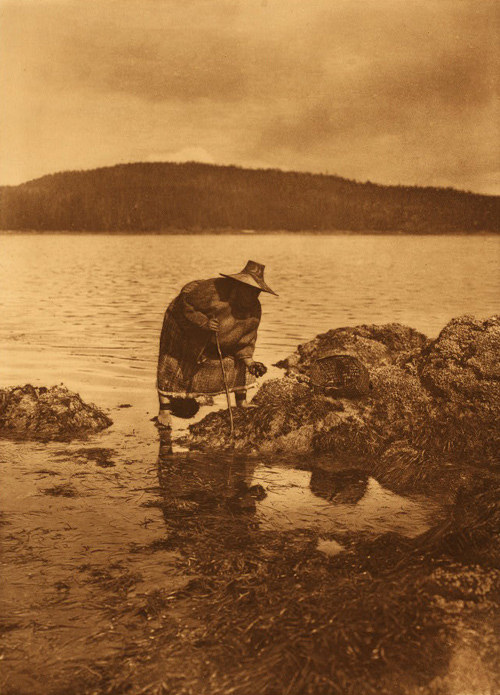

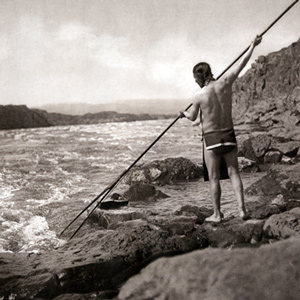

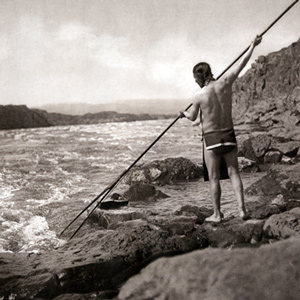

Gathering Abalones – Nakoaktok

Edward S. Curtis (1868–1952)

Northwestern University Library, Edward S. Curtis’s “The North American Indian,” 2003.[1]Edward S. Curtis, The North American Indian (1907-1930) v.10, The Kwakiutl. ([Cambridge: The University Press], 1915), plate no. 342.

Languages of the Chinookan group were spoken from the Pacific Coast to the lower end of the Columbia Gorge. On the coast, Lower Chinookan speakers spread from Willapa Bay (north of present Long Beach, Washington, the expedition’s farthest northern reach along the coast) through the Chinooks proper, and south to the Clatsop people on the Columbia’s south side.

The border between Lower Chinookan and Upper Chinookan languages was about the eastern end of the Columbia Estuary in 1805. There, as Clark took vocabularies from the The Wahkiakums, he noted that their language differed from those spoken upstream. The Wahkiakums shared the Kathlamet tongue with their neighbors on the Columbia’s south side, the Kathlamets proper. This language is generally grouped with Upper Chinookan, but some linguists designate Kathlamat (which some label Middle Chinookan) as a third full branch of the Chinookan family.

Upper Chinookan languages were used along both sides of the Columbia River. Now almost all extinct, they included dialects of the Cascades, Clackamas, White Salmon, and the Wishrams and Wascos at The Dalles. Their upper extent was, in fact, there at The Dalles, where the Sahaptian-speaking Nez Perce traveling with the Corps announced that they could no longer be helpful as translators.

Related Pages

Lewis and Clark appear to have been unaware of the existence of Chinook Trade Jargon. Never-the-less, some of the words they encountered would be later documented as part of the jargon.

Chinookan Woven Hats

by Mary Malloy

Today five hats at the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology (PMAE) at Harvard University have a provenance that potentially associates them with the Lewis and Clark expedition. These hats represent an extensive network of trade.

The Wascos and Wishrams

by Barbara Fifer

At The Dalles lived Upper Chinookan people, the Wishrams on the Columbia’s north (Washington) side—and their allies the Wascos on the south (Oregon) side—who were the main masters of the regional trading center. The Lewis and Clark Expedition encamped on the north side.

The Kathlamets

by Kristopher K. Townsend

The expedition journalists recorded several encounters with the Kathlamets, or Cathlamets, during their stay at the Pacific coast during the 1805–06 winter. On 11 November 1805, while hunkered down in a “dismal nitch” on the north side of the Columbia, a canoe “loaded with fish of Salmon Spes. Called Red Charr” pulled to shore. After buying 13 sockeye, Clark marveled.

The Skilloots

by Kristopher K. Townsend

The Skilloot were an Upper Chinookan group that spoke the Clackamas dialect of the Chinookan language. They were located on both sides of the Columbia River above and below the mouth of the Cowlitz. At first, the captains applied the name over a much wider area, perhaps misinterpreting a similar expression meaning ‘look at him!’. Cape Horn, a few miles east of Washougal, was named sqúlips, and could be the origin of the tribe’s name.

