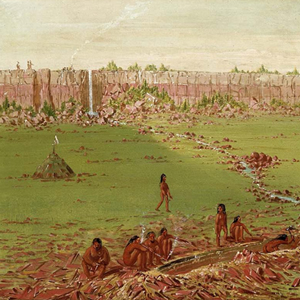

“The Osages are so tall and robust as almost to warrant the application of the term gigantic: few of them appear to be under six feet, and many are above it. Their shoulders and visages are broad, which tend to strengthen the idea of their being giants.”

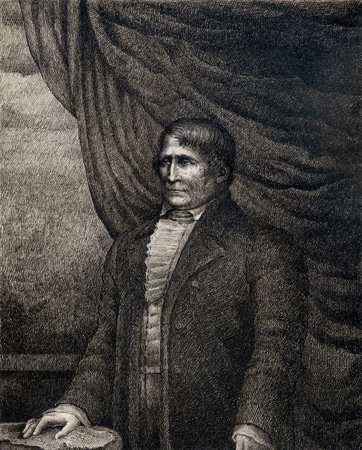

The First Delegation

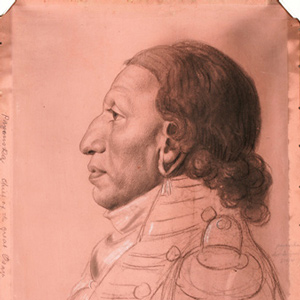

Osage Delegation Member

by Charles B. J. F. de Saint Mémin (1770–1852)

Watercolor by Charles Balthazar Julien Févrét de Saint-Mémin based on a physiognotraced likeness by the same artist. Washington, D.C., 1807. Actual size: 7½ x 6¾

Courtesy Winterthur Museum, Winterthur, Delaware. Accession No. 54.19.3.

This painting is believed to be one of at least five small watercolors commissioned from Saint-Mémin by a British diplomat, Sir Augustus John Foster, who was in Washington from 1804 to 1807. All were copies of portraits Saint-Mémin had previously drawn with the aid of a physiognotrace.[2]William E. Foley and Charles David Rice, “Visiting the President: An Exercise in Jeffersonian Indian Diplomacy,” The American West, Vol. 16, No. 6 (November-December 1979), 6.

Victor Tixier provides the following description:

The man’s eyelids, cheeks, and torso are painted orange-red. His eyebrows and facial hair have not been shaved but plucked, as has the hair on his head, except for the crest, or roach, which has also been dyed with vermilion (powdered cinnabar mineral), while the queue down his back retains its natural color. His headdress, colored blue-green with verdigris (ver-dih-gree), features the head of a small raptor and several waterfowl beaks, as well as hummingbird skins. At his ear is a tuft of swan’s down dyed with powdered cinnabar. The black scarf and breast-band may be intended to suggest his respect for Anglo formality. His metal armband, perhaps a gift from his hosts, is engraved with the figure of an eagle holding the seal of the United States.[3]John Francis McDermott, editor, and Albert J. Salvan, translator, Tixier’s Travels on the Osage Prairies, 1844 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1940), 136-37.

They were “certainly the most gigantic men we have ever seen,” Thomas Jefferson wrote to Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin on 12 July 1804. A dozen Osage men and two boys, the first of three Indian delegations to visit Mr. Jefferson during his two administrations, had arrived in Washington City the previous day, escorted by Peter Chouteau, a prominent St. Louis fur traders and the government’s first agent to the Osages. On the 13th the President wrote to Secretary of the Navy Robert Smith, “They are the finest men we have ever seen. They have not yet learnt the use of spiritous liquors.”[4]Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1783-1854, 2d ed., 2 vols. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:199-200. The celebration of their … Continue reading Pursuant to Jefferson’s explicit orders, Lewis had arranged their trip to Washington City through Chouteau before leaving St. Louis. Upon their arrival in Washington City, the President addressed them with earnest expressions of friendship and cooperation: “We are all now of one family, born in the same land, & bound to live as brothers.” Stressing the motives of “commerce & useful intercourse,” he announced, “You have furs and peltries which we want, and we have clothes and other useful things which you want. Let us employ ourselves then in mutually accommodating each other.”[5]Ibid., 1:201. In October, after touring Baltimore, New York, and Philadelphia, the Osages returned to their homes at the Place-of-the-Many-Swans beyond the Ozarks in the valley of the Osage River.

