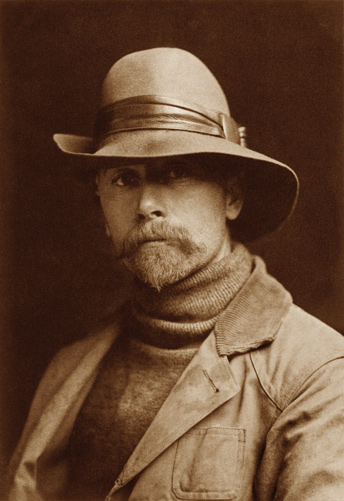

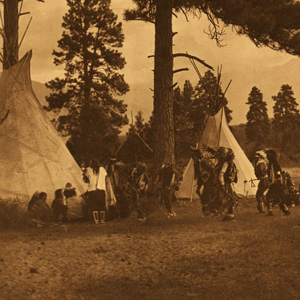

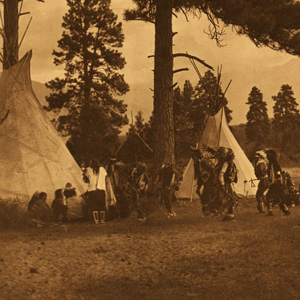

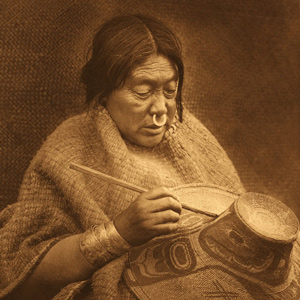

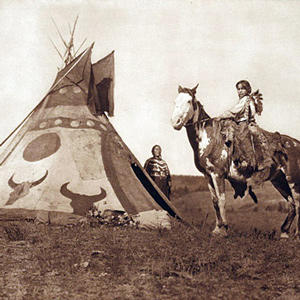

The monumental collection of photographs by Edward Curtis was intended to be the ultimate documentation of the then-apparent end of traditional Indian life-ways. Published between 1907 and 1930, The North American Indian consisted of twenty volumes of illustrated narrative plus twenty portfolios containing over 700 large photogravures. The consummation of thirty years’ work, it was enabled by substantial patronage from the wealthy financier J. P. Morgan.

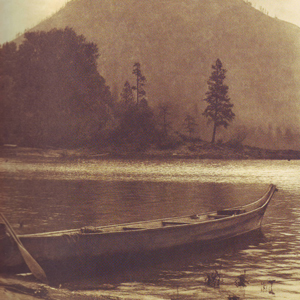

Until the advent of four-color photography in 1935, most photographs were printed in continuous shades of black and white, called grayscale. Edward S. Curtis (1868–1952) developed his photographs using a paper treated with a sepia-toned emulsion. Sepia was a rich brown pigment made from the inky secretion of the cuttle-fish genus, sepia. In the printing of a negative on paper coated with sepia, a chemical reaction converted metallic silver to a sulphide, which resists fading that otherwise would occur with the passage of time. Optically, moreover, the sepia-toned image appears to have a more readily visible range of shadows and highlights than a grayscale image. Historically, it melded the principle of lithography with the spontaniety of photography.

Photogravure is a photomechanical intaglio printing process in which the image to be printed, such as a photograph, is chemically etched into the surface of the printing plate through a screen consisting of tiny square cells (corresponding, electronically, to pixels today). The varying amount of ink held in contiguous squares of different depths produced subtle degrees of density in the printed image. The photogravure process entered the popular press weekly during the first half of the 20th century with the rotogravure, a term which came to denote a section of a newspaper printed on special paper by the photogravure process with a cylindrical, or “rotary,” press, in sepia monochrome. With this step, the lithograph was replaced as a pleasing and economical print medium. (The rotogravure was immortalized by songwriter Irving Berlin in 1915 in “The Easter Parade”—”the photographer will snap us, and you’ll find that you’re in the rotogravure.”) Around 1910, however, photogravures were still printed from flat plates on a letterpress—a slow and expensive process reserved for the finest artistic efforts.

