the calendar inaugurated in 1792 by the short-lived First French Republic. In the Gregorian calendar, used elsewhere throughout Europe and North America, Vendémiaire extended from … Continue reading ninth year of the French Republic/30th September 1800/ Shall be paid according to the following regulations with interest at Six per Cent; to commence from the period when the accounts and vouchers were presented to the French Government.

All three document are signed by Robert Livingston, James Monroe, François Barbé-Marbois, and Bonaparte.

Article 13 Transcript

The present convention Shall be ratified in good and due form and the ratifications Shall be exchanged in Six months from the date of the Signature of the Ministers Plenipotentiary, or Sooner if possible.

In faith of which, the respective Ministers Plenipotentiary have signed the above Articles both in the French and English languages, declaring nevertheless that the present treaty has been originally agreed on and written in the french language, to which they have hereunto affixed their Seals.

Done at Paris, the tenth of Floreal, eleventh year of the French Republic. 30th April 1803.

[Signatures]

Louisiana’s Negotiators

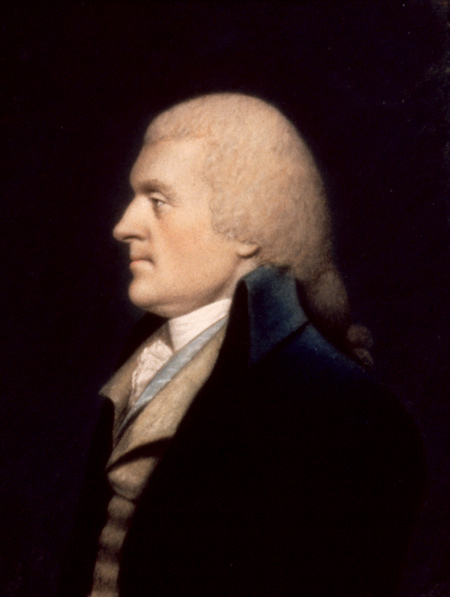

Thomas Jefferson

A Virginian active in revolutionary movements and governor during the Revolutionary War, Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) wrote and styled the Declaration of Independence. He was an Enlightenment philosopher, Francophile, and served in a number of high offices before becoming the third president of the United States in 1801. As part of a strategic effort to ensure national control of Mississippi valley, he launched several military expeditions, the most important of which was that of Lewis and Clark. With James Madison, he guided the process which led to the acquisition of Louisiana Territory.

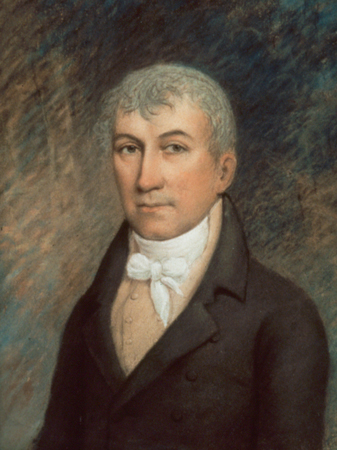

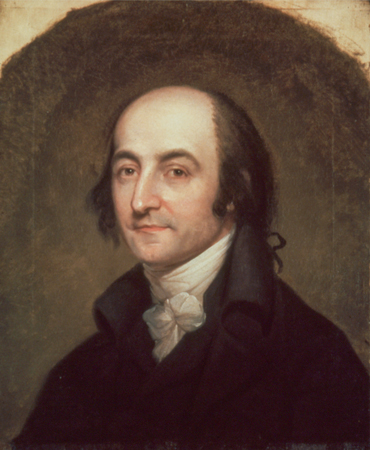

Rufus King

Rufus King (1755-1827) was an important Massachusetts merchant-financier and served as minister to Court of St. James. With his remarkable ability to acquire influential British friends, he served as a conduit of important British intelligence. After relocating to New York for business reasons, he was elected to several terms as Senator from New York. His advice and information were crucial for President Jefferson and Secretary of State James Madison during the Louisiana acquisition.