It must have been a satisfying experience for Jefferson; he seemed to be achieving the goal he had set for his administration. “The truth is,” he had written to Secretary of the Navy Smith on 13 July 1804, “they are the great nation South of the Missouri, . . . as the Sioux are great North of that river. With these two powerful nations we must stand well, because in their quarter we are miserably weak.”[6]Ibid., 1:200n.

The Second Delegation

The second Indian delegation, with Captain Amos Stoddard in charge, consisted of chiefs from twelve tribes living along the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers, left St. Louis in October 1805 and returned the following summer.[7]Captain Stoddard had accepted the transfer of Louisiana Territory at St. Louis on behalf of the United States, then served as the interim military and civil commandant in charge of the Louisiana … Continue reading Among this group, much to the distress of their hosts, were a few who were excessively fond of whiskey; one chief died, apparently from an overdose. Moreover, Stoddard’s budget was wrecked by the Indians’ appetites for beef—up to 12 pounds per man per day. On the other hand, in Boston the Osage Chief Tatschaga delivered an ardent testimonial with profound effect before the Massachusetts Senate: “Our complexions differ from yours, but our hearts are the same colour, and you ought to love us for we are the original and true Americans.”[8]Foley and Rice, 12.

Victor Tixier left a description in his journal that helps us imagine the sound of the visitors’ oratory:

The Osage language is poor in nouns but rich in endings which modify or change their meanings. Therefore, according to what the traders say, it is very difficult to speak it well. One of the interpreters has assured me that Mr. Ed. Chouteau was the only white man who spoke it like an Osage. It is . . . sung, so to speak, and the slow delivery of each syllable will give the word a great force of expression. An adjective is put to the superlative by lengthening its last syllable. . . . The pronunciation is soft, and guttural sounds are made almost harmonious.[9]McDermott and Salvan, 148.

Jefferson, in his speech to the second Indian delegation, on 4 January 1806, told the assemblage he had sent “our beloved man Capt. Lewis one of my own family” to talk with all the Indian nations along the Missouri. Upon his return Lewis would ultimately “inform us in what way we could be useful to them.” The new “factory” system of trading, he assured the Osage chiefs, would not be profit-driven. They would buy American goods at cost, and receive for their furs and pelts “whatever we can get for them again.”

“My children,”[10]That salutation, which is apt to strike the twenty-first-century reader as belittling and insulting, was merely a counterpart of contemporary Anglo-American forms of address: The comparatively bland … Continue reading Jefferson continued in a firmer tone, “we are strong, we are numerous as the stars in the heavens, & we are all gun-men. Yet we live in peace with all nations; and all nations esteem & honour us because we are peaceable & just.”[11]Jackson, Letters, 281-82. The Osage chief who delivered the delegation’s response did not mince any words:

Fathers: Meditate what you say, you tell us that your children of this side of the Mississippi hear your Word, you are Mistaken, Since every day they Rise their tomahawks Over our heads, but we believe it be Contrary to your orders & inclination, & that, before long, should they be deaf to your voice, you will chastise them. . . .

You say that you are as numerous as the stars in the skies, & as strong as numerous. So much the better, fathers, tho’, if you are so, we will see you ere long punishing all the wicked Red skins that you’ll find amongst us, & you may tell to your white Children on our lands, to follow your orders, & to do not as they please, for they do not keep your word. Our Brothers who Came here before told us you had ordered good things to be done & sent to our villages, but we have not seen nothing. . . .