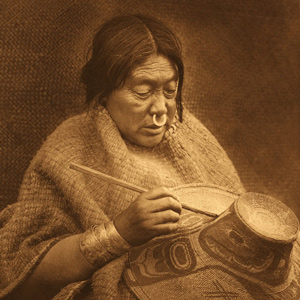

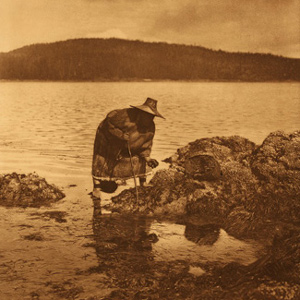

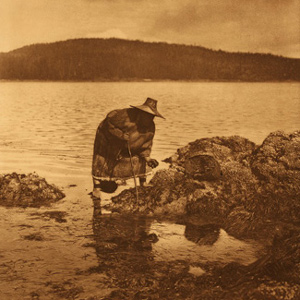

Curtis describes his photographic process in Drying Salmon.

Featured Photographs

June 4, 1806

Seeking guides and diplomats

Lewis fails to secure Nez Perce guides to accompany him to the Falls of the Missouri. Clark seeks Nez Perce guides to accompany him to the Yellowstone River and to parley with the Shoshones.

March 24, 1806

Stolen canoe claimed

On their way to present Aldrich Point, they cross shallow waters crowded with islands, and a Kathlamet man guides them to the correct channel. The guide claims he is the owner of one of their canoes.

September 5, 1805

Flathead Salish council

At present Ross’ Hole, Montana, a council with the Flathead Salish is held using five different languages: Salish-Shoshone–Hidatsa–French–English. Gifts are exchanged, and then horse-trading commences.

April 1, 1806

Exploring the 'Quicksand' River

At Provision Camp, Pryor’s detachment explores the Quicksand River—the present Sandy in Oregon. Visiting Indians of various Nations warn of no food upriver, and no salmon for another month.

November 21, 1805

Clatsop and Chehalis visitors

At Station Camp near the mouth of the Columbia, some Clatsops and Lower Chehalis visit, and the wife of Chinook chief Delashelwilt brings six young females to camp. Clark describes Chinookan woven hats.

March 8, 1805

Rocky Mountain Indians

Greasy Head, a Hidatsa, and an Arikara man inform Clark about the Rocky Mountain Indians They also tell of the rescue of a kidnapped daughter.

October 23, 1805

Lining Horseshoe Bend

The men line the heavy dugout canoes down the Horseshoe Bend of Celilo Falls while Lewis trades their smallest dugout, a hatchet, and a few trinkets for a Chinook-style canoe. Clark shoots at a sea otter.

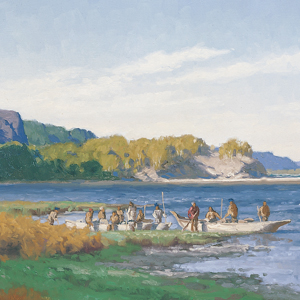

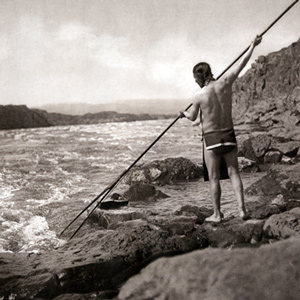

As documented by Edward Curtis

Photographer Edward Curtis himself described the processes pictured here. “In the preparation of this article of food the salmon was beheaded and gutted, and with a sharp knife the two halves were separated from the backbone and the skin.”

September 25, 1805

Searching for a canoe camp

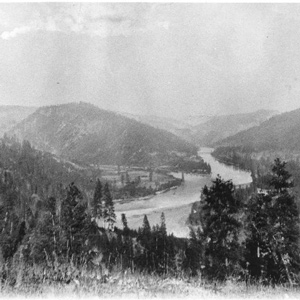

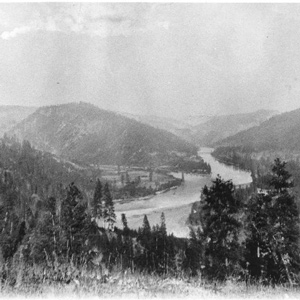

Clark and three Nez Perce travel down the Clearwater River searching for a canoe camp. Clark finds the ponderosa pine trees they need opposite the North Fork Clearwater River in present Orofino, Idaho.