Robert Livingston

Robert Livingston (1746-1813), scion of the largest landholding family in New York, was baronial in appearance and in action. He was a member of the committee drafting the Declaration of Independence, but was prevented from signing it when he hastened back to New York to help write that state’s first revolutionary constitution. He became Chancellor in the new state government and in that capacity administered the oath of office to President George Washington. He moved away from the reigning Federalist party and was appointed minister to France in 1801 by President Jefferson. He bombarded Napoleon’s court with papers arguing for American presence on Mississippi and, with James Monroe, negotiated the Louisiana Purchase. He supported new agricultural and transportation technologies including the first steamboat on Hudson River.

James Madison

James Madison

by Catherine Drinker (1841-1922)

of a portrait by Gilbert Stuart

Independence National Historical Park.

James Madison, Jr. (1751-1836) was a Virginian, classics and theological scholar, member of the Committee of Public Safety during the revolution, and served as delegate to the Continental Congress that wrote the Articles of Confederation. He noted the weaknesses of federated systems and worked successfully for the Constitutional Convention where his influential voice structured the system of government for the new nation. He served as foreign minister and was appointed Secretary of State by Thomas Jefferson. He succeeded Thomas Jefferson as President of the United States and led the country through the War of 1812. His proven record of support for free navigation on the Mississippi served the country well during the crisis preceding the sale of the Louisiana Territory to the United States.

James Monroe

James Monroe

copy by James Sharples (1751–1811)

of a portrait by Thomas Sully (1783–1872)

Independence National Historical Park.

Youngest of the Virginia statesmen, James Monroe (1758-1831) served in the revolutionary war, studied law with Thomas Jefferson, and from early in his career identified with United States control of Mississippi valley. As an expansionist advocate, he was sent to France to calm western fears that President Jefferson might not push hard enough for a solution to the Louisiana problem. His administration as the fifth President of the United States (1817-25) was called the Era of Good Feeling. In his presidential message of 2 December 1823, he set forth the Monroe Doctrine, which declared that the Western Hemisphere was thenceforth strictly an American zone of influence: European colonizers and adventurers were no longer welcome.

Albert Gallatin

Born in Switzerland, Abraham Alfonse Albert Gallatin (1761-1849) emigrated to the United States at age 19. He became a key figure in the implementation of Jefferson’s unprecedented design for a new and growing republic. As Jefferson’s Secretary of the Treasury, he engineered the financial details of the Louisiana Purchase (without increasing taxes), then resolved the constitutional issues that complicated the transaction. Throughout his sixty-year-long career he worked sedulously in behalf of free public education, universal suffrage, and the abolition of slavery.

François Barbé-Marbois

François Barbé-Marbois

by Jean François Boisselat (1835)

WikiCommons accessed on 30 May 2018.

François Barbé-Marbois, marquis de Barbé-Marbois (1745-1837) was French consul, early revolutionary, friend of Thomas Jefferson and other important Americans, and belonged to Napoleon’s inner circle. As minister of the French public treasury, he negotiated directly with Livingston and Monroe on price, conditions, and the description of the Louisiana Territory. He survived Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo, and served under two succeeding French monarchs. He wrote an account of the Louisiana Purchase, which was published in 1821.

Joseph Bonaparte

Joseph Bonaparte

by François Gérard (c. 1808)

Musée national du Château de Fontainebleau.

Born Giuseppe di Buonaparte, Joseph-Napoléon Bonaparte (1768-1844) was brother of Napoleon I. As the next oldest brother, he felt himself entitled to consideration as heir to the crown. Employed as an occasional diplomat, he concluded the 1800 treaty of cooperation with between France and the United States at Morfontaine. He was King of Naples briefly, and after that country fell under French rule, he became King of Spain. He argued against continuation of European conflict by urging his older brother to acquire and maintain an overseas empire, which would include Louisiana. Too weak to be successful in any serious endeavor, he took refuge in the United States after his brother’s final exile to St. Helena.

Lucien Bonaparte

Lucien Bonaparte

by François-Xavier Fabre (after 1800)

WikiCommons accessed on 30 May 2018.

Born in Corsica as Luciano Buonaparte, Lucien Bonaparte (1775-1840) was the fiery brother of Napoleon I, active in revolutionary circles and influential with that portion of the French public. He was a proverbial thorn in Napoleon’s side: always argumentative, at odds with prevailing policy, and determinedly difficult. His espousal of colonial views may well have alienated his oldest brother from that scheme. Opposed to his oldest brother’s intention to declare himself Emperor of the French Republic, he went into self-exile initially in Italy, and then in Britain. He returned to France after Napoleon’s abdication in 1814.