Wind Mountain was at the western extent of a series of Upper Chinookan villages called by Lewis and Clark the “Chilluckkittequaw nation.” Apparently, when asked for a tribal name, the captains were given the word for ‘he pointed at me’. Chilluckittequaw was adopted as their name a century later by early ethnographer Frederick Hodge. Between Wind Mountain and Hood River, nine villages have been identified, some overlapping with Klickitats

The Watlalas

by Kristopher K. Townsend

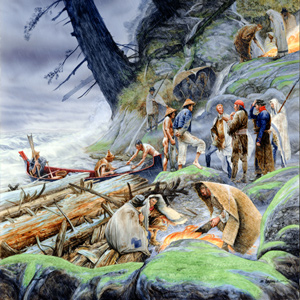

Watlala was the name of a key Upper Chinookan village at the Cascades of the Columbia. The name has been extended by many to mean the tribe more often called the Cascades. The captains called them the Shahala, meaning ‘those upriver.’ The natural constriction of the river provided the people with a fishery and a good measure of control over those who traveled up and down the river. As a result, the Cascade Clahclellah village which the expedition visited on 31 October 1805 and 9 April 1806 was a major trade center before and during white contact.

The Clatsops

by Kristopher K. Townsend

The creek where Coyote built his legendary house—today’s Neacoxie Creek—flows north to south bisecting nearly the length of the Clatsop Plain. A village at the estuary created by the ocean, Neacoxie Creek and the larger Necanicum River is Ne-ah-coxie Village. Nearby were three other Clatsop villages, and for a short time, a salt works built by soldiers from the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

The Multnomahs

by Kristopher K. Townsend

When interviewing William Clark and George Shannon to prepare his condensation of the expedition journals, Nicholas Biddle wrote in his notes that “The Multnomah nation is placed on the Wappatoe Island opposite the mouth of the Multh. river and the inlet which forms the island. . . . the neighbors speak of the Multnomah nations as great &c.”

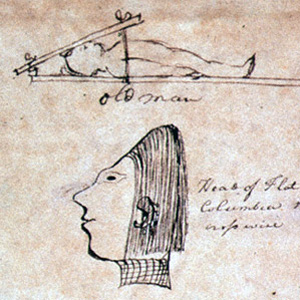

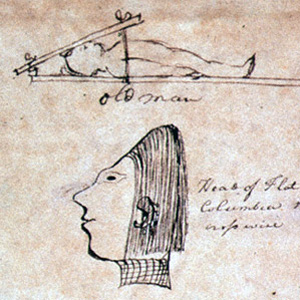

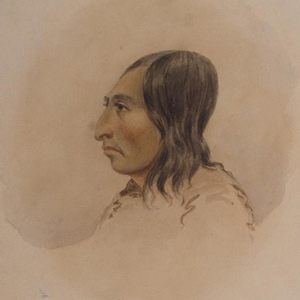

The most remarkable trait in the Clatsop Indian physiognomy, Lewis wrote on 19 March 1806, was the flatness and width of their foreheads, which they artificially created by compressing the heads of their infants, particularly girls, between two boards.

The Chinooks

by Kristopher K. Townsend

Today, Chinook often refers to the politically united Lower Chinook, Clatsops, Willapas, Wahkiakums, and Kathlamets. To Lewis and Clark, the Chinook were the people living on the north side of the Columbia River’s estuary. When Lewis and Clark met them, the people of Baker Bay had been trading with European ships for more than a decade.

The Clackamases

by Kristopher K. Townsend

The Clackamas people had about twelve villages south of the Columbia River, along the Clackamas River, and at Willamette Falls in what is now Portland and Oregon City. They spoke the Clackamas dialect as did nearby Multnomahs and Skilloots. On 2 April 1806, two young Clackamas men came to “Provision Camp” near present-day Washougal and sketched a map of the Willamette River, the mouth of which the expedition captains had failed to find.

The Wahkiakums

by Kristopher K. Townsend

The Wahkiakums exemplify the complexities encountered when trying to classify Chinookan peoples. Linguistically, they spoke the Upper Chinookan Clackamas dialect. Culturally, they were related to the Lower Chinookan Clatsops and Chinooks proper. They resided primarily along the north side of the Columbia between Grays Bay and Cathlamet, Washington.

Life’s Cycle at the Dalles

by Barbara Fifer

From the Columbia Plateau to the river’s mouth, people followed a yearly cycle for fishing, hunting, and harvesting wild foods. In the summer, people from many Sahaptin and Chinookan tribes visited The Dalles to trade and socialize.

Sgt. Gass reported, “We found our huts smoked; there being no chimneys in them except in the officers’ rooms.” Coastal Natives had devised simple, reliable ways of manipulating the balance of atmospheric pressure, temperature and air flow in what is now called the “stack effect.”

Notes

| ↑1 | Edward S. Curtis, The North American Indian (1907-1930) v.10, The Kwakiutl. ([Cambridge: The University Press], 1915), plate no. 342. |

|---|

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.