February 21, 1805

Mandan Medicine Stone

At Fort Mandan, Big White and Big Man tell Clark that several Mandan men left the Knife River Villages to consult their Medicine Stone. Lewis’s hunting party returns with about 3,000 pounds of meat.

January 10, 1806

Šax̣awaq̀ap visits

After an early start at the salt makers’ camp, Clark hikes and canoes well into the dark to return to Fort Clatsop. During the day, a dozen Kathlamets visit Lewis and elk become scarce.

May 4, 1806

Crossing the Snake River

With help from their 1805 Nez Perce guide, the Corps crosses the Snake River and continues upriver to present Clarkston, Washington. Curious villagers crowd camp, and Lewis sees menstrual lodges.

October 17, 1805

Snake and Columbia observations

At the confluence of the Columbia and Snake rivers, Lewis takes vocabularies from the Wanapum and Yakama speakers, and hunters are sent out to collect sage grouse specimens. Clark explores the Yakama River.

February 23, 1806

Sea otters and seals

At Fort Clatsop near present Astoria, Oregon, several enlisted men are sick, and Sgt. Ordway writes that he may have influenza. Lewis describes sea otters and seals.

Here the Columbia was “an agitated gut Swelling, boiling & whirling in every direction.” Even so, Cruzatte and Clark agreed that they could run the canoes through.

March 25, 1806

Downstreamer Chinooks

As they paddle along the south shore of the Columbia, the expedition sees Downstreamer Chinooks trolling for sturgeon. After fifteen miles, they find a popular camping spot at the present Clatskanie River.

Chinookan Woven Hats

by Mary Malloy

Today five hats at the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology (PMAE) at Harvard University have a provenance that potentially associates them with the Lewis and Clark expedition. These hats represent an extensive network of trade.

The Umatillas

After emerging from the Wallula Gap on 19 October 1805, Clark came across some Umatillas hiding in their lodges, and he committed a serious faux pas by entering without permission.

November 10, 1804

Hewing and guttering

At Fort Mandan, cottonwood logs are shaped with axes and adzes so that they can be used to cover cabin roofs. A Mandan-Arikara man and his wife cross the river in a bull boat with a load of buffalo meat.

March 19, 1806

Chinookan lifeways

At Fort Clatsop, the captains give Coboway a certificate for his good conduct and describe Chinookan lifeways including manner of dress, decorations, and how they flatten their foreheads.

October 11, 1805

Down the Snake River

Between present Clarkston and Almota, Washington, the paddlers navigate numerous Snake River rapids where the Nez Perce and Palouse have established fisheries. The captains notice a curious sweat lodge.

Homeward bound in April 1806, the Lewis and Clark Expedition traveled through the Columbia Gorge and pitched camps on its north side. Their passage was tense and unpleasant, with Indians taking small goods regularly.

October 6, 1804

Empty Arikara village

The expedition comes to a recently inhabited Arikara village. Walking the shore, Lewis observes several types of birds while the boats struggle to navigate the numerous Missouri River channels.

Beginning with the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, the U.S. government set the vast area north of the Missouri (approximately 20 million acres) aside as the “Blackfeet Hunting Ground” for the Blackfeet and other tribes—Cree, Assiniboine, Gros Ventre, and Sioux.

October 28, 1805

Columbia River headwinds

The expedition sets out from Fort Rock but is soon stopped by headwinds. The captains visit nearby Chilluckittequaws where Clark sees goods acquired from British trade ships and superior Chinookan canoes.

January 16, 1806

Chinookan fishing methods

At Fort Clatsop, the rain and high wind continues. The captains contemplate their ample supply of elk—with a little salt—and they appreciate their dry huts. Lewis describes Chinookan fishing methods.

February 1, 1806

Ammunition inspection

At Fort Clatsop, the lead canisters are unsealed, and the gunpowder they hold is found to be safe and dry. Elsewhere, Zebulon M. Pike reaches what he thinks is the source of the Mississippi River.