Manuel de Godoy

Manuel de Godoy

by Agustin Esteve y Marqués (1800–08)

Art Institute of Chicago.

Manuel Godoy y Álvarez de Faria (1767-1851), 1st Duke of Alcudia, was later named—some thought ironically—Prince of Peace. He gained this title because he brokered peace between Spain and France at Basel in 1795. Clever and self-assured, he was a match for Tallyrand and Napoleon. He sought to block the retrocession of Louisiana Territory, or at least to gain some significant advantage from it.

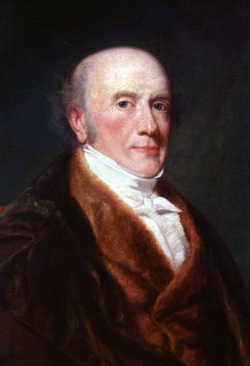

Pierre César Labouchere

Pierre César Labouchere

Alexander Baring

by George Peter Alexander Healy (1842)

New York Historical Society.

Pierre César Labouchere (1772-1839) and his British brother-in-law, Alexander Baring, were the major banking figures in the negotiations leading to the Louisiana Purchase and to subsequent American payments to European bondholders as the debt was redeemed. Labouchere was the son of Huguenot French parents then living in The Hague. He trained in the cloth business in Nantes at age 13 and moved to Amsterdam in 1789 to apprentice to the Scottish founded, Dutch merchant banking firm of Henry Hope and Company. Within five years, during the turbulent times of the French Revolution and occupation of Holland, he became a full partner in the firm. As conditions warranted, he lived in London or Amsterdam, conducting business diligently wherever he was. As the Peace of Amiens came to an end during the Louisiana Purchase negotiations, Alexander Baring was forced to return to England and Labouchere finalized arrangements for the Purchase.

Labouchere retired to England upon a magnificent estate, well stocked with the art of Dutch Masters, his success founded upon probity and square dealing. His views on financial honesty were well known: “I wish that the House [of Hope & Co.] might always have as its motto: ‘Honour and Profit.’ But if either of these must be erased, I would that it be the latter.”

Napoleon I

Napoleon standing in his Study in the Tulleries

by Jacques-Louis David (1812)

National Gallery of Art.

Born Napoleone Buonaparte, Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821) was the son of a Corsican official and revolutionary. Sent to France as a young teenager to become army officer and gifted in mathematics, he chose to serve in the artillery. He welcomed revolution and was employed by various factions to control opposition. He became a member of the ruling elite and eventually First Consul in 1798. He directed armies through a successful northern Italian campaign and prepared to acquire French hegemony in Europe. After dallying with the idea of developing an overseas empire, he decided his naval resources were inadequate. Because he was land-oriented, he decided to sell his new Louisiana acquisition. Whether he did this in order to wean the United States away from its Anglophilia, or to gain a possible ally against England, or simply because he needed immediate cash to prosecute a new war against a British-led coalition is impossible to know.

Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périogord

Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périogord

by François Gérard (1808)

Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périogord (1754-1838) descended from an old and noble family and was the victim of a childhood accident that crippled him. Because some careers were closed to him, he was groomed for the Church and became Bishop and ultimately a moderate revolutionary. Clever and corrupt, he is often described as “glabrous.” Napoleon distrusted and perhaps feared him, but employed him because of his talents. During a sojourn in the United States caused by The Terror in France, Talleyrand developed disdain for the rustics who had successfully engineered their own break from England. He soon became persona non grata because of his role in the X, Y, Z affair and his later demand for a bribe to broker the Louisiana negotiations. Although he gained and lost power periodically, he was consistent in his wish to cement a Franco-British alliance. His views supported the neo-colonial arguments of Joseph and Lucien Bonaparte, and had he gotten his way, Louisiana would have remained French.

Financing the Purchase

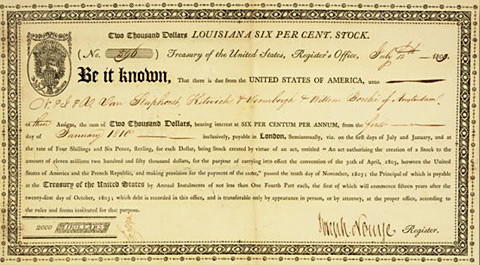

Certificates of Public Debt

Stock Certificate

(Original dimensions, 10.5 by 5.5 inches.)