We are Conscious that we must speak the truth, truth must be spoken to the ears of our fathers, & our fathers must open their ears to truth to get in.[12]Ibid., 1:285-87.

All too soon, American justice would prove to be simply racist, and its peaceableness a hollow promise. The Osages could see it coming.

The Third Delegation

The third group of Indian representatives to visit the President consisted of the Mandan chief, Sheheke (Big White), and his family, who accompanied Lewis and Clark from their Knife River village to St. Louis, on to Virginia and thence to Washington City. At the same time, Pierre Chouteau led six Osage chiefs direct from St. Louis to Washington, and later conducted all the Indians back to St. Louis. In the summer of 1807, belligerent Arikara warriors on the middle Missouri blocked the first attempt, to return Sheheke to his home. The second effort, in 1809, required a major military force to fulfill the obligation (see Sheheke’s Delegation).

Since early colonial times Indian visitors and tribal emissaries had been welcomed formally in the Eastern seats of government and culture. By 1800 the purposes and protocols for such events were essentially formalized, while the objectives—beyond satisfying public curiosity about the “savages”—the official intention to impress them with the white man’s numbers, wealth, military power, and organized urbanity had begun to backfire among the native nations. To the extent that Indian visitors were impressed by what they saw, they were reviled in equal measure by their own people when they returned home. Finally, Jefferson’s determination to keep government spending to a minimum compelled him, following the fiasco of the third delegation’s visit, to suspend the practice for the duration of his administration.

Cross-purposes

Meanwhile, in August 1808 General Clark oversaw the establishment of Fort Osage, the first trading post in his western plan, near today’s Sibly, Missouri. Principally, it would facilitate trade between the U.S.and the Osages, Otoes, and their friends, and also ensure them of the protection of the U.S. Army from the tribes that the government had encouraged to move west of the Mississippi, as well as from the truculent Sioux. At virtually the same moment, however, the persistence of internecine warfare between the Osages and their neighbors had led Governor Lewis to announce that the Osage nation was no longer under the protection of the United States, and that the Shawnees, Lenape Delawares, Kickapoos, Sioux, Sauks, and others were free to settle their differences with the Osages in their own way, provided they would do so “with sufficient force to destroy or drive them from our neighborhood.”[13]Lewis to William Henry Harrison, July 1808, cited in Jackson, Letters, 2:626n. In the captains’ “Estimate of the Eastern Indians“–meaning east of the Rockies–Lewis wrote, … Continue reading The governor’s ire heated to a full boil. He declared to Secretary of War Henry Dearborn that the Osages had “cast off all allegiance to the United States,” and that war appeared inevitable. “I have taken the last measures for peace,” he declared. Dearborn was out of town when the letter arrived at the War Department, so it was forwarded to the President, who immediately reminded Lewis that “commerce is the great engine by which we are to coerce them, & not war.”[14]Meriwether Lewis to Henry Dearborn, 1 July 1808, and Thomas Jefferson to Meriwether Lewis, 21 August 1808, both in Territorial Papers, 14:196-98, 220. Cited in Landon Y. Jones, William Clark and the … Continue reading Might the President not have sensed that his “beloved man,” who was to die by his own hand within another three months, was already feeling mortal hopelessness eating at his heart and soul?

Worse yet, Jefferson’s plan to reserve Louisiana for the Indian nations had already begun to dissolve in frustration, despair, and racial antagonism on the part of all parties concerned. By 1819 the Osages were refusing to make the hundred-plus-mile trip from the Marais des Cygnes (“Marsh of the Swans”) to the trading center Clark had built for them on the Missouri. A military presence was no longer needed to protect the Osages, so the army was permanently withdrawn from the Fort. By 1822 the trading house was closed. In 1825 the factor, George Sibley, was reassigned to lay out a road from Fort Osage to New Mexico—the Santa Fe Trail—and Americans’ ambitions followed a different road for a while.