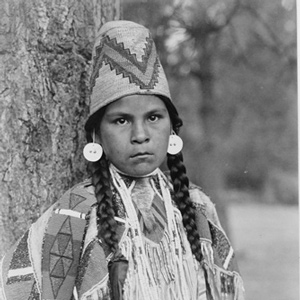

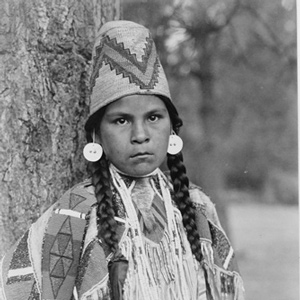

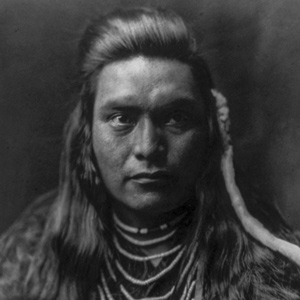

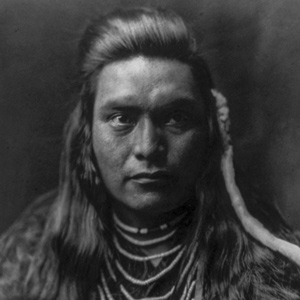

May 13, 1806

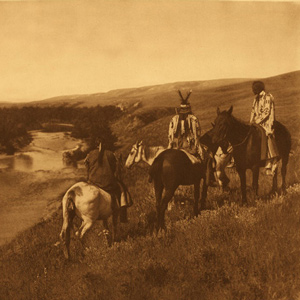

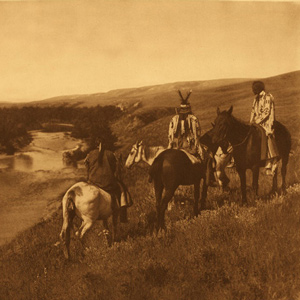

Nez Perce manner and dress

The expedition moves a few miles to the Clearwater River in present Kamiah, Idaho. Lewis describes in detail the appearance, dress, ornamentation, and hairstyles of the Nez Perce.

September 2, 1806

Stopping to hunt

Delayed by wind, Clark pulls in below the James River in present South Dakota, and bison hunting consumes most of the day. Their Indian delegates see their first turkeys and find them impressive.

October 29, 1805

Friendly villages

Moving 35 miles down the Columbia, the expedition encounters many Sahaptin and Upper Chinook villages. They pass an island with numerous graves—Memaloose—and camp above the Little White Salmon River.

April 13, 1806

New dugouts and dogs

With only four dangerously overloaded canoes, Lewis must buy two new dugouts from some Watlalas. He also buys some dogs for dinner at present Dog Mountain east of Stevenson, Washington.

April 20, 1806

Six stolen tomahawks

Working at separate villages at Celilo Falls, the captains have difficulty buying more horses and even lose one. After six tomahawks are stolen, Lewis orders all Indians away from his camp.

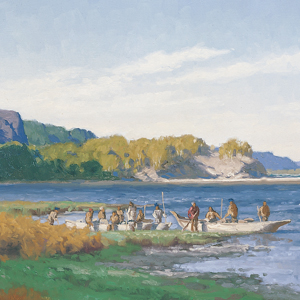

Life’s Cycle at the Dalles

by Barbara Fifer

From the Columbia Plateau to the river’s mouth, people followed a yearly cycle for fishing, hunting, and harvesting wild foods. In the summer, people from many Sahaptin and Chinookan tribes visited The Dalles to trade and socialize.

March 13, 1806

Looking for canoes

At Fort Clatsop, George Drouillard is sent out to buy two canoes from the Clatsops. Enlisted men are sent out to hunt, retrieve elk meat, or find a lost dugout canoe. Lewis discusses coastal fish species.

January 3, 1805

A safe refuge

A Hidatsa man comes for his wife who is seeking refuge at Fort Mandan, and hunters return with a white-tailed jackrabbit. Charbonneau and one enlisted man arrive late at one of the Hidatsa villages.

The Wascos and Wishrams

by Barbara Fifer

At The Dalles lived Upper Chinookan people, the Wishrams on the Columbia’s north (Washington) side—and their allies the Wascos on the south (Oregon) side—who were the main masters of the regional trading center. The Lewis and Clark Expedition encamped on the north side.

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.