Two Thousand Dollars LOUISIANA SIX PER CENT. STOCK.

(No. 596) Treasury of the United States, Register’s Office,

July 12th—1809.

National Archives and Records Administration.

Transcript:

Be it known, That there is due from the UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, unto,

N. & J. & R. van Staphorst, Ketwich & Voombergh & William Borski of Amsterdam,

or their Assigns, the sum of Two Thousand Dollars, bearing interest at SIX PER CENTUM PER ANNUM, from the first day of January 1810 inclusively, payable in London, Semiannually, viz. on the first days of July and January, and at the rate of Four Shillings and Six Pence, sterling, for each Dollar, being Stock created by virtue of an act, entitled “An Act authoring the creation of a Stock to the amount of eleven millions two hundred and fifty thousand dollars, for the purpose of carrying into effect the convention of the 30th of April, 1803, between the United States of America and the French Republic, and making provision for the payment of the same,” passed the tenth day of November 1803; the Principal of which is payable at the Treasury of the United States by Annual Instalments[sic] of not less than One Fourth Part each, the first of which will commence fifteen years after the twenty-first day of October 1803; which debt is recorded in this office, and is transferable only by appearance in person, or by attorney, at the proper office, according to the rules and forms instituted for that purpose.

For a brief period from October 1801, through the middle of May 1803, Napoleonic France and the Great Britain of George III shared an uneasy peace. Mutual mistrust fed an appetite for building up armies and navies. Expenditures in turn fueled a great need for hard cash. The French had wasted thousands of men and vast sums trying to re-shackle the recently freed slave population in Haiti. That old imperial dream died hard. Napoleon needed cash to prepare for the looming war with England and her continental allies. His decision to sell not just the city of New Orleans and a duty-free port to Americans, but to convey the whole Louisiana Territory to the new democracy, was part of his strategy to raise funds for a new war and perhaps to acquire an ally. There were many uncertainties in the air—Napoleon was besieged by those who wished to restore the old colonial empire, or who wished him to renege on his promise to sell the Louisiana Territory.

President Jefferson and Albert Gallatin faced the challenge of delivering enough money to Paris to satisfy the First Consul’s appetite, and to do it promptly. They issued certificates of public debt, or stocks.[5]Noah Webster, in his Compendious Dictionary of the English Language (published in 1806), defined a stock as ‘property or interest in a joint capital or fund,’ and bond as simply ‘an … Continue reading Stocks would be sold in various denominations at six percent. However, no French banking house would serve as intermediary in the transaction, for fear of British blockade and seizure. Marbois turned to the London-based merchant bankers, the House of Baring. It was a well known Anglo-American firm with strong ties to a major continental house and would be acceptable to all parties.[6]The House of Baring had a long, close connection with the government of the United States. Following World War II it evolved into an investment bank with global interests. In a spectacular example of … Continue reading Sir Francis Baring, scion of the house, in turn relied upon his son-in-law Pierre Cesar Labouchere, a partner not only in Baring but also in the prestigious Hope and Company of Amsterdam. The Dutch conduit would make prompt payment in Paris possible. Alexander, Sir Francis’ second son, would handle the American end of the deal. Alexander had married Anne Louisa, the daughter of Henry Bingham, the richest man in America. The two younger men worked out the details. It was a tidy family arrangement. Strikingly, it was not a major challenge for these veteran financiers. Both had worked in this entangled international money market for some time.

Thus it was that a London banking firm sold American stocks on an international market to help France finance a renewed war with Great Britain.

Complications

Notice that the stock certificate is dated 12 July 1809, six years after the Louisiana Purchase Treaty was signed. In late spring of l803 both France and England were preparing to renew hostilities. Barings Bank, founded in London in 1762, was given the task of selling the majority of the stocks to fund the purchase. As hostilities spread and France occupied Holland, major partners in Hope and Company removed to London also. Napoleon was aware that capital was critical to his war effort and so he gave assurances that Hope and Company would be free to conduct business without duress if they would return to Amsterdam. The stocks there however were already sold and Dutch investors were invited to purchase any available in London. It would appear that the stock certificate illustrated here was likely purchased with a special sinking fund, amounting to perhaps $178,000, which was established by some of the more important Dutch investors—whose sons also owned land in the Hyde Park area of upstate New York.