More of the Story

- February 18, 1804 -

From Wood River, Lewis works with St. Louis fur trader Pierre Chouteau to send a delegation of Osage to Washington City. In a letter, Lewis encourages Chouteau to take the group himself.

- February 20, 1804 -

Based on his letter of 18 February, Lewis likely follows through on his promise to join Clark in St. Louis today. There, he helps Pierre Chouteau organize an Osage delegation bound for Washington City.

- April 21, 1804 -

Across the Mississippi, a cannon is heard and soon after 22 Osage Indians arrive escorted by trader Pierre Chouteau. The captains accompany the delegation to St. Louis leaving Sgt. Ordway in charge.

- May 3, 1804 -

From St. Louis and Camp River Dubois, Lewis and Clark write letters of introduction for Pierre Chouteau who will soon take a delegation of Osage to Washington City. Trader Manuel Lisa visits Clark.

- July 11, 1804 -

The boats make six miles up the Missouri before camping on an island at the mouth of the Big Nemaha River in present Nebraska. Clark finds a stray horse, and in Washington City, an Osage delegation arrives.

- July 12, 1804 -

The expedition takes a day at the Big Nemaha River to rest and wash clothes. Pvt. Willard is tried and found guilty of sleeping while on guard duty. His sentence is "One hundred lashes on his bear back".

- July 16, 1804 -

The expedition sails twenty miles up the Missouri River and camps near a ‘Bald Pated’ prairie at the Nishnabotna River. In Washington City, President Jefferson addresses a visiting Osage delegation.

- July 18, 1804 -

Clark remarks on the region’s geology and Lewis collects a partridge pea specimen as they travel up the Missouri below present Nebraska City. At their evening camp, a stray Indian dog is fed.

- August 21, 1804 -

As the battle strong winds heading up the Missouri, trader Pierre Dorion informs the captains about the Big Sioux country including their red pipestone quarry. They camp near present Ponca, Nebraska.

- November 5, 1804 -

The day is spent raising Fort Mandan cabins and splitting boards for the cabin lofts. Mandan hunters report capturing 100 pronghorns, Clark's rheumatism continues, and Lewis spends the day writing.

- June 13, 1805 -

At the Grand Fall, Lewis marvels at the "sublimely grand specticle". Downriver, Clark gives Sacagawea a dose of salts. At Fort Massac, General Wilkinson has questions about the people sent to him in the barge.

- June 25, 1805 -

Below the Falls of the Missouri, Clark enjoys a cup of coffee. At the upper camp, Drouillard and Frazer bring in 800 pounds of dried meat and in Washington City, Jefferson shares news of the Expedition.

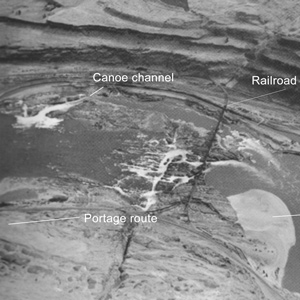

- October 22, 1805 -

The expedition arrives at the Falls of the Columbia. With the help of some Wishram villagers, they portage their baggage along the northern shore. Others scout the channel that the canoes will navigate.

- January 4, 1806 -

Sgt. Gass and Pvt. Shannon travel through the marshes and dunes of the Clatsop Plain on their way to the salt makers' camp. At Fort Clatsop, Lewis describes Clatsop views on material goods.

- January 11, 1806 -

At Fort Clatsop, careless paddlers fail to secure the Chinookan canoe, and it floats away. After visiting Kathlamets leave to barter with the Clatsops, Lewis describes the Columbia River trade network.

- April 30, 1806 -

The expedition sets out on the Travois Road passing through sagebrush and sand dunes. They camp on the Touchet River north of present Walla Walla. Lewis describes eating dog, river otter, and horse.

- May 9, 1806 -

The corps moves about six miles to Twisted Hair‘s small camp near present Nezperce, Idaho. The horses and saddles left with the Nez Perce last fall are found, and then, it begins to snow.