The U.S.Treasury sent $11,250,000 in stocks to the French ministry of finance. The remainder of the $15 million purchase price would be set aside to pay American merchants’ claims against France. Livingston and Monroe had pledged an advance of $2 million to be channeled through a Philadelphia banking firm, Willing and Francis. Baring bought a third of those stocks. Eventually all funds would pass through Barings. Every major player was happy: Napoleon bought arms; we doubled our territory; Great Britain controlled this financial pipeline and enhanced her national wealth.

Consider how a nation just emerged from its revolutionary fatigues could acquire such an increase in security and territory, and how it could pay for it right after another war largely fought on its own soil. The United States operated on a shoestring financially, but paid its way in an increasingly complex world of finance, and proved its worth. Gallatin’s prudent budget administration meant that no additional taxes had to be levied upon citizens to pay off the stocks. Interest, and later redemption, payments came from selling public lands.

Baring and Sons Profit

In late November 1803, the Spanish Governor of Louisiana presented a representative of the French government with a silver platter holding keys to important public buildings in New Orleans. (It was a comic-opera scene, of course; Spain had retroceded Louisiana to France three years before.)

A few weeks later, the Frenchman handed the same silver platter and keys to an American official. When Lewis and Clark crossed the Mississippi from Camp River Dubois on 14 May 1804, and started up the Missouri River, they entered a land that had been delivered on a silver platter.

Baring and Sons might have smiled at the irony. They, in turn, had found a pot of gold. It is estimated that after all the stocks were retired and all payments made, their company profited to the tune of $3 million. At the appointed time the United States began repaying the loan—which, including interest, came to around $20,000,000.

And Marbois had gotten a better price for Louisiana than Napoleon expected!

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Plan a trip related to The Louisiana Purchase:

Notes

| ↑1 | In post-revolutionary France, the maelstrom of domestic intrigue and international strife resulted a series of new governments, including, in 1795, a five-man executive committee called the Directory. Four years later, on 10 November 1799, the Directory was overthrown and replaced by three Consuls—administrators. From their first meeting Bonaparte assumed the leading role. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Semaphore was a long-distance visual telegraph system invented and named by Claude Chappe in 1794, during the French Revolution. A similar system, developed in 1795 in England, was used in the U.S. until electric telegraphy was introduced by Samuel F. B. Morse in 1837. |

| ↑3 | This was a misunderstanding. The French had no claim to most of the eastern Gulf Coast, nor Florida. During Monroe’s presidency, Spain was persuaded, partly by General Andrew Jackson’s soldiers, to cede all of Florida to the United States. |

| ↑4 | The first month of the calendar inaugurated in 1792 by the short-lived First French Republic. In the Gregorian calendar, used elsewhere throughout Europe and North America, Vendémiaire extended from September 22nd or 23rd to October 21st or 22nd, depending on the year. |

| ↑5 | Noah Webster, in his Compendious Dictionary of the English Language (published in 1806), defined a stock as ‘property or interest in a joint capital or fund,’ and bond as simply ‘an obligation.’ In his later (1828) American Dictionary of the English Language, he more specifically defined stock as ‘money lent to a government, or property in a public debt; a share or shares of a national or other public debt,’ whereas a bond was ‘an obligation or deed by which a person binds himself, his heirs, executors, and administrators, to pay a certain sum, on or before a future day appointed.’ Today a bond is a public or governmental debt, while a stock is an investment in a private corporation. |

| ↑6 | The House of Baring had a long, close connection with the government of the United States. Following World War II it evolved into an investment bank with global interests. In a spectacular example of organizational dysfunction, a rogue trader, Nick Leeson, who was considered a rising young star bet 1.4 billion dolars on derivatives based upon the Japanese stock market. An earthquake in Kobe had rattled that market and Leeson bet on the Osaka stock exchange that the Nikkei index would rise. He leveraged too much and lost his bets, which led to the bankruptcy of this venerable old merchant banking house. |